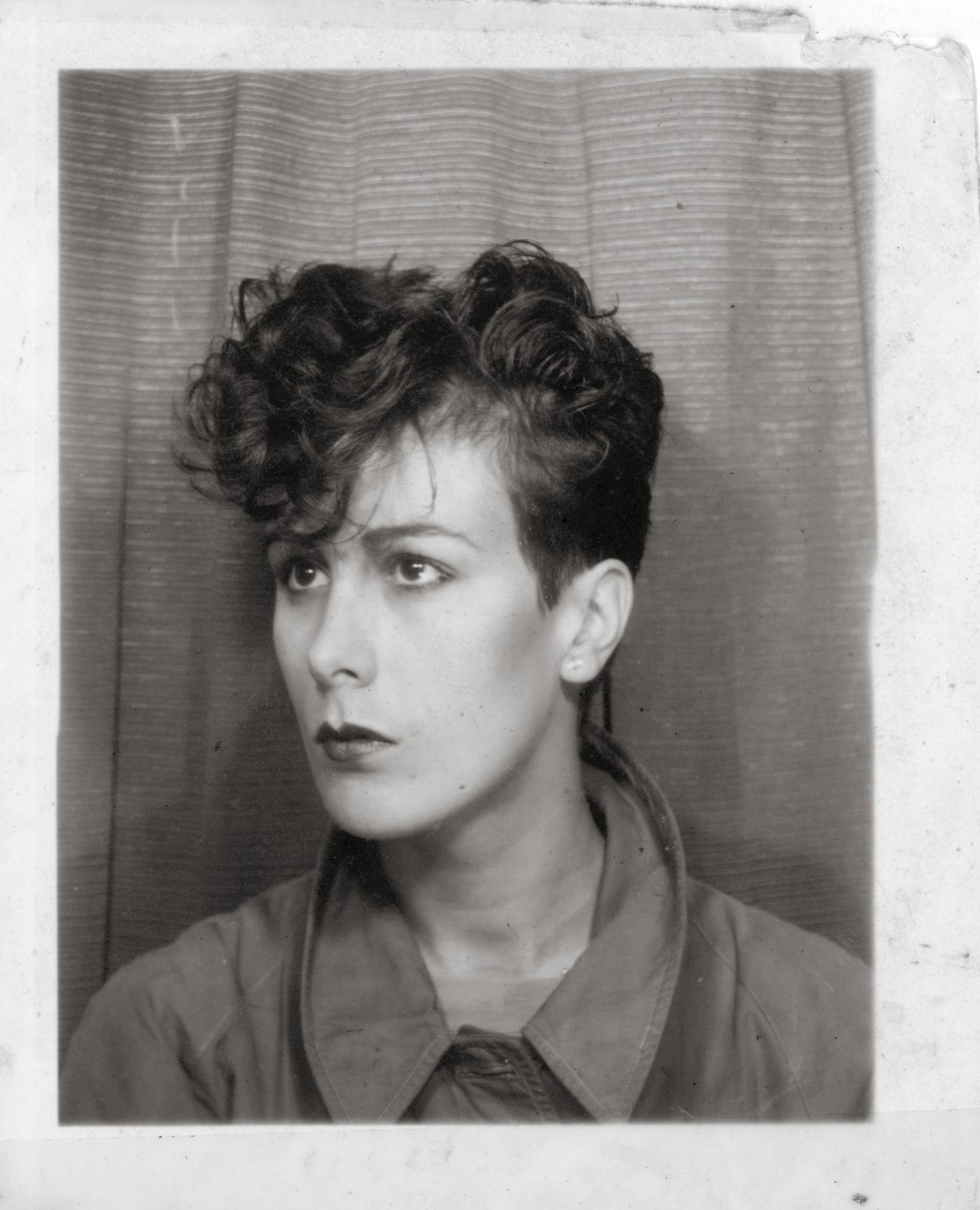

In 1982, after finishing a BA in graphics at Kingston and a postgraduate in advanced typography and photography at CSM, Franklin went to i-D for a job interview. After a few quick questions founder Terry Jones asked her to look after the office phone for the day, and take over where he’d left off with his Fiorucci art direction projects. i-D was still in its infancy, and the office basically consisted of Jones’ bedroom loft. He stayed away till 5pm and offered her a job when he got back. She stayed there for six years, and in that time i-D grew beyond all recognition.

