“I kept on facing new problems each minute. At one point I wasn’t even surprised anymore. I really learnt to ‘complain’, be patient, undo and remake.”

What was the conceptual starting point of your graduate collection?

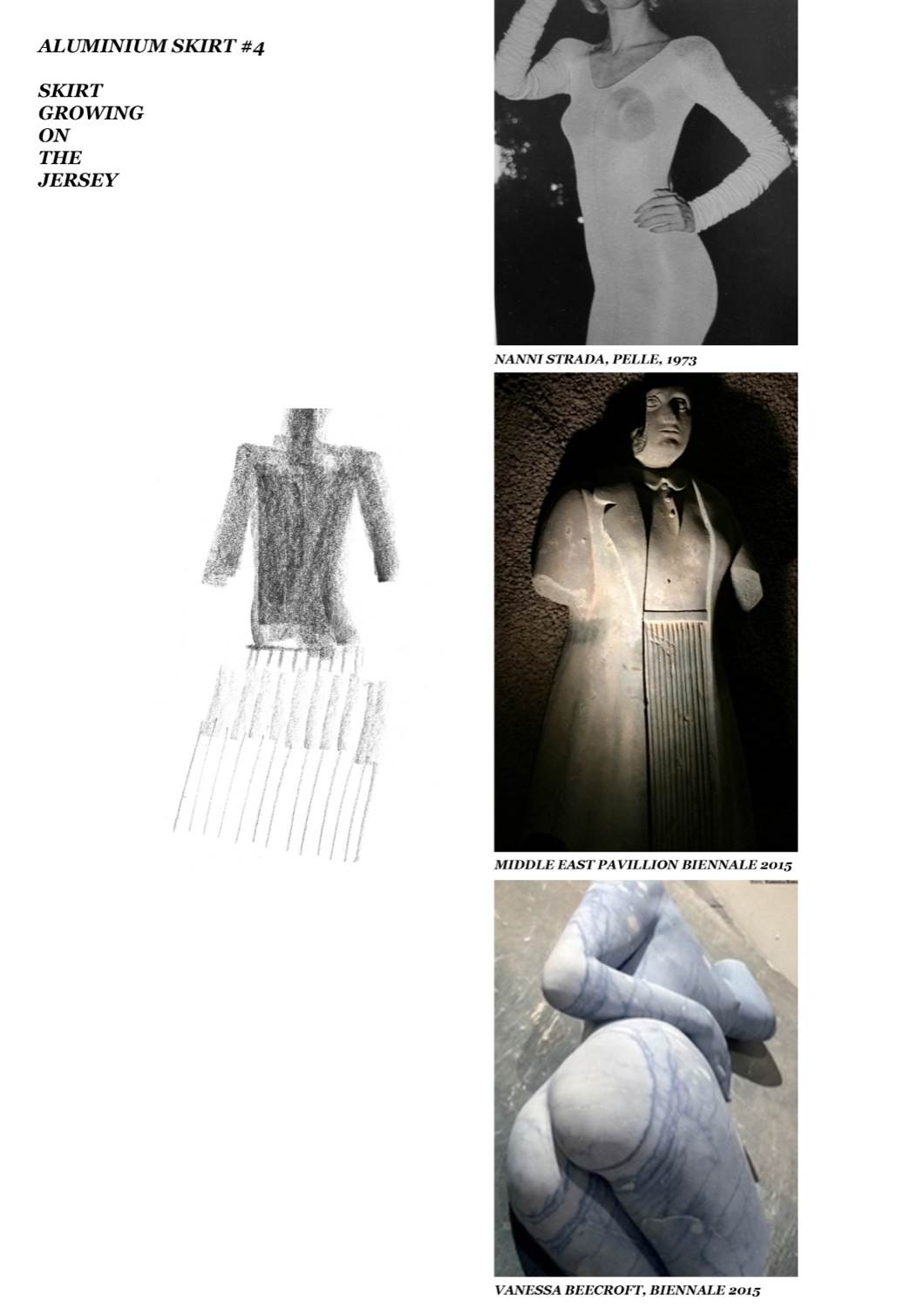

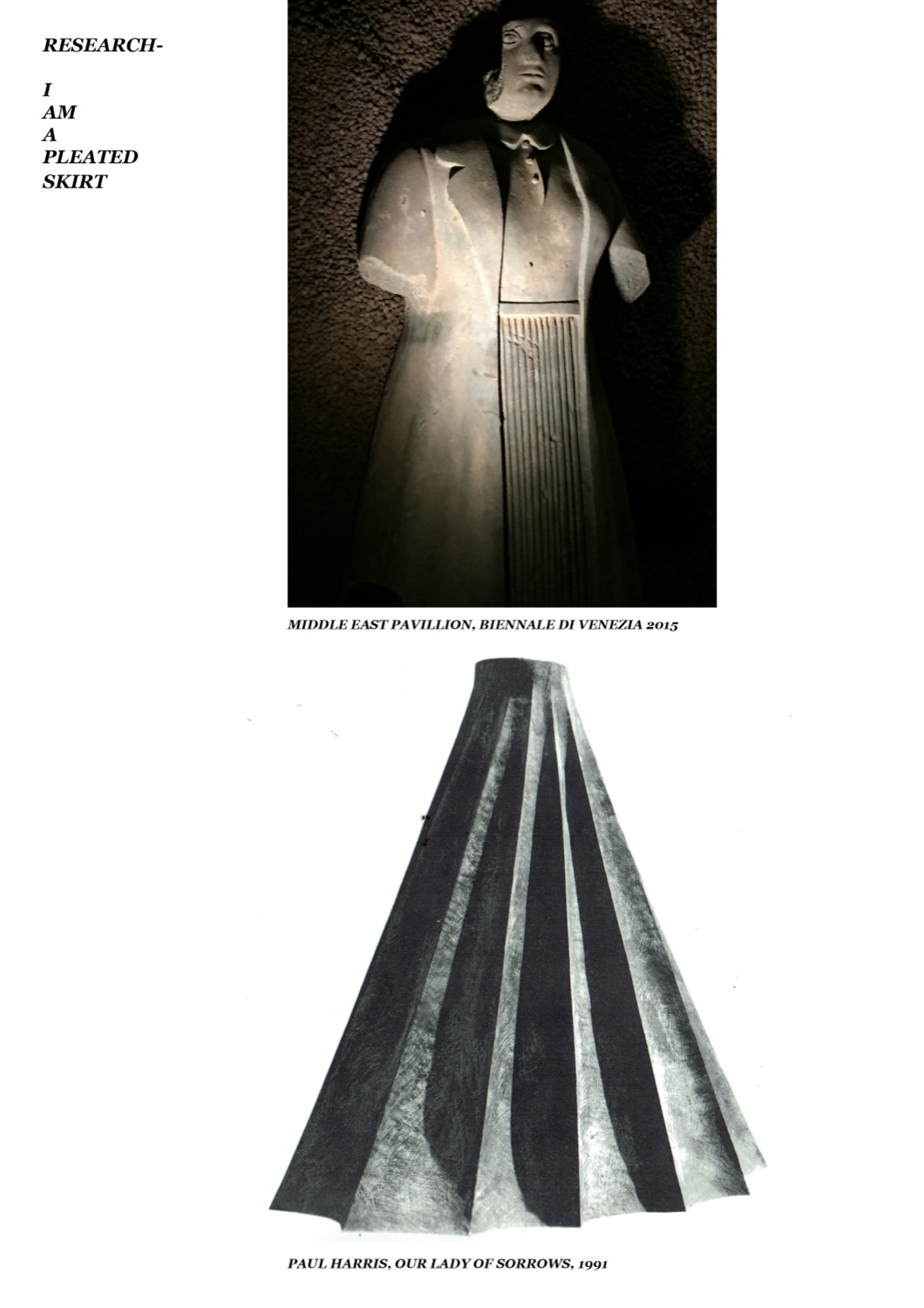

I started doing research on everyday practice and performance, and read about the more mundane and unexplored aspects of clothes – which is the daily relationship we have with garments. Virginia Woolf, Louise Bourgeois, Joanne Entwistle and Umberto Eco were my main resources. During my placement year I was taking pictures of what I was wearing, how I was matching colours and fabrics, the lengths of the garments and their weight. In a vintage market I found a peach, pleated, polyester skirt (which I used as one of the outfits in the show). The seriousness of the pleats contrasted the frivolous aspects of the peach colour and the cheap fabric, which I thought represented me quite well. I started to question my particular attachment to this skirt and to some of my clothes, and why I wear them continuously. The idea of the collection came together when I visited Vanessa Beecroft’s installation at the Venice Biennale last summer; I like how she always creates powerful images around the concept of repetition. In addition to that, the beauty of her marble torsos evoked a softness, and the overall impact was classic and contemporary. Everything I had gathered so far – the pleated skirt, the sculptural element, the softness, the colours, the identity, the performance element of repetition and the every-day aspect – finally just merged into one single vision.

How do you create a visual narrative out of an abstract concept?

