Throughout his childhood, spent on Norfolk’s picturesque coast, Wallace built things, a trait he inherited from his father. “My dad is very… I don’t want to say DIY, because that sounds reductive… but he built a car when he was eighteen,” Wallace says, speaking with careful precision. “He’s always been extremely practical.” To this day, Wallace tinkers with materials and explores physical shapes by devising his own lamps and building chairs, tables, and other furniture. This exploration of product design has influenced the way he makes clothes – as a BA student he designed a wooden frame that would fit around a person’s body.

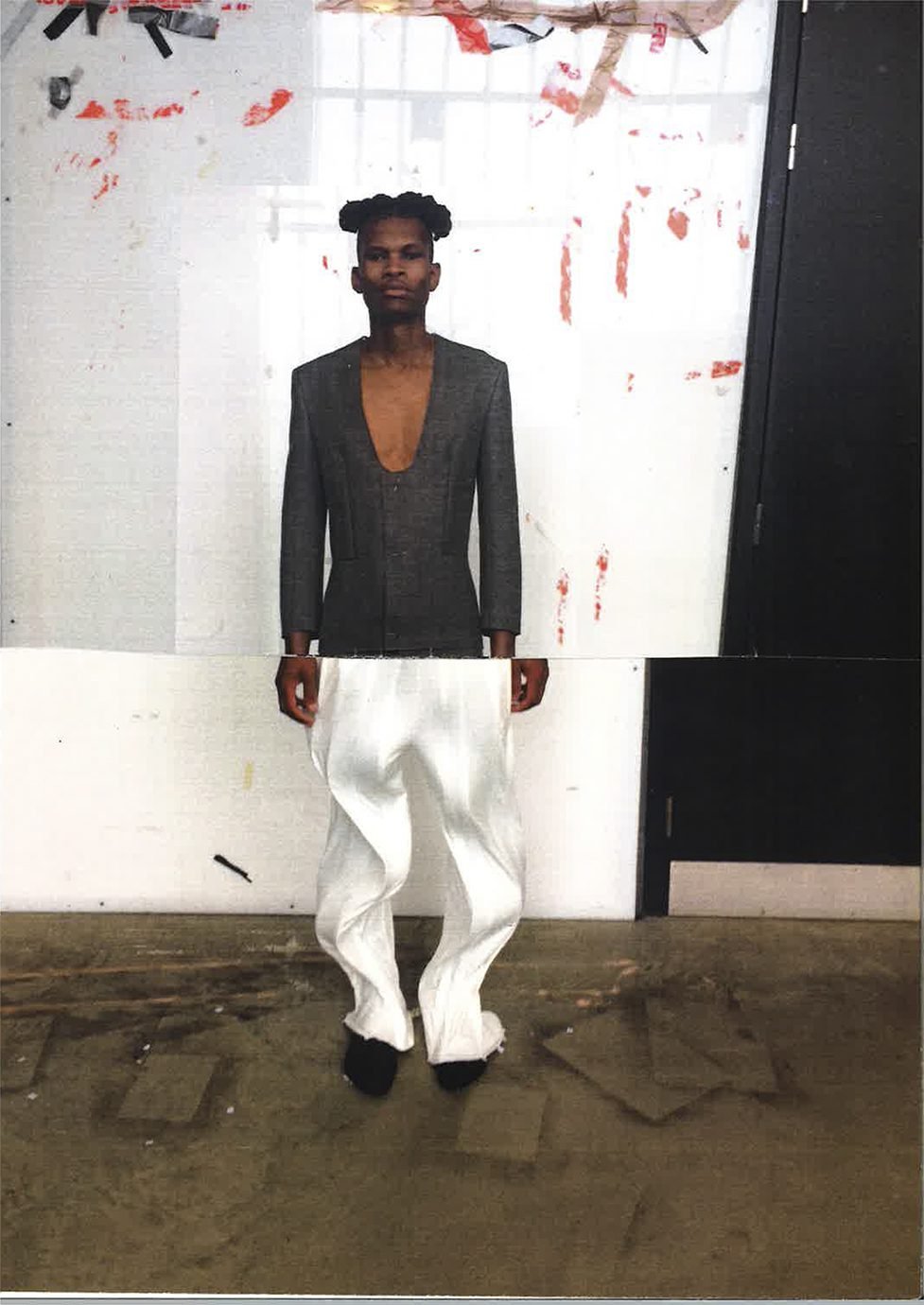

