I have sustained a steady attraction to the ghostly figures and vibrant textures of her work, the mystery surrounding them has a very personal feel to it and this anticipated presence of the viewer, an open invitation to contemplation, is something I relish.

As I arrive and greet Caroline Minar and Josefina Pierucci, the duo managing the gallery who welcomed the Manila-born artist a year ago as their second permanently represented artist, Coson heartily starts to show me around.

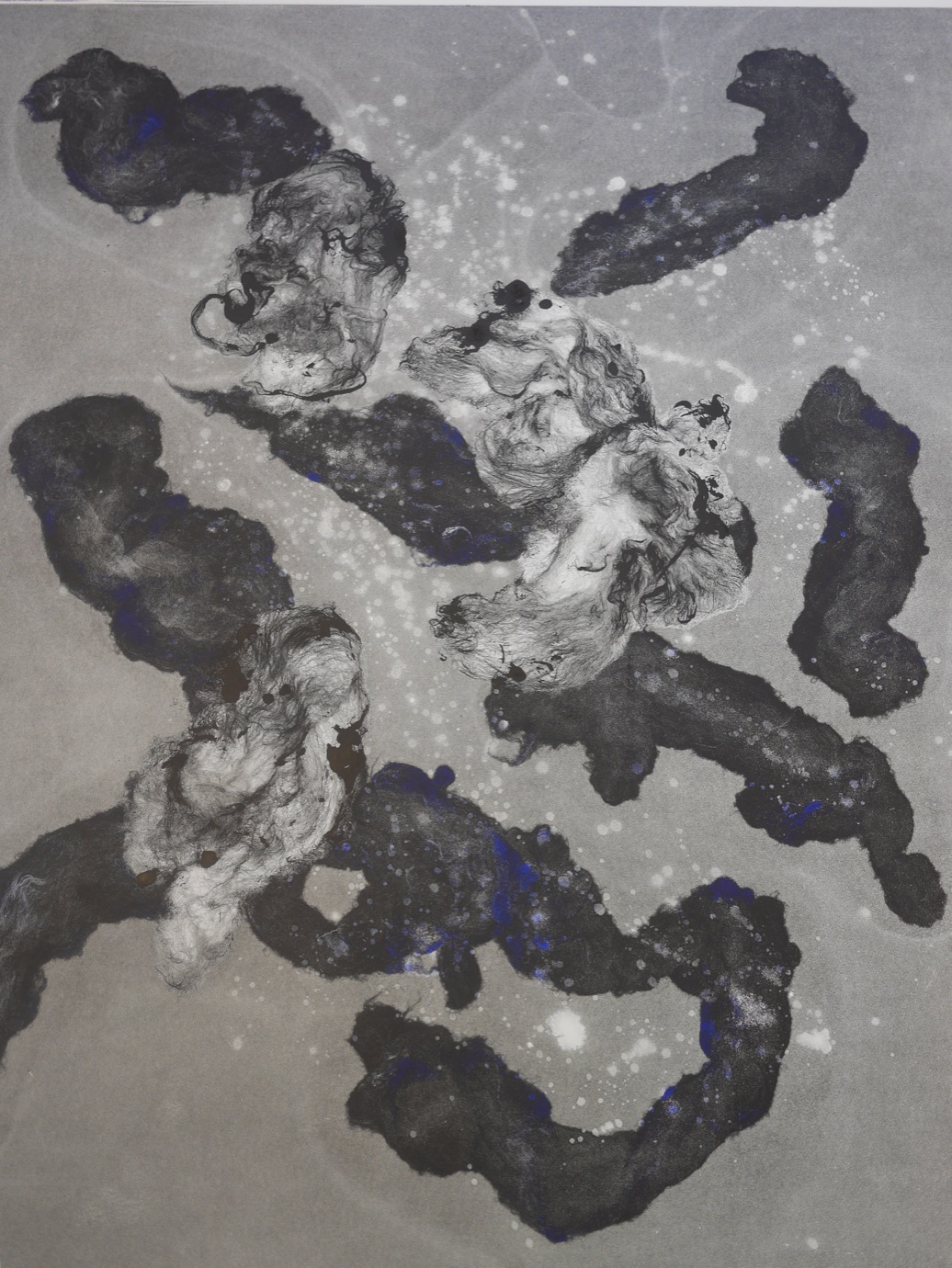

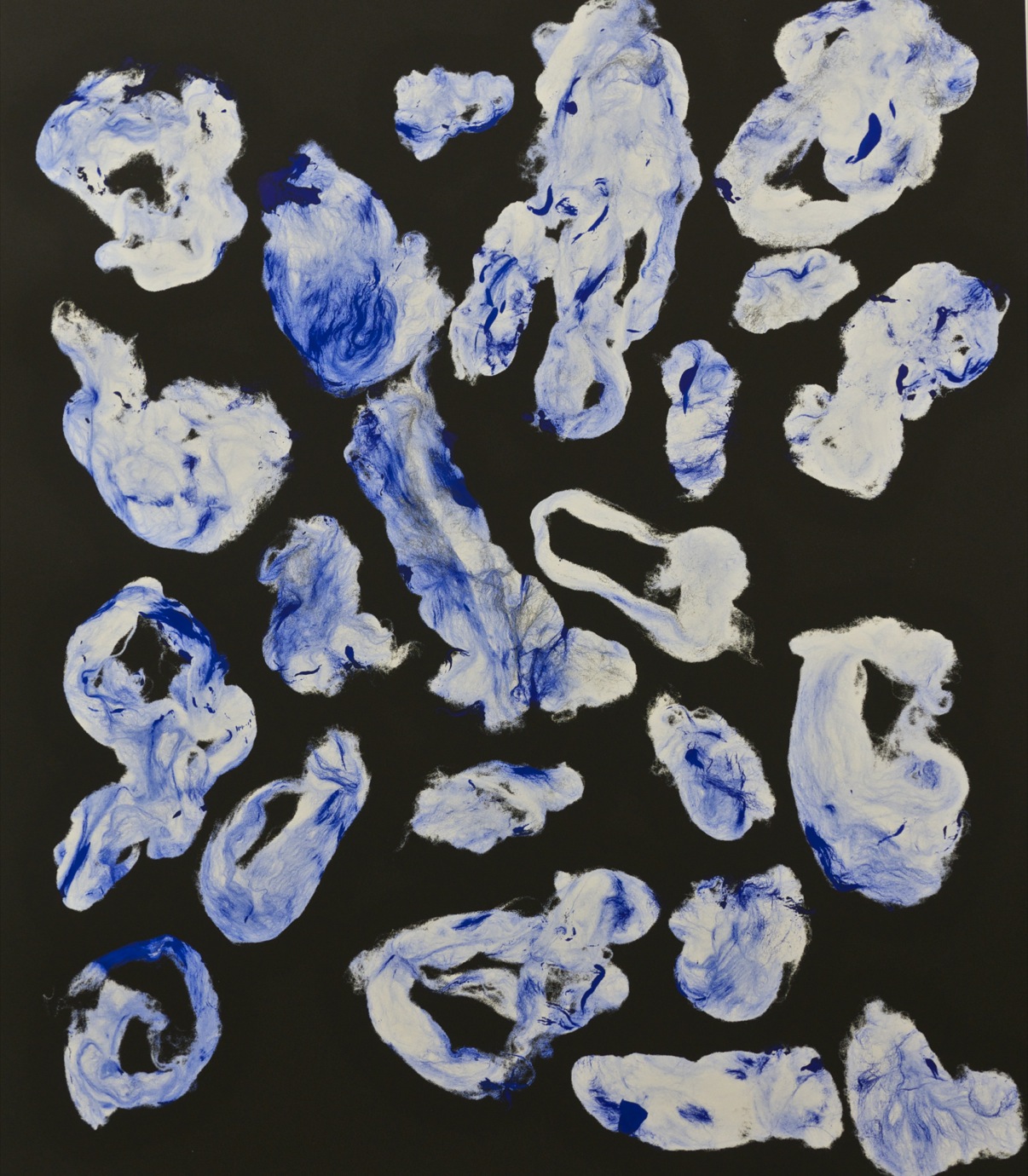

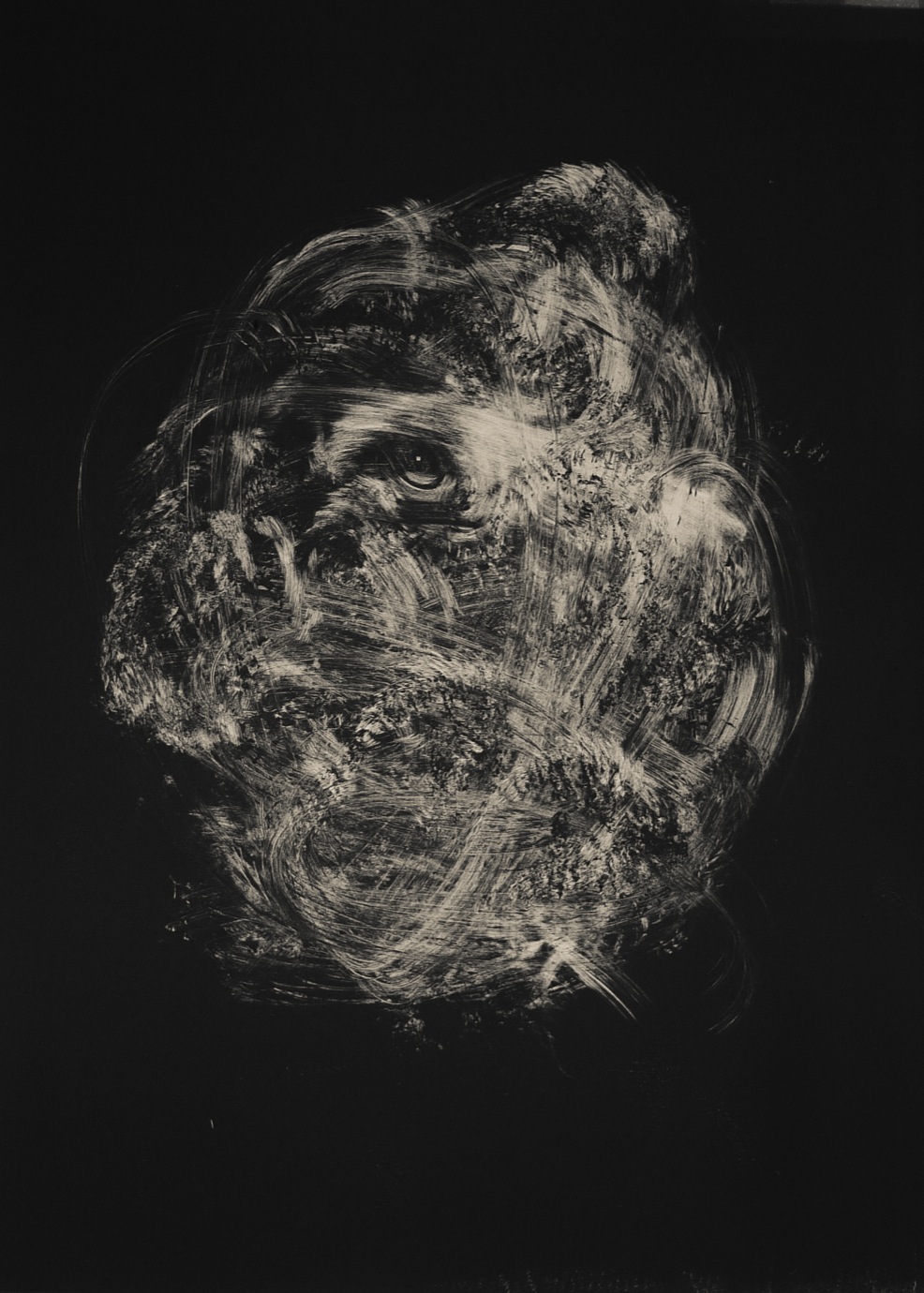

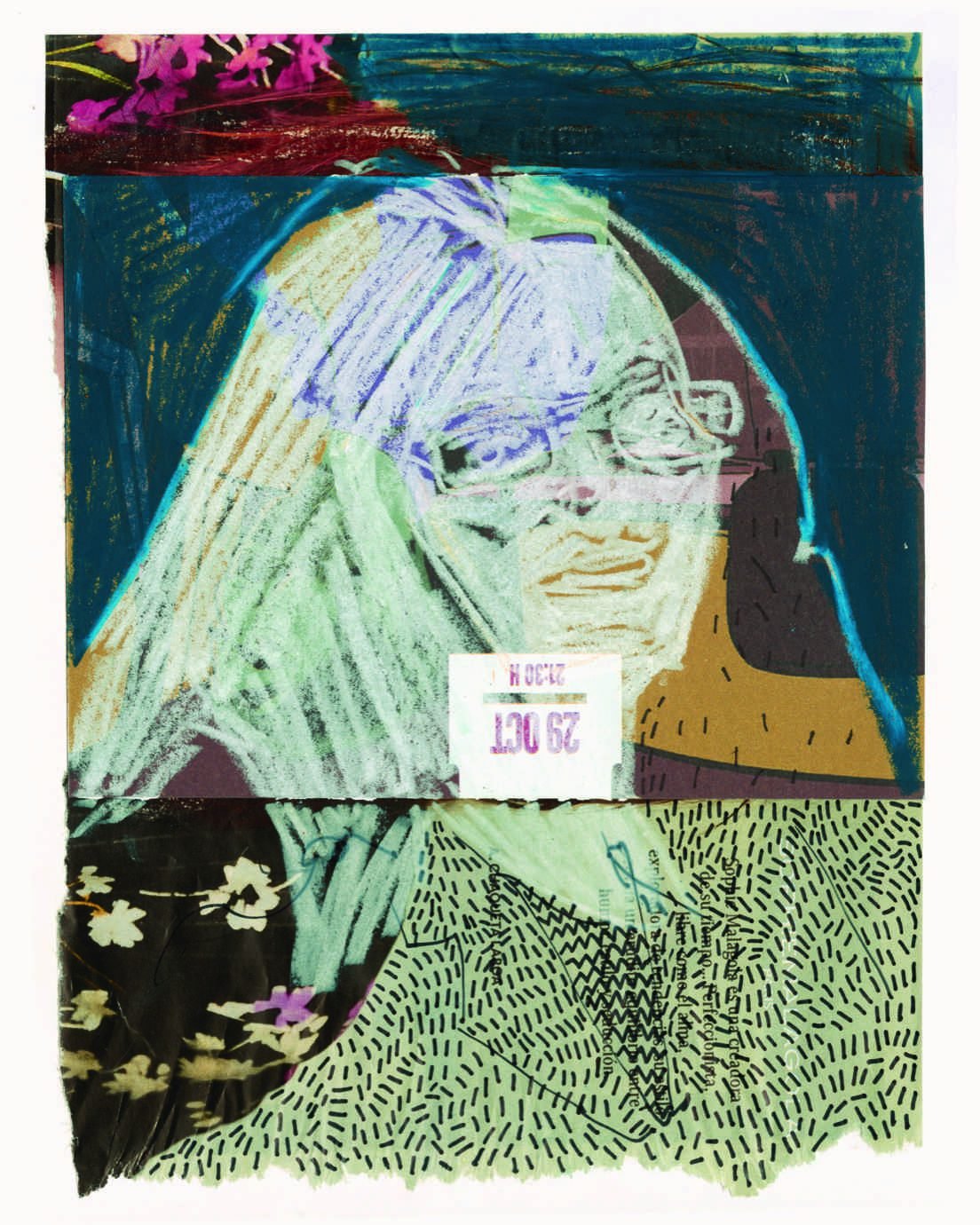

How to Appear Without a Trace, her first solo show in London, displays her most recent works on the two gallery floors, entirely self-curated. It is an extensive collection bearing witness to the amount of work and the cyclic evolving thought process of her practice. Detail is of