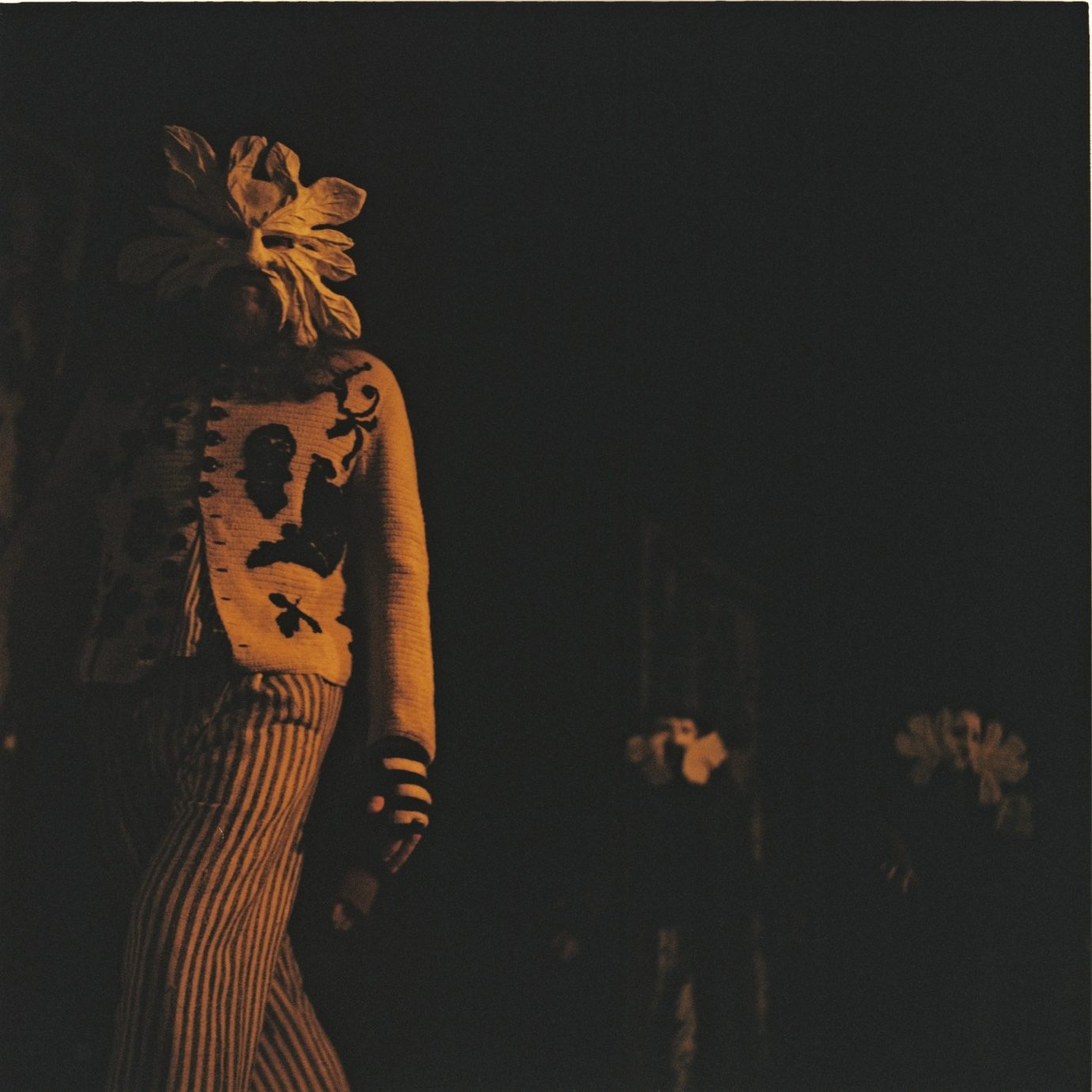

This performance, developed specifically for the Fashion in Motion series, was inspired by the Spring Equinox rituals of fertility and rebirth, drawing heavily on the pagan figure of the Green Man, “a warning of nature rather than a light-hearted symbolic thing,” explains Skelton, “but it was something that Christianity could take quite easily and incorporate, so it became popular to have on churches in the 15th and 16th century.” Banners adorned with depictions of the leafy figure stood in the gallery, and the hats and masks of the models reflected the Green Man within masonry.