The visual narrative usually comes together quite naturally, since all the research I collect is according to my own aesthetics. I have two big mood boards where I push my images around and split them up into areas of development, which gives me a panoramic view of my idea. The main design feature of my graduate collection is the idea of the gap between the body and the garment, which manifest itself in the sculptural skirts. The big challenge though is how to translate the conceptual into something wearable. Before starting final year, I remember that I wanted to have both show pieces and more wearable versions of them. I’ll have the time to explore the potential of my ideas into a fully wearable collection during my MA.

How did your collection develop during the course of the year? Did you face any serious challenges during the production process?

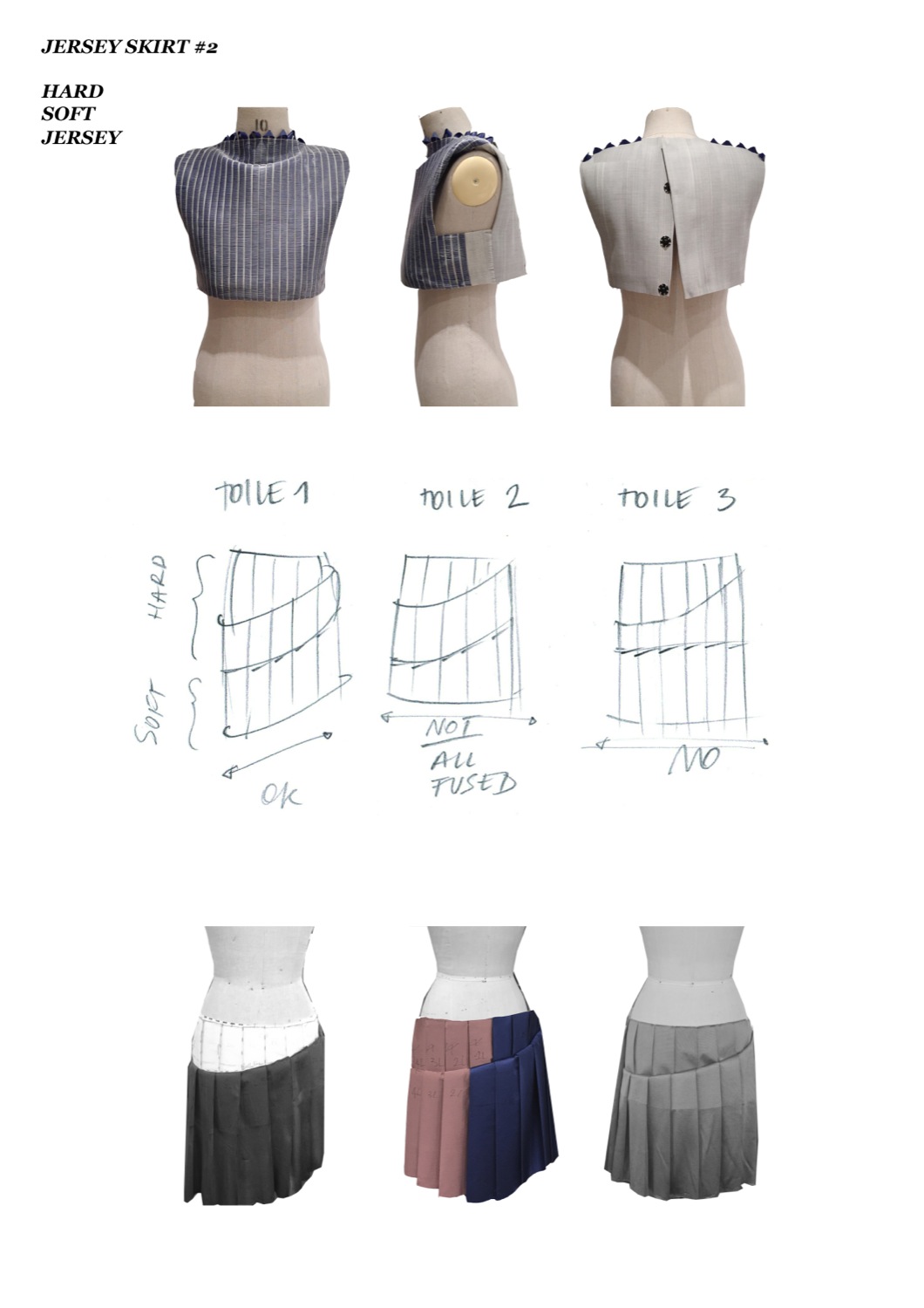

The idea got to me pretty quickly and looks quite simple. I did a lot of experimentation in the first term and edited my ideas down a lot later on. But sometimes I would look back at the first idea again, just to try and keep the simplicity of it. When it came to the production, the wearable pieces were as hard to make as the metal skirts. The actual making didn’t take that long, compared to the time it took to master the techniques. For the aluminium skirts I worked with an Italian metal workshop, who generously sponsored the project. I had to make a real size cardboard model and an autocad file for each skirt. They tested several weights and thicknesses, but the skirts were always too heavy. Only 2 months before deadline they found a roll of 0,3 mm aluminium and, with no trials, they made the finals straight away. It was hand-pleated with a special folding machine and sprayed with several layers of car paint. It stayed in the oven for 2 hours; like a proper car. I also faced a lot of challenges when it came to the layers of fabrics surrounding and supporting the metal pieces. The jersey layer on top of the skirts needed several passages before being mounted with screws inside the metal pleats. To make the skirts stand far away from the body I had to make asymmetric paddings, etc… I could go on forever, I kept on facing new problems each minute. At one point I wasn’t even surprised anymore. I really learnt to ‘complain’, be patient, undo and remake. Asking for advices is also important! The exchange of thoughts between me and my team of 1st and 2nd years was a huge contribution to the collection and they found solutions I didn’t think of. Having students helping you is a big responsibility, and their work is the result of your management skills.

Do you get inspired by every project/brief?

All the projects are quite open at CSM, so you can always find a way to relate to them. My advice, when you get stuck, is that you should ‘think simple’ and not over complicate your ideas. Go back to the starting point and your first intuition. Ask yourself questions, and maybe try to find a solution to something that already exists, but needs improvement.

What does your development process usually look like?

At the first stage of development my work is instinctive and playful, I just enjoy the process. In the second stage I try to contextualize the direction of the idea and name it. Shortly thereafter, I explore if what I imagined can work in 3d and try to work out the technical aspects of the project. Of course, at some point you have to stop developing and finish the work. But even when I know what the outcome is going to look like, I keep myself open to possibilities. Sometimes it adds to a last element that completes it.