course never left aside; the intricate and beautifully textured prints render an extraordinary amount of shapes, traces, blurbs and dots, in which one can read a certain fascination for the ghostly figure, the uncanny, the transformative aspect the viewer’s gaze is subjected to. No image is fixed. The process itself is one of discovery, for both the viewer and herself, as she either traces blanks through sheets of ink with her fingers and pieces of cloth to make an image appear, or awaits the unexpected shapes produced by inked up wool roving on paper.

“WHENEVER I MAKE A PRINT, IT CAN BE TRANSLATED AS SOMETHING INTESTINAL, LIKE BOWELS…”

For the first time, Coson has used colour extensively in her new large-format works, overlapping her usual choice of black and white with ultramarine blue. This adds light and warmness, rather than cooling it, and there is a definite change in the overall energy of the work: more ethereal and complex, thanks to the layered shades of black, grey and blue.

She softly comments on that recent development as she shows me around downstairs. “To me, it’s super colourful. I really like that the blue is a colour that is manmade”.

Besides the pristine rendering of the wool traces in black and different shades of ultramarine blue, the framing has also required a high amount of work and an equal amount of thought. The wool bundles are pressed inside three sheets of Perspex in two shades of grey (one darker than the other) and ultramarine, held together by screws and bolts, which evokes the process in which particles are squeezed in between microscope slides.

Some paper prints sit in traditional frames, while others are mounted on metal plates with magnets. “The reason I have used the tiny magnets holding the print up is because I really wanted to introduce this filed sheet as a reminder of the process. I find that to be such an important part of the entire show. It is capturing an instance in time, never to be repeated again because it’s a monotype. I cannot make another one.”

The metal sheet is where the ink get transferred from onto the paper, but in the case of the Perspex framed works, the wool is inked up and directly introduced in the press without a plate. “It all ends up on a piece of paper, so it’s kind of like a residue of the process.”

I wonder out loud if there is a correlation between the polarity of the softness of the wool and the harshness of cold, thick metal. “I definitely tried other fabrics, but I am really interested in the material of the wool because, again, it is the residue of something. It used to be part of an animal and now it is granted a second life.”

Moving on, she goes on explaining that the work has “an organic look to it. Whenever I make a print, it can be translated as something intestinal, like bowels…”