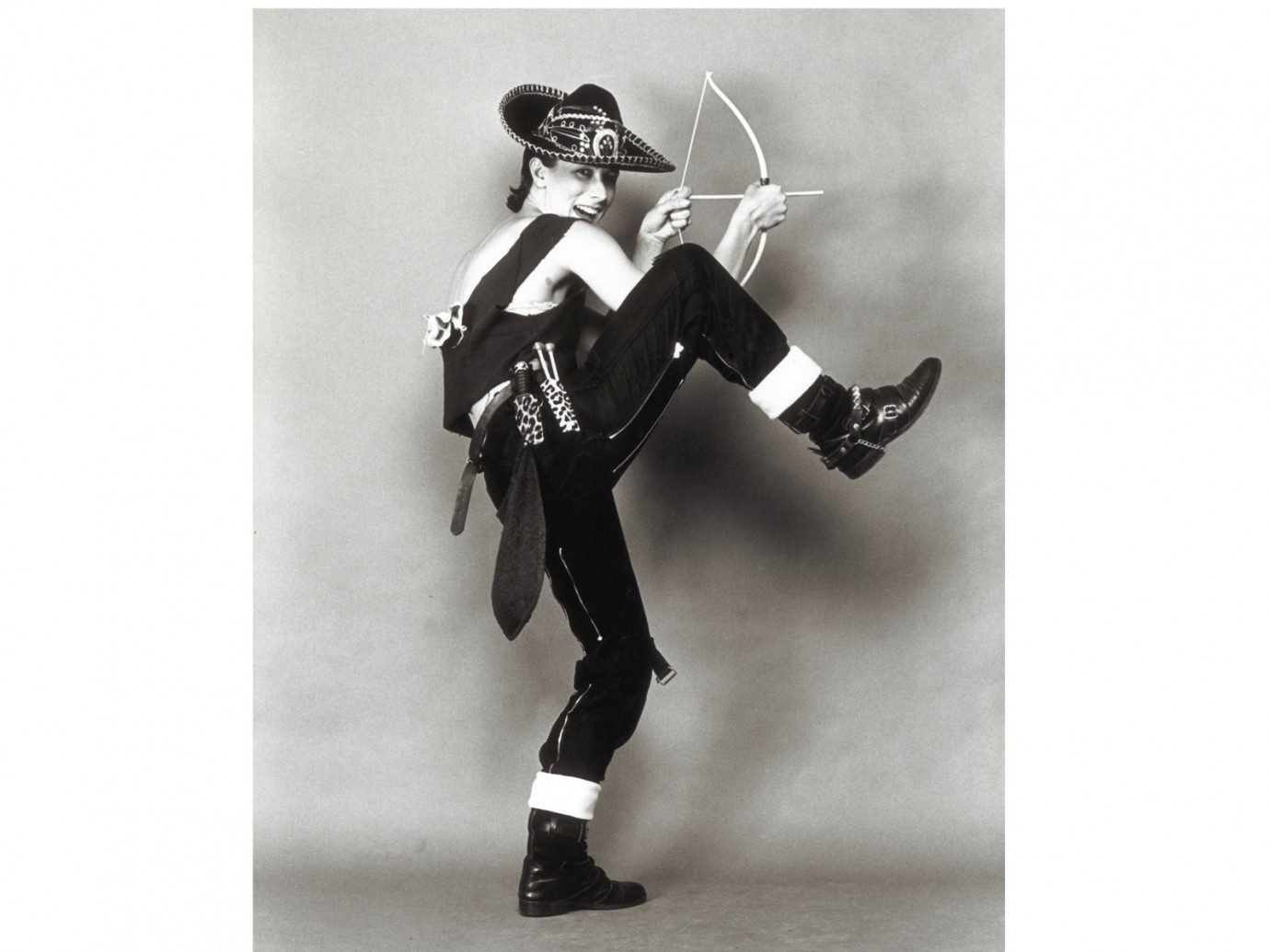

Part of her job was going to four or so clubs a night and documenting the young, penniless and full of promise – unheard of in a time when most publications only featured the rich and famous. From ’83 onwards there was increasing worldwide interest in London as a fashion centre, and i-D began to attract TV attention. Japanese camera crews would frequently barge through the door, and everyone in the office automatically pointed to the back, where Franklin was seated. From there she sort of seamlessly rolled into the world of TV.

“I BEGAN THINKING IN A MUCH MORE INCLUSIVE, EXPANSIVE WAY ONCE I ENCOUNTERED ORDINARY WOMEN WITH ORDINARY BODIES UP AND DOWN THE COUNTRY.”

