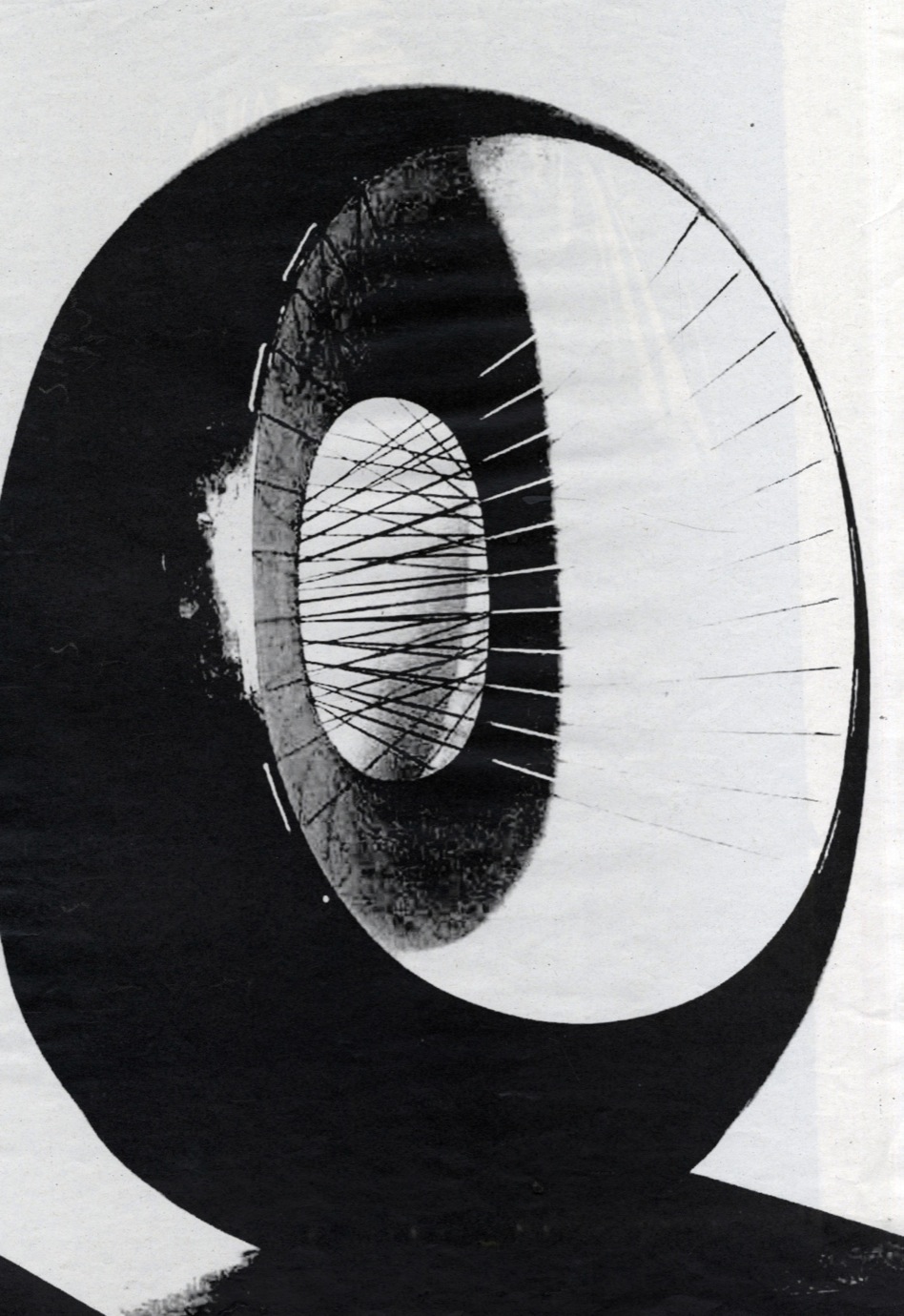

For her final collection, the main focus was on Barbara Hepworth and the way her work reflects on human relationships. The English artist juxtaposes materials and shapes to symbolise the tensions between different people – a woman and a man, or a parent and his child. A central image in Lynne’s research was a picture of Hepworth’s totems in the Yorkshire Sculpture Park. The industrial, heavy objects contrast sharply with the blowing grass and trees.

