Before entering fashion education, Rozalina was in a very different field of knowledge, as she studied Political Science in her native Bulgaria. To her, fashion was a strong interest, but as she had never been drawing or sewing, it seemed to her unrealistic to pursue it further. “However, I just kept thinking ‘this can be an actual profession? why wouldn’t everyone want to do that? It sounds like so much fun!’” she explains over e-mail. She began doing research into fashion colleges, which naturally led her to Central Saint Martin’s application process. “I dropped out of Political Science, drew, drew, drew, and there you go. It turned out to be a pretty tough world.”

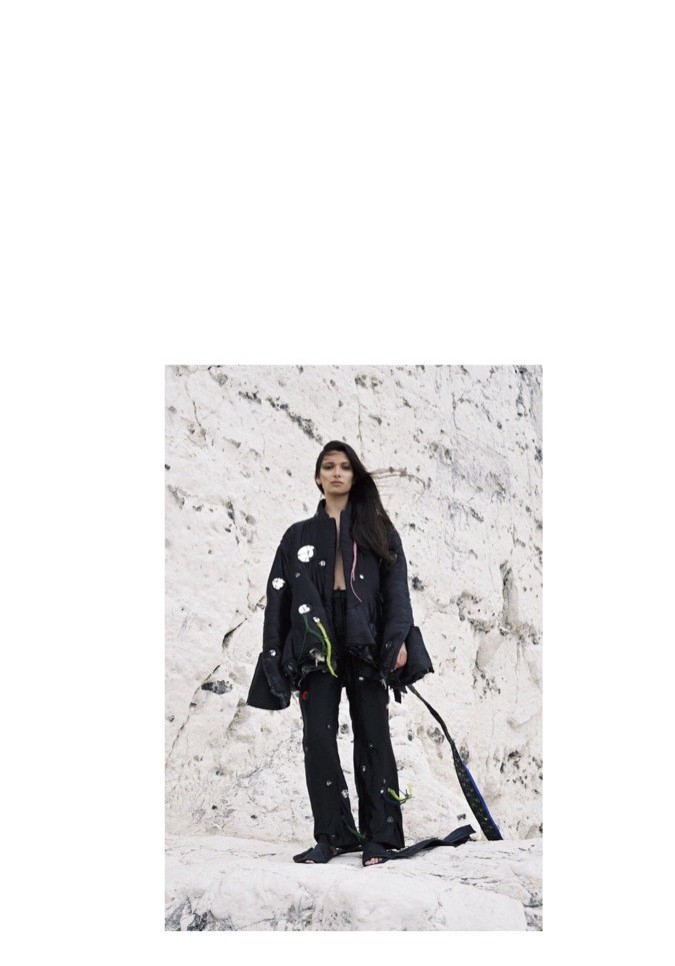

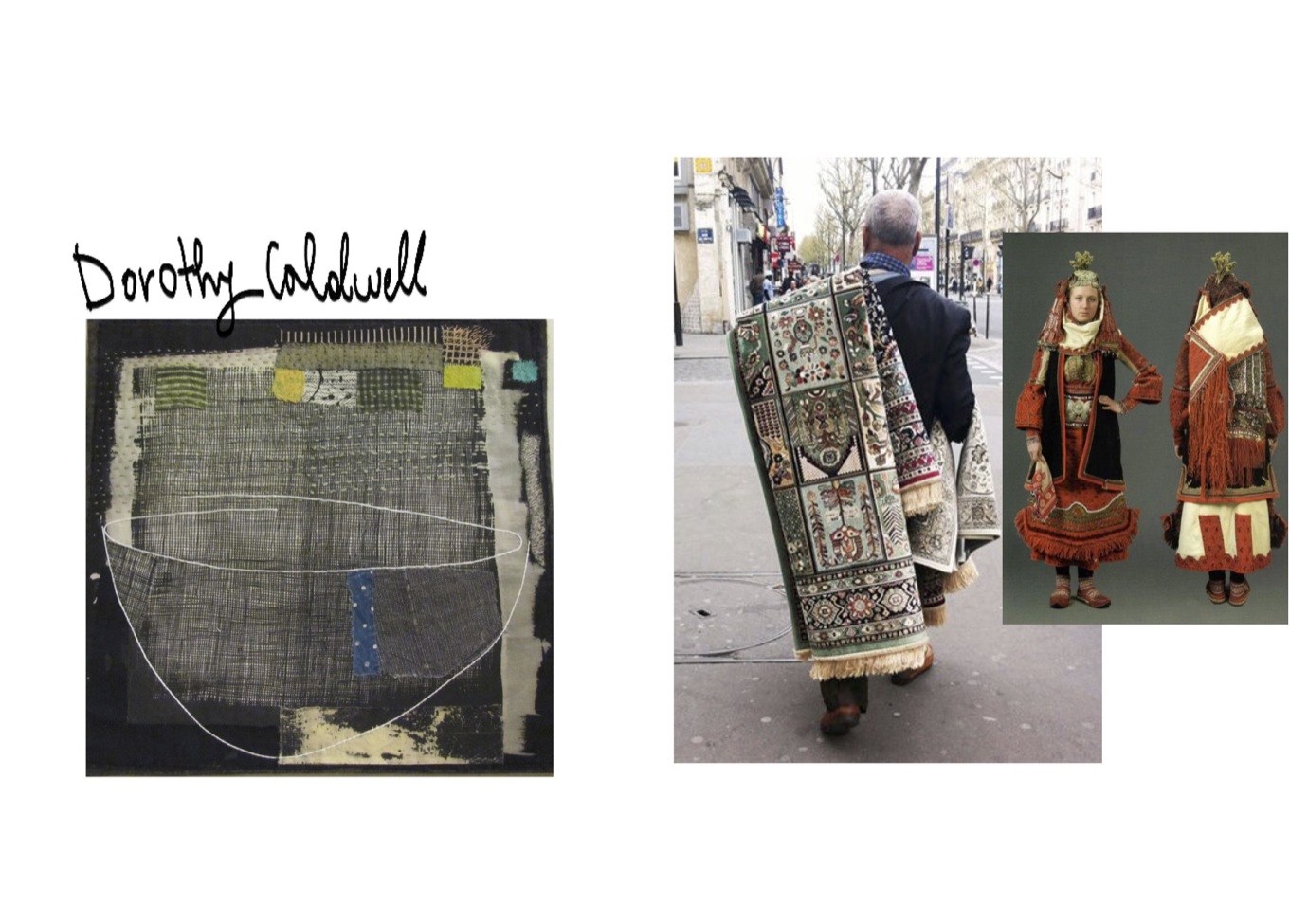

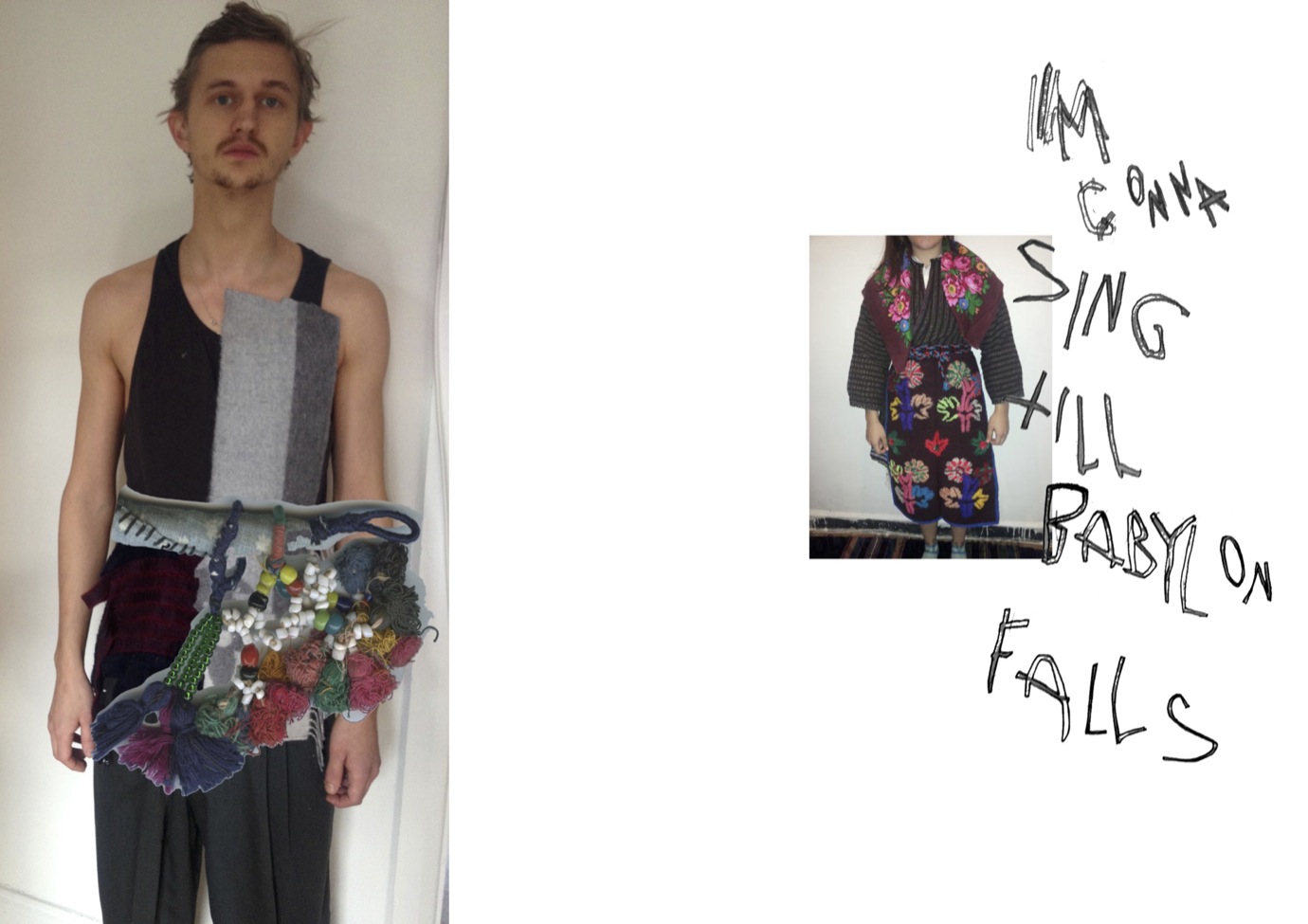

While at college, Rozalina began exploring her roots and heavily researching into Bulgarian folk wear, which she had been amazed by since childhood for its richness in detail. Its folkloric history led her to a new interest and appreciation for incredible craftsmanship and care for each garment. “The attitude in garment making back then was ‘okay, this silk jacket will stay with me or with my son/daughter for the rest of their lives, so I’m going to put all my skill and love into making it’”, she tells us. “Things were made painfully slowly and made to last, and you can see it in the pieces.” Travelling through Bulgaria, she encountered neatly ornamented 19th century garments, hand quilting, metal embroidery, crochet lace, which she visibly integrated in to her graduate collection. “For one’s final collection, I think it’s really important to use references that you have a relation to,” she says of her passion for Bulgarian folk wear. “It wasn’t so much about the actual look of folk wear, but about finding similarly labor-intensive processes and re-experiencing the making of them.”

“MY PROCESS TAKES AGES, BUT THAT’S ALSO KIND OF THE POINT.”