Nathan was born in Chicago, but grew up in Hong Kong, only to return to the States for boarding school during high school years. From an early age, he was passionate about drawing and illustration, and when discovering fashion aged 16, he returned to Hong Kong to do a more suitable art program to work on his portfolio. He was finally admitted at Central Saint Martin’s foundation course, and later, Fashion Design with Marketing.

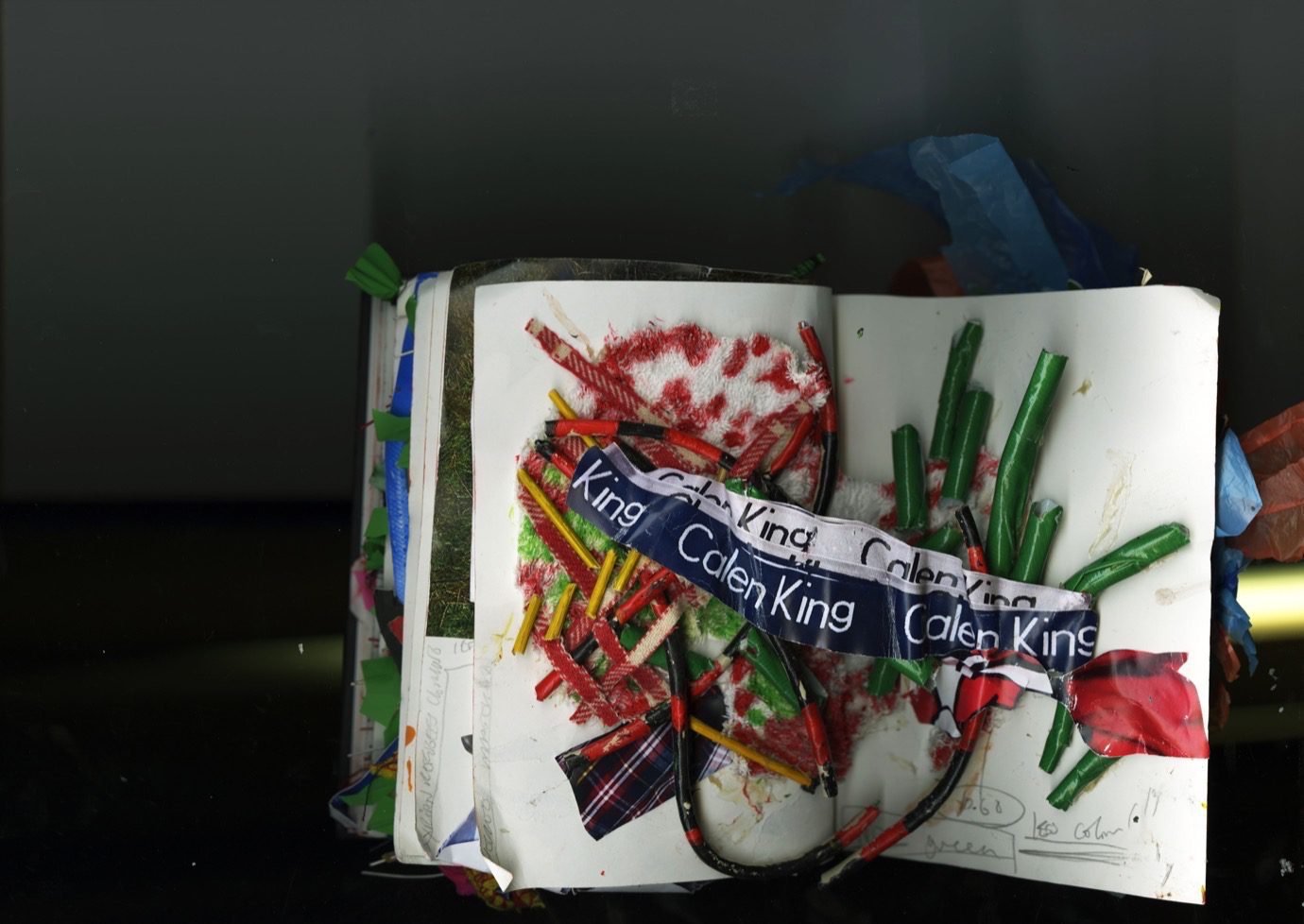

Besides the sewn garment, Nathan particularly loves expressing himself through photography, “particularly with film since I lean more towards the low fidelity side on the aesthetic spectrum,” he comments. “But my favorite creative expression is any form of illustration, even digital; sadly I don’t get much time these days to just sit and draw.”

