After finishing high-school (and his career in handball), Anders wanted to travel and experience the world. “I never really made it further than London,” he admits straightaway, as we meet in the incense-infused Shoreditch branch of Dishoom. He had a dream of becoming an actor and planned to be discovered on the street, like his then celebrity obsession, Jonathan Rhys Meyers. “I wasn’t discovered, but I think I was always quite creative, whether I was expressing myself through acting, painting or now, styling, it’s a similar approach. There was always something there, and that’s why I came.”

No matter what, there was a lot of catching up to do for the 19-year old Dane; after committing fiercely to handball for the most of his teenage life, Anders began to explore the nightlife of London. “I was always a very good boy, and well-behaved,” he explains. “Coming here, I came out as gay, and suddenly discovered all the nightclubs! There were lots of unravelling to do, and that sort of absorbed me for quite a few years. You come out of it after five years, and you think you’ve changed, but you actually end up as the person you were when you were 19,” he reflects.

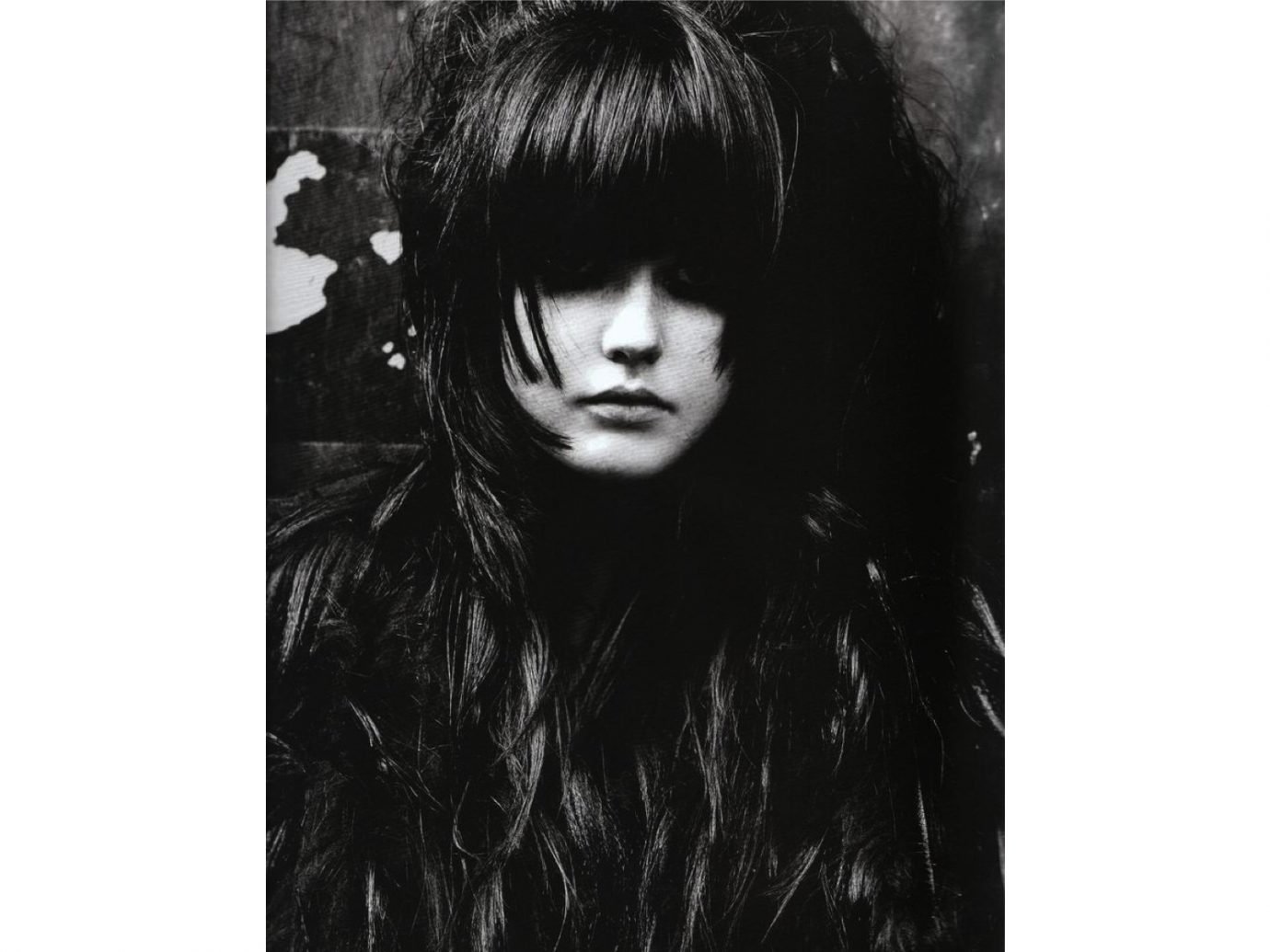

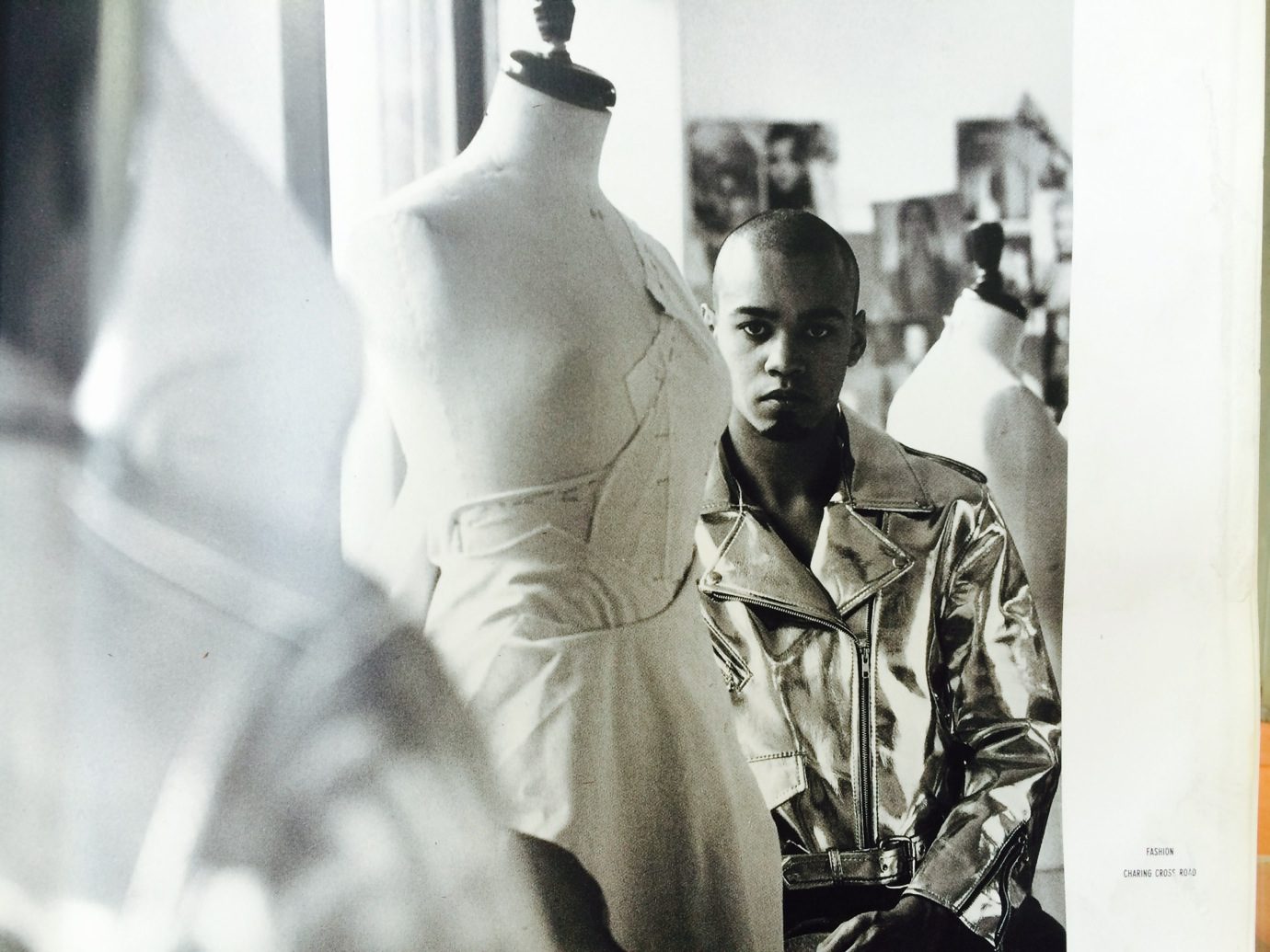

It was during his nightly outings that Anders started customising his own clothes, doing theme nights in Soho and South London. “Everyone would come up to me and be like, ‘are you a stylist?’ –and I was like, ‘what’s a stylist?’ I really didn’t know. I had no idea.” When his mother began pushing him towards beginning an education, a BA in Styling and Fashion Photography seemed like the natural choice. He never got to finish, though; by his second year he was assisting Katie Grand and simply “didn’t have time”.