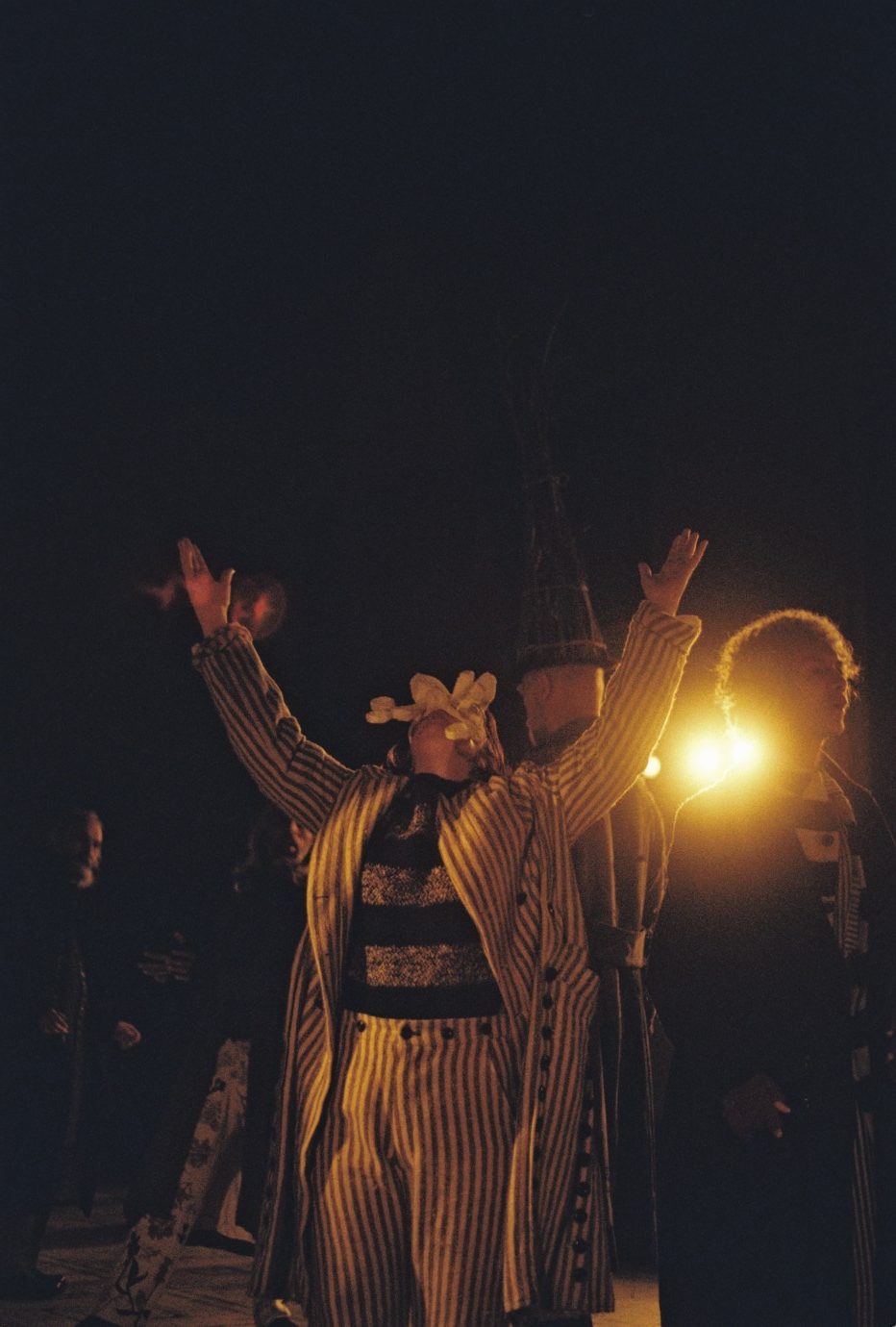

To begin there was some bafflement, some unsettled laughs, some awkward glances, but soon the spectators were mesmerised by a performance that turned them almost into participants. With the mystic singing voices occupying every corner of the gallery, it took on the reverence of a ritual that we were all taking part in, there were no mere observers.

