Agencies also seem to put limitations on publications – with regards to whom you should be working with, for example.

There’s a lot more control of talent at all levels. Breaking out of that makes it interesting. I think you can’t say it was better then and isn’t as good now. To make good images now you have to fight for that time, to reclaim it. Not play by the industry’s rules but hack the system and make your own rules within it. There are great magazines out there. I love Buffalo, Modern Matter, 032c, Re-Edition. There’s plenty of interesting people making platforms for great fashion photography and doing great edits, publishing great images.

I think in the past, it was also very concentrated. When you think about it, there weren’t so many magazines, so we were also quite lucky. We had the pick of everybody. Talent didn’t have as many places to go to. There were a few different publishers, but it’s nowhere near what it is today.

I am very positive about the fashion industry – but when talking to you, I try to pick something negative to provoke a response. But you’re so enthusiastic about everything.

Right now, young people are questioning things more than ever. Much more than my generation, and I think that’s absolutely brilliant. It’s about questioning and being an agent for change. I think that will produce interesting views, formats and types of media. I was really lucky because I met amazing people who helped guide me along my journey. Malcolm McLaren was one of the people who really influenced me. I remember interviewing him in 1995 and he said: “The culture doesn’t want what’s authentic. Mainstream culture wants what’s easily commodified, what’s easy to make money out of. It doesn’t want to be authentic.” He said that we are living in a karaoke culture. Society doesn’t want chaos, failure, the unpredictable and the messy. That’s not what people want to buy into.

In 1995, he said to me that humans will become more like machines. Less failure, less authentic, more about perfection. He said: “The machines are taking over, Jefferson.” And that was in 1995. He was so ahead of his game and so visionary. I love that. I didn’t understand everything he was talking about, but I felt the emotion he was talking about, and he was really always one step ahead and always challenging the status quo. He said to me: “It’s better to be a flamboyant failure than a benign success.” I thought that was fantastic. Who wants to be a boring successful person? I thought that even though financially he wasn’t successful in society’s terms, I would always see him as somebody who successfully found a position for himself to be that agent provocateur, that agent of change. A lot of the designers, artists, filmmakers, musicians I am interested in now, they owe a huge debt to him particularly. I think he is a massively underrated force for change in culture. I was really lucky to meet him and certain people like him. They gave me confidence and made me aware that it is possible to keep going. Not caring about what other people think of you, the press, whether you’re getting validation or not. It’s important how we feel about what we’re doing. If it feels right, it’s right. But we also overthink things. It doesn’t matter if it doesn’t make money.

WHO WANTS TO BE A BORING SUCCESSFUL PERSON?

Sometimes change can be really obvious. Like doing a bi-annual format and changing frequencies. There are other things which are less obvious, where you don’t even know change is happening. But it happens by a process of putting one foot in front of the other. Not giving up and sticking to your beliefs, with a group of other people who are inspired by similar beliefs. Your group, in a way, starts changing things in the industry, and there is no manifesto for that, or a clear construct, but it happens. Those silent forces of change are more interesting to me than the obvious ones, where you set goals and ambitions. We have always been very much about positive storytelling, and that includes a network of contributors that have been loyal to us and we to them. What goes on behind the scenes, that ability to support each other as a network and provide a platform through a system of production. Regular contact allows people to be a part of the extended Dazed family. That’s really important to me, always.

