What was the conceptual starting point of your graduate collection?

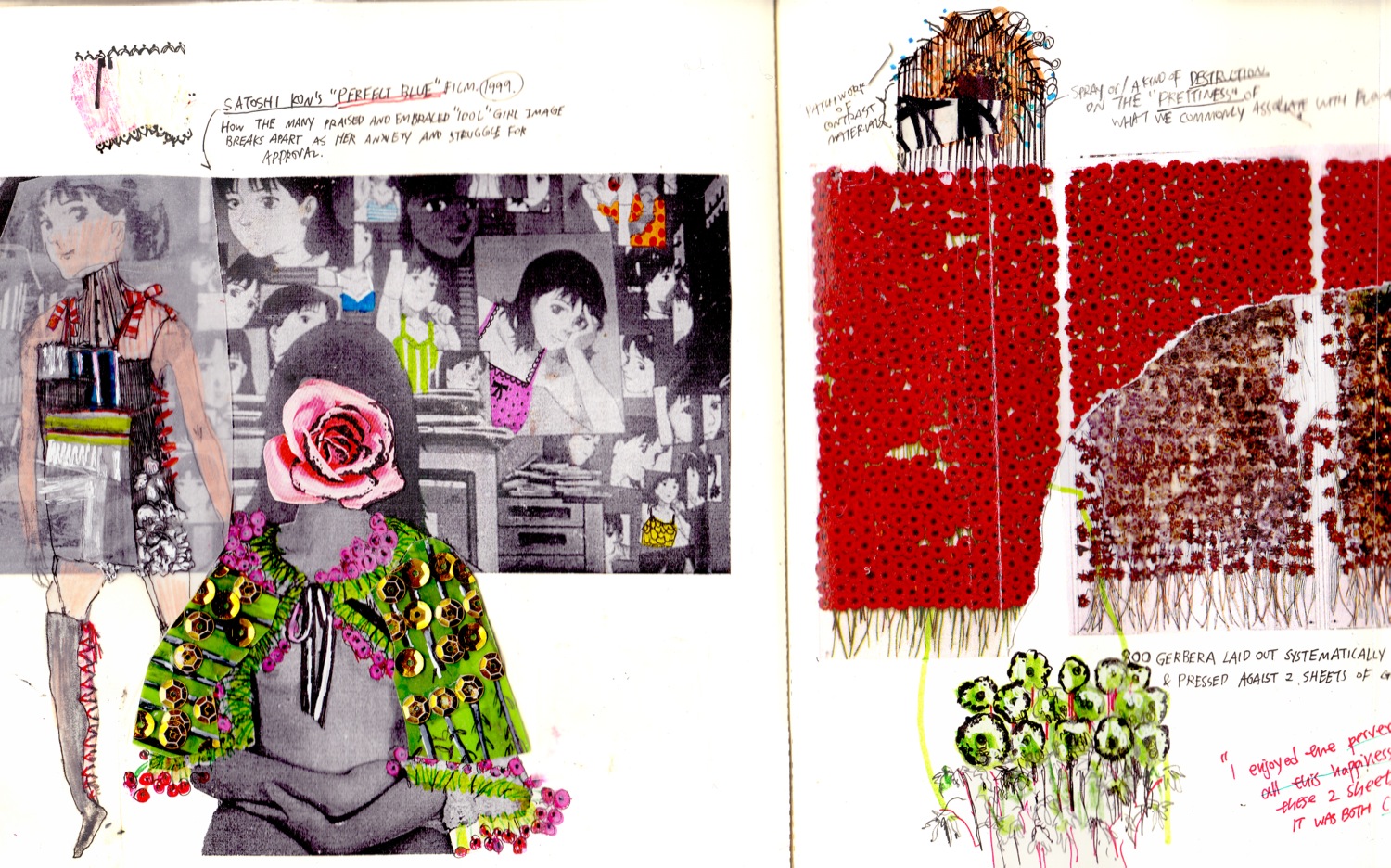

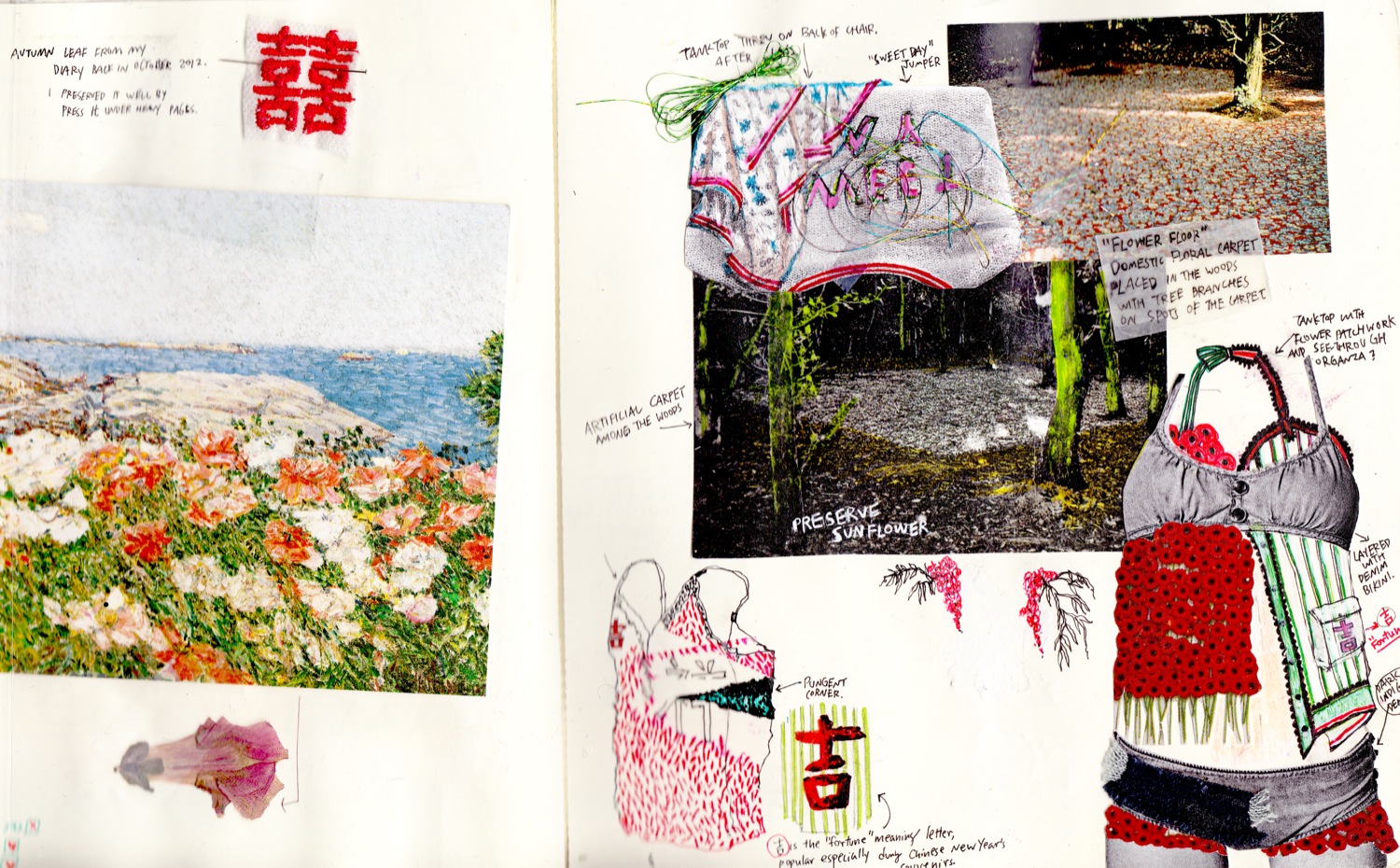

During the summer before final year, I visited my grandparents in Taiwan and joined them to refurbish a countryside garden that was passed down by my great-grandfather 60 years ago. As I walked along the garden path, there were crushed petals scattered all over the muddy ground. Ran over by footsteps and vehicle wheels, they were withered and had quietly sunken down into the earth. I found that the flower, as it blooms and decays, has a degree of romance and unease. Each flower’s mortality is so unique, there will never be another stem decomposed and crumbled down the same way. I was very inspired by Anya Gallaccio’s ‘Preserve Beauty’ installation, composed of 800 fresh gerberas laid out systematically in grids and pressed in between sheets of glasses. During the period in which it was displayed, the flowers withered and died, and this decay process was visible to the viewers through the glass. In one of her interviews, Gallaccio expressed how one “loses authority over the material” due to the characteristics of nature, and the unexpected quality in the transience of life. I think the flower offers a contradictory degree of perspectives. The flower is a well-recognized symbol, popularly seen in fashion, common and very available to the public. It could be seen as randomly beautiful, cliche, or even mundane. In fengshui and Chinese cultural myths, symbols of jinx like the withered flower, which is perceived as a symbol of bad luck and foreshadows a woman’s misfortune in classical Chinese literature, and the number 4, which has the same pronunciation as death, are consciously avoided. This paradox led me to focus my final collection around these ideas.

