Cinema is a deliberately built microcosm. Sound, colour, narrative: nothing is left to chance. Instead of treating a film as an aesthetic source, we could study its methods of world-building and apply them to constructing a collection.

From Raf Simons being deeply inspired by The Night Porter or Helmut Lang by Stalker, cinema is central to design history. Alexander McQueen understood this transfer of method intuitively: “Films always inspire me… I have used them as visual backdrops in my shows, as they instill such an incredible atmosphere of emotion”.

But McQueen wasn’t just collecting images from films. He was translating their systems. This intuitive approach mirrors what film theorists call the Kuleshov Effect: the idea that meaning comes not from a single image, but from the relationship between images. Change what comes before or after, and you change the meaning entirely. A look in a fashion show doesn’t stand alone; its meaning shifts depending on what precedes and follows it. Designers often think in single outfits, but the audience sees a sequence. Once you understand that, the gap becomes obvious. It’s the difference between a collection that feels deliberate and one that feels accidental.

Together with MUBI, we wanted to explore how designers can integrate these lessons. This mini-series, Film as Method, deconstructs specific films and suggests ways to use the cinematic toolkit in your own practice in three chapters. Because this series relies on close viewing, MUBI opened a one-month window for our readers to watch the films discussed. You’ll find it at mubi.com/1granary

The Mechanics of Looking

Before analysing specific films, it helps to understand how visual attention actually works. The eye moves through a frame predictably: first to areas of highest contrast, then to faces, then along lines and edges. Every element carries visual weight, determined by size, saturation, and position. Cinematographers exploit these mechanics to direct attention precisely; so can designers. But these are components. What matters is how they combine.

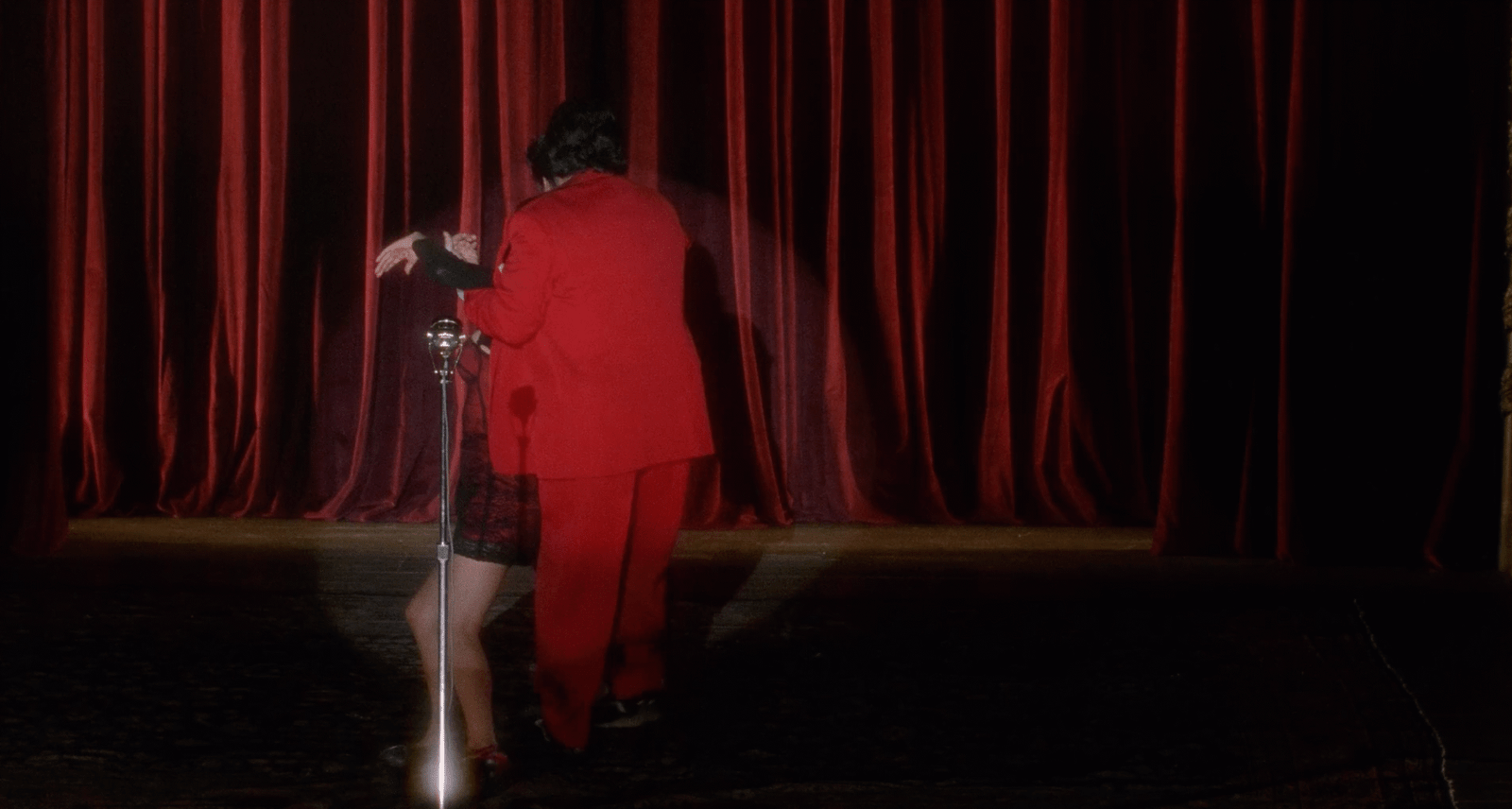

Filmmakers call this larger organisation mise-en-scène, a term that translates roughly as “placing on stage.” It refers to everything the camera captures: the positioning of bodies, the choice of colours, the quality of light, the depth of space, the presence or absence of objects. Mise-en-scène is not a single decision but the accumulation of decisions, the underlying structure that gives an image its meaning.

For designers, the concept is directly transferable. A collection is not a series of isolated garments; it is an environment built from silhouette, colour, casting, styling, and space. Each element influences how the others are read. A voluminous coat means something different when it follows a narrow tailored suit than when it follows another voluminous shape. A saturated red reads differently against a monochrome lineup than against a riot of colour. Mise-en-scène is the recognition that every choice exists in relation to every other choice, and that the frame, whether a cinema screen or a runway, is where those relationships become visible.

Understanding this changes how you watch, and how you can build in your own creative work. When we asked Lucy Moyse Ferreira, who teaches fashion and film at Central Saint Martins, what students miss when they first approach cinema, she pointed to exactly these fundamentals: “Students can initially overlook elements such as composition, lighting, and use of space. These details shape mood, guide attention, and convey subtext, yet only become fully apparent when viewing with deliberate intention.”

She suggests a framework: break a frame down systematically and ask, So what? Why was this choice made? What effect does it have? What would change if this element were removed?