Viola, often dubbed the godfather of video art, visualises the universal experiences of life: birth, death, and the many transformations in between. Showing things in their pure essence, most of his videos don’t involve much more than a person, maybe a few objects, and a background that doesn’t detract from the abstract message that’s being delivered wordlessly. They are the experiences that we cannot physically see made visible. Whether that is because the video is set at a speed so slow we could never physically perceive it or because the original experience is not a concrete or visual one. The sounds and the visuals are perfectly geared to each other, and the darkness of the space in which they’re played takes your attention away from anything else that could distract in the room.

I will never forget walking into Bill Viola’s retrospective at the Grand Palais in Paris last year. It was dark, and people of all ages were silently staring at his videos in awe. Many of them were sitting on the floor, entranced. The whole atmosphere was truly meditative. A bit bizarre even, seeing an audience completely transfixed by what’s in front of them.

There is a lot to be said about Viola, the depth of his influences (ranging from life experiences to medieval devotional painting to 19th century pre-film photography to Dutch Golden Age portraiture to Mark Rothko to Buddhist, Islamic and Christian forms of spiritualism) and where his work has sparked brilliance in others (compare the most striking scenes in Jonathan Glazer’s Under the Skin to some of Viola’s most iconic works and you will be pleasantly surprised by how glorious referencing can get).

But it’s hard to put into words how seeing Viola’s work for the first time in situ makes you feel, let alone the kind of lasting, transformative impact it has. It sticks with you, and sort of cracks you open in the way that drops of water can pierce a stone over time. On the wall leading up to his current exhibition at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park, the most extensive UK overview of his work for 10 years, are Viola’s own words: “I have come to realise that the most important place where my work exists is not in the museum gallery, or in the screening room, or on television, and not even on the video screen itself, but in the mind of the viewer who has seen it.”