The clothing, with knitted red and black immediately grabbing attention, felt quite a bit punk too, with homespun embroidery, fingerless gloves, the occasional rip, tear, or fray, along with its break from societal norms of how men are supposed to dress. The coats, as always with Skelton’s work, were the standout pieces, and almost obscenely beautiful. Though tonally amongst the quietest pieces of the collection, they demanded to be touched, to be worn, to be admired, expertly straddling the line between art and functional design.

The show finished, we exit from the performance gallery through the echoing deserted galleries of the museum at night, and come to the backstage area, which is brimming with excitement, warmth, and a sense of community between the models, assistants, and John’s immediate family. There is a particular buzzing atmosphere about his family: his mother, jovially asking one of the models to have a drink ready for her in the pub, visibly exuding pride; his brother Ryan, taking pictures of the performance.

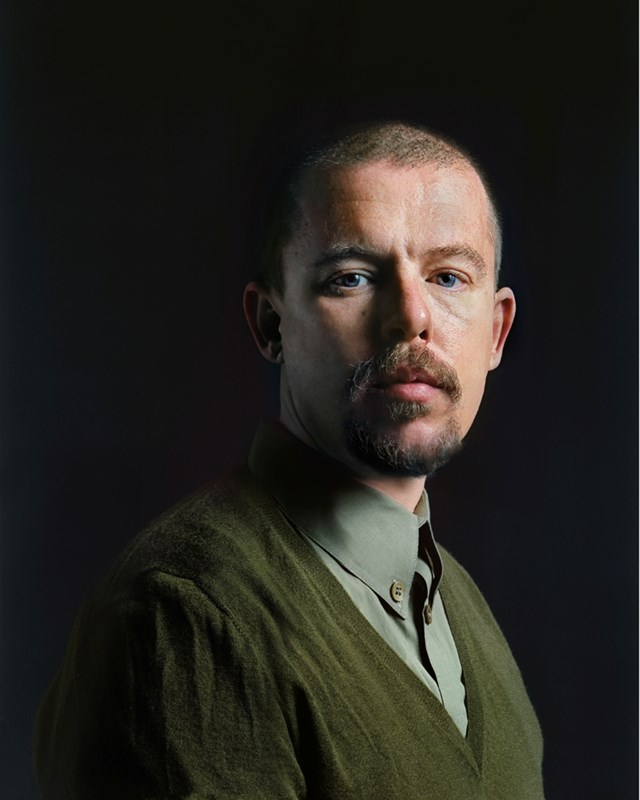

With the models changing and clothes being packed up, we finally find a room to speak in. Costume, in the end, is what it boils down to, or rather where it all sprang from. The slightly more nebulous period John had in mind for this collection was the heyday of British folk theatre. The aesthetic lands somewhere around the Victorian era but reaches as far back as the pre-Christian period, and takes inspiration from theatre costumes that were initially elaborate, but slowly reduced down to “a ribbon on a jacket” or similar, a progression Skelton dismisses as “really boring.”

Having previously touched on folk symbolism in the North, delving into pre-Christian British traditions has become a theme for Skelton, a rallying point for a more intrinsic culture of the United Kingdom, “No one knows anything about British folklore generally and it’s such a huge part of our culture,” he laments, “I think that they should.”

What he is attracted to, at the heart of it, is what he has always been attracted to: communities. A group of people bound together by shared activities, joys and spaces. People who learn to live together despite personal differences, in acknowledgment that the community, on the whole, has a power and importance than an individual does not.

“It was about a sense of community, working together and making their own costumes and doing it outside of their labour work, for fun essentially, which is something that is really missing in our current society,” Skelton admonishes, “I think we could definitely benefit from learning how to work together rather than this capitalist society insisting on the individual being better.”