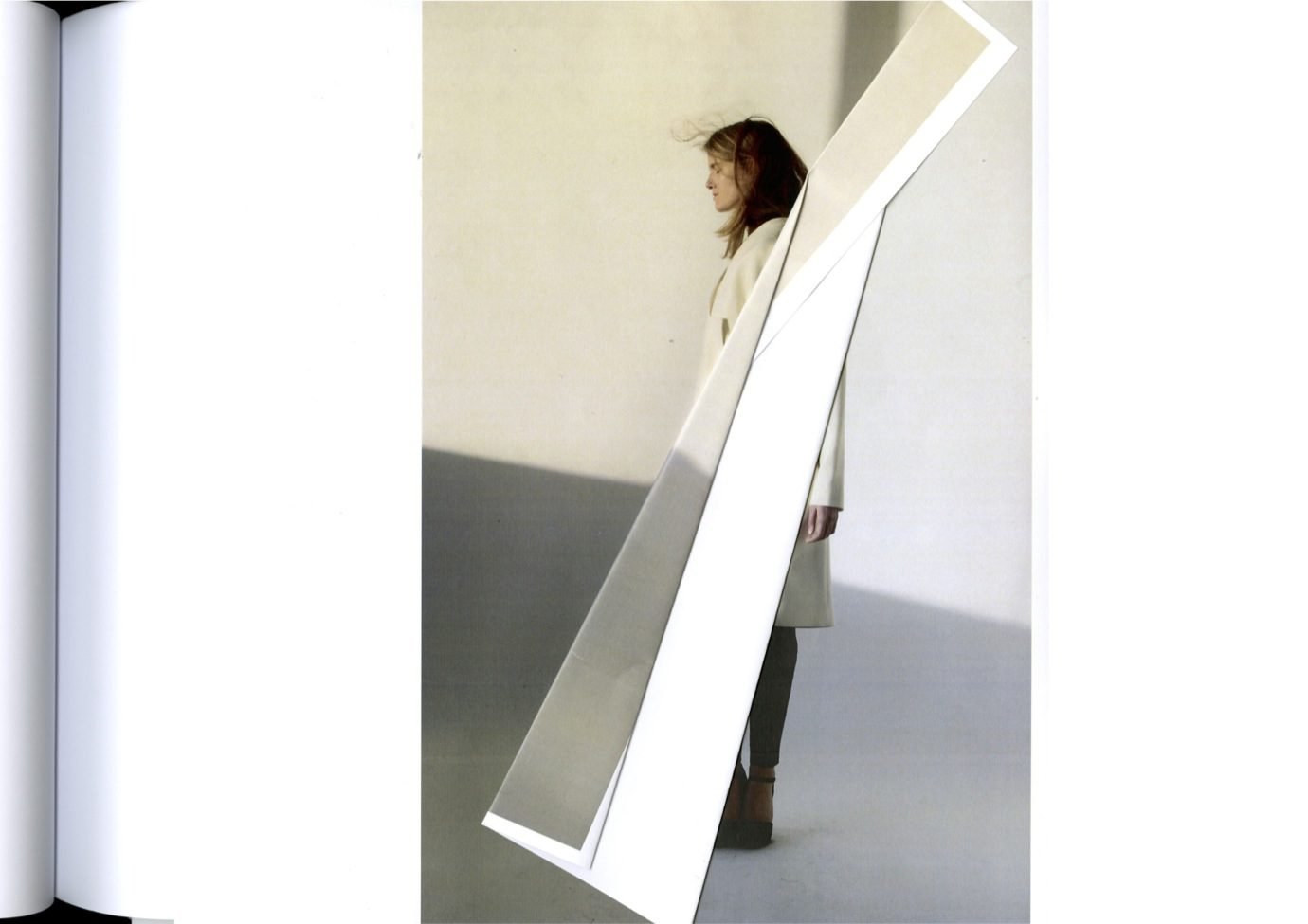

All the decorations had to be seen as something secondary, because the most important were the collections. In the showrooms, we provided a service to our own colleagues or partners to show the heart of the collections. It was very important to keep it balanced, and not to show ourselves (the design team) as too artistic, or too much into the architecture of the time, or too much into the design of the moment. We learned how not to boast or show off ourselves. The most important thing was the product. Everybody in the team learned a lot. When I started hiring people (I had a set decorator, architect and so on), it takes you some time to get into the mood. We found very quickly, with this attitude, not to do something too modern, or too defined by a certain period in the past, but to put those things together and to find a certain harmony with the furniture.

Another friend of mine said about the first shop in London: “I was walking around and there was something weird, I immediately felt like I was in a familiar place, and then I realised it felt like my childhood.” This boy was born in France. That was really a nice compliment. That he had that weird feeling, something he couldn’t put into words, and that I gave him this feeling using a couple of doors. In other projects as well, an installation with the Cité de l’Architecture in Trocadero and ELLE decorations for example. It was very graphic, a lot of grey and black, and silver; it was quite strict, yet somebody said that the space was feminine, and I was very happy with that comment because the company was known as women’s fashion. You see what I mean? When we had to prepare spaces for the women’s collection, the space had to be in a certain way feminine as well. That a woman could feel comfortable in a space designed by men. We had to think about energy. This was very subtle – some visitors even asked for their money back because there was nothing to see.

