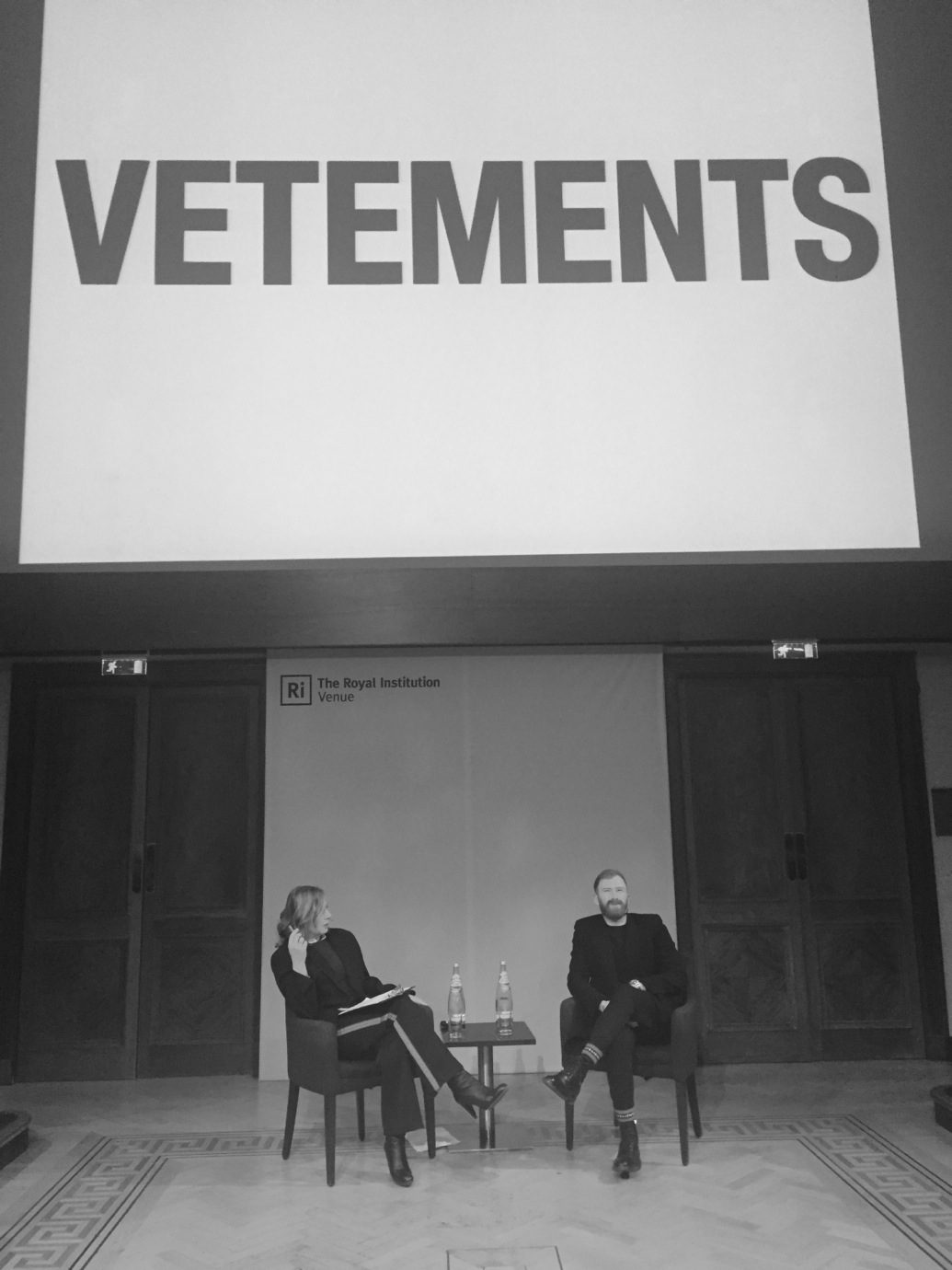

“LOOK AT THE HISTORY OF FASHION. NOBODY HAS EVER MADE IT BY FOLLOWING SOMEBODY ELSE.”