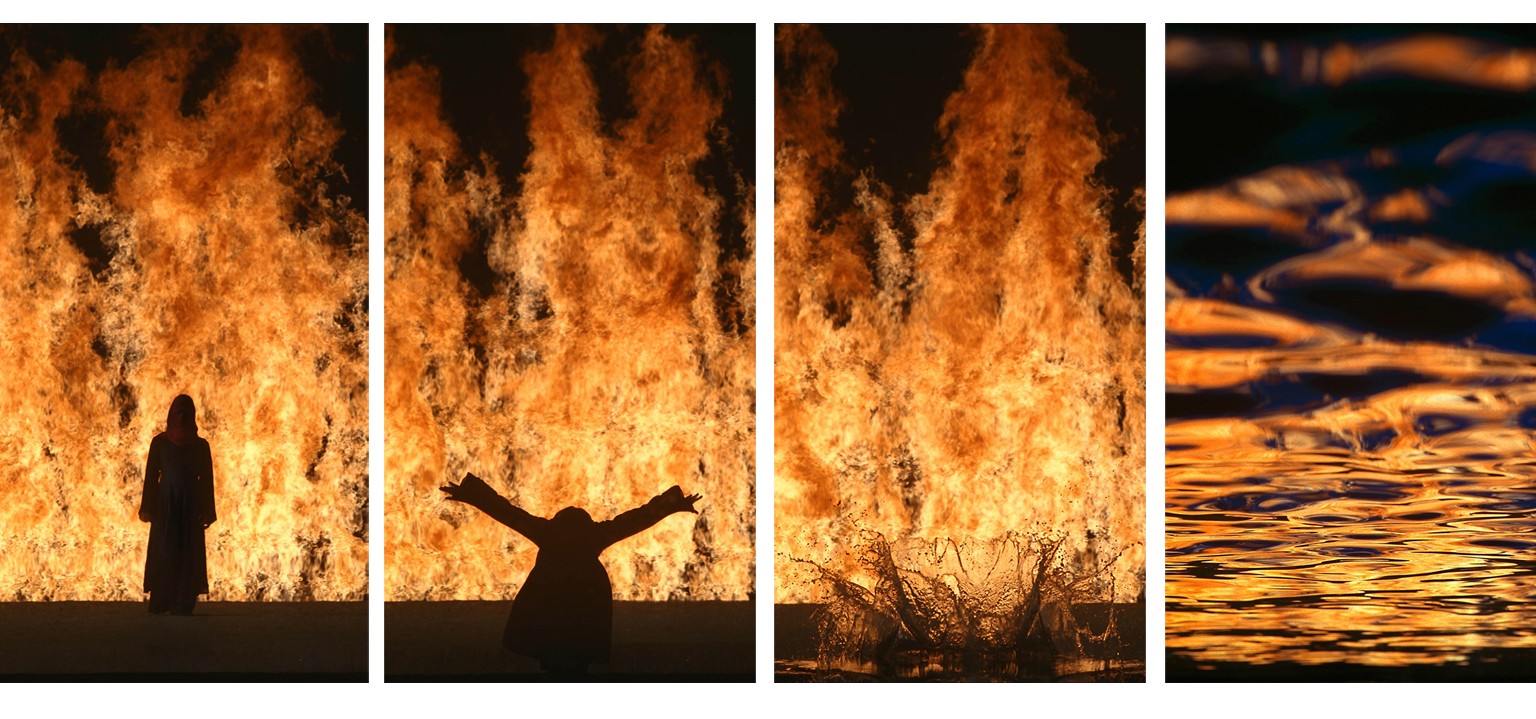

Water recurs in Viola’s work time and time again. He attributes this to the experience of falling into a lake and almost drowning at the age of six. It’s when he first discovered that a deep and beautiful part of life exists, quite literally, under the surface. In The Trial (2015), which has its debut at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park, a young woman and a young man are showered with a thick black liquid, which gradually turns into aggressive red and is washed away by pure, milky white which finally becomes crystal clear water. It represents, in Viola’s own words, “five stages of awakening through a series of violent transformations.” After all, water’s neutrons are always flowing, similarly to the neutrons that make up our bodies. In Tristan’s Ascension (2005), shown as a massive floor-to-ceiling projection in the Yorkshire Sculpture Park chapel, a man slowly rises upwards, as if pulled up by nothing short of the opposite of gravity, while a heavy flow of reverse rain moves up with him. It’s followed by Fire Woman (2005), in which a cloaked woman stands in front of a massive fire before falling into her reflection in a pool of water. Heavy sounds of water and fire respectively fill the space. The works are based on Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde, and the two videos of the lovers that are doomed but destined to transcend were originally created for and shown during an actual production of the opera. In Three Women (2008), a mother and her two daughters walk towards you. They look grey, grainy and ghostly, but after they help each other through a curtain of water, they emerge in unclouded, full-colour HD (but wet from their journey). It’s part of Viola’s Transfiguration series, visualising the abstract metamorphoses we all go through.

Moving Stillness (Mt. Rainier), shown at Blain|Southern for the first time since it was first exhibited in 1979, gives us a glimpse of Viola’s beginnings, and his own transformation as an artist. Environmental sound recordings are playing in a dark room. A white screen is suspended vertically above a physical pool of water. Three coloured beams of light in red, green and blue project onto the surface and form footage of Mount Rainier. The projection reflects from the water onto the screen and in turn onto the water on the other side of the screen. The exhibition invigilators disturb the quiet water at regular intervals, and as it starts rippling the image of the mountain gently becomes more and more abstract, after which the water naturally settles down and the original image reappears. The water, the screen, the light, the reflection and the disturbance of the image are great metaphors that bring to mind Plato’s Allegory of the Cave and Magritte’s Ceci n’est pas une pipe.

But it’s not just visuals set in dark spaces that make up Viola’s work. Sound (or lack of it) is as integral a part of Viola’s installations as what’s being shown. In the 70s he experimented extensively with audio and space and worked with pioneering composer David Tudor as well as Composers Inside Electronics, a group dedicated to the composition and live collaborative performance of electronic music. Electronic music was on the rise, and Viola even produced sound effects that were incorporated into samplers and synthesisers. Recorded in an empty swimming pool in Buffalo, New York, and exhibited for the first time ever, The Talking Drum (1979) and Hornpipes (1979-82) create an immersive environment of sound in the dimly lit and, bar a few benches and speakers, empty Vinyl Factory Space at Brewer Street Car Park. Sitting there and simply soaking up the echoes (both in the recording and in the physical space of the car park) is not entirely unlike the experience of listening to sounds bounce around in a church or cathedral. One part of the Brewer Street Car Park installation is even called Pulses (Duomo Bells). Viola spent 18 months in Florence during the mid-70s, where he worked for one of the first video art studios in Europe. He has spoken about his time spent in Italian cathedrals, looking at frescos and listening to resounding echoes, as the moment when he realised frescos in churches could be considered the first forms of installation art. It really is quite magical to recognise this in some of his earliest work.

At the private view for Moving Stillness we spot Mr Viola himself. It’s a surreal and risky experience seeing an icon in flesh and blood, but we decide to go up to Viola and ask him why it is that he is showing these early works now.

“Why now? Because it just had to be excavated out of… you know the American word “moth holes”? That’s what it was. And all of a sudden, you know, these pieces arrived. They went away for a long time…”

He continues after being pulled away for a quick picture by one of the gallery directors: “So anyway, just keep making work. Are you artists?”

We nod. “We saw your exhibition in Paris last year and it changed the way we look at life.”

“Okay. Then it’s your job after that to take that and then go over that, okay?”

He points over our heads, into the distance.

“And then that’ll be connecting with another person on the other side. That’s how it is. It really does work that way. It really does. You get older: all of a sudden you’re old, and then you’ve got to leave something behind for the next person. You have to do that. Okay?”

Bill Viola’s work is currently being exhibited at five different places in the UK:

- Martyrs at Auckland Castle in Bishop Auckland until 26 October

- The Talking Drum at Brewer Street Car Park until 7 November

- Moving Stillness at Blain|Southern until 21 November

- ARTIST ROOMS on Tour Bill Viola at The Wilson Art Gallery in Cheltenham until 7 February 2016

- Until 10 April 2016 Yorkshire Sculpture Park is hostingthe most extensive UK exhibition of Viola’s work for 10 years

- Martyrs is on permanent display at St Paul’s Cathedral