How do you create a visual narrative out of an abstract concept?

It was challenging to translate the conceptual idea of feng shui and taboos into visual narratives. The process of narrating my cultural memories and childhood experiences was very vague at first, but at the same time, one’s memories are so abundant and unique. I began seeing visual narratives in my head when listening to elders back in Taiwan, who talked to me about their experiences growing up, and the myths they’ve encountered during their lives; like how bridal couples were dressed head to toe in red as a symbol of prosperity, or how kids were taught not to leave a single grain of rice when dining so they would marry a good spouse. As I began seeing life through other people’s perspective, I started to accumulate the visual ideas for my collection.

How did your collection develop during the course of the year?

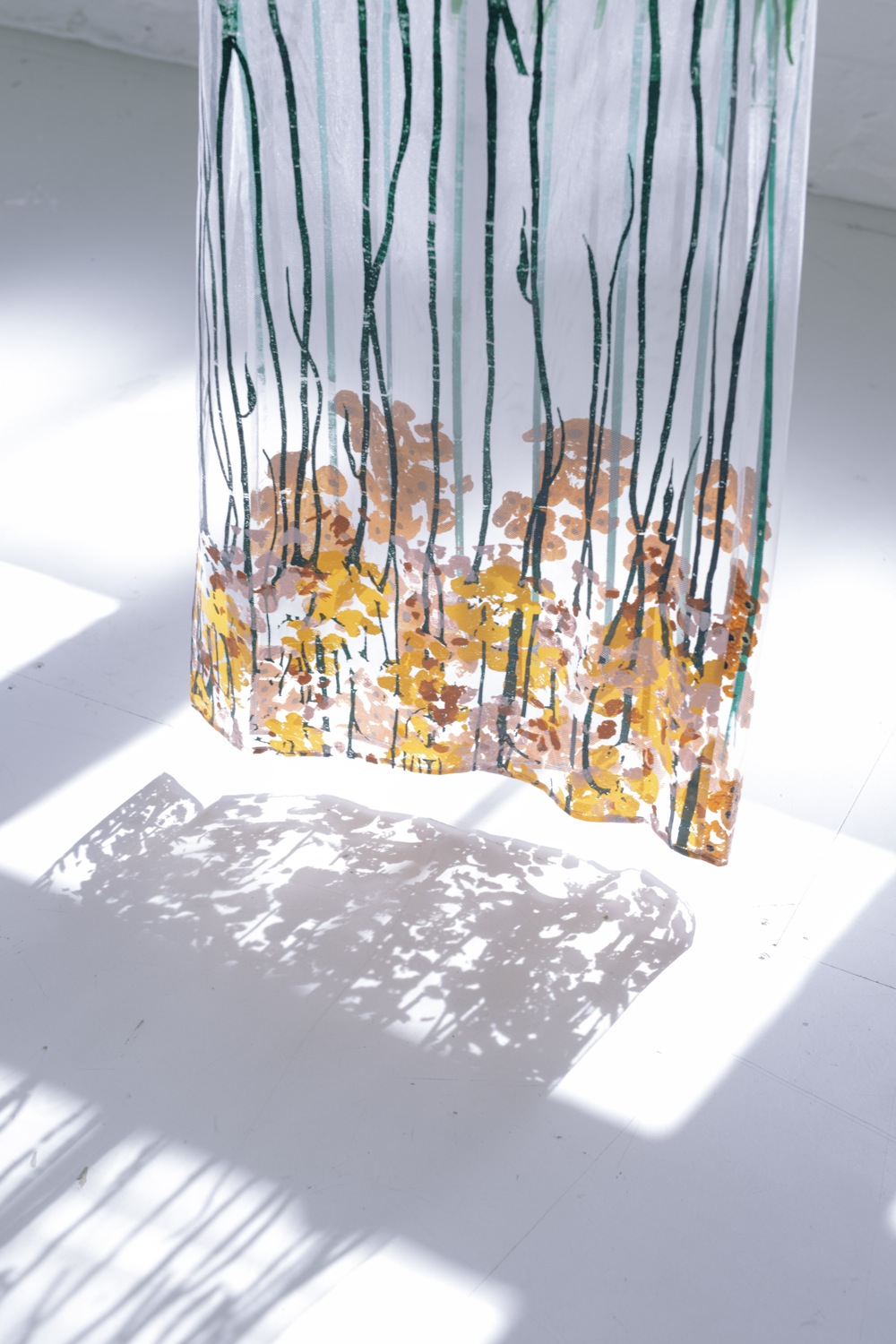

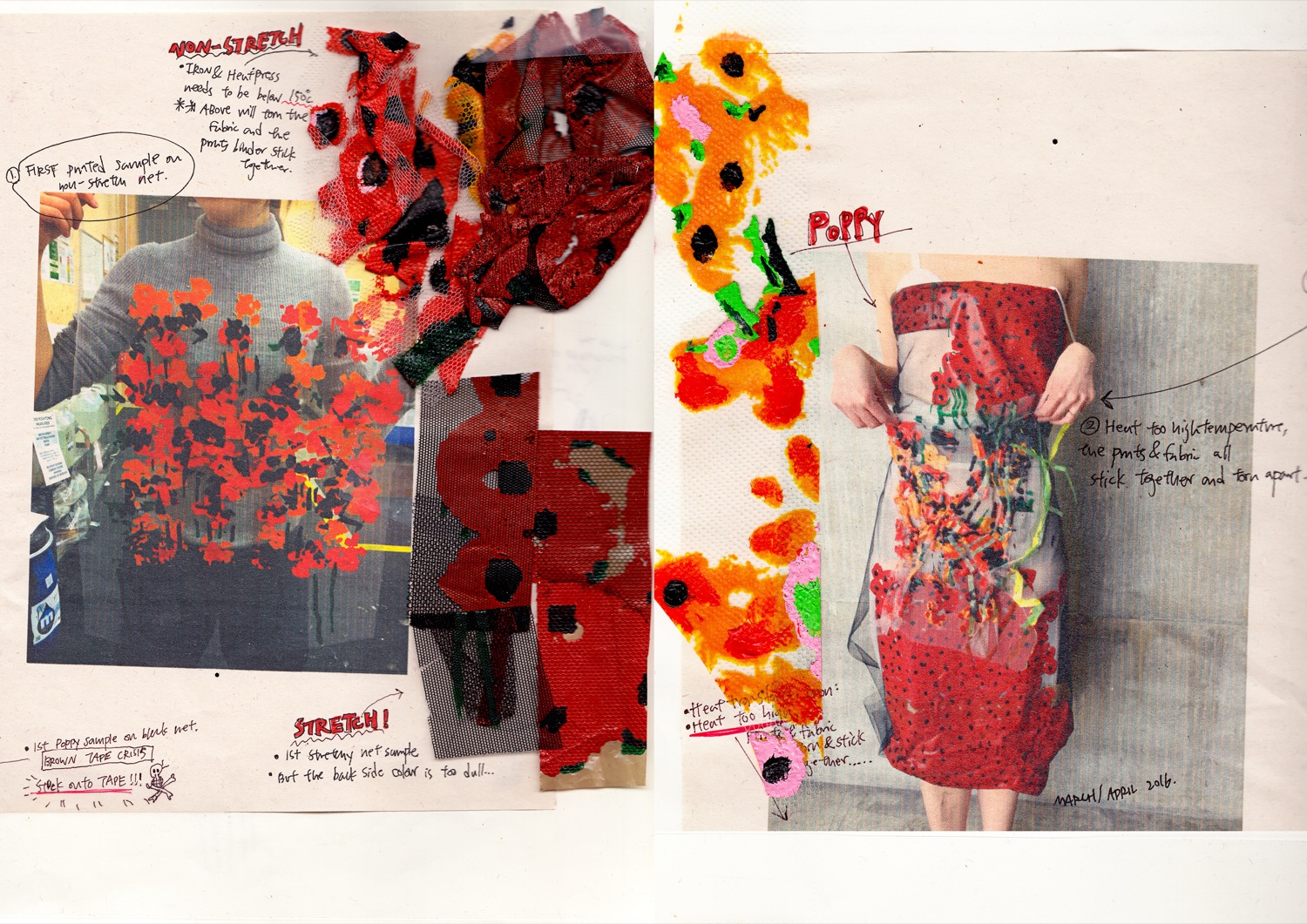

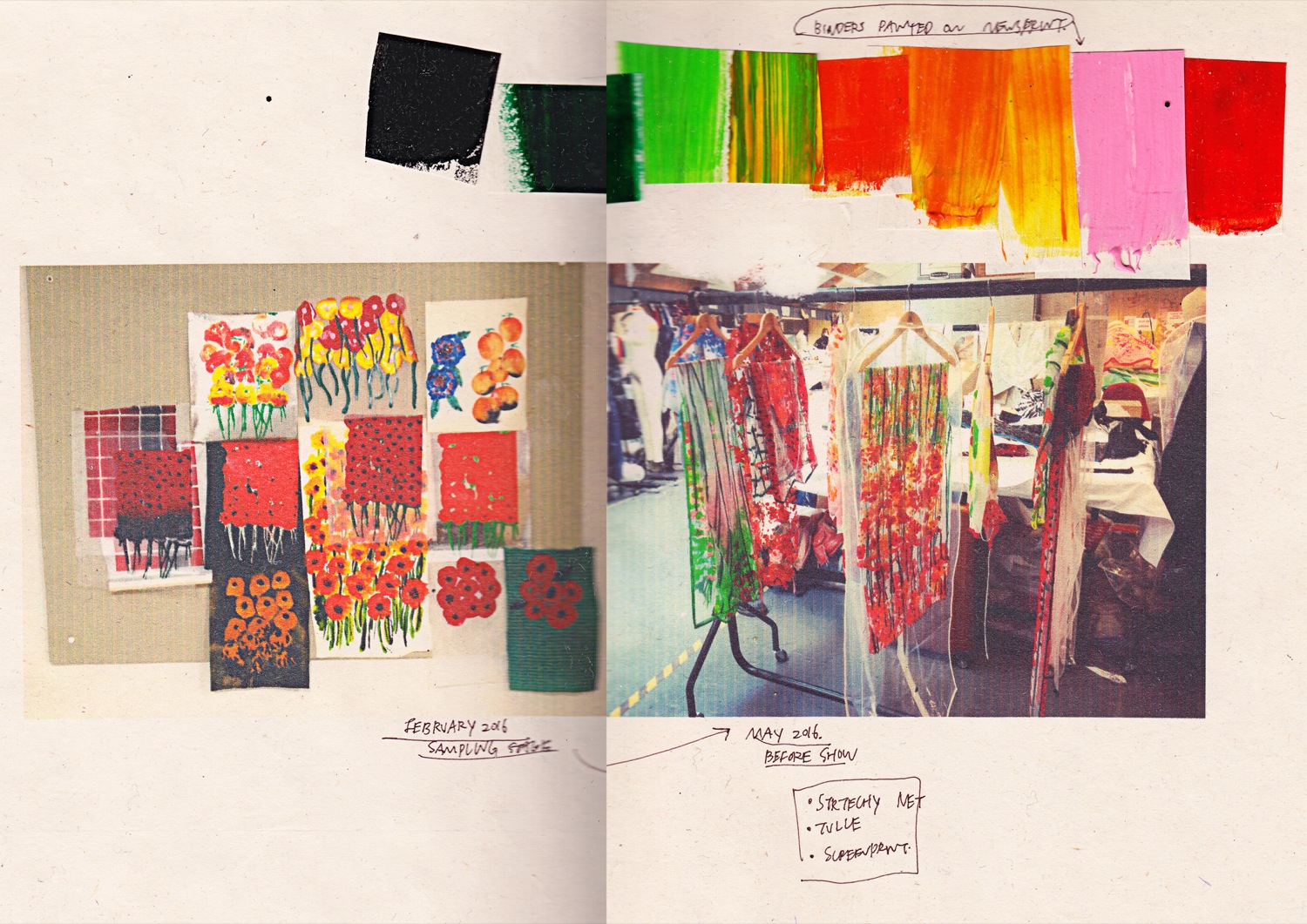

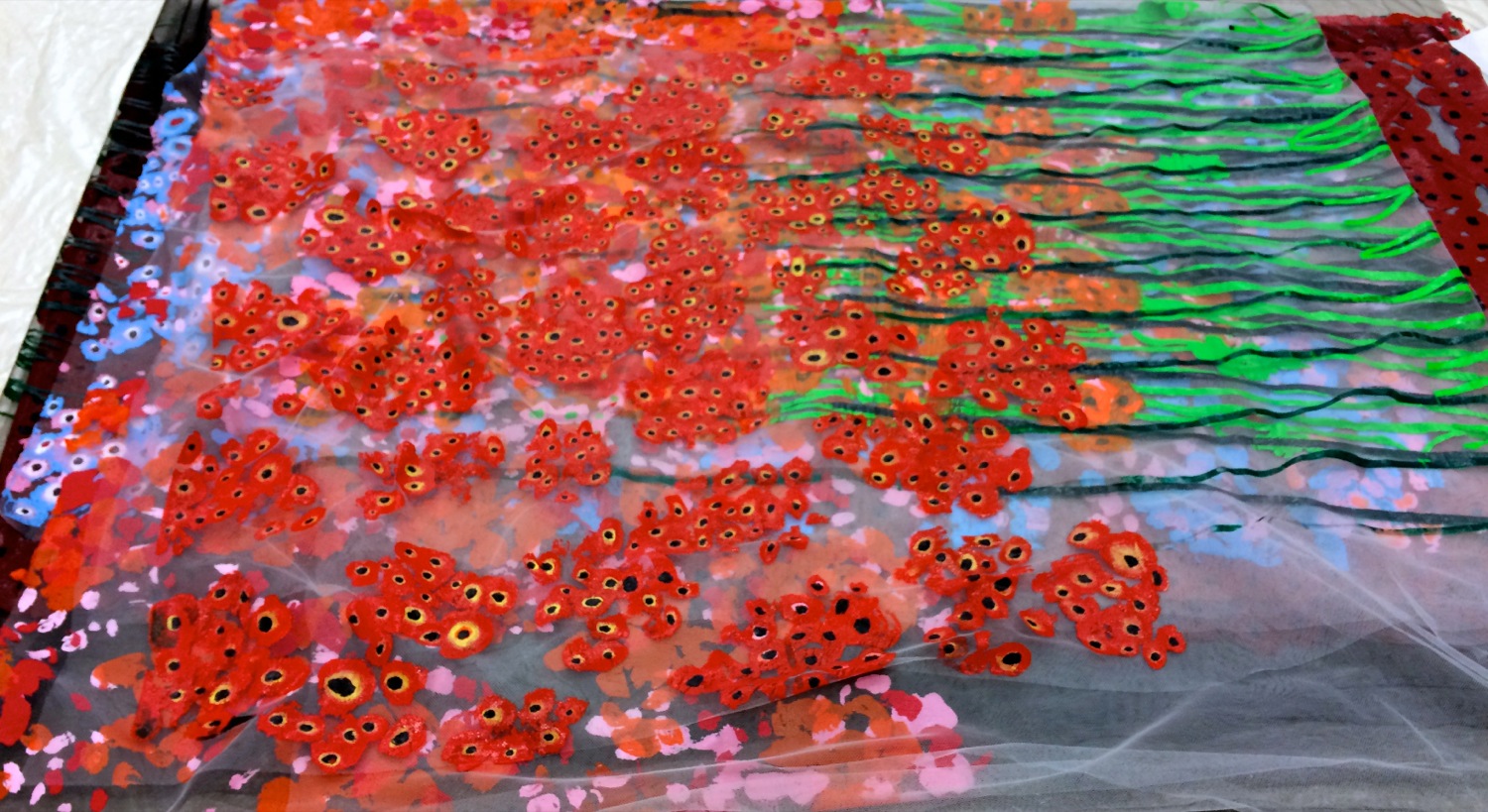

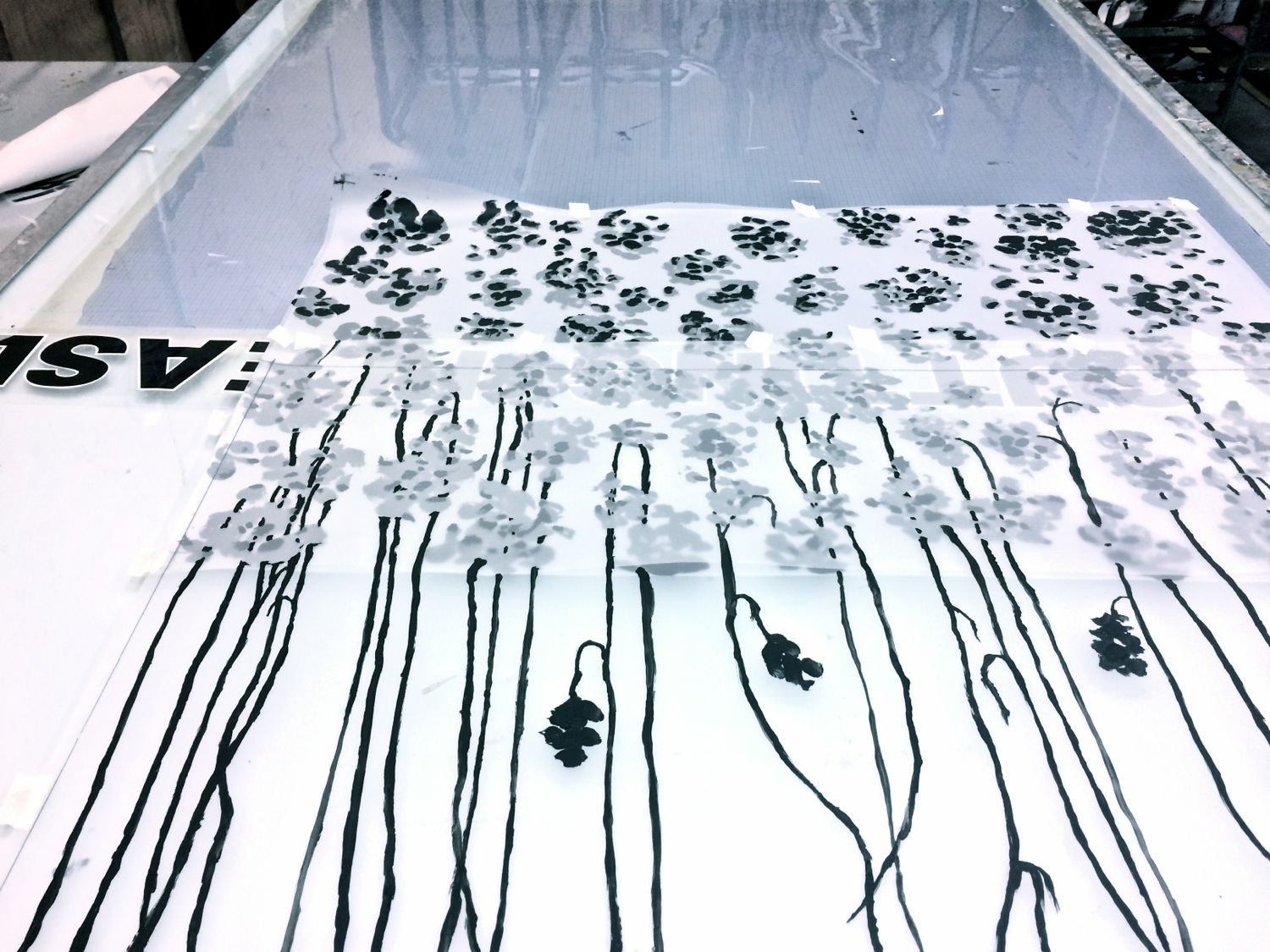

My collection encountered quite a lot of issues throughout the year. One of my most memorable challenges was during the fabric development stage working in the print room. Before finding the solution to maintain and treat the fabrics, my printed fabrics used to stick to each other like a melting meatball. I remember at one point an entire piece of two metre long fabric stuck to itself. The print room technicians, as well as my helpers, each held a corner of the fabric and tried our best to stretch it out, whilst my tutor was heating the fabric back to its initial state. It was a very hardcore experience having both helpers, tutors and technicians helping me rescue my work.

What does your development process usually look like?

It focuses a lot on working in sketchbooks and making illustrations. Especially I enjoy drawing directly on toiles and white garments; it helps me to think about garment constructions. I also like to get inspired by looking at fine art installations, paintings and books before I begin to sketch.