Cathy Horyn: When I started covering fashion, it wasn’t anything like this at all. All the designers were spread out, and in London, they were particularly on a shoestring. Not to be nostalgic, but when I first came to London, around 1987, the British Fashion Council was obviously active, but it wasn’t very organised. They did the shows at Earls Court then, at Olympia. There was a big shoe revolution going on, with young people coming out of Cordwainers, like Emma Hope. Patrick Cox had just started. Vivienne [Westwood], Rifat [Ozbek] and John [Galliano] were showing at Olympia. They were all very small. It was just a show here, a show there, and a lot of shows in very dumpy places in Soho. It was actually a vibrant time. It was the beginning of a street fashion movement. It wasn’t like today, where you have a hundred things happening all at once; you had much more of a dominant trend, then. American stores were here looking for new talent and ideas. We kind of complained about it at the time – that it was disorganised and always running behind schedule; shows would be an hour and a half late. You were in fire traps, seeing things that might not be good, dodgy or whatever. And then it became so organised, through the BFC, with everything running like a commuter train. 15 minutes. If you didn’t get there in the allotted time, the show would start. It was kind of stressful.

I used to feel, in the 80s and early 90s, that I came away with a bigger sense of London. McQueen was at Hoxton Square; you’d just go and hang out with him and see what he was making. You’d have Chalayan at Sadler’s Wells doing the show with the tables (AW00), then next season it was Lee’s glass box show (SS01). Which was also the same year as the Young British Artists show at the Royal Academy. It was really exciting to write about all that. There were new designers coming along – I don’t remember their names now, they didn’t survive. Then it was just time to move on. Lee and Hussein went to Paris. Things expanded out towards the Truman Brewery, which was still pretty good, but it just started to get a little more organised. You know what happened, I think? It just put everybody on the treadmill of the BFC schedule. And if you were on that schedule, you had to work to get off of it.

I went around with Jonathan Player, a photographer on the Times staff in London. Lovely guy. We had a pretty decent budget for the London coverage. Anyway, Jonathan would drive his car and we’d go all around, to shows, stores, appointments. After the recession, though, the budgets tightened up and we came to London for basically two days. It was efficient, I suppose, and now we shared a BFC car with another writer. But there was absolutely no breathing room. New York is now the same, over more days, with shows most nights at 9. You have to ask yourself if this method is human. The answer is probably to do less and go at your own pace.

The manner in which press covers young talent seems to also affect students. If a big publication decides to feature the ‘loudest’ designs of a graduate show, it signals to students that this is the avenue they should take – in order to receive press and be better known when leaving university.

I have no sympathy for that. I feel like it’s an old story. So many times I’ve written about it, and I have no interest in or energy for that.

For designers to try and please the press?

Yes, and I want to say to them: look at the history of fashion. Nobody has ever made it by following somebody else. As a writer, you can only say that so many times. I try to avoid those conversations because they take too much energy. There’s enough information out there that they should be able to figure it out themselves. For a number of years, I’ve looked at the work of young designers—for example, in competitions like the LVMH Prize, in a group. And I’m perplexed. Well, not perplexed. There are a lot of young designers who ask me for my advice, or they want an opinion. I look at the work and I think: this is really derivative. And how do I tell them that without hurting their pride? But what I do is, I move on. And it may sound cruel, but it’s only because I’ve been doing this a long time. My record is pretty clear about this. Whether you are an established name or an up-and-coming name, I support people who have the guts. Who have integrity and who have a vision. Even if they’re a really quiet designer – quiet meaning they’re not flamboyant, but they have good skills. It’s tough. I’ve sat in design classes in New York and talked to kids about this. It’s hard, frankly, for me and for them, because I’m sure they want to do their own thing.

“WHETHER YOU ARE AN ESTABLISHED NAME OR AN UP-AND-COMING NAME, I SUPPORT PEOPLE WHO HAVE THE GUTS.”

It’s tricky – it seems that with social media, there’s no ‘second chance’ for a designer. If you didn’t start out well, it’s challenging to ‘relaunch’ in two or three years, as everything is so public.

You have to know that at the end of the day, the things that make people successful at any job – whether it’s writing, in the arts, being a designer – is that they all have qualifications. Because being a designer, you’re a commercial person, essentially. Unless you have some other way of supporting yourself; you have some family money or a job on the side. Look at Azzedine [Alaïa], starting out as a nanny, basically, for a Parisian family and making clothes on the side. It just takes tremendous commitment. It also takes some degree of vision. If you were a novelist, you have to know what has come before you, and what barriers or ground you’re going to break. I think the same is true for designers. If you don’t have a solid history of fashion – even just the last forty or fifty years – I think it’s really hard to know what your place is in that world. How can you be different? Unless you’re someone like Rick Owens – a very unpopular designer in the early years. He had a cult following but it was tiny. Who wanted to dress like that? A lot of people did, but there was just as many going: “…Oh [pulls a face], you all look so goth and creepy.” And this is sunny Los Angeles. Movie star Los Angeles! Think about how alien that was. I mean, the guy’s got balls. He came to Paris, how many years has it been now? I’d say at least seventeen years. I think he was already there when I started at the Times, but just barely. He kept refining that vision of his. Today, he has a really solid commercial business; it’s not very big by big brand standards. I don’t know what the number is, but I’m guessing a $40 million business – which is a drop in a bucket. But it’s his. He’s got a good partner, and he evolves his aesthetic in a brilliant way. It surprises everybody, what he does. But you have to say that he started out with something that is original, to him. There’s nothing else like it.

