Bianca is a designer gifted with both: even a passing glance at either of her collections reveals a designer well-versed in the heritage of time-honoured suiting, and it is immediately clear why she was handpicked by Harris Elliott to show as part of 5 CURATORS/ONE SPACE. But, while her work was applauded for the technical proficiency it demonstrates, not all of the exhibition’s attendees were as quick to grasp its conceptual depth: “My pieces were…well, not everyone understood them,” inviting such comments as “Your work is really theatrical! Have you thought about going into costume design?” For the record, no, she has not. And for good reason too – after all, how many graduates can count industry titans like Charlie Porter among their ever-widening base of fans less than a year after graduation?

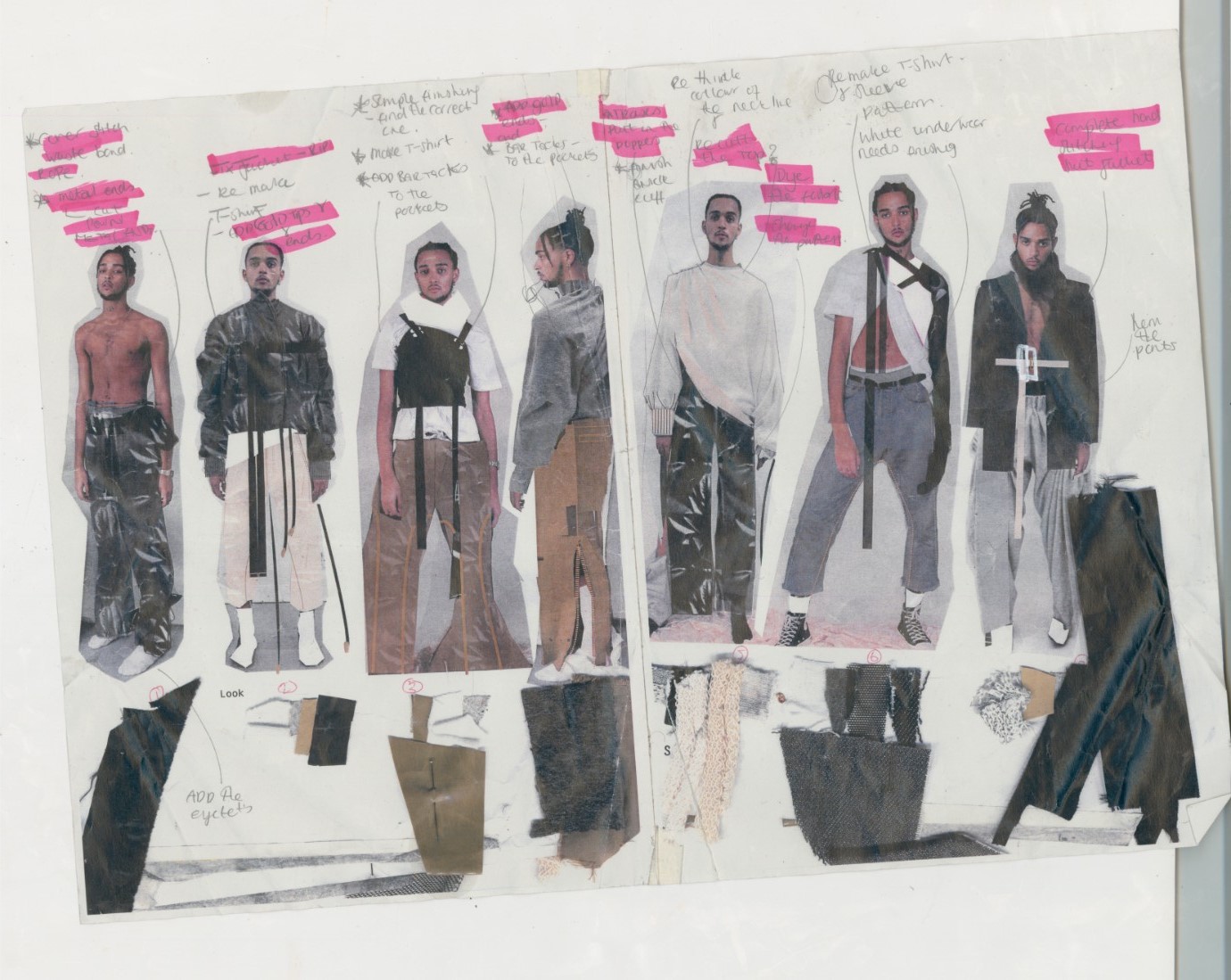

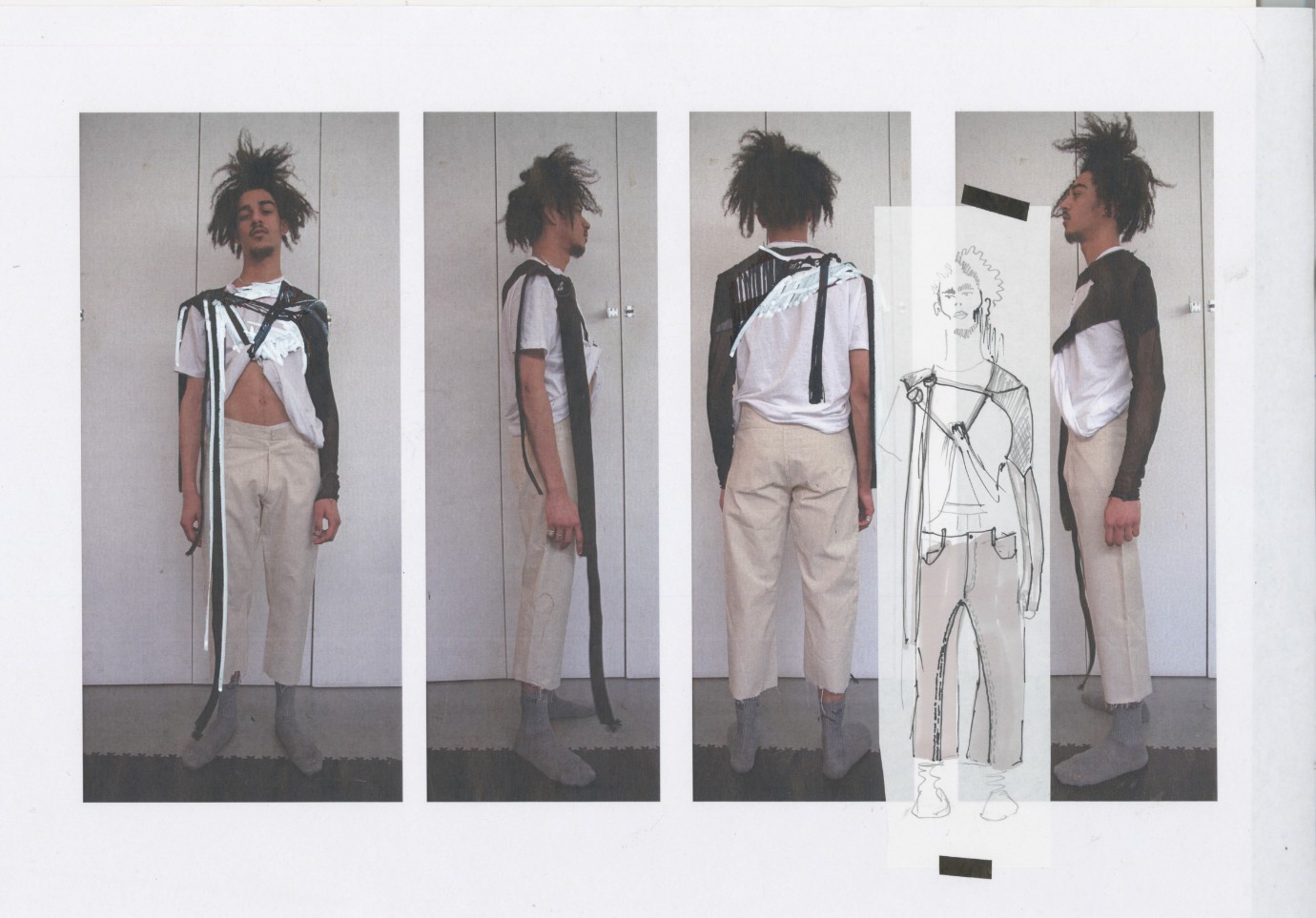

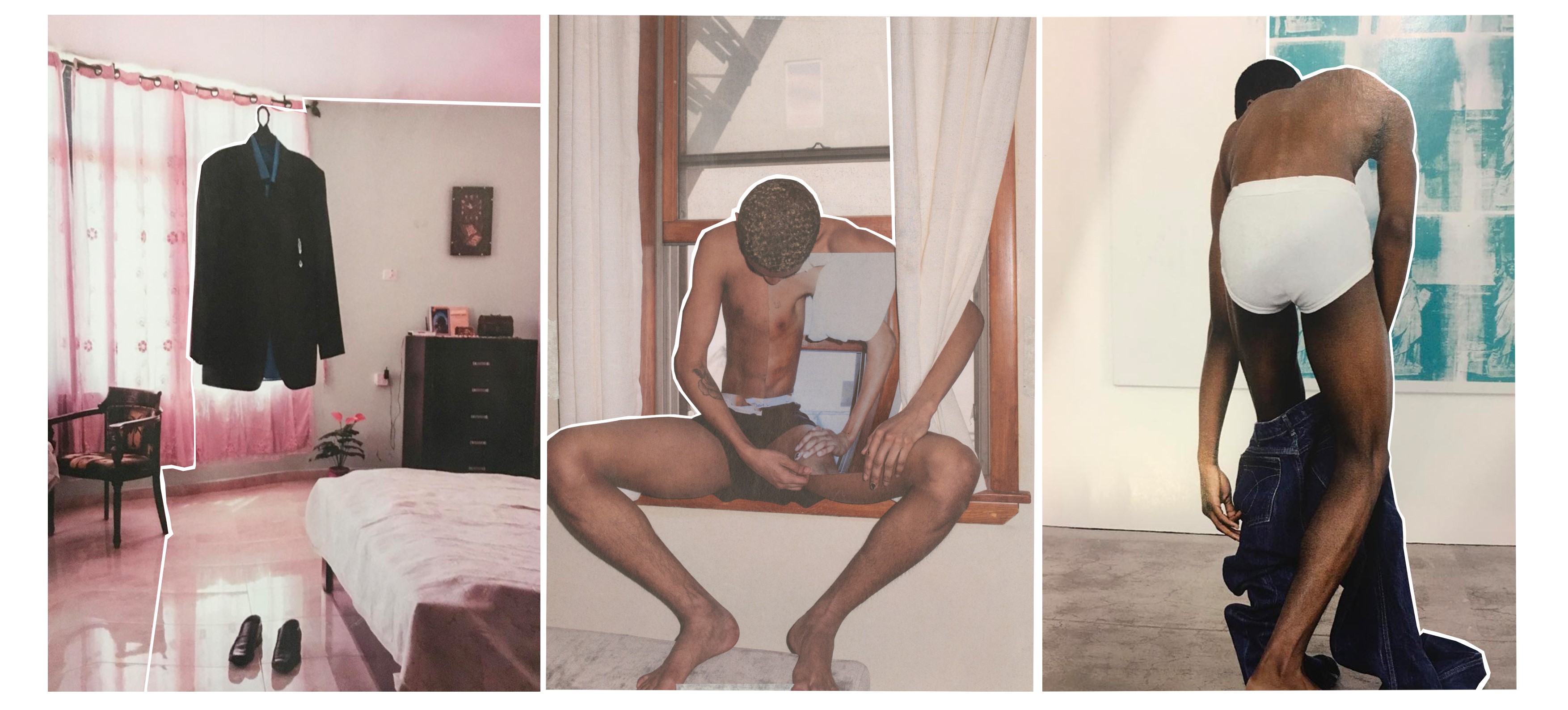

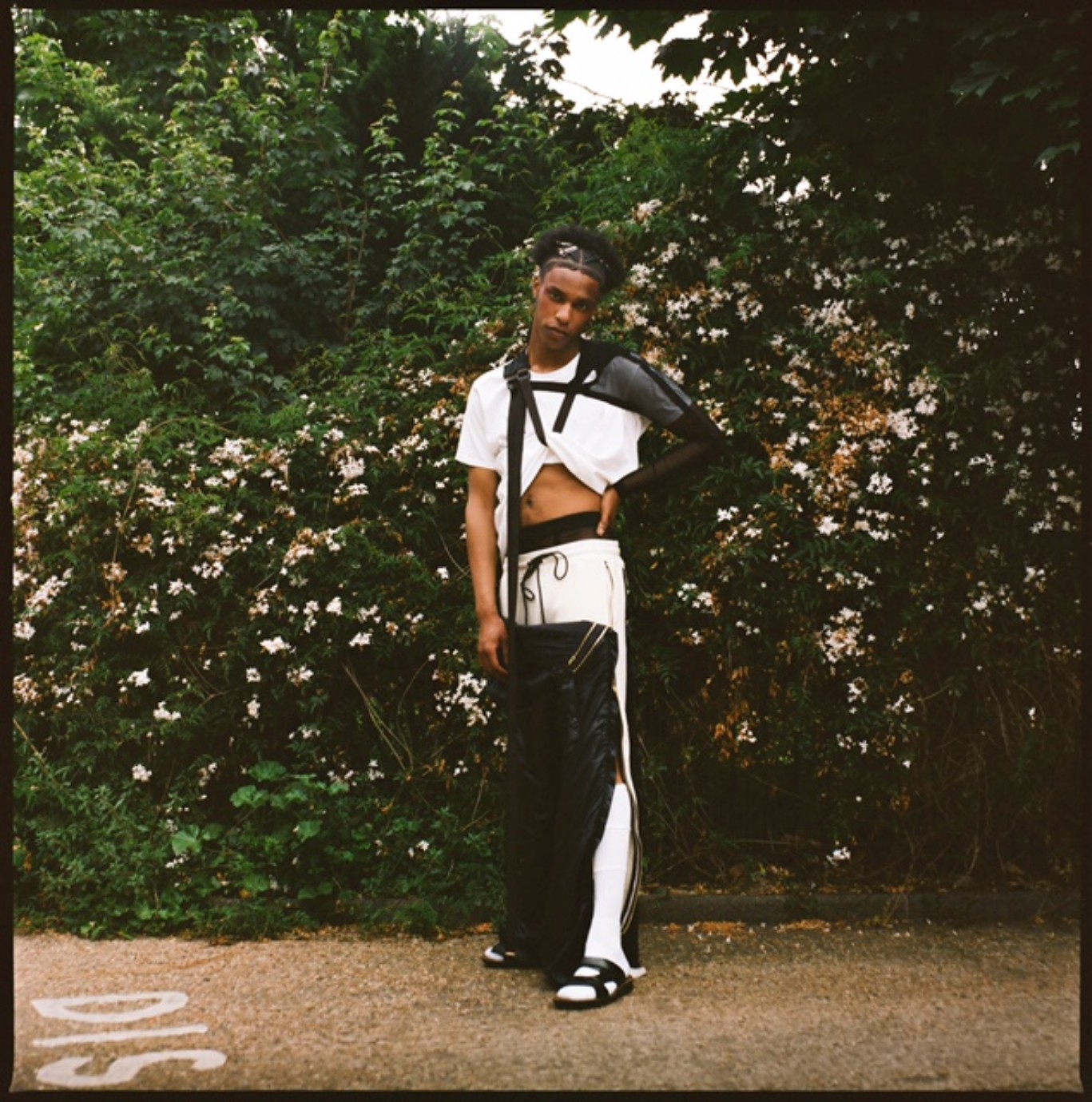

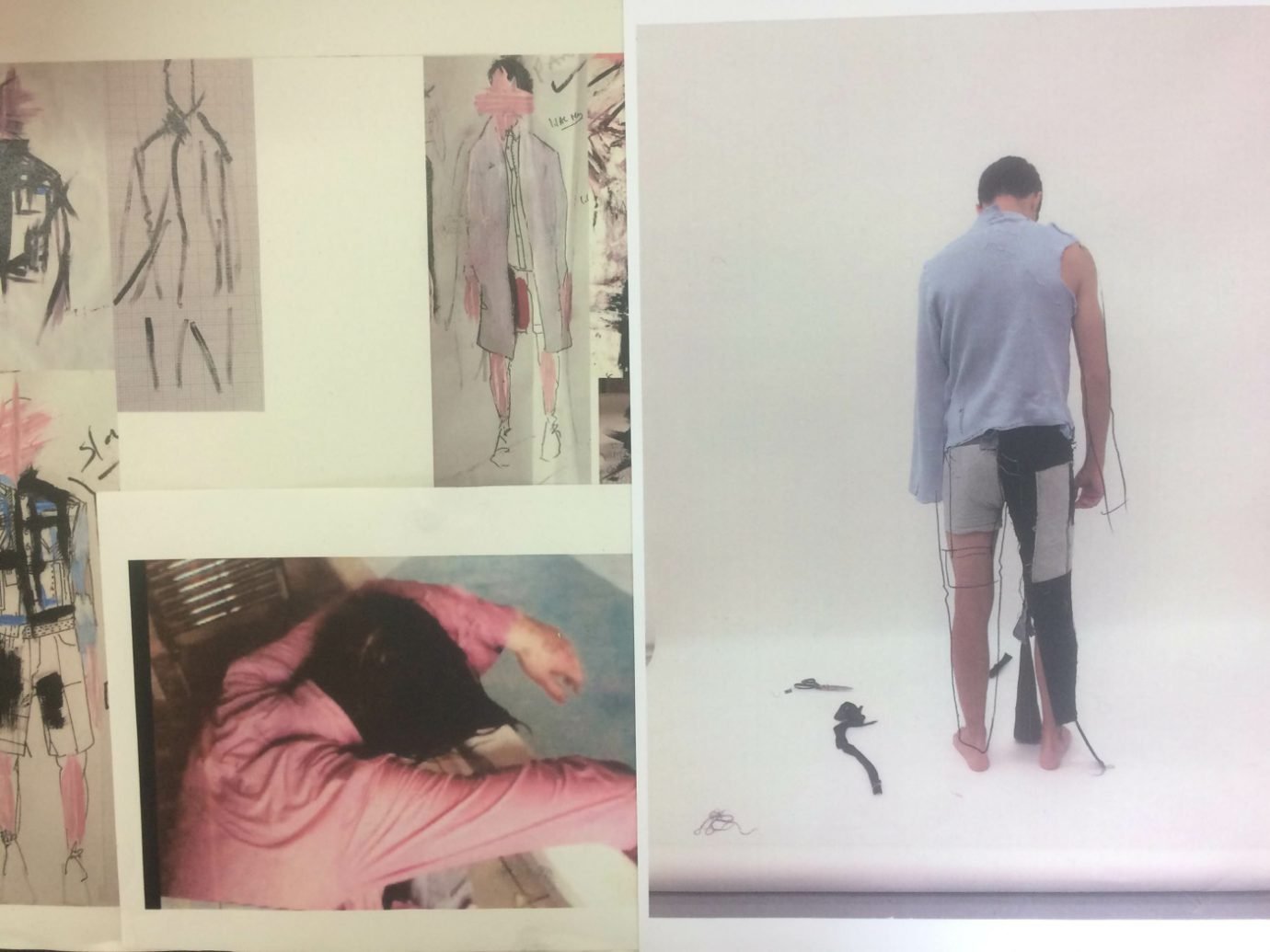

In London is the Place for Me, her first foray into menswear, she presents a retrospective portrait of Caribbean life in Britain, exploring notions of home, identity and memory: the patterns on quilted khaki jackets mirror the wallpaper of her grandmother’s house, and delicate white lace suggests frilled net curtains; the first look of the collection, a gentlemanly pinstripe suit, would imply an overbearing, masculine severity were it not interrupted by wide, fuzzy bands of cobalt blue carpet. This is no novice work, requiring a mastery of advanced technique, a steady hand and an eye for precision. That does not, however, go to say that there was no error in the trialling process: “There were many things that almost went wrong,” remembers Bianca, recounting her first attempts at felting and cutting suit patterns, “it was my first time making menswear, and I had no idea where to begin with making a suit. I bought one, took it apart and thought I’d be able to make a pattern,” with little initial success.