Fashion writers today are likely to be tasked with an all-round sense of content creation and communication, ranging from social media, Q&As, video content, e-commerce copy and, if you’re lucky, good old fashioned long-form features on design, clothes and the fascinating moments at which fashion crosses over with culture and society at large. Today, brands and social media agencies are just as likely to be employers of fashion writers as newspapers or magazines. At publications, hardly any jobs are available for writers – most junior positions are paid 12-month internships – however, academic fashion journalism courses have never been more popular.

Not only have Central Saint Martins added ‘Fashion Journalism’ to its roster of fashion pathways, but independent companies, such as Condé Nast and Mastered, are charging eye-watering sums of money for access to their little black books, without any kind of scholarship or bursary schemes for students who can’t afford it – let alone the students that could actually benefit from such training. It all indicates that the demand to be a fashion journalist is heavily outstripping the supply of opportunities, and, what’s more, it shows just how much money there is to be made out of coaxing young people into faux educational institutions that promise them the knowledge and skills to land them a dream job at Vogue.

To put the record straight, we spoke to handful of heavyweight fashion editors to get to the bottom of what it really means to be a fashion journalist, and, more importantly, what being a fashion journalist actually is in this day and age. Forget those cash-swallowing fashion finishing schools; these are the people that can hire you and will train you to be the next generation of Suzys and Cathys and Tims. Pay close attention to what they have to say.