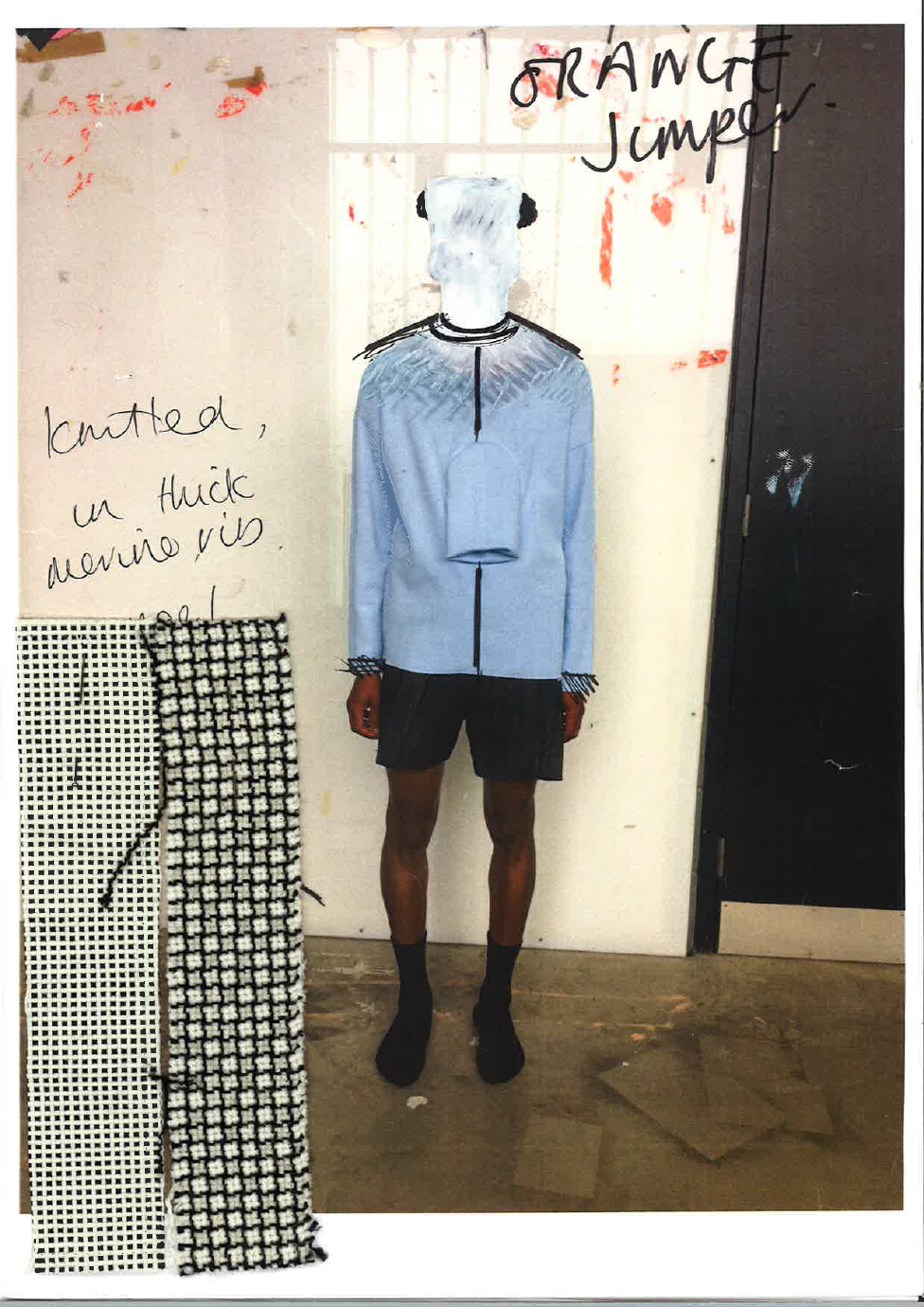

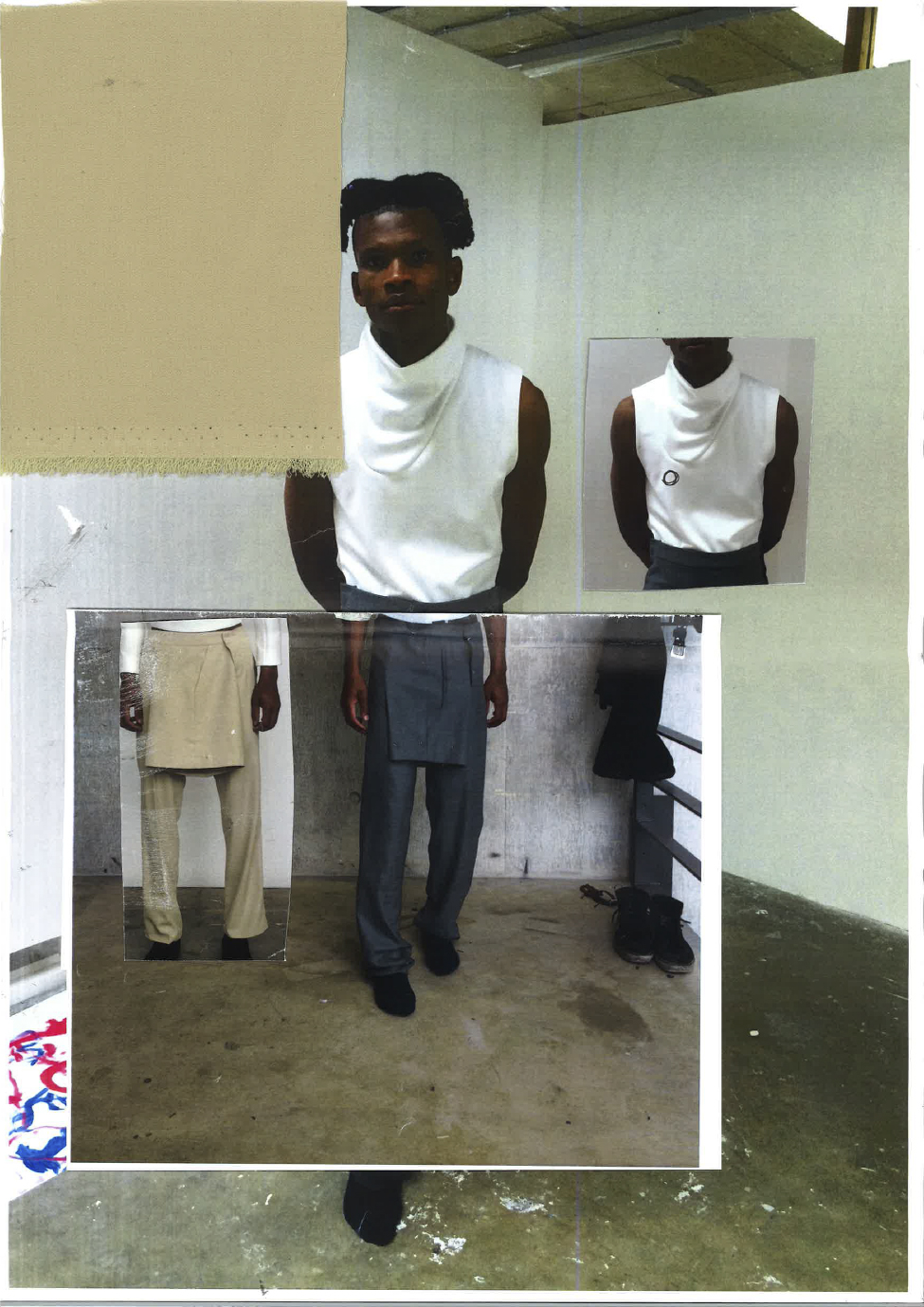

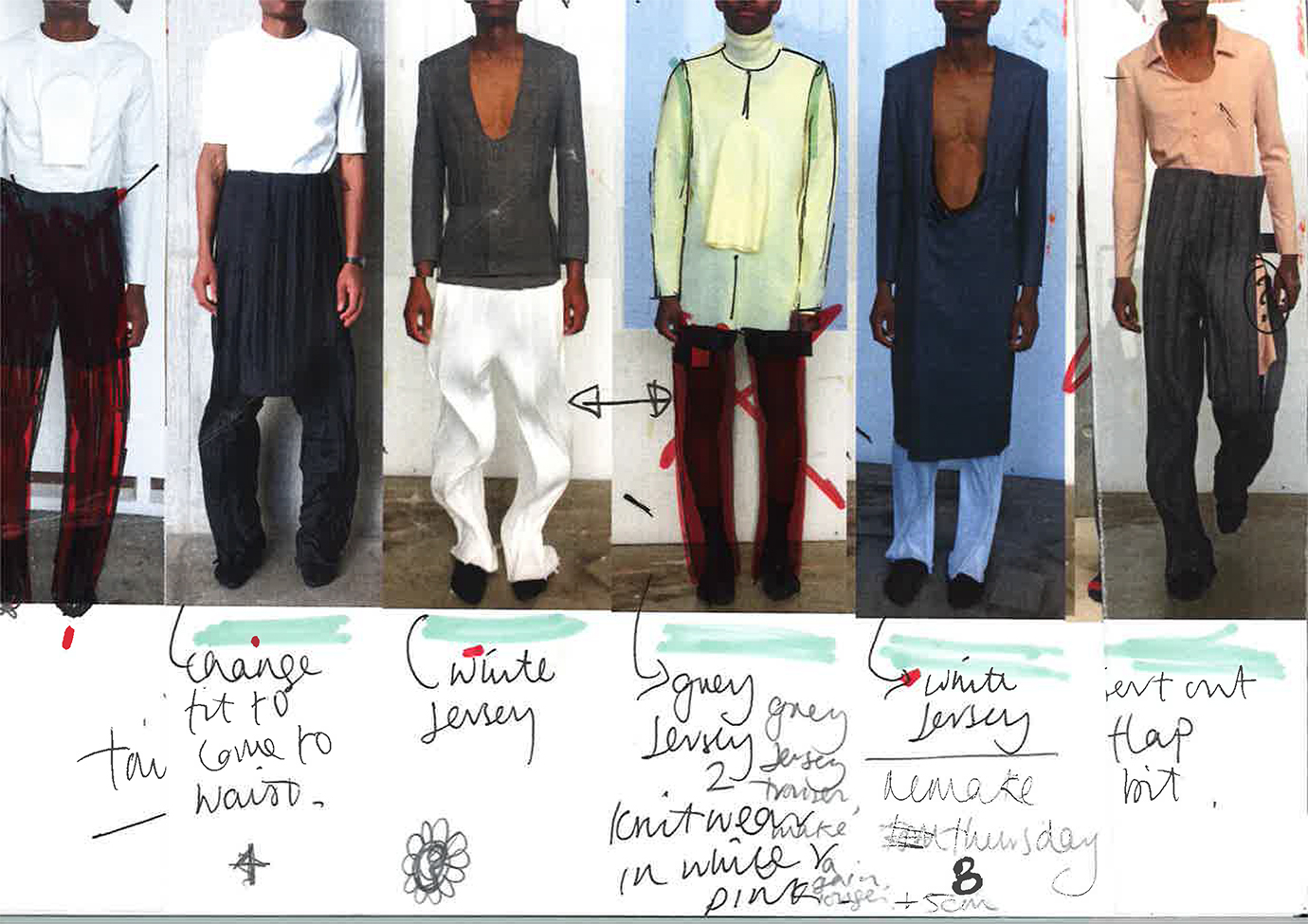

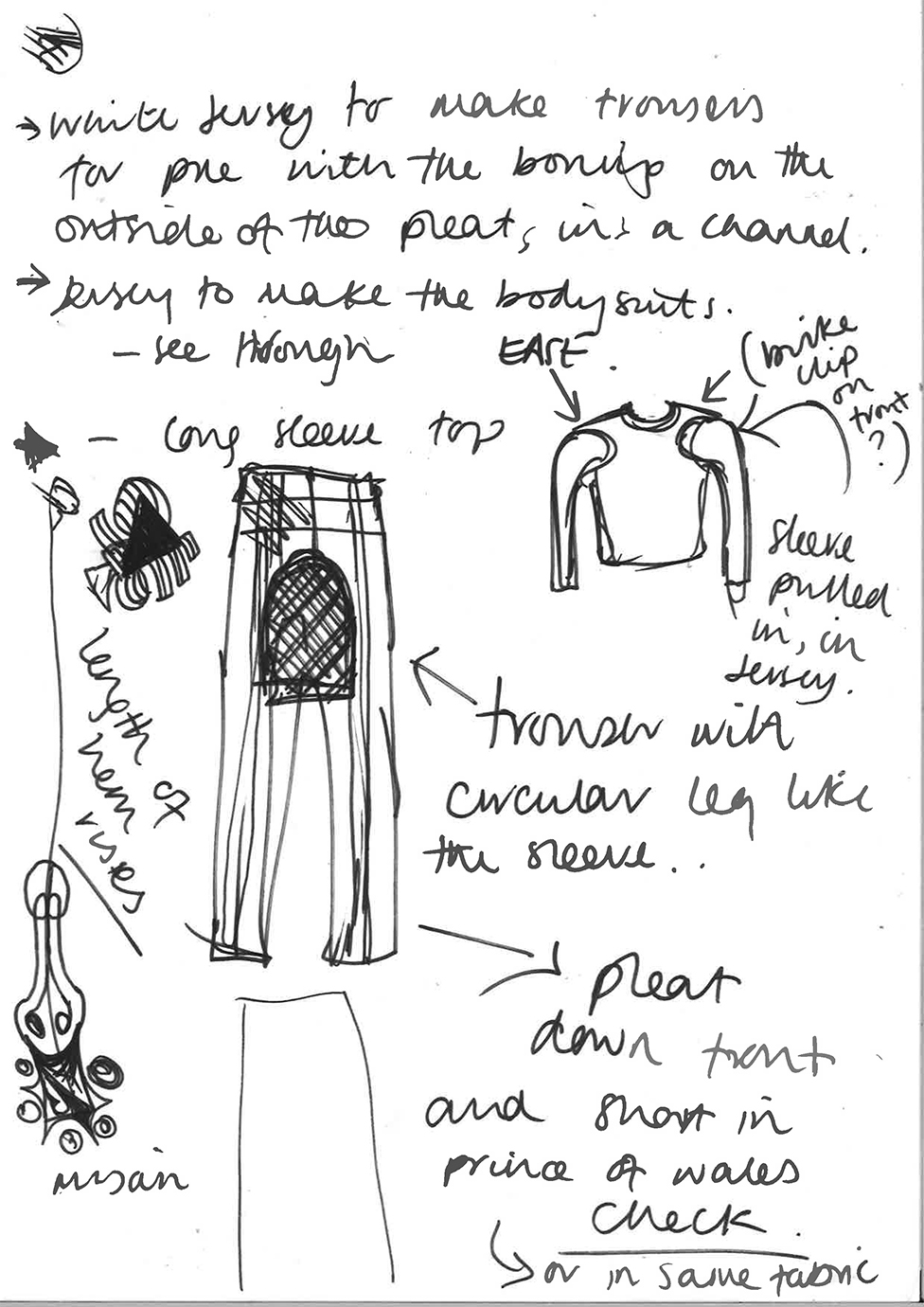

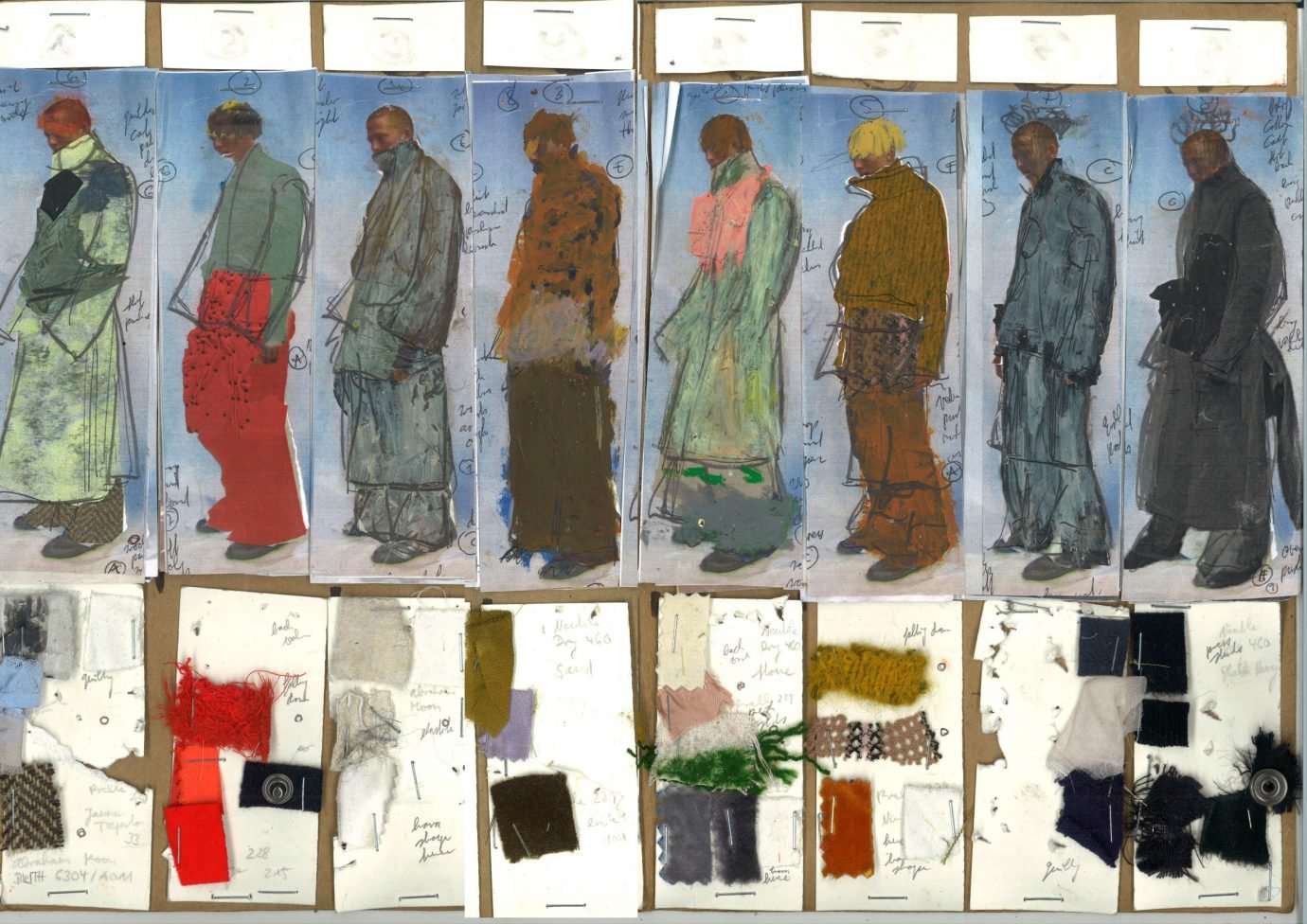

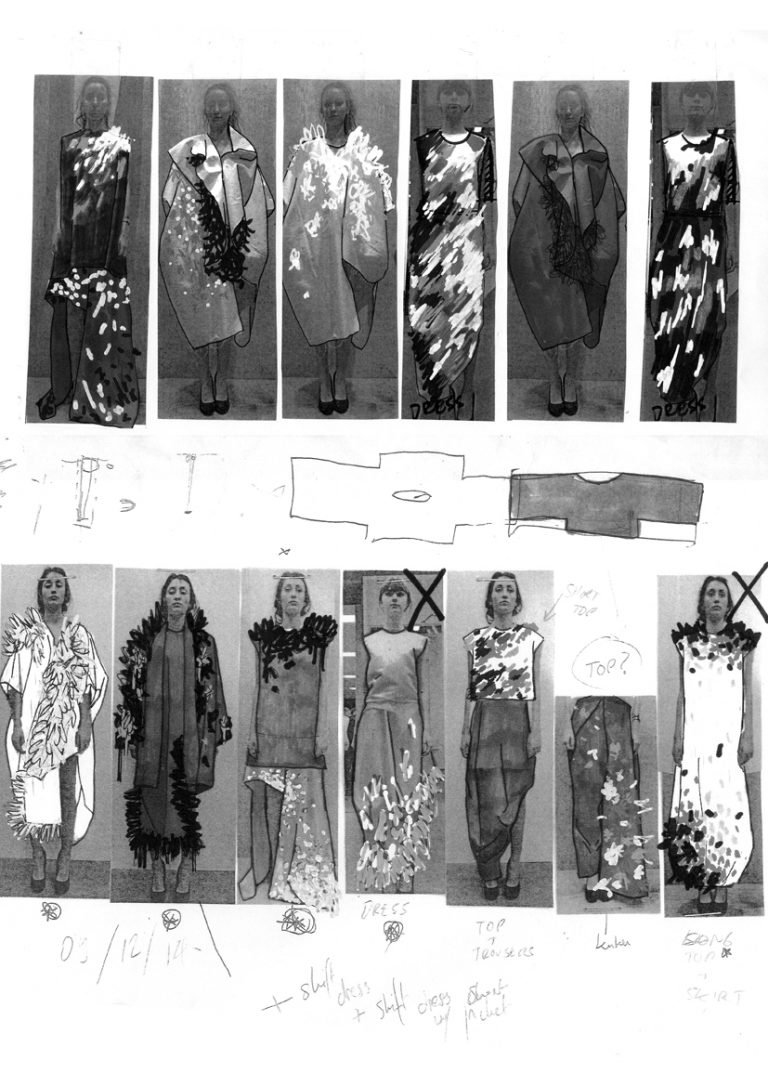

His understanding of 3D – both hard and soft – feeds into his designs: “I think I find the most interest in the shape of a garment, or its silhouette. I find that fabric gets in the way of me seeing this, if it’s overly printed or whatever. I’ve never liked anything because of the fabric, or because of what’s on the fabric,” he says. Looking past the dazzle or obtrusive color of a fabric, Wallace strives to find meaning in silhouette and form. His passion for making, his understanding of form in 3D, combined with his modest, quiet, thoughtful personality, make him a perfect modern craftsman; a 21st century heir to Gropius’ old ideal of an all-embracing work of art – a Gesamtkunstwerk – a foundation block of the Bauhaus school.

Wallace would have fit in perfectly among Gropius’ protégées, who were urged to delve into a wide variety of artistic and design media. Wallace even considered studying architecture after his foundation year in art, so it should be no surprise that his designs reflect the thin lines of the Hungarian-born Marcel Breuer or the self-taught French architect and designer Jean Prouvé.

Like these Modernists who reveled in calculated, controlled designs, Wallace seems to find comfort in problem-solving and constraints. He restricts himself to simple lines and understated textures to elicit an ideal truth. Wallace even says he enjoyed switching from womenswear to menswear before starting his MA: “I think there is a freedom in having those set of rules.”