How does the conversation between 2D and 3D work for you, how much does one inform the other?

In both cases you can use them to explore or refine an idea. You can use drawing as a way to explore your imagination, like when we were kids, but also to resolve your designs more efficiently. Draping is again both intuitively creative and playful, but at the same time you’re able to carefully consider volumes, proportions and technical solutions. Seeing my ideas on paper usually makes them a guideline for my 3D work. The 3D approach completes my ideas from the practical side. It is also useful to sketch after draping, since you can unlock solutions and refine your ideas even more. They complete each other and tend to merge when I work, depending on what I think is required for the moment. I would suggest to develop both skills, as fashion companies use different methods when they work, and you should be able to adapt to their requirements.

Do you feel that your collection somehow reflects who you are as a designer?

I definitely think so, maybe it represents who I was when I was making it. I really felt the need to demonstrate who I was. I created one specific concept that I repeated several times over. 12 girls, 12 skirts, 12 slippers. It was a performance in a way, I found myself and it represented my aesthetics very clearly. Now when it’s over, it feels like my past; not my present or my future. Having done that, I feel the next stage for me is to open up to the outside world; to contextualise my work within contemporary society and react to it, in order to propose something relevant.

Being critiqued constantly, sometimes we can lose sight of who we are or what our work stands for. Where would you draw the line between growing from those feedbacks and conforming to give tutors/clients what they want?

The moment you try too hard to make everyone happy is probably the moment you’ll lose yourself. I know my work can’t be appreciated by everyone, and I accept that. Personally, whenever I feel I’m losing the vision of my work, I only confront myself to the people I trust – a couple of tutors who’ve followed me from the beginning, a few good friends and my mother. I take feedback from people who have the right experience very seriously, and try to contextualize the critique according this person’s background and perspective. This makes me evaluate my work from a different point of view and improve it. But at the end it’s you who has to be the one to make the final decisions yourself.

What did you do during your placement year?

I interned in Paris at Sonia Rykiel for 6 months and at Maison Margiela for 8 months. At Rykiel I learnt how to work efficiently, which I adopted to plan my final collection. It’s a very organized, friendly company and the designers are really focused on the fit, the cut and the comfort. Margiela was a surreal experience. I loved the building in Belleville (once a monastery, then primary school), and not to mention the archive… Interns have a very special role, and creatively we contributed a lot. In comparison I had more responsibilities at Margiela and was actively involved in every aspect of the collection.

What advice would you give for students choosing their placements?

Don’t be picky! The placement year is a full time learning process, be willing to offer your help wherever you go.

What are your plans for the immediate future?

I have a place on the MA and few special projects on the side.