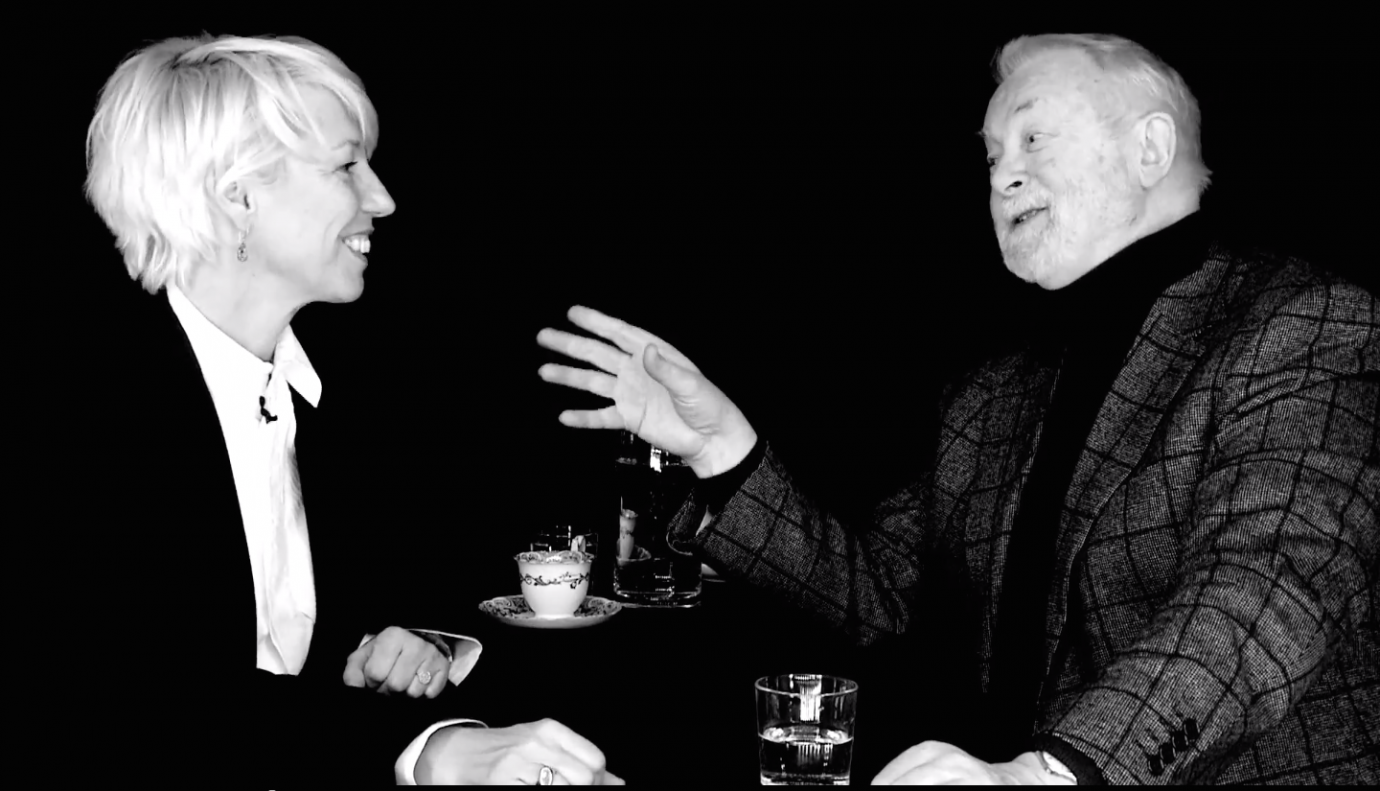

Sarah Mower OBE is a Contributing Editor and Chief Fashion Critic at American Vogue. Hers is one of the most distinctive voices in the industry, having worked for over 30 years at publications including British Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, The Daily Telegraph and Style.com, as well as authoring several books including Stylists: The Interpreters of Fashion. She is a decorated promoter of British fashion designers and holds the position of Ambassador for Emerging Talent at the British Fashion Council. As a fashion critic, she is the essence of what it means to write intelligently and knowledgeably about design, business and trends.

“THERE ARE VERY FEW PEOPLE WHO ACTUALLY CRITICISE ANYMORE OTHER THAN WHAT A STATE SHE LOOKS, HOW FAT SHE IS, A SORT OF TROLLING-TYPE COMMENTARY.” – SARAH MOWER

Fashion communicators are no longer the only communicators: brands, especially big ones, are now so involved with communicating their ideas directly to an audience. How has this changed fashion journalism?

The gatekeepers are not the same gatekeepers anymore. Now there are no gatekeepers – there are no gates! [Laughs] Long form journalism in fashion, it’s gone. Although perhaps, well there are far more fashion books now than there ever used to be: photography books and the rest of that stuff. I don’t know whether you can actually make any money in that area, but I used to be writing 3000 word articles. I still do occasionally, but it’s much more common to be writing a 200 word story for Vogue.com on a constant basis, so I don’t know. I just don’t know where all the thoughtfulness, where the fierce critique is coming from. Alex Fury is a shining example of that and he’s working in a combination of very old-fashioned, traditional ways, i.e. being the independent fashion critic – I don’t mean the newspaper Independent – I mean an independent-minded critic, which of course Suzy Menkes used to be and Cathy Horyn, and so on. His combination is that and his Instagram, so he’s straddling it. He’s fearless, his company doesn’t seem to care about what he says about who, whether he’s rude about companies or even a whole country, saying that Italian fashion is dead – that sort of thing. There are very few people who actually criticise anymore other than what a state she looks, how fat she is, a sort of trolling-type commentary.

I often wonder who the audience for serious fashion criticism is…

Well I‘ll tell you who’s reading it: it’s the company owners, and the buyers. That’s what it always used to be. And you know, if you have a strong enough voice, an authoritative voice, they’ll take notice of you.

In terms of writing about fashion design in the wider context of design, or fashion photography in the wider context of photography, it seems limited.

Well, you know, there can be an upside to this – fashion exhibitions: a well-curated fashion exhibition. It doesn’t have to be on the scale of Savage Beauty, but it can be the immersive experience where people can think and contemplate; have their minds blown by fashion and take it in with video and paintings. You know, everything to do with the culture that fashion is embedded in. And then of course there are catalogues and the rest of it. That is what I think, if I was your age, I would be doing now. And then I guess there are movies too, and videos. It’s just moving into a different place.