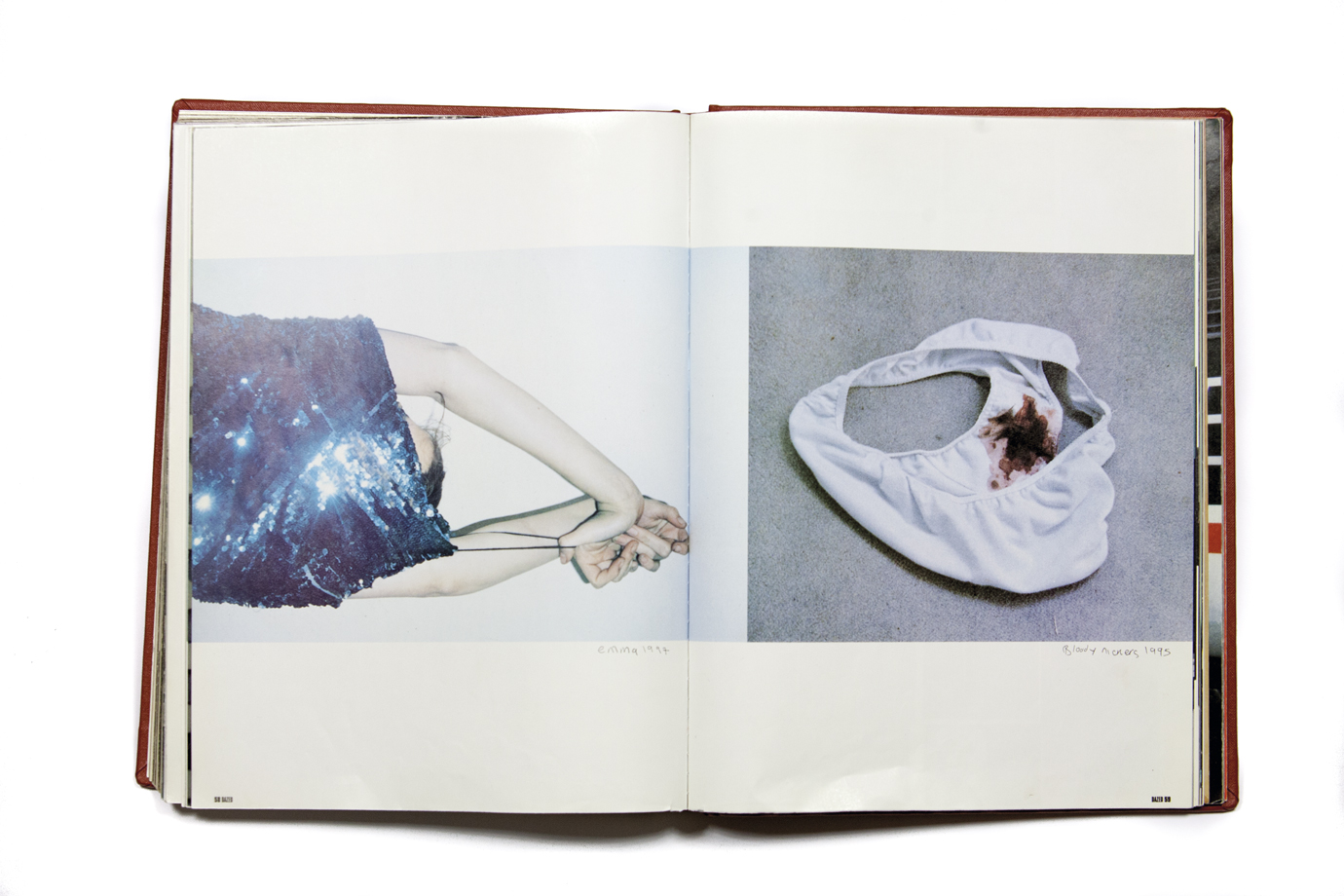

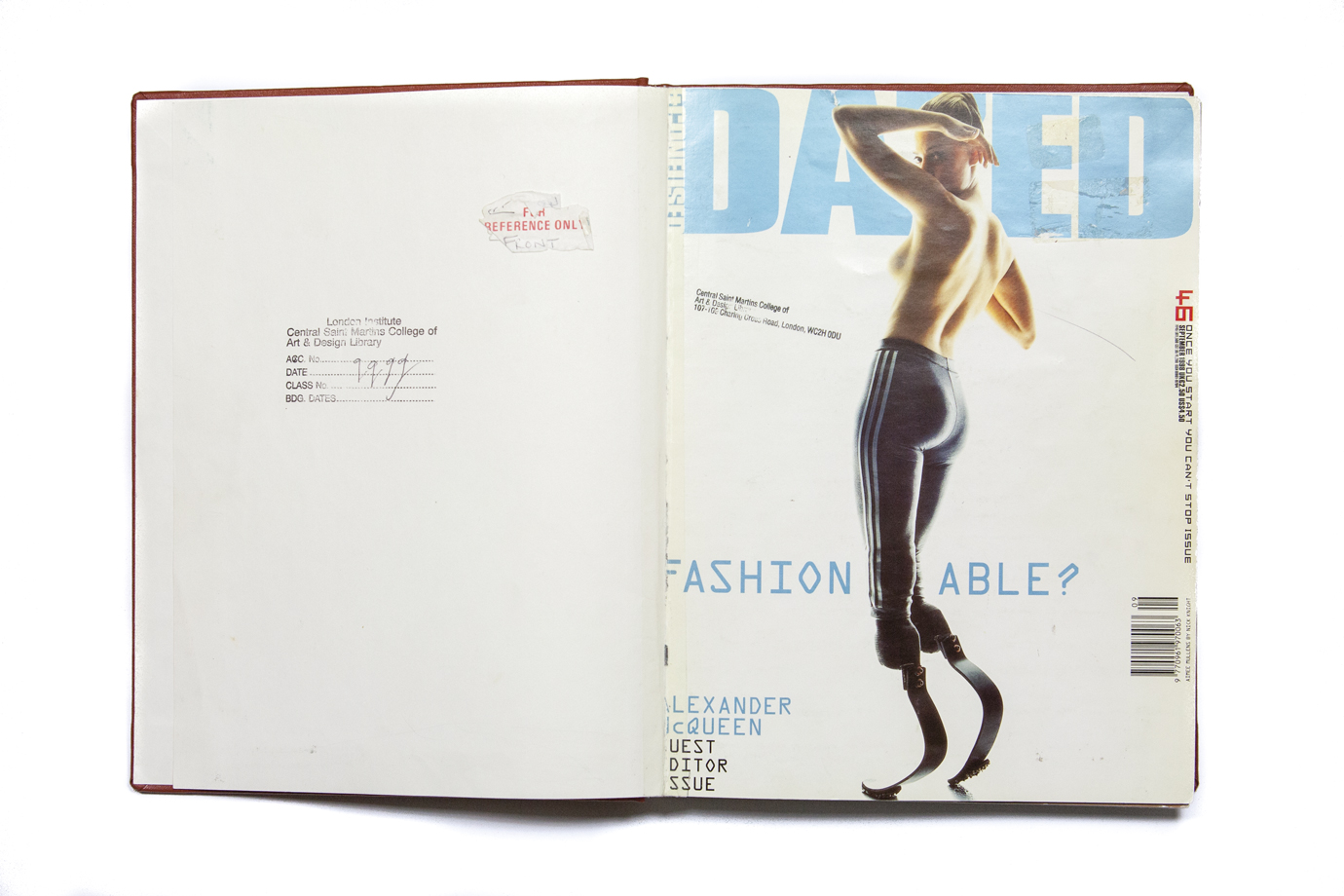

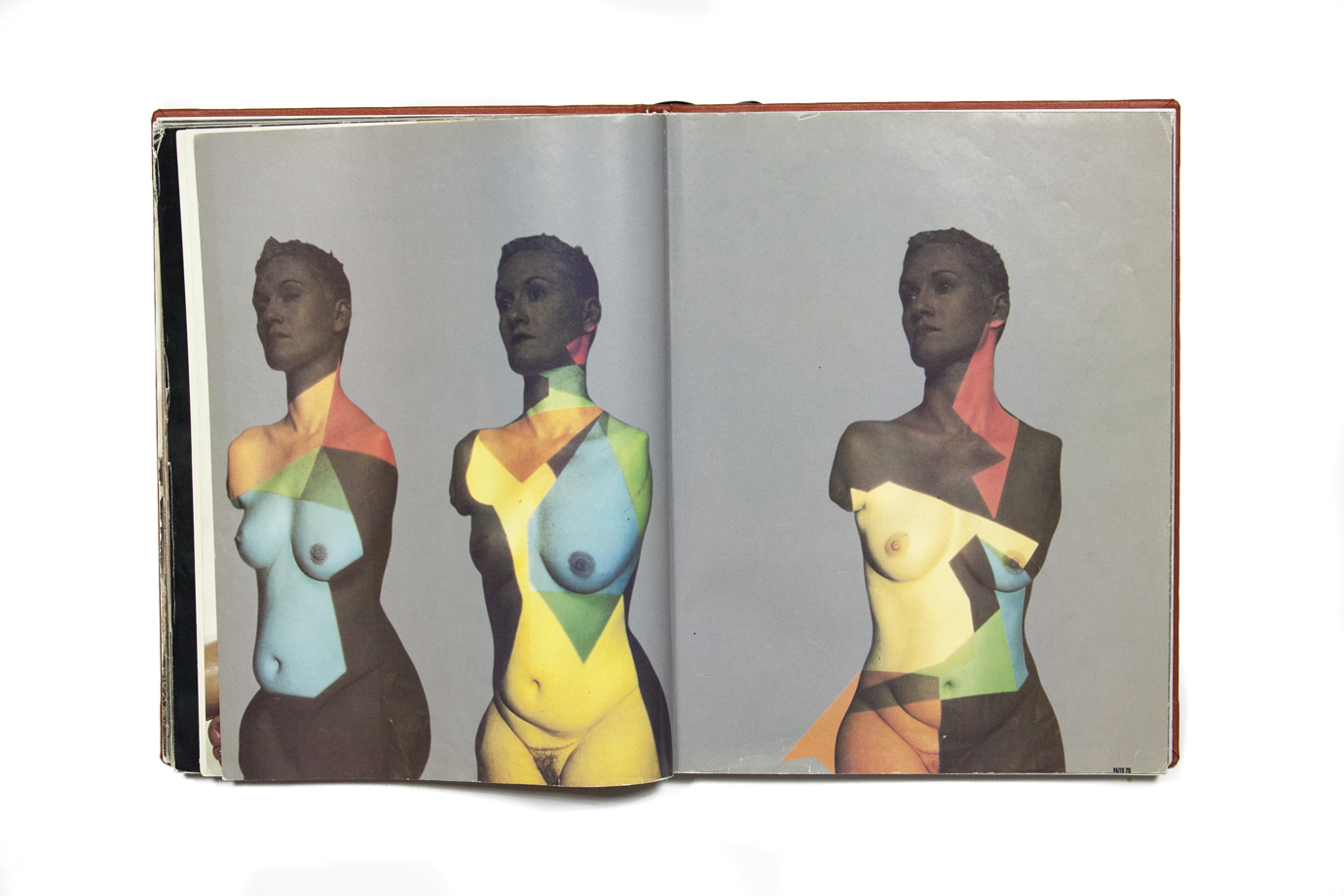

Things come out in different ways, like exhibitions or events, or us supporting other people’s projects. Many magazines come from people who started at Dazed and produced their own publications, and that’s wonderful as well. I think I’ve also always been conscious as a publisher and editor that you have a responsibility. You are influencing the mind of the reader. That’s a power, and you can use it and manipulate that power for good or for bad. By supporting a lot of new talent, it sends that message out that if you believe in yourself, you too can achieve your dream and find your voice. We’ve very consciously done that right from the beginning. But then it’s also about promoting diversity in body image, racial identity, LGBT – having those conversations in photography, but also in interviews and other forms of dialogue. You know, subverting taboos, but with a message of what I would call ‘punk-positivism’. Punk in the sense that we are interested in an idea of unprofessionalism: you don’t have to be ‘somebody’ to do this. You don’t have to come from a place with authority. That point of view of punk, and the idea of creating with what’s around you. It doesn’t have to be expensive. It can be found material – but then applying that in a positive way, so there is a purpose to it beyond a look. In many respects, the kind of nihilism of something like a rock’n’roll, punk or hardcore aesthetic, is often about looking the part without having much to say. We wanted to avoid all those traps, stereotypes and clichés, and imbue what we do with a sense of positivism.

What are your main concerns for the future when you think about Dazed Media?

