At Westminster, they don’t have pathways within Fashion Design. No menswear, womenswear, sportswear, or print. A student is pretty much free to do whatever he wants to do, and only narrows down his choices during the final year. Why? According to Andrew, “If you’re a good designer, you should be able to design menswear, womenswear and accessories. Good research is good research. Good design development is good design development. The point when you’re turning that into a product is where you think, ‘actually, this is more menswear’. So they can specialise.”

Maybe it’s difficult for a nineteen-year-old to immediately pin down what specific pathway to choose when he/she applies to study fashion design, but perhaps it’s also questionable whether teenagers should be expected to immediately continue studying after they finish high school, or their A-levels. Andrew agrees, and thinks that the depressing thing is that students have already mapped out a career path, where one starts with foundation, goes on to do a BA, and when they’re asked “when you leave here in three or four years, what will you do?”, they answer with “Oh, I want to do an MA.” He finds it questionable. “I think they’ve been fed this idea that they can’t just go into the industry; they don’t feel they can just do an apprenticeship at 17 or 18, nor do they feel that they are done after a BA. They think ‘I must do an MA’.”

Why did you choose to do an MA yourself?

I wanted to use the print room! When Louise interviewed me, she said “you’re just fucking coming in to use the print room for Lee [McQueen]! You’re doing Lee’s printing!”

Were you?

I was doing it for him, me, everyone. I remember, one day, I got caught at lunchtime. I was screen printing about a hundred Playboy t-shirts — trying to do them really quickly. Natalie [Gibson, print tutor] caught me, I was like “hi?”.

She didn’t make a big fuss out of it?

No, she just laughed, I think she thought it was funny that I was rushing to get all this stuff done.

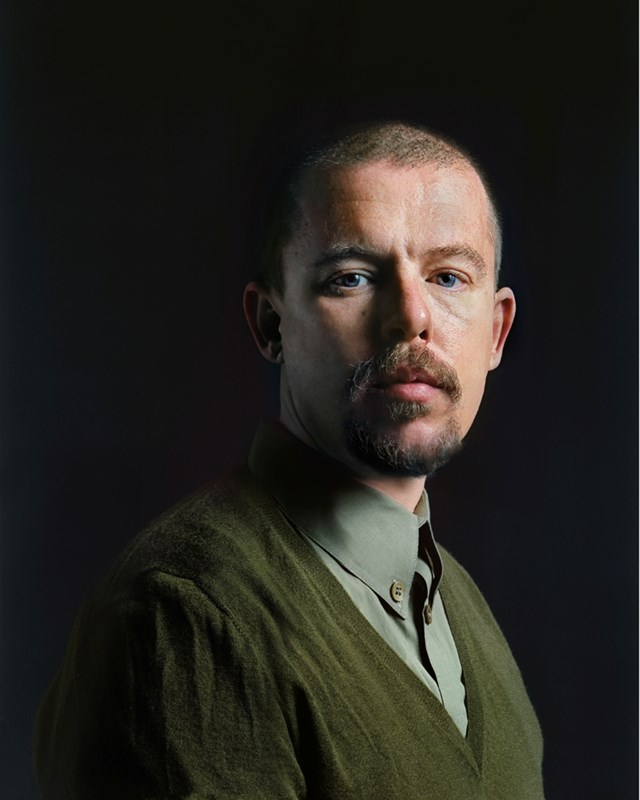

At that time, when you were doing your MA, were you already assisting Lee McQueen?

Back then, I don’t think it was so professionalised. Lots of people were doing lots of things. I was making clothes and selling them in shops; there were people like David Kappo, and Tristan Webber… There were just lots of people who were going to St Martins and made stuff. Still to this day, I never know who was actually on the course, and who was just going there to use the machines. There were people, who I’ve since realised, never ‘studied’ there, but they were always in there, making stuff. It wasn’t like, “do this course because you can then do the MA and go on to work there.” It wasn’t like a career path. It was just somewhere you could go, I guess.