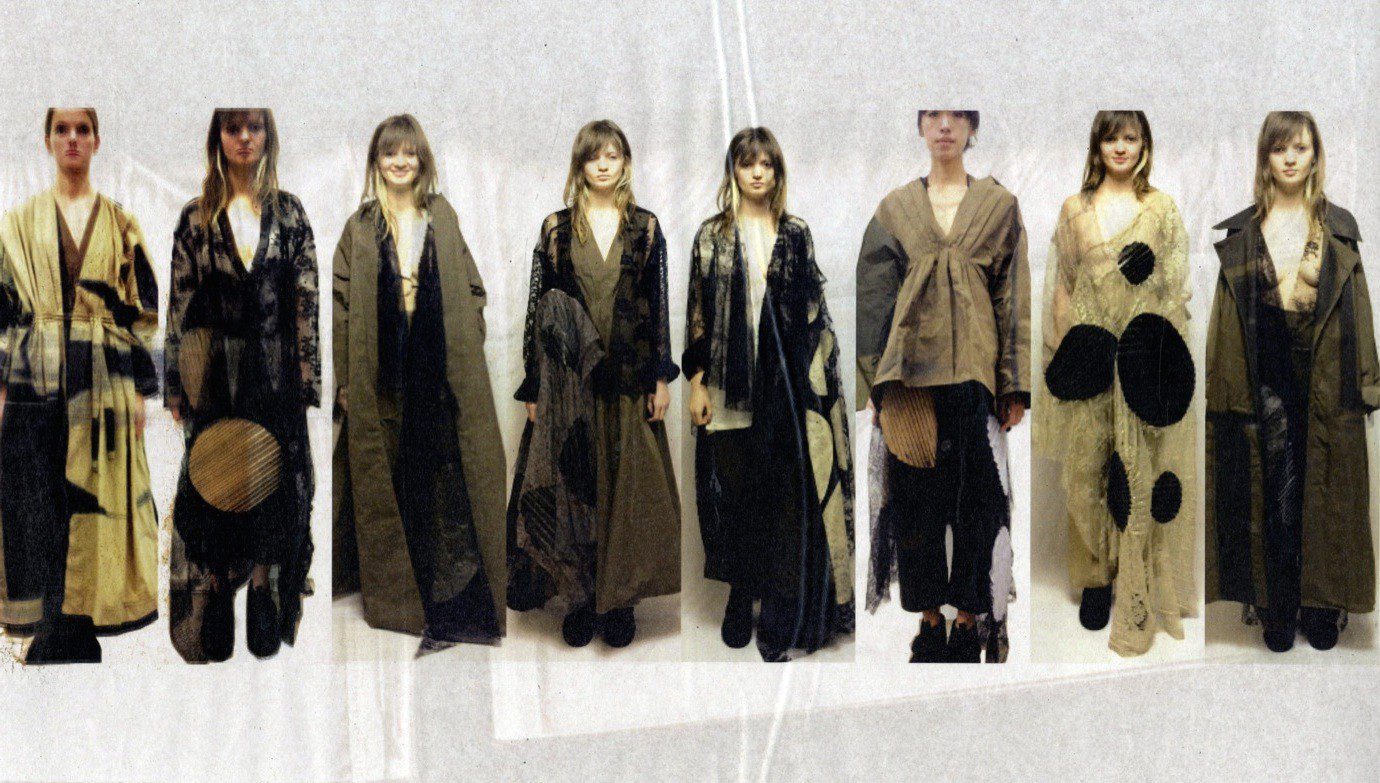

Lynne has worked on the same concept of tension throughout her design process. “With my collection, I knew I didn’t want one print across eight looks, I wanted a mix that was more dynamic.” She achieved this by combining nylon – heat-pressed to make it paper-like and crunchier – with a flowy and feminine lace.