Same with Helmut [Lang]. Every example I can give, they’re all people who had a very good sense of what came before them. Raf [Simons], when he started, was very conscious of Helmut. He was very influenced, and he’s always said that. That’s often a missing thing with young designers, just not having enough historical knowledge. I look at things and I go: “It’s really derivative.” And people have to learn by imitating, I get that, and that’s very common. I think Jonathan Anderson did that. But he has other important skills. He’s got innate good taste. He has a very good curatorial eye, which is essential if you want to work for a big house. It’s no longer one creator, like Cristobal Balenciaga; it’s barely like Azzedine now. Azzedine is so unique. But Jonathan has that curatorial ability. And he has major ambition – also crucial.

The people that work for him say that he’s very good at getting the best out of everyone.

It’s the same thing Raf has: they know how to build a team. They know how to inspire people. The proof is in the pudding at Loewe. It has its own place in the big fashion cosmos. I don’t sometimes get Jonathan’s own stuff, but also to be honest I don’t pay so much attention to it now because I don’t come to London. I remember when he just started out, he was just trying out everything. A little Comme des Garcons, a little this, a little that. It’s okay. He did it with a genuine spirit of experimentation, trying. But he’s so mature now as a creative director. He’s really good at it.

Yet getting to that level is challenging, as it takes more than just being a good designer.

Yeah, and some of those (young) designers should really think about trying to get a job with a large company. Whatever that company is – it could be Levi’s, a fashion house in Paris, a company in London – and get as much experience as they can. They need to learn how to work in a team, to be a second.

The current generation of students entering art schools have already built up big followings on Instagram – for some, going to Central Saint Martins can be seen as a continuation of the show that is their digital life. From a psychological perspective, it’s a difficult industry as the people are driven by applause. In other industries, it would rather be money or job security.

I always admit that shortcomings are generational. And I think those generational differences are becoming more and more extreme now. One of them is because of social media and the whole selfie idea, having followers, being public and sharing. I don’t share. I grew up with a generation of designers that was very protective and competitive. They were also respectful of the work. Yes, they liked the applause too. They needed to feel on top, that’s human nature. But they still did the work, the heavy lifting.

Does this generational aspect also affect how we can define clothes ‘by their time’? In the 80s, clothing was more inherently linked to what was happening in the world. Now everything feels like a big soup of everything.

For sure.

It must make it more difficult to critique something.

It’s hard. I’ve noticed that it really accelerated in the last three or four years, where I feel really cautious about what I’m going to say when it comes to a generational assumption. When I see a brand that looks like what Dior has been trying to do, people start talking about: “Oh, it’s for the millennials.” We don’t even know what the millennials want, and I feel presumptuous to even think that.

“I THINK MILLENNIALS JUST HAVE SO MANY DIFFERENT MOTIVES. I JUST HATE THE IDEA OF DRESSING PEOPLE AS A GROUP.”

We are millennials and we don’t even know.

I think millennials just have so many different motives. I just hate the idea of dressing people as a group.

It’s not possible, because we’re so diverse.

It’s a very challenging situation, because of all the different personalities, and all the different micro-groups that spin out. I remember people talking about this like ten or twenty years ago. And it’s exactly what Alvin Toffler said when he wrote Future Shock: it gets smaller and smaller, down to groups or obsessions that are mere particles, in Toffler’s language. Actually, Balzac talked about the levelling process back in the 1830s, mainly because of the shift from the individual creative world of the 18th century to industrialization and mass culture in the early 19th. Of course, the process has just accelerated in our lifetime because of mobile and digital technology.

Vanessa Friedman’s review for Gucci mentioned that when there are so many disparate references, and everybody embraces this, then they will all start looking the same. What she said about Gucci seems true about the industry at large – so many designers take ten different aesthetics and style them together.

Like Vaquera, a relatively new label in New York. They’re charming kids. I couldn’t go to see their show, but I saw them the next day in one of the designers’ apartments. They just let it happen. They told me they went to LA to get inspiration. I was like: “Great!” I mean, go for it. They all have jobs. I am hopeful about them. But one thing I’m not hopeful about is that they’re a group, and it’ll go so far and then they’ll break up, from unforeseen pressures or differences. Perhaps not, though.