One of my main memories is that we’d all been out all night, got drunk, and stayed up all night. We went straight from some dive bar to college, at 9 o’clock in the morning, still obviously drunk. We started making stuff, then there was a bomb scare at Charing Cross Road. But they couldn’t send us home; they had to seal the whole building. Most of the class was there, really drunk, wondering “how do we get home?”

“Couture feels dead again, because it’s become another collection, like RTW. It has lost its sense of spectacle or its sense of being a laboratory to push ideas forward.”

Do you think your creative process is better or worse when you’re drunk?

I think you think you’ve got better ideas. It depends where you are though.

Are your surroundings a really big influence?

Most of the times, everyone would go down to Compton’s. There were mostly other people from the college, and you would be chatting about creative things, or you’d say, “have you seen the Gaultier show?” or whatever. So, actually, you were talking to other creative people. I think that helped. Also, nobody was really worried about what their marks were. I don’t know what it’s like now, but I can’t remember ever getting a mark for anything.

What is the most important thing that you teach your students?

I suppose most of what I’m trying to teach them, is to get them into a process of being creative. It doesn’t matter what their process is, and there’s no correct way of doing it. It’s about finding the right process for yourself.

I’m going to have one of those Louise rants: at the moment I’ve got a real problem that everyone thinks the solution is LVMH. In the 90s, this idea was created of what ‘a successful designer’ is, which is to be part of a huge conglomerate; that designers want to be bought up by or work for. They want to be part of this huge process. It baffles me that students don’t think, “well, actually, I can just do it on my own, I don’t need to be part of that world.” Especially when you think of all the designers who have worked there, and the realisation of what that actually involves. If you look at Galliano, in terms of how he’s come out of that, and how he was treated, you just think, “well is that really something you want to be part of?”

“They’re very rare, the Gallianos and McQueens. Once every twenty years.”

It seems to become very corporate when you have to comply with their rules, and deal with the pressure.

But really, I think the students have almost become corporate before they’ve even got there, because they feel that that’s the only right answer. You think, “well it isn’t, at the moment, fashion is just going through that period.” It’s a bit like in the beginning of the 90s, when everyone was saying that couture was dead. ”Who wants to go to the couture shows?” Then suddenly, it was revived in the mid 90s. Now, couture feels dead again, because it’s become another collection, like RTW. It’s lost its sense of spectacle or its sense of being a laboratory to push ideas forwards.

We were all discussing the shows, and there’s been nothing that has excited us. We were playing the game of “who needs to be sacked?” and “who should actually be doing those jobs?” The idea that Galliano is going to Margiela is ridiculous.

He had said that he hasn’t produced his best collection yet.

Well they’re not going to be at Margiela, are they? His best collections should be under John Galliano. Even if he hasn’t got the rights to that name, he should just do it as himself, if he feels so strongly about retaining that creative drive. You’d have thought he would have learnt from all those things that have happened. He needs to be his own man; not be attached to a huge company that has lots of other things going on. The designer isn’t that important in those sort of places. They’re just a hamster in a wheel.

It’s a rat race, isn’t it? And students look up to designers like J.W. Anderson and Christopher Kane, who have just joined these massive companies — everything seems to be going well with them, they’re getting their own store and have a lot of support.

Well, I’m hoping that people soon see through that. They’re very rare, the Gallianos and McQueens. Once every twenty years. Otherwise it’s the same old tired story, because every designer is chasing the same story. They’re all showing their wonderfully commercial selling range on the runway. I was saying to a student the other day, “why would you even bother getting on the Eurostar to see any of that?” You can see it in the selling range, you can see it online. What is it actually adding to the discourse of fashion?

“We always saw the fashion show as there being no point in dragging people to a show, unless you give them a show. If they want to see the clothes, they can just go to the studio. If you want them to see a show, aren’t you going to try to get them into your world — or some sort of world — so they have a reaction?”

Do you think designers aren’t really taking risks anymore, because (if you think about being a student) there’s a lot of pressure to sell, and otherwise you’ll be a goner after graduation. Do you think that people are scared to do what they really want?