“I never complained, I just got on with it!“

Anders’ entry point into the haute monde of the London fashion world was Camilla Stærk, a fellow Danish designer, whose NYC show he assisted at because his flatmate did her knitwear. “I was just hanging around,” he tells me. “I remember one season, I was doing all the hemlines and trousers and I had no idea how to sew!” It was here that he met the American stylist Sally White (now Sally Lyndley). “After the show, I walked up to her and said, ‘if you ever need an assistant, I think this is what I really want to do.’ Three months later, she got a job as a fashion editor at POP, called me and asked if I wanted to be her assistant.”

At this point, Sølvsten was studying, assisting at POP and working fulltime in a restaurant at night. Never supported by his parents (except for his phone bills), he learned the value of money first-handedly while developing the fierce work ethos that characterises the industry. “I’d finish at POP at 6 o’clock and I’d run to the restaurant and stay until 2 o’clock in the morning,” he reminisces. “I had to do that five days a week.” How did he cope with it, I ask him, without having a nervous breakdown? “I think when you really want something, it doesn’t matter,” he says humbly. “I look at my assistant now, and he’s so driven. He sleeps in my studio if he needs to. When you see that sort of drive in someone… I think that’s what they saw in me at POP. I never complained, I just got on with it! I don’t see the point in just doing something half-hearted, because you’ll disappoint yourself and people around you.”

When Sally left POP four months later, he was asked by Fashion Director Victoria Young to stay on. He did one shoot with her (clearly as a test of his capabilities), and began working with Katie Grand immediately after. “It was a bit of a shock,” he says hesitantly. “I had been used to working with demanding people, but I’ve never been asked what she asked from the people that worked with her. I mean, even prepping a shoot for her was just so intense!” He clearly recalls his first shoot where he, proudly, had sourced several Westwood archive corsets and pieces. “She just threw it and said ‘this is not enough! We need more! I can’t work from this!’” he remembers. Sølvsten is certain that his training with Grand made him the skilful stylist he is today: “She really pushes you to your limit, but that’s when you get good. I understood straight away that you always have to dig more and work more because eventually, you’re going to find that person who will lend you three or four Westwood archive pieces that have never been seen before.”

Although fashion is an industry that values impeccability to an unusual extent, Sølvsten would not murder because of mistakes. “Everyone fucks up,” he argues; “but I think it’s about how you deal with it. If you try to cover up that you’ve messed up, that winds me up and I get pissed off. But if you’re honest, if you apologise and you have a plan on how you’re going to sort the situation, you can’t really say anything.” As Sølvsten was himself learning the craft rather autodidactically as an assistant, it was also, to a large extent, about attitude. “I was really good at poker face; I never looked stressed, and I think a good assistant needs that. If you’re looking super stressed out, everyone is going to feel it. When I go on a shoot, I need my assistant to be super calm,” he explains.

“Everyone fucks up – but I think it’s about how you deal with it. If you try to cover up that you’ve messed up, I get pissed off. But if you’re honest, if you apologise, and you have a plan on how you’re going to sort the situation, you can’t really say anything.”

As Sølvsten quit his studies and joined Grand’s inner circle of collaborators, he naturally joined her as she left POP to start LOVE, a new and playful addition to the Condé Nast portfolio of fashion magazines. He was promoted to Fashion Editor to be part of building a whole publication from scratch — an experience he will always think back of with excitement. “Katie ran the business and magazine as she did when she was at POP. We had to get used to Condé Nast, but we all sort of knew what we had to do.” They purposely installed themselves in their own office separate from Vogue House in Soho and worked intensively from the beginning to build their brand. “Being part of anything new is amazing and extremely exciting, as well as extremely nerve-wracking. There was a lot of pressure going from POP to Condé Nast, but it was a success from the first issue. Katie has an incredible vision and she’s very talented, also commercially: it’s hard for independent publishing to make money, but LOVE made money from issue one,” he explains.