You can zoom-in endlessly on Lynne’s creations and find the idea of contrast on every level of her collection. From afar, the clash between the practical nylon and the decorative lace is immediately palpable. In detail, one notices the flat-felled seams (commonly seen on denim) structuring the soft lace.

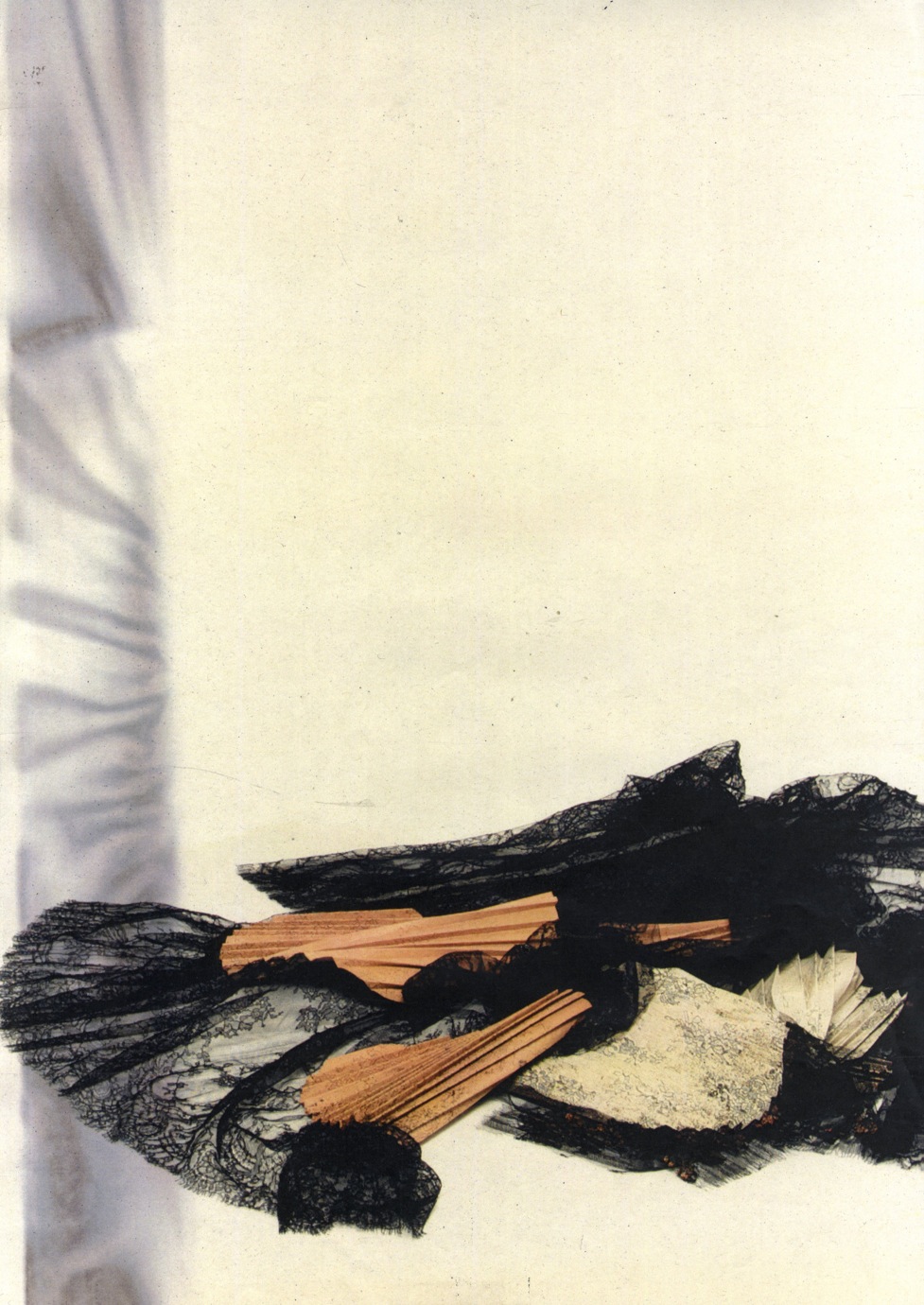