Exactly, they’re scared. Also, I think there’s a huge skills gap. Regardless of whether we like collections or don’t like collections, we see collections where there’s no idea of how to drape or how to tailor a jacket correctly. Sometimes I look at shows and think they purposely haven’t ventured into areas, because obviously no one can do it. That’s really worrying. Once you start losing those technical skills, there’s no one to teach the next generation how to do those things.

Then things get lost.

Yes.

Then 3D printing takes over.

Yes, and then everyone thinks it’s all about laser cutting.

What do you think about laser cutting?

I think I get sick of it, like digital printing. I just think it’s a tool, like anything’s a tool. The creative bit is how you use any tool to make something that’s amazing. I make it sound like it’s all very depressing.

I guess fashion is depressing yet fantastic at the same time.

The secret, is the thing that people like Galliano managed to do: to weave that line between being really really creative and being really really commercial. It is possible. You can do both and you should be able to do both. Fashion, when it gets down to being just commercial, becomes very un-engaging. When you look at clothes, you think they have to engage in some way — whether it’s the quality, the fabrication, cut, colour, or print. Because, otherwise, why do we need more clothes? We don’t.

When you designed for your own label, how much of your catwalk pieces would end up being completely sellable?

I didn’t sell anything from the graduate collection, but from my first collection — the show was in Victoria Bus Station — I sold loads to a Japanese company. We just made the prices up on the spot, “£750!” Again, it was this whole thing of coming from nothing. It wasn’t about being about a business. I’m not saying that’s good, I’m just saying that’s how it was.

Both McQueen and I were influenced by the same designers, which were 80s designers like Galliano, Moschino and Gaultier. I think we always saw the fashion show as there being no point in dragging people to a show, unless you give them a show. If they want to see the clothes, they can just go to the studio. If you want them to see a show, aren’t you going to try to get them into your world — or some sort of world — so they have a reaction?

Both Lee and I worked in the theatre. We worked on Miss Saigon, and I also worked with the Royal Shakespeare company. I was totally at home with this idea that a show could be theatrical; it wasn’t necessarily about coming out with a nice feeling. I always feel like that when I come out of the theatre — it isn’t just about a musical. You can see a tragedy, or a comedy, a modernist play, or Greek theatre. It could be lots of different things. At the time, lots of people were pushing fashion in different directions. I think it was Hussein [Chalayan] who had that show where the models were wearing the Hijab…

“Spending £1 million on flowers [at Dior] is like someone saying, “I put £1 million of Swarovski crystals on a dress” — it becomes meaningless. Does that make the dress better in terms of its design or not?”

And some weren’t wearing anything at all.

Completely nude. It was the same season as my first season, where Georgina Cooper, who was one of my models, was coming out and her dress was full of flies. That was the very next day after Hussein, so I think we were all really pushing the idea that the show wasn’t all about selling clothes.

Why do you think it was then in particular?

I think because we all grew up in the era of punk, where fashion wasn’t about commerce. We all saw clothes as being a means to communicate ideas. I think that’s what we had learnt at St Martins as well. If we weren’t learning it at St Martins, we were drawn there because there were other people who thought the same as we did. We weren’t thinking about the idea of french seams, or an overlocker — it was about ideas.

It’s what they’re still saying at St Martins.

It’s the only thing that will keep fashion. You can teach all the technical stuff. I don’t think we thought we’d get as big a reaction as we got. That was our sort of world, it all made sense, and none of us had any money. We thought, “how do you still get people to see how your world is?” Now you read about Dior spending £1 million on flowers, it’s just in such bad taste, isn’t it? This idea of extravagance purely for extravagance. You could do so much more with £1 million.

“How much of the fashion audience do you want to please? And how much do you not want to please them?”

I’m sure one could make an impact in a different, clever way.

I suppose that spending £1 million on flowers is like someone saying, “I put £1 million of Swarovski crystals on a dress” — it becomes meaningless. Does that make the dress better in terms of its design or not?