I want to show you a little bit how we develop the R&D projects that may or may never come out. This is something we just produced internally as a proposal. It’s called AnOther World, and is about how we create the world around us; either externally or internally, through architecture, design, psychology. It’s about places and spaces, travel, art, fashion. It’s really an exploration. We wanted to do it as an annual. I think the idea is that the annual is the new bi-annual. Experience the history of now. The idea is just to do one fucking brilliant issue a year and make it mind-blowing. The coffee table is the new newsstand. If I see a magazine at a newsstand, it probably means nobody is reading it. If I see a magazine on the coffee table of somebody’s house and I like their taste, I’m immediately interested, because it means they like that magazine enough to display it. It means that they identify with that magazine enough to have it as part of their world. It’s not something you’re just reading for guilty pleasure on the beach, and then throwing it away. It’s something they’re really proud to keep, reference and conserve. That’s my audience with this new publication I’m developing. For me, the ultimate place for this to live is on the coffee table, not the newsstand. I’m doing a limited edition straight to consumer. A little bit of distribution through some boutiques and art bookstores, but as much direct as possible.

Did you ever consider selling Dazed the way i-D did with VICE?

No, never. Nobody has ever asked us. I’m quite isolated from those conversations. I’m less interested in the business side – I’m much more interested in the creative side. But obviously, I’ve had to learn over the years how to protect the creative side by understanding the business that I’m in, and understanding how to make sure that I can be sustainable and grow as a publishing company. There is a key rule of discussions that I’ve had about selling bits of what we have, or creating different kinds of companies around what we have. The most important question that I always have is: can I have creative control?

If I have creative control, then I’m interested in having the conversation. But what happens is that as soon as you go in with that – a lot of the time when people want to buy into you, buy a part of you, want to do a project with you, usually they get scared and the conversation doesn’t go further. But in one or two instances it works, like with Nowness where we’ve got an amazing relationship with Modern Media, a Chinese publisher, and I find the business aspects of that really interesting. And to a degree, stimulating. But all of it is done with the full knowledge that I have creative control. Then I’m happy to have all of those conversations, but we don’t have many of them. That means I’m happy. It might mean we’re growing slower, or we might have to struggle more than other publishers, but it still means we’re completely independent. As a result, me having creative control means that all the editors on different projects have full creative control, because that’s part of the ethos.

It’s quite reassuring when you see companies like the Conde Nast e-commerce platform style.com crash. There was a time when you looked at the business world, and it seemed that if you didn’t have hundreds of millions to invest in a company, you wouldn’t succeed. But time showed those that start slowly, have an idea and build a solid platform actually get further.

Yeah, and you know, we have a lot more fun. We’re a lot happier, because there’s a lot less compromise. We can really do what the fuck we want. All of this [points at magazines around] is an example of that.