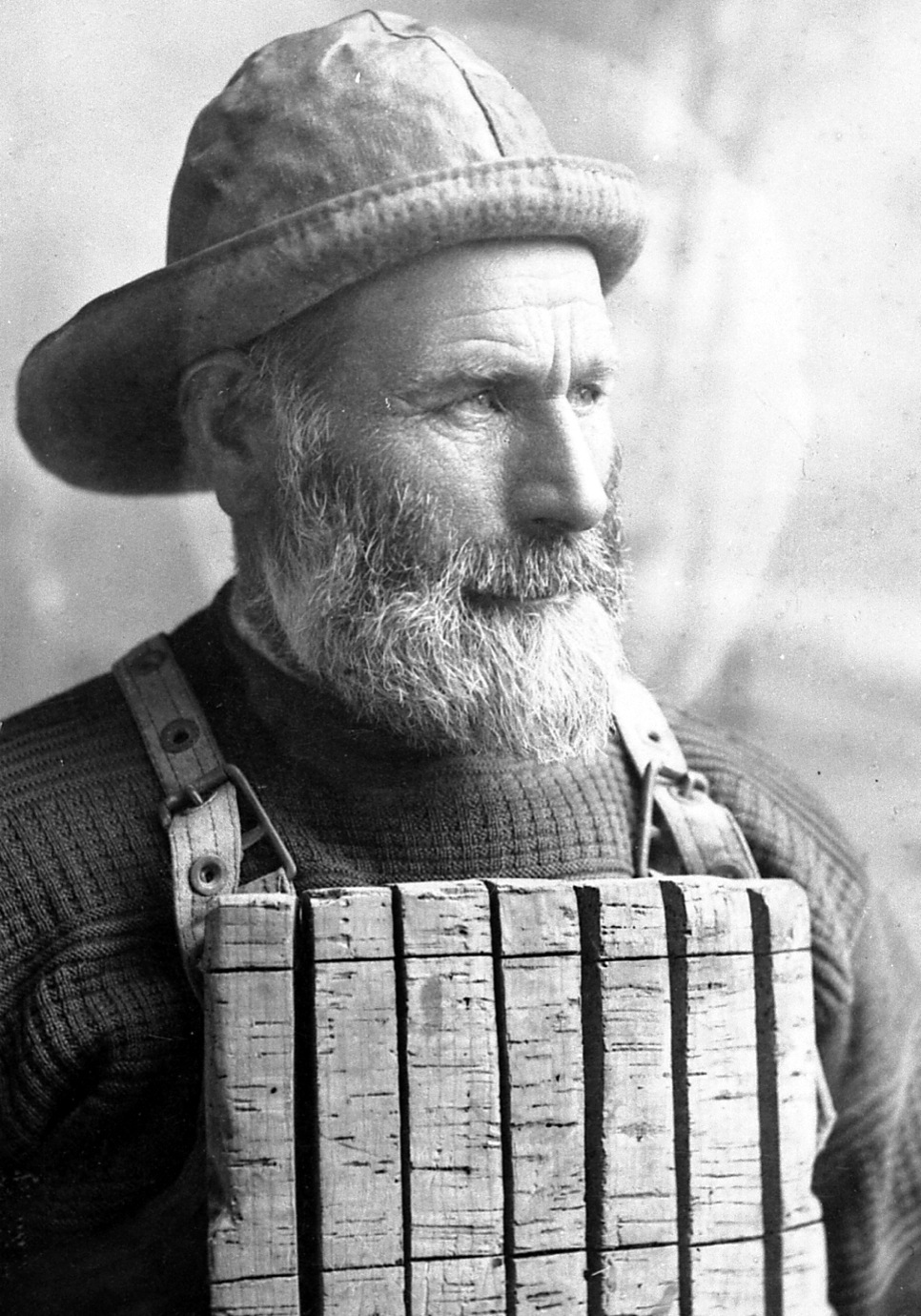

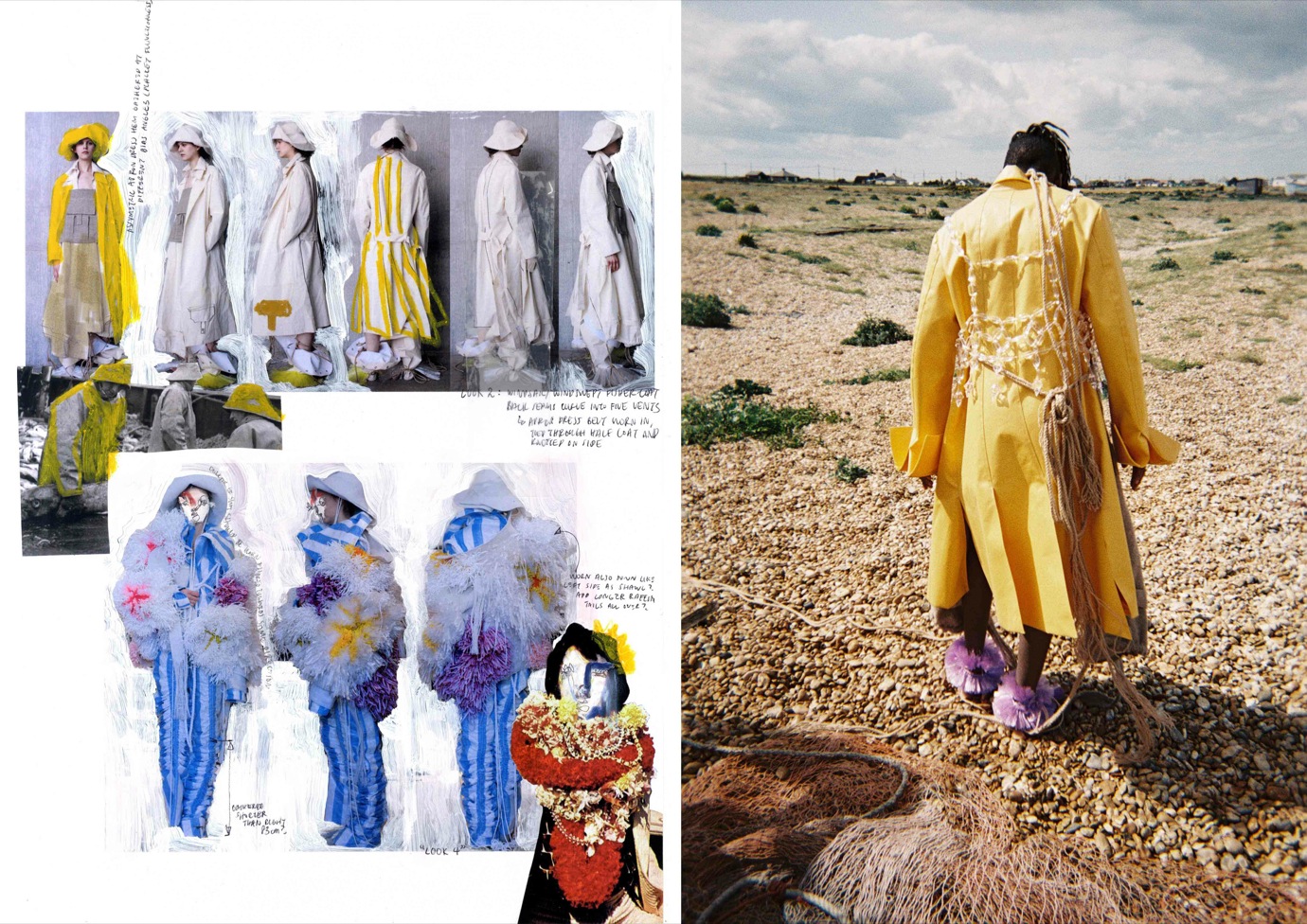

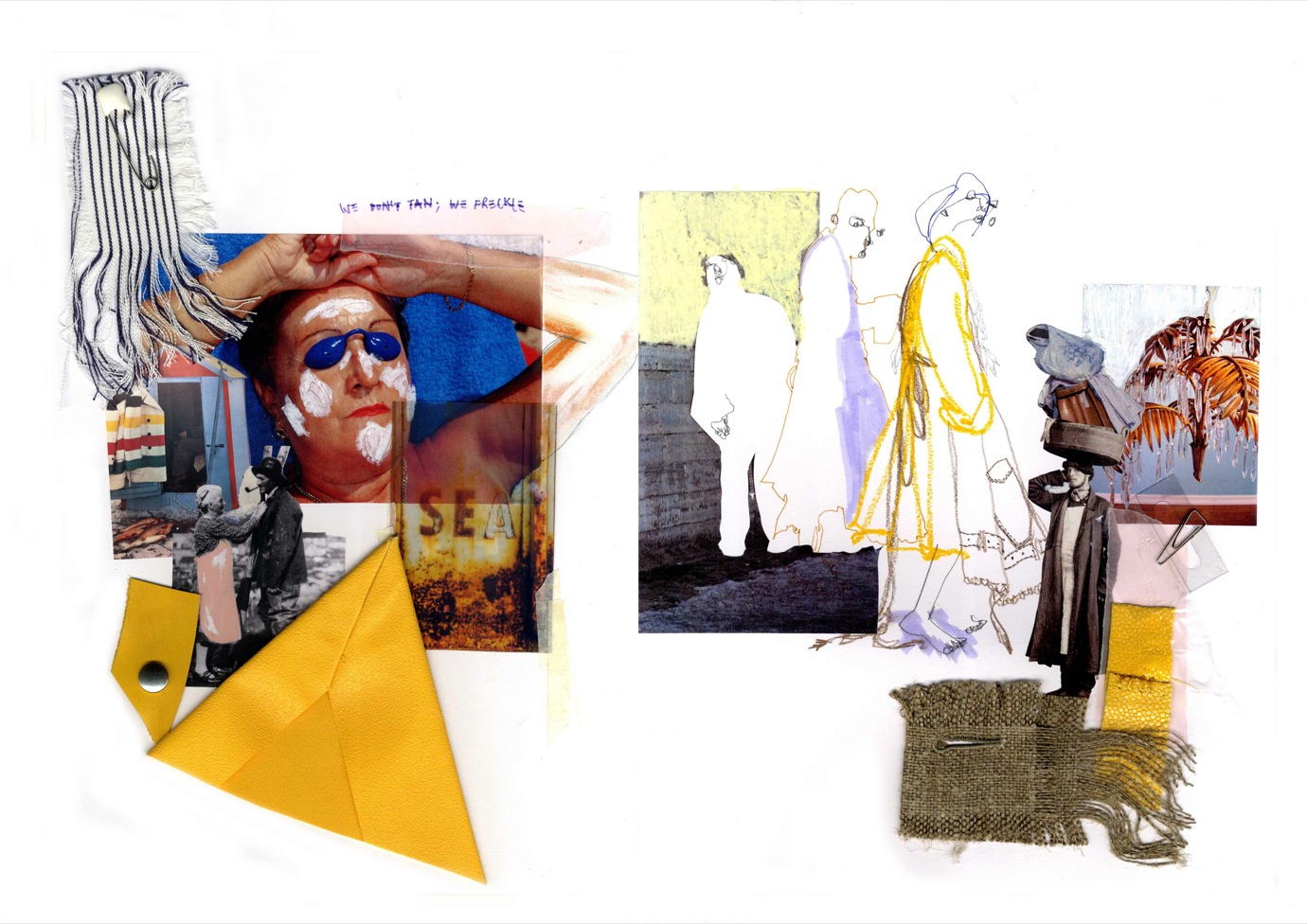

Nathan’s graduate collection took coastal life as a starting point, and his girls can best be described as a kind of aestheticised, industrialised mermaid stranded on the beach in 2015, caught and adorned in the waste products of industrial fishing. For his initial research, he gathered historical images of English and Guernsey fishermen in their work attire, amalgamating it with references to Hawaiian traditional clothing as well as ‘50s surfing culture, seeking “to bridge the gap between business and pleasure,” he explains.

“I HAD THIS IDEA OF A GIRL WITH HOARDING TENDENCIES WHO TRAVELED BY A FISHING-TRAWLER SHIP TO HAWAII IN THE FIFTIES, NICKING BIKINIS AND SARONGS ON THE BEACH, GETTING LOCKED-IN AT A NIGHTCLUB SO SHE YANKS DOWN THE CHANDELIERS AND FASHIONS THEM INTO CLOTHING, AND SCURRIES OFF WITH HER ISLAND REMNANTS FROM SHORE BACK TO SHIP.”