What we were trying to do, was to push peoples’ buttons in terms of how they reacted to a fashion show, and also take fashion outside its comfort zone. I was always really aware that if “this” [makes imaginary limits with hands] was the perimeter of fashion shows — if you took people out “here” [beyond limits], they might not like it, but something “here” [inside limits] would be a lot more comfortable for them. So actually, you could really take them somewhere they didn’t want to go, somewhere uncomfortable that was challenging. That was something that made them — when they went away — start thinking about things.

What do you think about the shows Rick Owens has done lately? The one where people were hanging in the sky, playing rock music, hanging their dicks out, is kind of like forcing you to enjoy a theatre you might not have chosen to go and see voluntarily.

I like anyone who’s exploring the preconceptions of what a fashion show is. Not many people want to push you somewhere to make you think “wait a minute, am I comfortable with this?” I think the ultimate is still that McQueen show where there was a glass mirror!

The one with the mental asylum?

The fact that they had to sit there, looking…

For two hours, right?

It made them so self conscious.

That was all on purpose?

Mhmm. I think that’s an interesting thing, how much of the fashion audience do you want to please? And how much do you not want to please them? With anything that’s a live experience — theatre or whatever — sometimes, it’s not necessarily about pleasing the audience.

“I remember Louise saying that thing about wishing she wasn’t in fashion, because everyone just wants to get involved and have an opinion.”

In a documentary, you mentioned the importance of shock value, and how people otherwise won’t notice a designer. How do you think we can still add shock value?

What I always think about, is that iconoclastic thing of wanting to go against whatever the norms are. Everything is boring. I was having this discussion earlier, with a student; the handbag on the runway only came back, because Antonio Berardi showed handbags on the runway in ’98. At the time, everyone laughed at him and said, “this is so old fashioned, why are you showing handbags?” Literally ripped the piss out of him and yet, now, it’s absolutely the norm. Every design has a handbag. You don’t even notice or think what that means. There was a time where it was ridiculous.

Why did you stop your own label?

The misery. Why did I stop? At the time, there was no financial backing or help. It was when Valentino had lost the rights to his name. I had this realisation: it didn’t matter how big you became, it wasn’t going to get any better. Problems were still going to be problems, but instead, on a much bigger scale. I just thought, “oh, I really could do without that”. Weirdly, I haven’t found the answer yet. I looked up what happened with music, and how musicians managed to free themselves from the production and take a product to the market. I thought, “oh gosh, if there was a fashion way of doing that”, where you didn’t need to source production, you didn’t need to use shops, and you could then sell on a scale you were happy with.

Andrew walks through his office, and fills two cups with water, then thinks for a moment.

I remember Louise saying that thing about wishing she wasn’t in fashion, because everyone just wants to get involved and have an opinion.

Fashion is fashionable.

And it’s not helping us. It’s really a hard, boring job. It’s very technical, it’s very skilled. You think of all the madness of it. I can’t think of any industry where you’re bringing a number of products to the market every six months, or every three months. It’s just madness. Downstairs, we’re working on a pre-collection. So they have 6 weeks to do an outfit of three different garments. They’re having to research, design, develop, prototype; all of that, and make the final prototype. In six weeks? That’s fast, but not as fast as industry.

“You’ve got to have that self belief that you’re doing something better than whoever.”

Where do you think that change in the fashion industry will come from?

I think it will come from where it always comes from, which is young people. It’s the next designers who are saying “[blows raspberry] this is rubbish”. We’re rejecting all of this, just like they rejected couture. You just reject it all. That was a thing at St Martins: rejecting the things from the year before, the successful ones. Everyone in our year was going, “they’re rubbish!” You’ve got to have that self belief that you’re doing something better than whoever. Eventually, people will think that “oh actually, there is another way.” This idea that you do a foundation, a degree, an MA, then you get a job, go to a company and suddenly you’re at LVMH and you’re head of Loewe or YSL… I think people want to be their own designers again.

Having been the course director here for the past 11 years, what do you think has been your greatest experience?

The bit that really excites me is seeing them in the first week, when they don’t know what’s going to happen to them. In the first week of the final year, they all look dressed up, they look great; I say to them, “you’re not going to look as great as this in 6 months, you’re going to look dreadful. Let’s enjoy it today, while we can.”