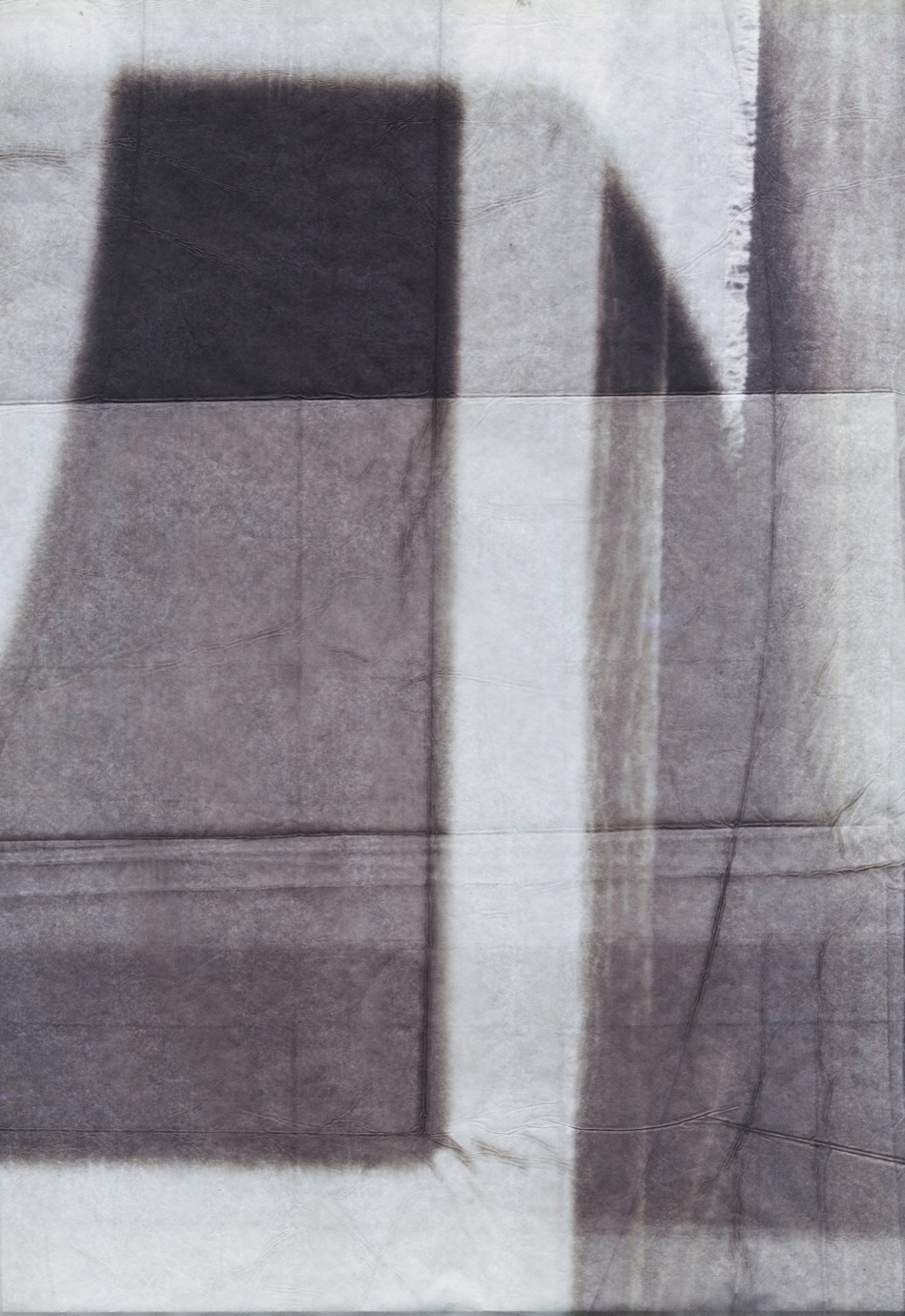

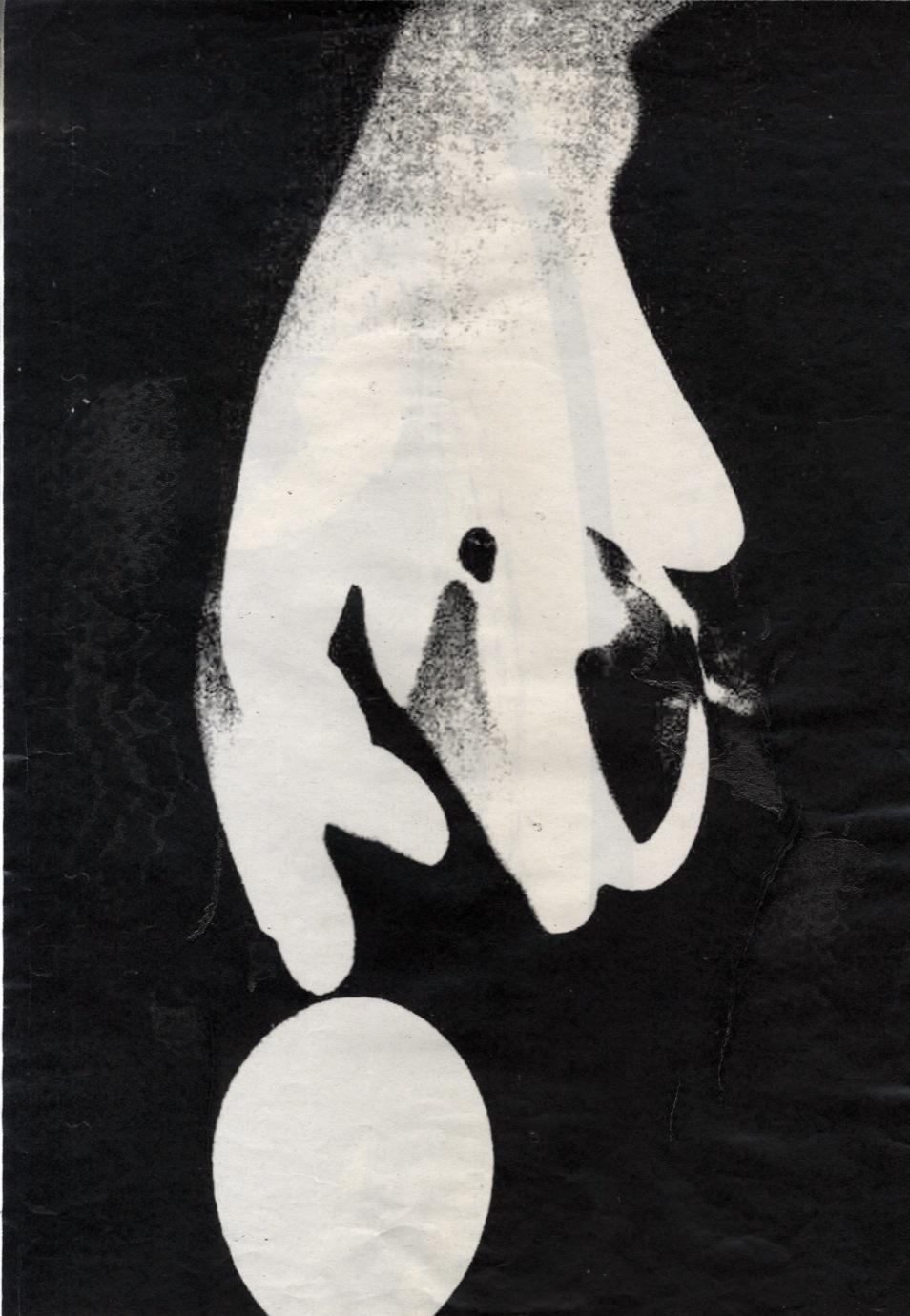

On the nylon, Lynne used a heatpress to print contrasting geometric shapes next to each other. Each print is unique, because the heat would react differently to the shapes each time. With the lace, she broke its meticulous pattern by adding simple vinyl circles. Then she pleated and pressed the samples, pressing the motif of the lace through the vinyl. This makes the dresses almost sculptural. The decorative fabric isn’t something she would’ve naturally chosen, but when she got it sponsored by Sophie Hallette, she felt challenged to take it away from what lace is usually associated with.