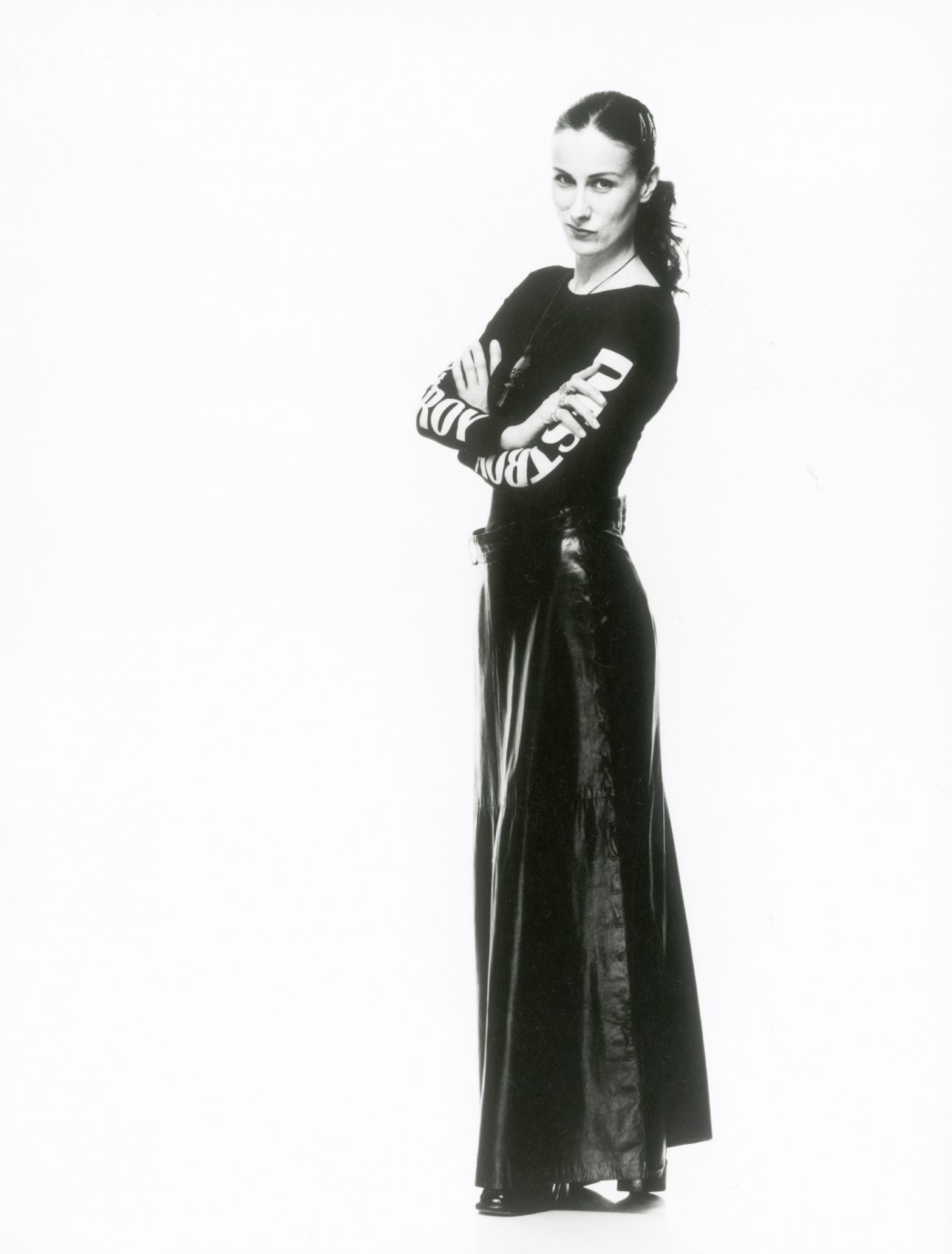

After some doubts – and initially kindly declining the offer because it was too mainstream – Franklin took on the job of presenter on The Clothes Show. From 1986 to 1998 she was educating the country about the fashion industry on prime time TV: explaining what a catwalk show was, why it happened six months in advance, and what happened in the six months after the show. They’d follow John Galliano, Vivienne Westwood and Jean Paul Gaultier in the run-up to their shows, and in the very same episode they’d be filming a housewife who had a tiny cottage business that she ran from a shed. “The joy of The Clothes Show was that it was always very democratic, and for me that was a big education. ’Cause having come from i-D, where everybody was very individual – and although not conforming to trend, they were very niche – I began thinking in a much more inclusive, expansive way once I encountered ordinary women with ordinary bodies up and down the country.”

When at one point she was thinking of stepping away from the TV programme – she was fed up with the BBC’s tried-and-tested formula and didn’t have the power to change the show where she felt fit – speaking to John Galliano changed her mind. “He told me ‘What’s really great about The Clothes Show is that I can now get in a cab and the driver will immediately recognise me and talk to me about fashion, and we will have a conversation that we never would’ve had before.’”

By this point Franklin was public property. With only four channels on TV, The Clothes Show had a 13-million audience every week. With it came a responsibility. People didn’t have access to fashion editors, and didn’t always know what they looked like. “But they knew what I looked like. I could be anywhere: I could’ve just had a tearful argument with my partner or I could be consoling my small child about something, and people would just step up to me and go ‘You know, I’m really sure my daughter’s got an eating disorder. What do I tell her when she says she wants to look like a model?’” She began to absorb the issues that were affecting her biggest audience, and the one that repeatedly cropped up was body image.

“YOU KNOW, NOBODY PAYS YOU A WHOLE LOAD OF MONEY FOR ACTIVISM.”