It’s that last year when you see them really coming into their own as designers. By the end of those four years, they’ve decided who they are as designers. While the world might be all about Kenzo or Celine, if it’s menswear or denim they’re obsessed by: great! That’s the bit that excites me, because I know they’ll have a longevity in their career.

What do you think you’ve learnt most over the past 11 years? To be more objective?

Yes, but I guess I always have been. What’s really exciting, as a teacher, is engaging in forty different peoples’ worlds. It’s a real privilege that someone lets you into their creative process, and to actually see how they work and where they’re going, and suggest where they might go. By the time you’re with the final years, it isn’t about teaching, I always say, “it’s about learning.” You’re going through a process together, and by the end of it, you’ve both learnt something.

“Somehow I put on a show with no mobile phone, no internet… In those days, how did we put a show on, as young designers? How did I contact the model agencies, or hair and makeup, or even send the tickets out?”

There’s been recent changes in fashion education: Parsons’ Simon Collins just left, Louise Wilson passed away and Wendy Dagworthy has retired. You’re still here, after 11 years. Do you see yourself going through a change? Are you challenged, or do you want to take on something else?

I know Louise would have said this, and I constantly do: we have to turn everything off (as much as possible), in terms of the exterior of studying fashion — the fees, funding, etc. As tutors, and students alike: as much as it costs them, or as painful as it is, we still have to try and get an amazing collection out of them or their portfolio of work. As much as that can be draining, the teaching is so much fun, I can’t tell you. It’s a real pleasure.

Do you think that being taught by Louise has influenced you as a tutor?

I think her influence was far more on other tutors, than it was on designers. She taught me; she taught so many people. Her influence within everyone who was at St Martins is huge. I think I was really lucky, and at the time, I didn’t realise I was lucky. I look back at being taught by her and working with McQueen; if you say that now, you’d be like “amazing”, but at the time, it was just like, “yes, whatever.”

She was somebody who constantly wanted you to be the best you could be and wouldn’t accept anything less than that. Which was exciting: somebody was giving you a challenge.

“Louise made people think they had to do an MA.”

Do you think that the reason why so many people do or did an MA at St Martins, is because of the name that’s attached to it?

Louise made people think they had to do an MA, she was very good.

She was a good saleswoman, in a way!

When I went there, I left in ’97, no one was doing MA’s. It was really more about the BA. So it really was her, from ’94 onwards, making people suddenly go, “I want to do an MA.” It was really bizarre. Even when you interview students: “I want to do an MA”, “What’s an MA?”, “I’m not sure but I want to do an MA”. It’s odd, isn’t it?

“If you’ve got something to say, people will listen.”

People are now talking a lot about there not being enough support for young designers, but if you think back to the 90s, it doesn’t seem like there were any platforms to launch careers on at all.

I couldn’t get my head around this, last night: I had left the MA at St Martins, and then somehow I had put on a show at an old bus depot. If you asked me, I wouldn’t even know how I found it. Huge, I mean a huge bus depot. Somehow I put on a show with no mobile phone, no internet… In those days, how did we put a show on, as young designers? How did I contact the model agencies, or hair and makeup, or even send the tickets out? Yet somehow, it happened. It’s bonkers to think that Suzy Menkes was at that first show. Everyone you could think of went there, at a bus depot, just because I sent some invites. Crappy. Do you know what I mean? If you want to make it happen, you can make it happen. You don’t need those other things — they’re great as support, but you don’t need them, you can still do it. If you’ve got something to say, people will listen.

Do you think that if a young graduate would now write an invite and send it to somebody like Suzy Menkes, she would give it a shot?

I think any good journalist would. Because they think, “I don’t want to miss the next big thing.” They want to see the next designer who is pushing fashion forward. They come with the hope that this might be that next time. It very rarely is, but that’s what keeps everyone going. Despite what everyone might have thought about the shows, they’re still going to turn up next season. They’re not going to say, “actually, I’m not going to bother going next year”, because there’s that hope that someone’s going to do something really different, or brave.