After you graduated, when and why did you decide to launch your own brand?

I never thought that I was launching a brand. When I was 22, I worked at Louis Vuitton in Paris for a year, and I felt quite icky about that. Even though I loved the people that I worked with and some elements of the environment, I knew I didn’t want to be in a conglomerate. When I graduated, I had really good job offers but they were from houses in Paris, and I knew I didn’t want to do that again. So, I said I’d take a risk.

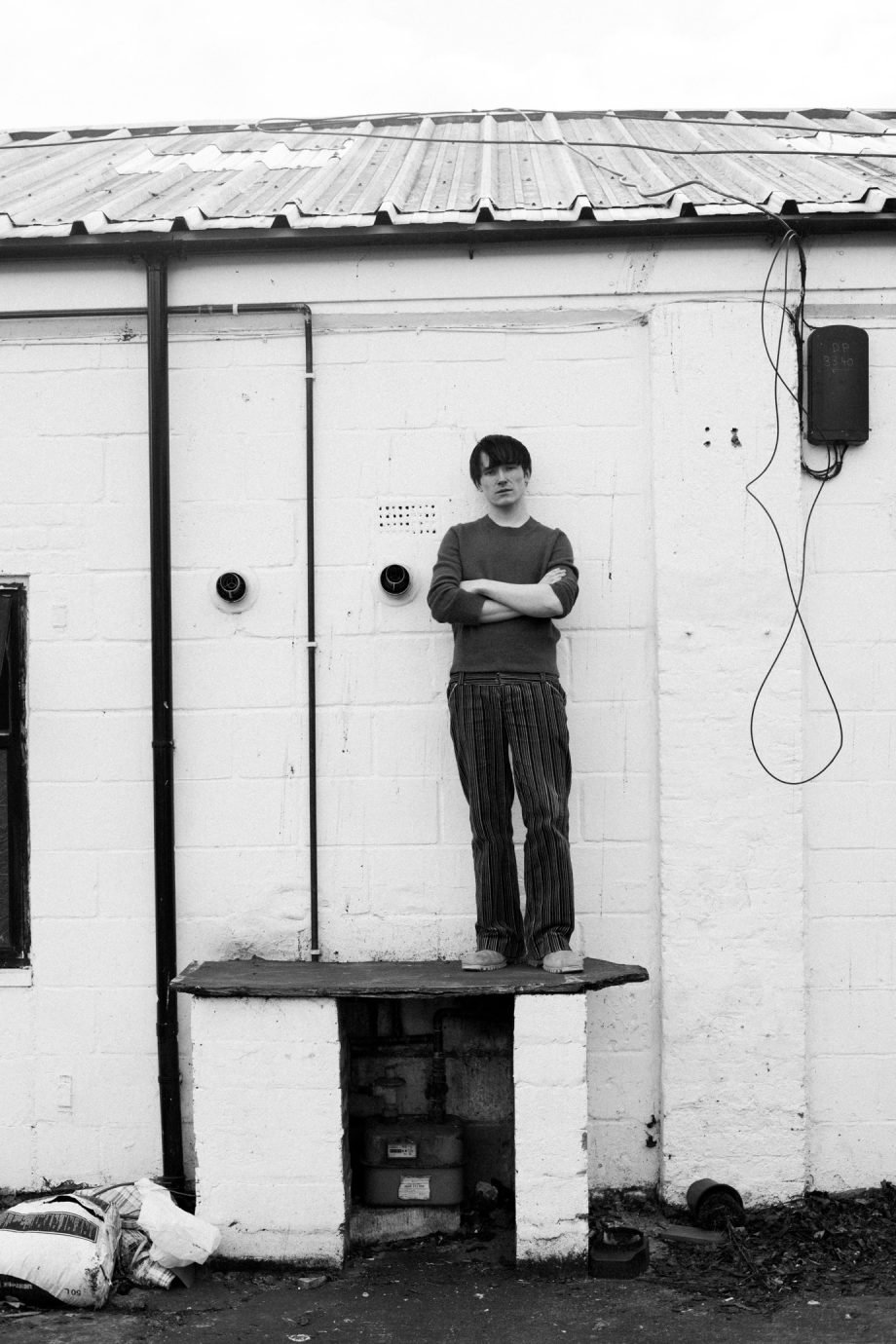

When we did the first show I had a prize – the Deutsche Bank’s Award for Fashion – and that gave me money to do a collection. I went back to Wexford and made it in my dad’s shed. It was always about having a practice, as opposed to launching a brand. I’ve always resisted having a thing that you do and doing it to death. A lot of people were doing that out of Saint Martins, but you can see that it only works for the people who are super rich – they’re the only ones that still have brands. I have to be very protective of what I have, and how I want to work within that.

“The reality of being at the top end of fashion or art is that there are very few people who are immigrants and who are working class.” – Richard Malone

As you’ve mentioned, you didn’t want to be employed by a conglomerate. What were the hardest and most exciting parts of taking that risk?

I think the hardest part was that I didn’t want to get a bad reputation. I’m very good at saying “no”. I’m quite intuitive, so if I feel like something isn’t right, I won’t do it. Sticking to that has been a really good lesson. The rewarding part was that a few amazing women started buying clothes from me at the very beginning. That’s the only reason I like it, the only thing I think is real about contemporary fashion – making clothes for someone with the intention of wearing them and thinking about the function of that. Otherwise, you’re just making images. When you have that spotlight on you, you can run with it. I thought I’d just run with it for a minute and see what happens.

“When I first graduated the only designers who were functioning were from the same area of London: Westbourne Grove or Notting Hill. Some of their mums were in the fashion industry or their aunts were famous people in fashion.” – Richard Malone

With that mindset, did you face hardships with people not understanding your work?