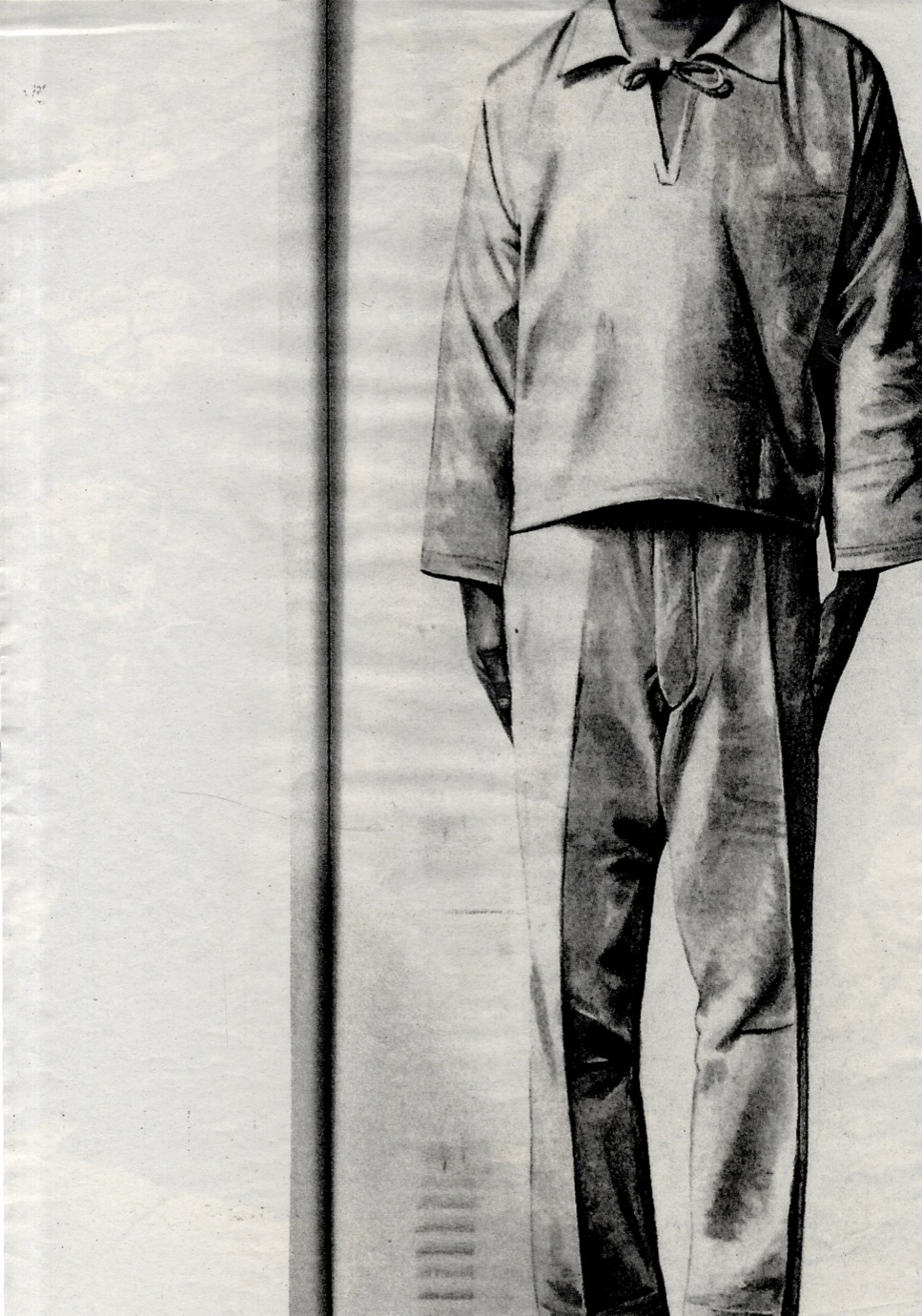

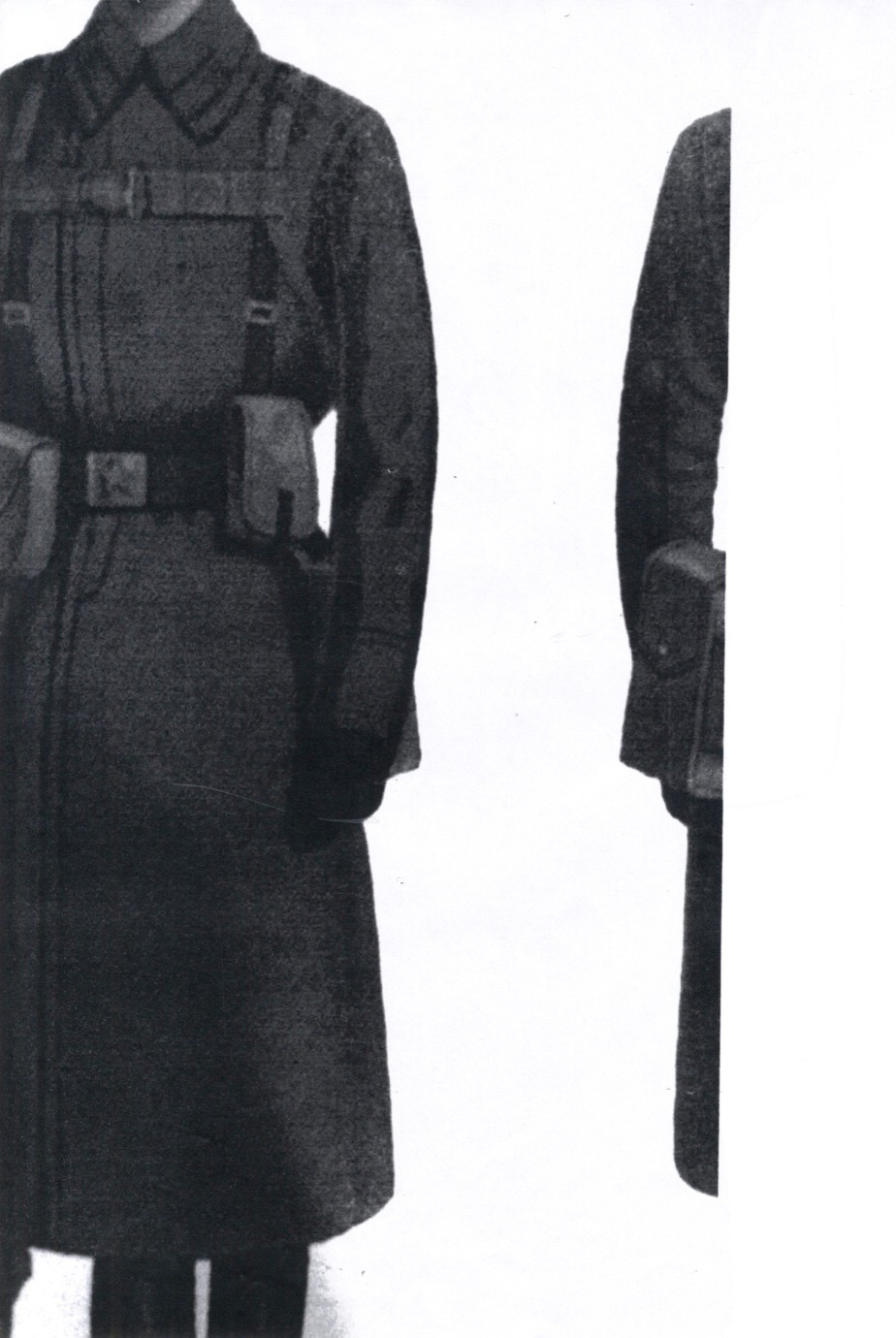

In the styling of the silhouettes, Lynne looked for an opposition between military and sensual. In this perspective, it was great to have a team who worked on the