“THE MOST DIFFICULT THING IS NOT THE PATTERN MAKING; IT IS TO SEW. WE HAVE A VERY HIGH LEVEL OF QUALITY HERE. WHATEVER THEY DO, EVEN IF IT’S GRUNGE, IT HAS TO BE WELL DONE.”

Are the courses still focused mainly on the technical making of the garments?

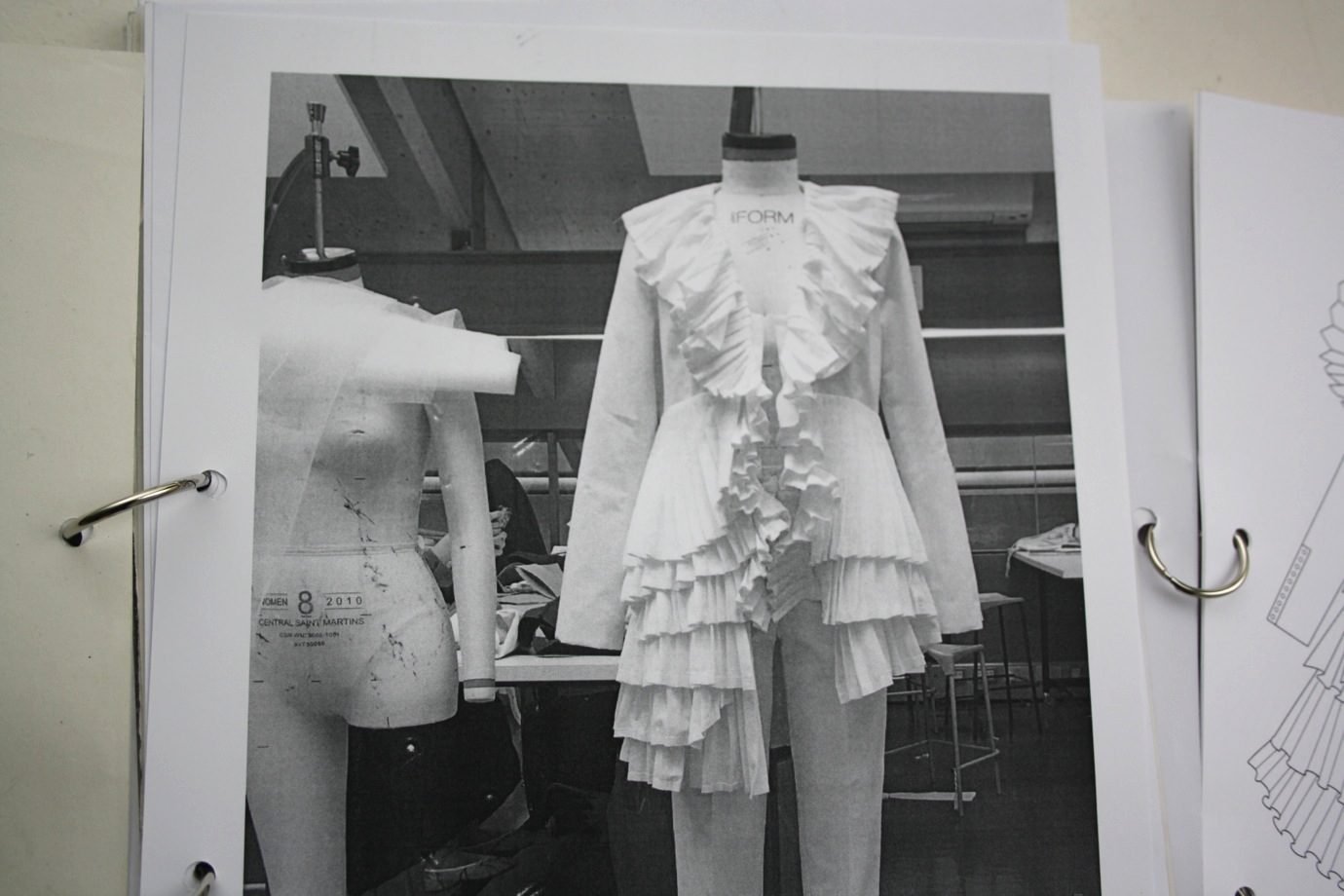

It is not that you just learn technical skills. First, you have fabrics: which types, what colours, and all those things. You are going to learn how to ‘do’ a dress, or a blouse, or pants — which will be very technical and in depth. From the third year, you can decide what you want to do: work in a workshop, in an atelier and become a pattern maker, toiliste, modelist, or to go and be a designer. Then the students start to work on the processes to become a designer: ideas and images, doing three-dimensional research…

So is it in the final year when students decide what they want to do?

At the moment, they start to decide from the fourth year, but they are going to start making that decision from the third year in the future. Because we have changed a lot of things here in the way that we teach technical skills. Usually, when you leave school, you are not professional. But the way we teach it, when you finish the course here, you are quite a good modelist already – you are not like a junior leaving school. You are a bit more than that, because you have spent four years learning technical skills.

How does the process work in terms of the students’ relationships with their tutors?

The further along they get, the less the tutors help them. When they do their final projects, the students should decide what they are going to do regarding their level of technical skill. This is sometimes difficult, because some are better than others. For this, they need help, because sometimes what they want to show is quite difficult. So for this they have advice, but no one ever makes things for you — that is a bit forbidden here. Whatever is the student’s style, at one point they will have to do things by themselves. The most difficult thing is not the pattern making; it is to sew. We have a very high level of quality here. Whatever they do, even if it’s grunge, it has to be well done. They can’t make something that looks like it’s done by the high street!

So this fourth year only came into existence in 2010, is that correct? And it was set up by you and Stéphane Wargnier?

We started it because originally the students only studied here for three years. But almost all other schools do four or five years. We realised, because we work for fashion companies, that usually when you leave school, you are so young, and you don’t always know how a company works. The students need to know why the commercial department speaks with the merchandising department, who speaks with the designers, who speaks with the communication team – and finally that all those people work together quite often. We realised that quite a lot of the time, they have no idea that it is not going to be creation all day long, so we added this fourth year. Every week they have people coming from French fashion companies: they can be CEOs, designers, production managers, merchandising managers, anything. They come and explain their work and how they decided to do this after their design studies. Sometimes for students, it is a way to discover that you have other types of jobs, which are not so clearly taught in school, but which can be very interesting; for example being a production manager or product developer. Often companies have previously hired people from business schools for these jobs, but now they’ve realised it might be easier to hire people from a more fashion-oriented background.