I think so, but I didn’t want to make it that understandable. The reality of being at the top end of fashion or art is that there are very few people who are immigrants and who are working class. That was always quite apparent to me. They were always tricky conversations. You could speak a lot about it, but people never had a certain type of empathy. They hadn’t experienced it, so they didn’t understand.

When I first graduated – and this isn’t a criticism of anyone’s designs – the only designers who were functioning were from the same area of London: Westbourne Grove or Notting Hill. Some of their mums were in the fashion industry or their aunts were famous people in fashion. Even the models were all from that area. It’s still kind of like that. All those people are just protecting their things, and not willing to question why they’re the only people in the room. There’s more diversity for sure, but not really people outside of London.

“When I started, I was 23. You don’t know anything, and you shouldn’t. I still think I shouldn’t really know anything. You should start getting to know when you’re about 60, or 80.” – Richard Malone

Did you ever feel pressured to commercialise your practice to “sell more”? Was that ever a concern for you?

It wasn’t a concern. The issue is that a lot of the prizes and awards are judged on that. I don’t think a buyer at a London department store would have any really interesting thing to say about my work. I think anything that’s based on trends is very dangerous, so I always try to avoid that. It’s funny going back through certain work because it doesn’t look like anything else. That’s one thing I’m impressed with. I didn’t want to be a designer who looks at mood boards and copies work from the nineties or noughties – I don’t think that’s smart. It’s about being transparent about what you’re trying to do, and always trying to experiment within it. If I had just done one thing, I’d be very, very bored.

When I started, I was 23. You don’t know anything, and you shouldn’t. I still think I shouldn’t really know anything. You should start getting to know when you’re about 60, or 80. It’s supposed to be a journey, a process, research, delivery, and rewarding projects. That’s how I genuinely think about it.

You’re investing so much creative energy into sculpture-making and performance art. Was it a conscious decision to move away from what society thinks fashion is in a more traditional sense?

Yes. The only reason I did shows was to get funding. There’s no other way to get funding really. With prizes and awards, I had a problem with these strange, celebrity judges. I don’t think they can judge my work because they wear anything they’re paid to wear. You have to be careful of whose opinion you let in.