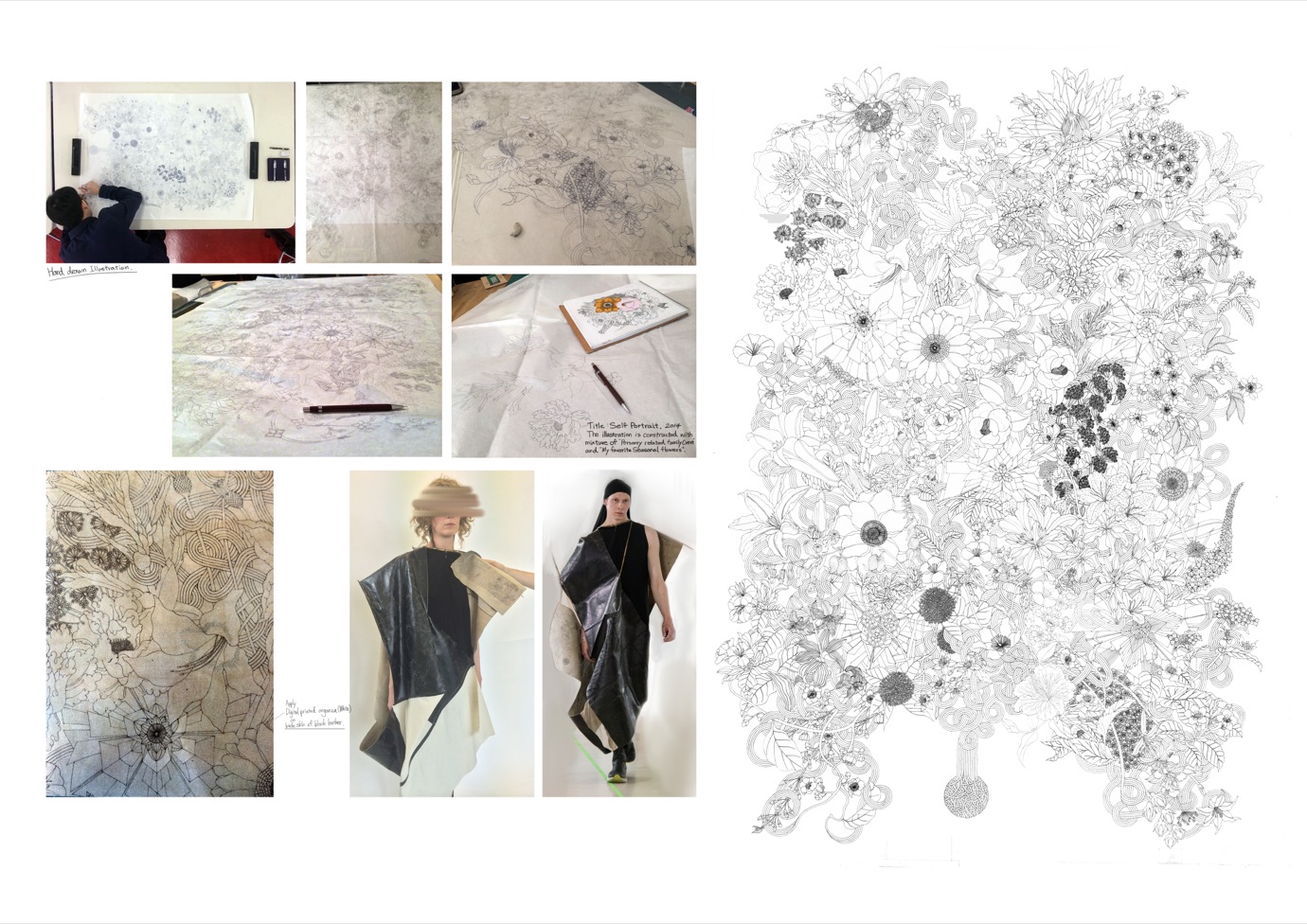

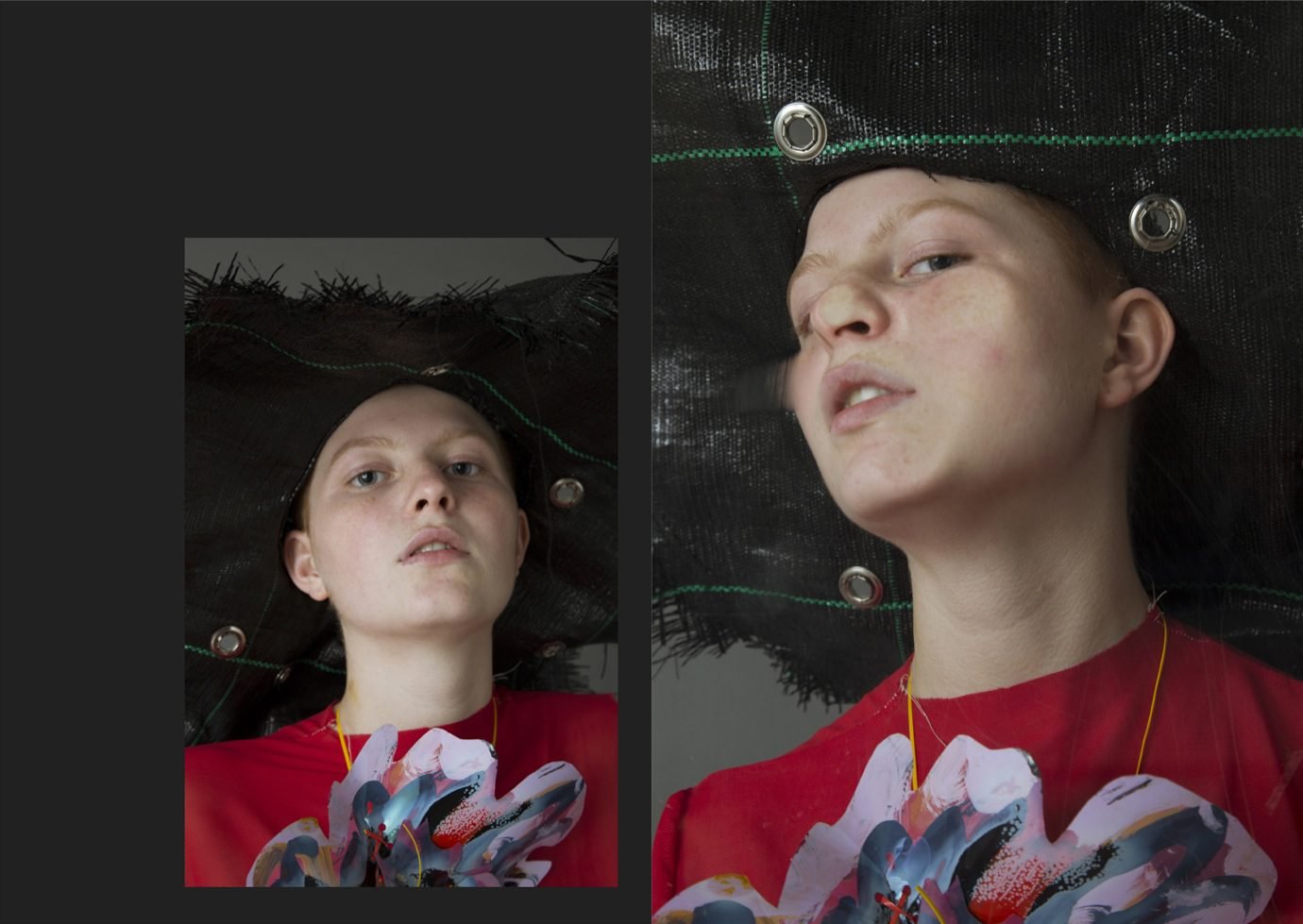

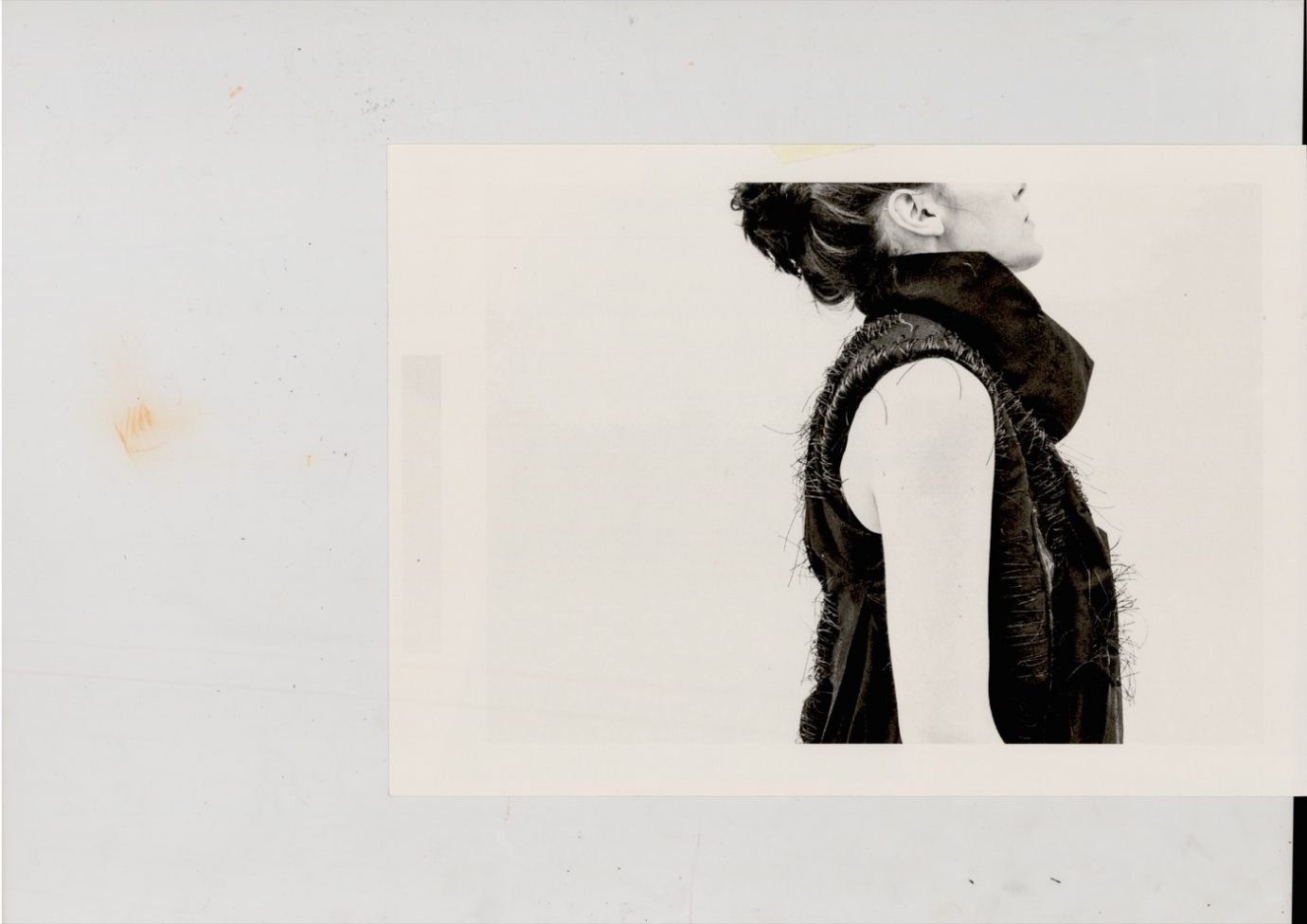

As we enter the studio where the video of his new “Purified Imperfect” collection is being shot – you can find a teaser here – the garments seem to come alive under the projection of Naoya’s intricate illustrations onto the models’ bodies. The team is international. The feel is professional, yet strangely festive. Did Naoya just create the ultimate party clothes? Models dance between each take to the original piece of electronic music made especially for the collection by a Japanese composer.

Now picture colourful LED lights running under the fabrics and the soles of futuristic trainers. It is minimalist, fresh and fun. It’s even comfortable! “I want my clothes to be enjoyed” insists Naoya. His fashion is indeed enjoyed in motion. And he creates each uncanny moving piece thanks to a unique, tirelessly refined experimental method.