“MARGIELA ALWAYS WANTED VISITORS TO SAY – “OH MY GOD! THESE PEOPLE ARE CRAZY, LOOK WHAT THEY PUT IN THEIR SPACE.” HE WANTED AN EFFORT TO THINK ABOUT SOMETHING, NOT NECESSARILY SPECTACULAR, BUT IRONIC.”

That energy doesn’t just come from the decoration, but also from the location. Do you agree?

That was definitely a strategy in the past, to choose shops in more unexpected locations, which also was the solution to a certain economic problem. I think this has changed today, but again, even when the locations were in main streets, or close to main streets, the quality was… how to remain ourselves without falling into something more typical?

I think it relates back to this idea of negotiation. Everybody has a strong abstract idea about what Margiela means. When you translated his ideas to the interior, was it guided by Margiela? Or was it about you looking at his work and interpreting that?

There are two things. My team and I found ourselves exploring a couple of things that we saw in the collections, but one thing is a garment, and the other is a space. To consolidate this, I came to the idea to have a strict matrix, at least until 2008, or a few years until after Mr Margiela left the company. We had the advantage to work with him directly – taking pictures of inspiration together, looking at model scales to have an idea of the space – so the translation came from him directly. When I showed him something to do in a space, he was the art director; he guided us. He would sometimes say: “This idea is very beautiful, but it’s not us.” It was very interesting to work with the intuition and the energy, something that had to match with the company. That’s an exercise you learn over time, and later you feel free to propose new things.

Unfortunately there were always technical limitations, and we often had to work with an official architect for legal reasons – because we’re a fashion company, we couldn’t always do changes to a building. But it was interesting to match the profile of an external architect, who is used to doing things in a certain way, with our crazy ideas. The development of our projects was about negotiation: legal matters, city halls, authorities, and so on. It was very interesting because you learn what is possible in every country, and it gives you limits, which is very good.

Going back to your questions, I didn’t see the collections to get inspired, because the collections are unfortunately only one season and a space has to last more years than a single collection. With Mr Margiela, we were never immediately concerned for one or several collections.

It is true that the clothes always come first. When you enter a shop the interior isn’t in your face, but when you look further, you definitely notice it. Like the trompe l’oeil, for example.

[Laughs] That is true! The idea of the trompe l’oeils existed already, but was never captured in the right way. We first started using it very simply to cover an ugly door in the company. I liked the idea of a certain punk aesthetic and street art. The original one was done on photocopy paper, not real wallpaper, so it had wrinkles when you applied the glue, like a poster in the street. It had to be… not very nice, you see what I mean? It had to be like a spontaneous gesture. Then we started doing that in a more panoramic way, it was something that came – I cannot find the right synonym for spontaneous but I think it’s the right word – it had to be effortless. But it’s nice that you mention the trompe l’oeil, which shop did you see it in?

“WE HAD TO MAKE SURE NOT TO BECOME A SLAVE OF THE PAST.”

I’m from Brussels, so that’s the shop I know well.

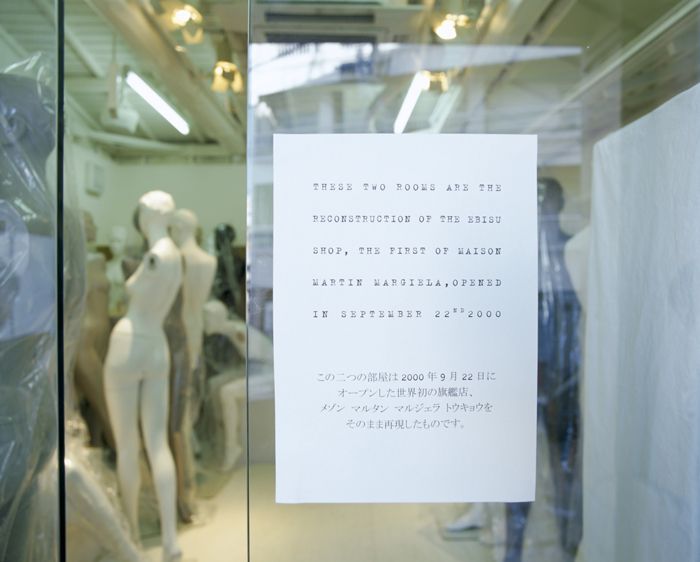

Ah, that shop is very small. That was a peculiar project because it was one of the first shops after Tokyo, and it was a partnership with the store owner, who put a lot of energy into the interior as well. It was also good to appreciate the perception of the brand from outside, something that happened to me multiple times with other partners and other people who did the other lines. It was interesting, and sometimes it was difficult for me to balance the perception from outside with my own perception. The owner in Brussels, for example, had the collection for years before she opened the shop. But it was this kind of negotiation between the external perception and our own work. It was a very interesting exercise in adaptation – to the moment, to the change of taste, to new expectations towards the brand, and how we could develop projects in different cities in the world, sometimes purposefully not taking the cultural context into account. Mr Margiela once said to me: “The important thing is that a shop, the general atmosphere, must be seen as something French, because we are a French company.” That was a very interesting brief, but making a shop in Hong Kong, making one in Osaka, New York, London, was very interesting for me who’s not French (so I have my own perception of what should be French). For me it was something surrealistic: we were in Asia, in North Europe, in the States, so how do you get your own identity from that city? The client must feel transported away, so you must work on the perception of people, if you see what I mean. They have to be astonished.