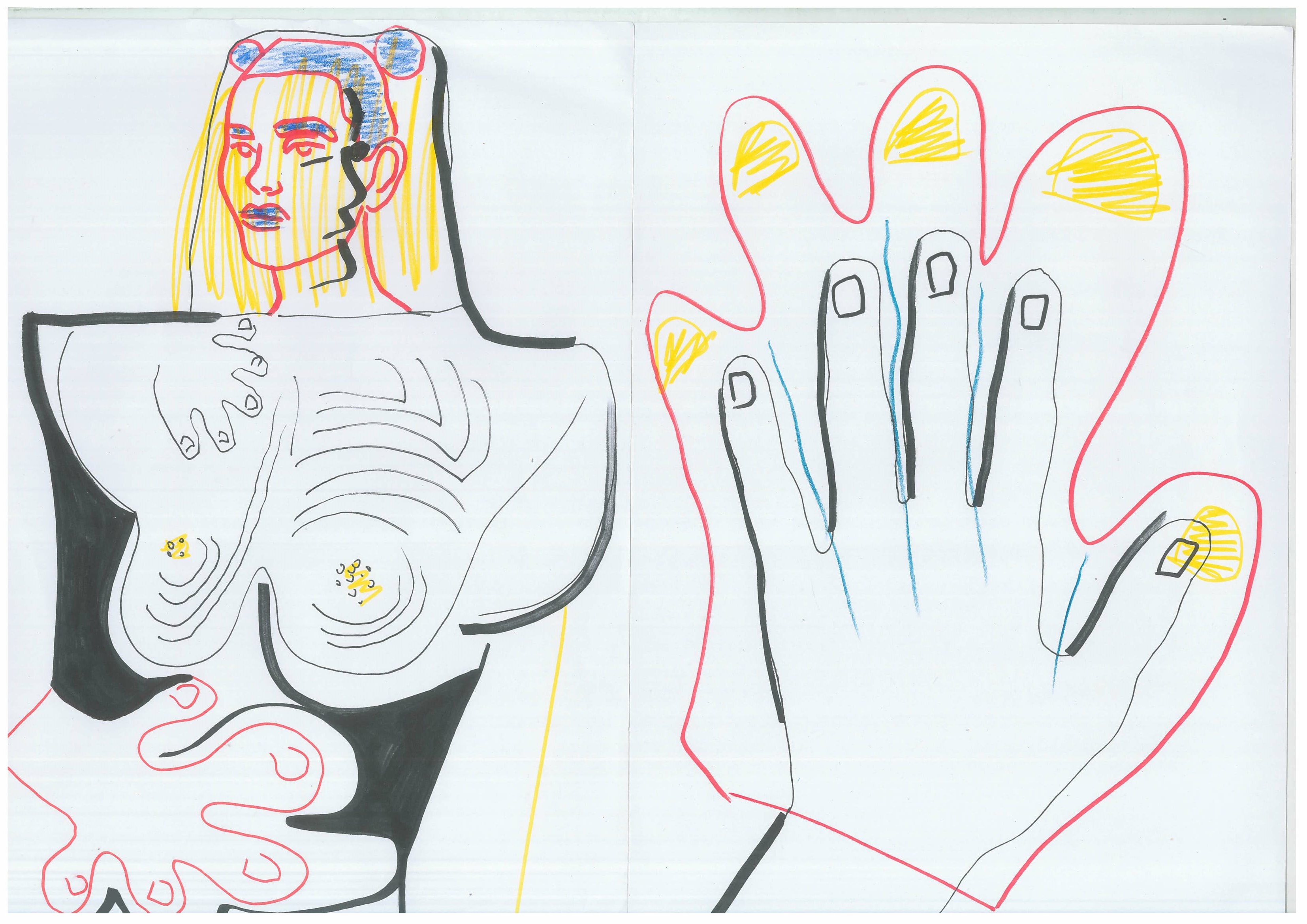

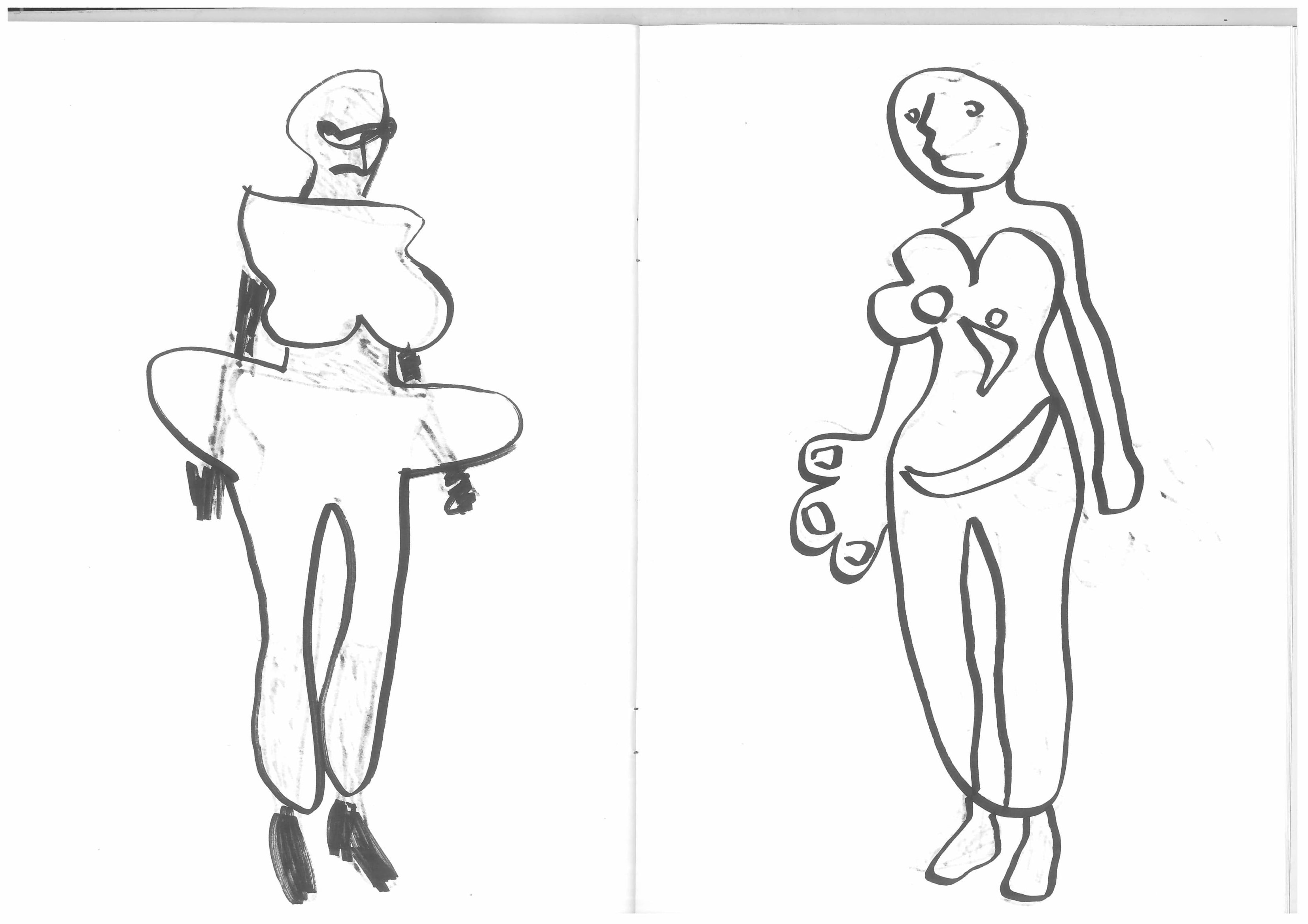

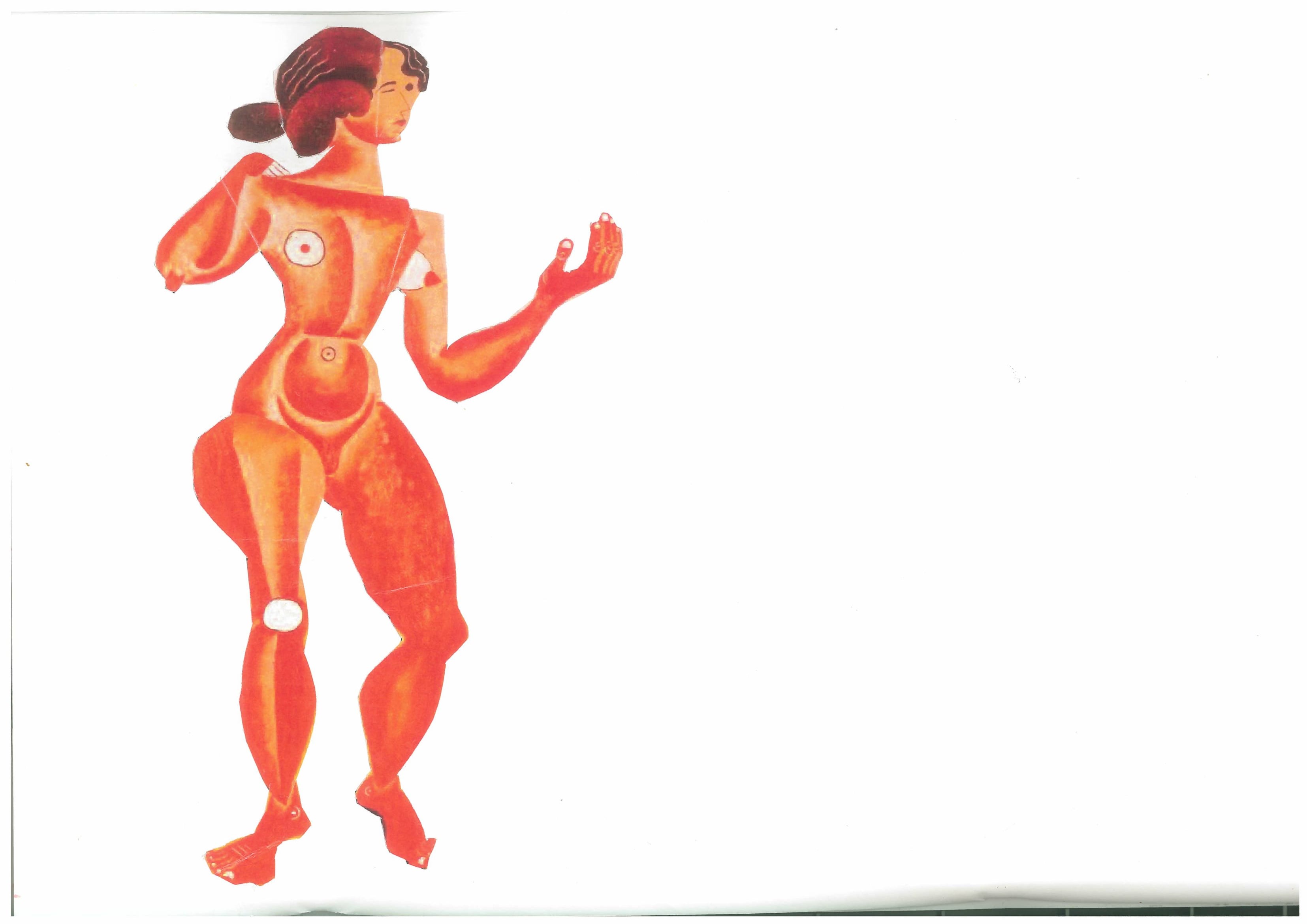

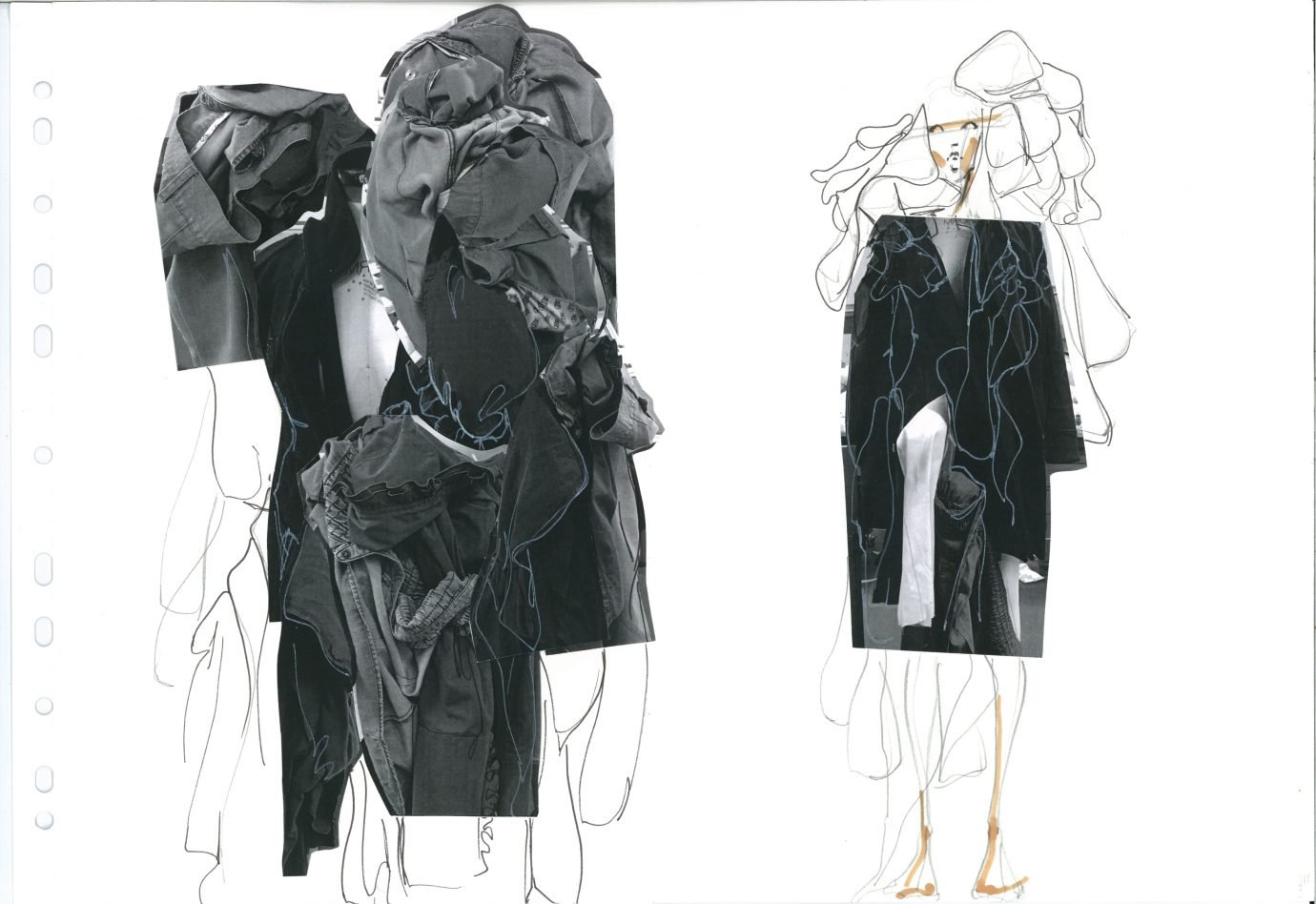

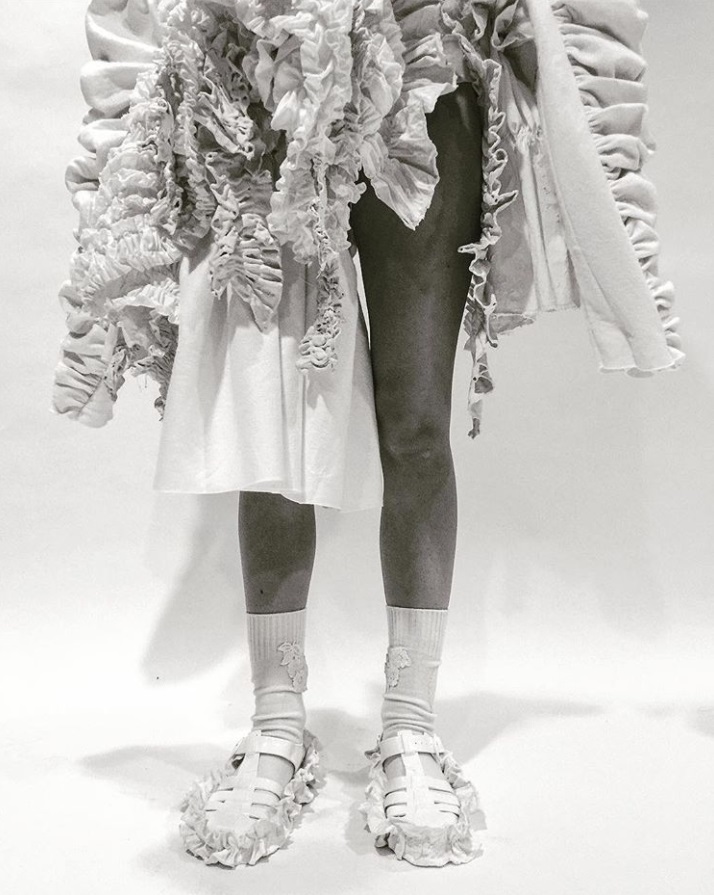

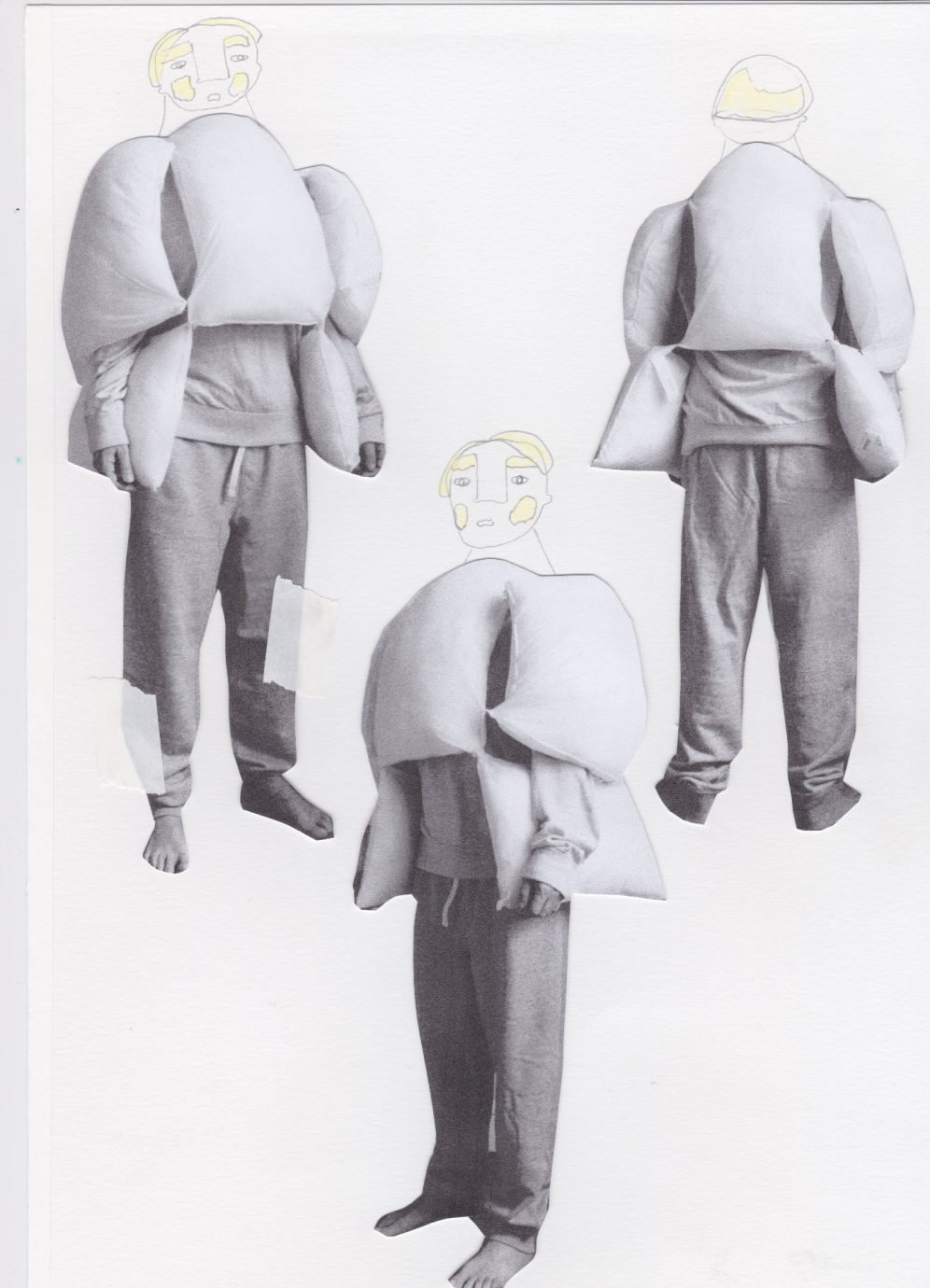

The silhouette, like the petals of an orchid, is delicate yet bold. The fabric stiff, the body’s sex adorned pearlescent. Repetitious minutiae almost make the skin crawl. Asymmetrical cut-outs are slotted together. The double cup over the stomach guides the eye back and forth between the model’s breasts and her navel; the bareness of her skin is striking. An oversized padded hand juts out to the left, beyond the extrusions of the exaggerated waist. Whilst behind, the backs of the legs are cut out, exposing the fragility of the construction. The overlapping curvilinear shapes are those from Miró’s painting, The Tilled Field.

These iconographic features reference the cultural heritage of medieval Spain – the muted palette of tapestries, the stylised animals of frescos – whilst in the top left hand corner, the French, Catalan, and Spanish flags display a political engagement. The opposition of the flags (French and Catalan on one side of a tree, Spanish on the other) defies the Spanish dictatorship and boldly states Miró’s Catalonian allegiance.