You think groups never work?

They seldom work. Can you think of one?

Do you think it’s because of internal tensions?

Personalities, not having enough money. Couples work, usually because one is a business partner and not necessarily a design person. Historically that’s how it’s been. There probably are some couples who are both designers.

The Rodarte sisters.

Of course.

When Valentino was done by Pierpaolo [Piccioli] and Maria [Grazia Chiuri]. But I think it was better when they were together. We personally strongly dislike what’s happening at Dior now.

I’m not crazy about what she’s doing at Dior, a house I’ve always admired and found fascinating. Her shapes are repetitive and, well, in my view, not up to the legacy of the company. I like what Pierpaolo did this season at Valentino because it spun off couture, and I loved his July couture show. He’s really good with colour.

Somehow, Raf Simons at Calvin Klein can be seen as a team of three – Pieter Mulier, and Matthieu Blazy. It’s one name at the top, but they do feel like a group. With Olivier Rizzo and Willy Vanderperre, they all come as a gang.

And Sterling Ruby. Raf was like that from the start, with Robbie Snelders, who was a big influence on him. Robbie didn’t really have an official job in the very beginning. He was a model and sort of a muse. But then Raf also had a lot of people around him who were all anonymous. If you can ever get your hands on two videos that he made…One of them you can probably find: 16, 17, How To Talk To Your Teen. Try and find that. They didn’t do a show that season, and it was the early days of video, so it was quite novel. I think it was ’96/’97. It’s so good. It’s all about kids blowing off from school in Antwerp, skating and hanging out with their friends. The other video is, I believe, from Raf’s second collection and in it he showed both men’s and women’s clothes, mostly tailoring. The scene is a small, dark, glamorous party. Veronique Branquinho was in the video. It is so sexy and cool. It’s all of who Raf is today.

We wanted to touch on how press works with regard to featuring young talent. All publications are so driven by exclusivity that they wouldn’t write about them twice in half a year. While logically it is the role of press to support these designers, not just make a “story” out of them.

That’s very true.

“I’M NOT A SUPPORT SYSTEM. MY JOB – ESPECIALLY AT THE TIMESBECAUSE IT’S A MAJOR PAPER – IS TO INFORM MY READERS, NOT TO WORK FOR DESIGNERS AND THE INDUSTRY.”

That’s when designers are trying to fly before they walk. In two or three seasons, they’re not interesting for anyone anymore.

I can’t speak for magazines, but newspapers are very much guided by having just written about a person. One of the advantages of being a critic or columnist for the New York Times is that I had control over my space. I decided what shows I was going to review. I could review the majors, and the minors that I really liked. But it also meant that I could go back and repeatedly write about people I felt were talented. No editor could tell me: “Oh, but you just wrote about her.” With feature stories, it’s a different matter. If a newspaper did a piece on someone or a company, it won’t revisit that subject for awhile. But it’s tough. I once said in an interview: I’m not a support system. My job – especially at the Times because it’s a major paper – is to inform my readers, not to work for designers and the industry. And I think newspapers should continue to take that position.

The lack of criticism seems to be partially what has made the industry unhealthy for young designers. If there would be a higher standard for everybody to start, perhaps the landscape wouldn’t be as messy and crowded.

I think that’s probably true, but there are so many determining factors about that. Nobody anticipated that social media would have this impact. That people could become pretty well-known through their Instagram account, and that you could then have people who would say: “Well, she’s moving merchandise for us.” Or, “She brings more people onto my Instagram.” Many established designers are incredibly loyal to the magazines and the newsprint press. Just from a long-standing habit, even though they’re very involved with the ‘influencers’. Again, I think what happens is that you get this fragmentation. Voices come from all different places.

What do you read these days?

A PR guy recently asked me what I read, and I said: “I don’t read too many fashion magazines.” There was a time when I read everything, always Vogue, Bazaar, i-D. I almost never buy them now. Maybe it’s just that my own interests have changed. Maybe it’s also because I’m online so much, that I’m looking at other things that are online. I don’t really think about going to the newsstand nowadays. There was a time where I’d look at Gentlewoman and 032c, those were my favourites. I just feel like you exhaust what you want from that content. I feel like there are so many other things going on in the world that I want to know. I want to do other things, I want to think about things. I spend a lot of time thinking about the past – I mean, the way past. I’d rather read a novel or something else.

“I CAN’T IMAGINE THAT THERE WOULDN’T BE A MARKET FOR SOMEONE WHO CAME ALONG TODAY AND WROTE WITH CLARITY, HUMOUR AND INSIGHT.”

