“A lot of my work was linked to the fact that you can’t necessarily find your size in luxury fashion or if you find it on the high street, it’s just been graded up and hasn’t been designed specifically for the shape of your body. ” – Sinéad O’Dwyer

The philosophy behind your work is about creating a faithful representation of the female form and narrating the complexities around body image. While that exists throughout your work, how does this collection differ?

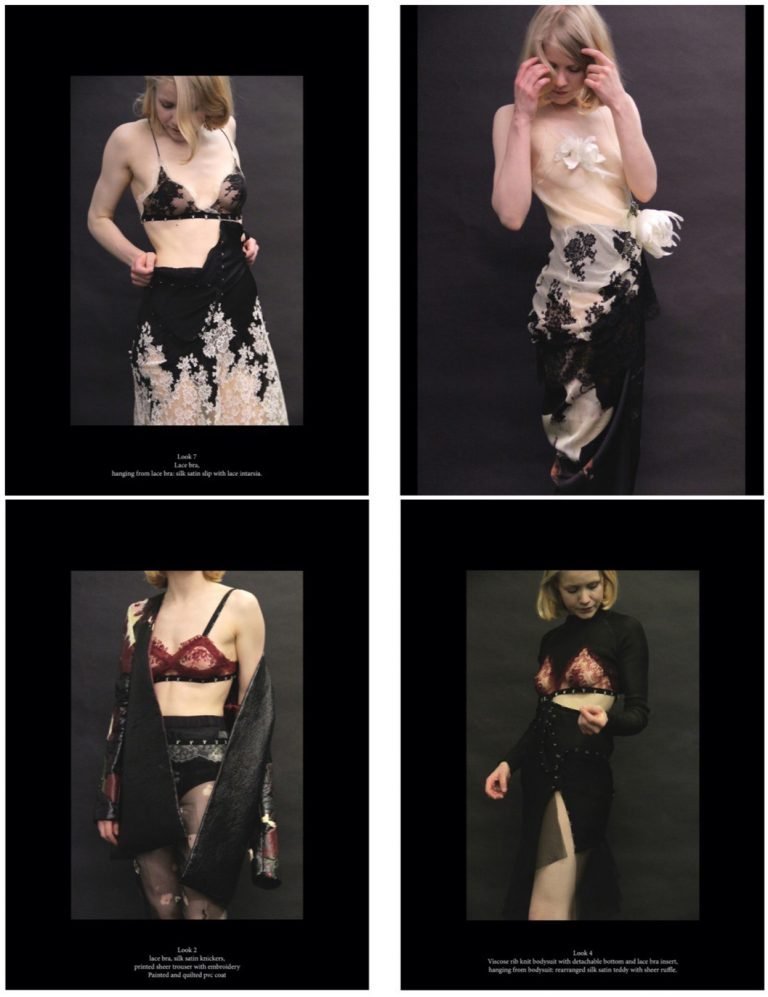

Before, I was really focused on showing how these curvier bodies are excluded in order to highlight how a lot of the issues in the garment industry are related to bad fit, exclusion, mental health, and dysmorphia. A lot of my work was linked to the fact that you can’t necessarily find your size in luxury fashion or if you find it on the high street, it’s just been graded up and hasn’t been designed specifically for the shape of your body. Everything has been super personal for me and I’m ok with slowly inching forward. The first collection was very much about conversations with people and my own experiences. This collection is about my own impressions and ideas of the edginess of the straight line and how you don’t always need to have something fitted in order to wear garments that cover up the chest more. It’s much more focused on the bust, a feeling that I was trying to express that I hadn’t seen before. For me, that was the new direction.

The design principle behind it is that I’m taking the bodies I was talking about before as the beginning of the design process, and opposed to designing something and then just making it fit. Jade is the initial model we used from the first collection and the body that I lifecast and these clothes have been designed for her body. It’s a continuation of it, but by looking at specific garments, as opposed to before when I was focusing on the bodies. Now, I’m looking more at archetypal garments and the styles or ways of dressing the shirt, the leather coat, the leather trousers, the thigh boots and picking out garments that are really difficult to find that fit you well. Especially leather garments. Real leather is more of an item that can be found in luxury fashion and if no buyers will buy bigger than a certain size, brands won’t make bigger than a size 12 and sometimes 14 or 16. If you have the money to spend on leather trousers, where are you going to buy them other than being made to measure? We wanted a really stunning super-high fitted boot that fit Jade to a tee. I just wanted to make a pair of trousers that fit her to perfection. Jade said to me, “I’ve never actually worn a leather trouser ever.” I think most women can relate to the thigh boots because it’s notoriously difficult to find the right size.

You often work with a muse or people that you know, how important is it to foster a sense of community in you when you’re working?

It just makes so much sense because people like Jade are the people I want to dress and also, I really trust her and respect her opinion. It’s funny because the first look we put together was one of her first shoots and my wife’s first shoot. I had difficulty with casting the other girls because there are way fewer curve models than there are sample-sized models and there’s a lot more, say, size 12 curve models. I also don’t like those labels, they’re stupid. But finding someone the exact same size and proportion as Jade so that I could easily fit the garments on was difficult. I loved working with Raphaela and it was nice to have more models on set but that’s something I’ll have to think about for next season. Do I want to have two different models so I can have more scope for the casting stage? I think before I wanted to make sure I was representing all sizes but that’s really difficult. So I think each season I’ll add one new proportion, one new size.