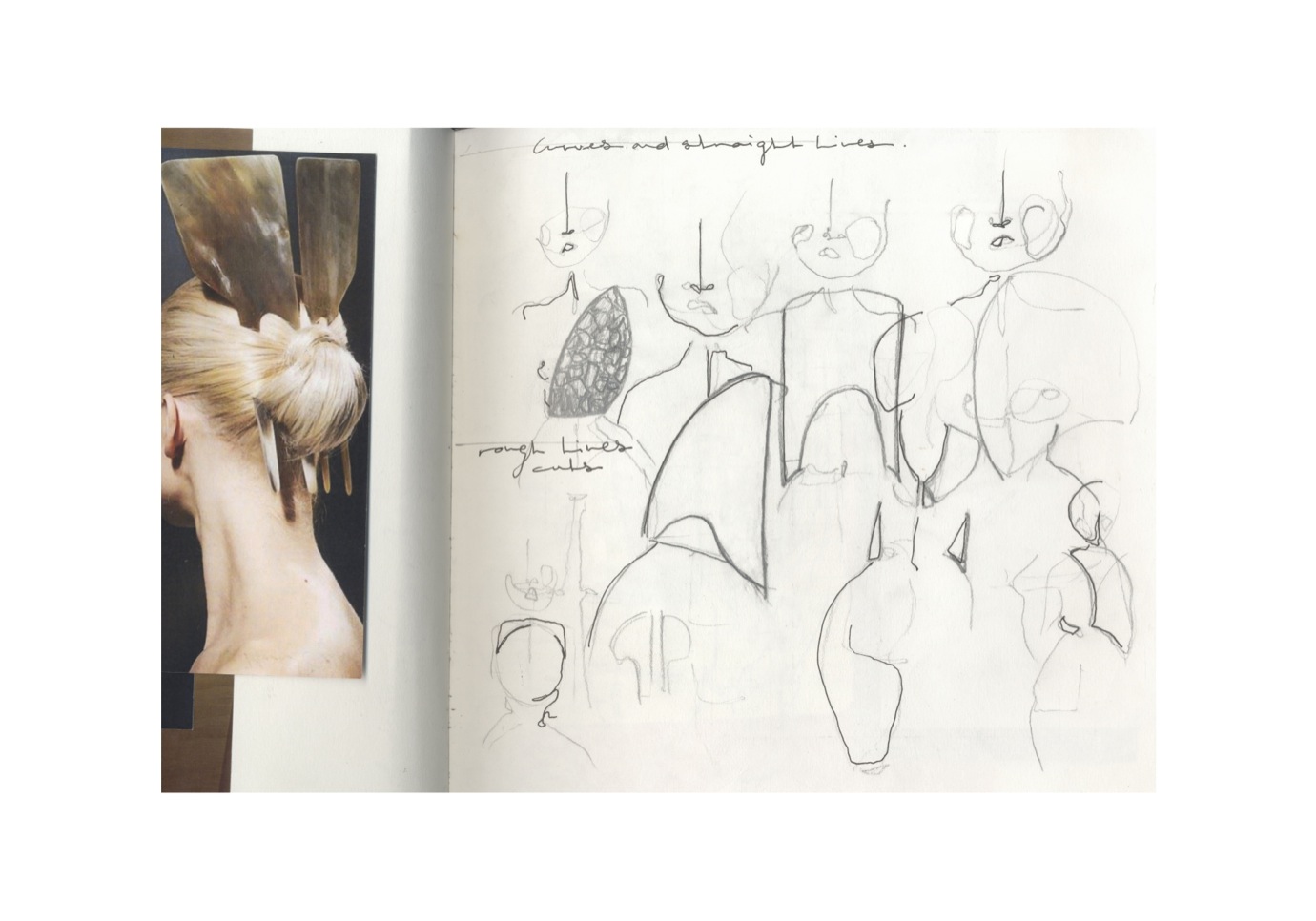

Birgit’s jewellery pieces appear as big wooden structures, almost like actual garments or protective armour; not your average jewel-set of rings and necklaces. They are still precious, however, raised above the conventions of everyday clothing: “What I find most important about jewellery, is that it can be defined as unnecessary,” she says, seemingly cryptically. “Unlike clothing, a person doesn’t need to wear a necklace or a bracelet. Therefore, the wearer makes an absolute conscious decision when s/he puts on a certain piece. The irrelevancy can expose the personal and intimate.” Combine this with an unconventional freedom in use of material, and jewellery seems to be one of the most open forms of practice – its expanded field of conceptual investigation along with an attention to materiality and the wearer. “There’s just one main importance,” she adds; “that there is always a close connection between the body and the piece.” For Birgit, everyday wearability is a not a concern, as long as there is some form of interaction with the wearer. Primarily, she uses her jewellery practice to explore uncommon materials within jewellery.

“I FOUND IT INTERESTING TO SEE HOW A SUBJECT CAN BE REDUCED TO ITS ESSENCE AND STILL KEEP ALL ITS STRENGTH AND IMPACT.”