What are your biggest concerns for fashion criticism now, for anyone in the field starting out? Many of our writers come from a Fashion Journalism pathway – is it still worth it to do that type of education? To so many people it’s a dying profession.

When I think of the criticism I really love, whether it’s of books or films or pop culture, it’s when someone is a really good observer of things. I go back and read some of Michael Roberts’ early writing, before he moved into doing illustration and photography. He was great, and I can’t imagine that there wouldn’t be a market for someone who came along today and wrote with clarity, humour and insight. If they could look at something in a fresh way, and they could be really selective about what they’re doing. Don’t feel like you have to go to all the big brands. I would read that column, and be so envious, if that person had a really fresh point of view. If they did it on their own, and they saw things and related it to art history – or music or television. Related it to other disciplines. That would be really interesting.

Thinking about editors, do you think there’s still a place for big, almost celebrity-type editors? The Anna Wintours and Graydon Carters. It’s not that apparent in the younger generation – are companies leading them towards teamwork?

I think it’s cyclical, it’ll change again. Edna Woolman Chase was a dynamo at Vogue for decades. Carmel Snow was a dynamo at Bazaar, and so was Diana Vreeland. I think you’ll see those kinds of people again, but it may not be for another decade. I’m convinced everything comes back – there will be a demand for brilliant editing.

After reading Condé Nast’s biography, and recently all the tributes to Si Newhouse, one can spot lots of similarities in their personalities.

They’d rather let someone else shine, and make sure the people working for them are getting what they need. Did you read Graydon Carter’s piece on Si Newhouse? It has great anecdotes. You know, these guys had a lot of money, and they had a vision. They loved quality, they loved magazines. Look at the Times, how much it has changed. There were periods like the 1960s where it was phenomenal, but any period where it was phenomenal, it was usually because somebody dynamic was there. The paper has always given liberty to that, whether it’s in politics or fashion, society writing or social commentary. Look at Vogue: Anna is a journalist and came with a really broad background, she has that nose and sense of greatness. The woman I work for now, Stella Bugbee, is very much a journalist. They think about what the news story is, and about what is happening in fashion and pop culture and music. She really has a broad view, and you need that. I wonder whether that journalistic training is going away.

You mentioned in several interviews that there’s space for a blog to exist from ‘inside the industry’ that speaks up about issues in fashion houses. Why do you think no one has started it yet?

It may be because you have to be a true journalist. You have to be motivated by a journalistic thing and have the skills – to interview people, root out information, meet grinding deadlines. Reporters are all out there reporting on the American political scene now, and I think that if you’re a hungry investigative reporter, that’s where you’ll go. You probably don’t think about reporting on LVMH or Kering, though why not? They’re powerful organizations. They’re not all about the glitz and glamour.

Thinking about approaching publishing from the sidelines, as you mentioned earlier: it’s difficult for young publications to establish a solid position in the industry without building relationships with big brands, PR companies, agencies and the like – who all have a big influence on what is ‘approved’ or not.

The danger is that as more people come of age in the business, whether they are PR or writers, they will take it for granted that a subject can have photo approval or their rep will be able to control the content of a piece. That I find very disturbing. It just becomes this accepted thing, and then you have people who will be shocked when a reporter does ask a hard question. Inevitably, a group will come along who questions this practice.

We recently spoke with somebody in PR about the services they offer to designers, and if it’s really worth paying x amount of money for it. He admitted that most of it is just a mirage, and that often PRs can make up facts, and not put in the effort that designers think they pay for.

I had a PR guy once tell me that the only reason he was still in business was because clients keep making the same mistakes over and over again. Fashion attracts so many different kinds of people. They come in very naive, and some stay and really develop.

It’s all about manipulating what the public thinks, in fashion and elsewhere. That’s what companies are most concerned about, it seems. I feel like I very much lived in a golden time for fashion as well as newspapers. I got to know designers who had connections to the 1950s and 60s, and loved telling stories, and also with designers who had a big impact on the early 21st century. And I worked for newspapers and magazines that totally protected me as a critic. At the Times, I often didn’t know when advertising was being pulled because of a review; the editors didn’t put that pressure on you. And no one ever asked me to change something, to be nicer. I always worked in the assumption that I could do whatever I wanted. But I think that’s also part of the education of a journalist. You know what’s fair and in good taste.

All things considered with both design and writing, it does feel very much like a positive time. People are tired of quantity, so they’re looking for quality again. It seems as though taste is becoming more refined.

I’m always optimistic.

Tired of the screen? You can read this interview, and more, in our fifth print issue (order here).

This interview was released previously through the Business of Fashion.