garments: “Some of them looked at the feminine silhouette, others looked at the military. So again, there was a mixture. That worked really well.”

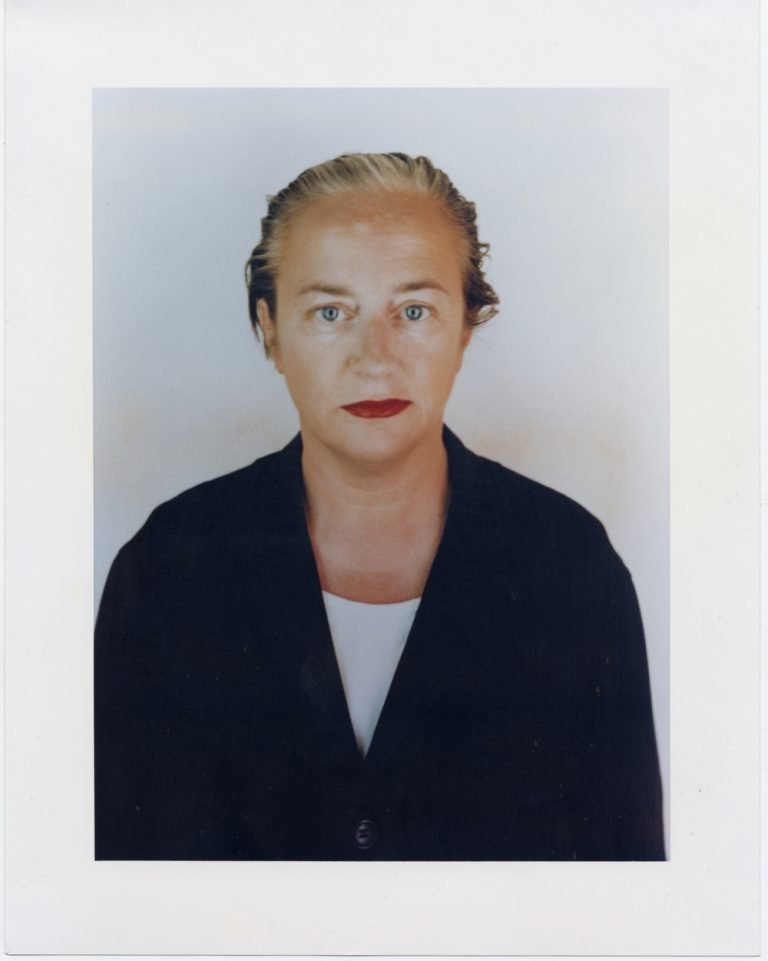

Lynne loves working in a team and being able to bounce ideas off other people. “I am not someone who wants all the glory to myself.” With the help of her team, making the collection became an amazing experience. “I’m so happy to have had my team, they really had my back. Like I had my own support system.”