Thomsen actively tries to separate life and work, and appreciates not coming home every night to discuss fashion, despite living with his boyfriend, a fashion photographer. He still sticks closely to his friends from his party years, who never worked in fashion, and to his family, who “still don’t entirely understand what I do,” he laughs. Not that he entirely does either, as we discuss the functionalities of the styling trade. “It’s a strange industry. The whole concept of working so much for free, as well as investing your own money in shoots, is very odd. I do a lot of shoots where I invest thousands of pounds into them because the magazines never have budgets to cover it. I think that’s quite hard for someone outside the industry, and also for anyone new, to understand: you’ve got to be prepared to invest money into everything that you do. The big photographers will invest ten thousands of pounds when they shoot for an independent publication.” And as impoverished as one part of the industry is, the other is paradoxically abundant: “Once you start seeing the benefits, you start to get hired for campaigns where you get paid really well for your talent and vision,” he explains. For a stylist, it’s a never-ending balance between critically-acclaimed editorial and highly-paid commercial work, as one will only be possible when there is good cash flow, but will simultaneously attract the other.

In 2014, after working closely with Katie Grand for 10 years, Anders took the decision to go freelance, hungry as he were for new challenges. Compared to working within a large publication house, freelance life to Sølvsten is certainly more varied, but perhaps also a bit more solitary. At LOVE, he would be involved in every aspect of putting together a magazine, from attending creative meetings and doing marketing to overseeing budgets, casting and production. “So I literally knew everything about everything. I do miss that, but that also just means that your brain never sleeps. It’s never off,” he explains. With freelance, it’s rather different: “Your week is never the same,” he says as he maps out a hypothetical working week. “One week you can be in Milan working for a client, and then you’re doing consultancy back in London, and then you’re doing a shoot, and then you’re having a prep day.” Characteristic to freelancing is also specific anxiety, as jobs (and hence, money) never come in a steady flow like in a corporation. “The hardest part of adjusting freelance life was understanding when you have your peak and off-peak times. You obviously want to be busy all the time because you want to feel relevant, but it’s impossible, especially as a stylist,” he says. “You’re always questioning yourself, and there’s no one that can really tell you if you are. Luckily, I have an agent now: when it’s like ‘OMG, I haven’t done anything for two weeks,’ she tells me, ‘calm down, just enjoy it, because next month you’re booked every single day.’ In his days off, Sølvsten takes his holidays and does meticulous prepping for future shoots: he requires two weeks minimum to prep a shoot.

While not as stringent as his former boss, Thomsen prioritises calmness and order during his shoots. He gets very irritated when things are not done but always tries to keep a good tone on set. “I’m quite supportive, and I try to involve my assistant a lot,” he says. Since early on, he developed a technique where he verbalises his thought process as he is styling, like a stream-of-consciousness, which sometimes is understood as an invitation to his assistants to join the conversation. “At times, interns think that I’m asking them to answer, which is quite sweet,” he laughs. “But that’s really just how I build up the look.” Looking back in time, he also knows that it’s not always useful to be screaming at the assistant when things do not work out. “If two looks were booked for a shoot and they don’t turn up, I still remember from my assisting days that it’s not the assistant’s fault,” he explains; “It’s the PR that hasn’t sent them, or they’re stuck in customs. So I can shout as much as I want at my assistant, but I’m not going to get anything from it — except making him nervous, and won’t be able to do the rest of his job properly.”

Generally, he advises all aspiring stylists to assist and get the industry experience that is impossible to acquire in college. With today’s super-connected social media, everyone can claim the title of a stylist, and somehow disseminate their work virtually, but that does not necessarily equal a long-term career. “I think a lot of the aspiring stylists think they don’t need to spend five years of their lives working their way up, as they can just go and arrange a shoot and put it out there and get however many likes on social media,’ he argues, “but that doesn’t necessarily get you any work or money, in the long run.”

“Styling is a job and skill that you build up over the years; it’s work relationships,” he reflects in a conclusion as we finish our coffees. “The difference between what I thought I knew 10 years ago and what I know now is crazy, and I learned that from working with some of the big brands as an assistant. I wouldn’t have been able to go and work for these big brands on my own, had I not had that knowledge. It’s about interning, assisting, sending CV’s out. Financially it’s hard, but as I say, get night jobs, get jobs in bars! There’s no shame in that. There really isn’t. Find a way!”