Rebecca grew up in Manchester in the north of England, where she spent her childhood years designing, dreaming about costumes, and creating visual characters for her friends and pet dog. In 2008, she came to London in after finishing school to acquire a one-year diploma at London College of Fashion and continued immediately at Westminster for its fashion degree, but took the decision after one year to transfer to Womenswear at the neighbouring Central Saint Martins. “I was attracted to the lack of restriction within CSM and I wanted to be surrounded by people and talent that would make me question and challenge my work and myself,” she says as she recalls her first days at the institution.

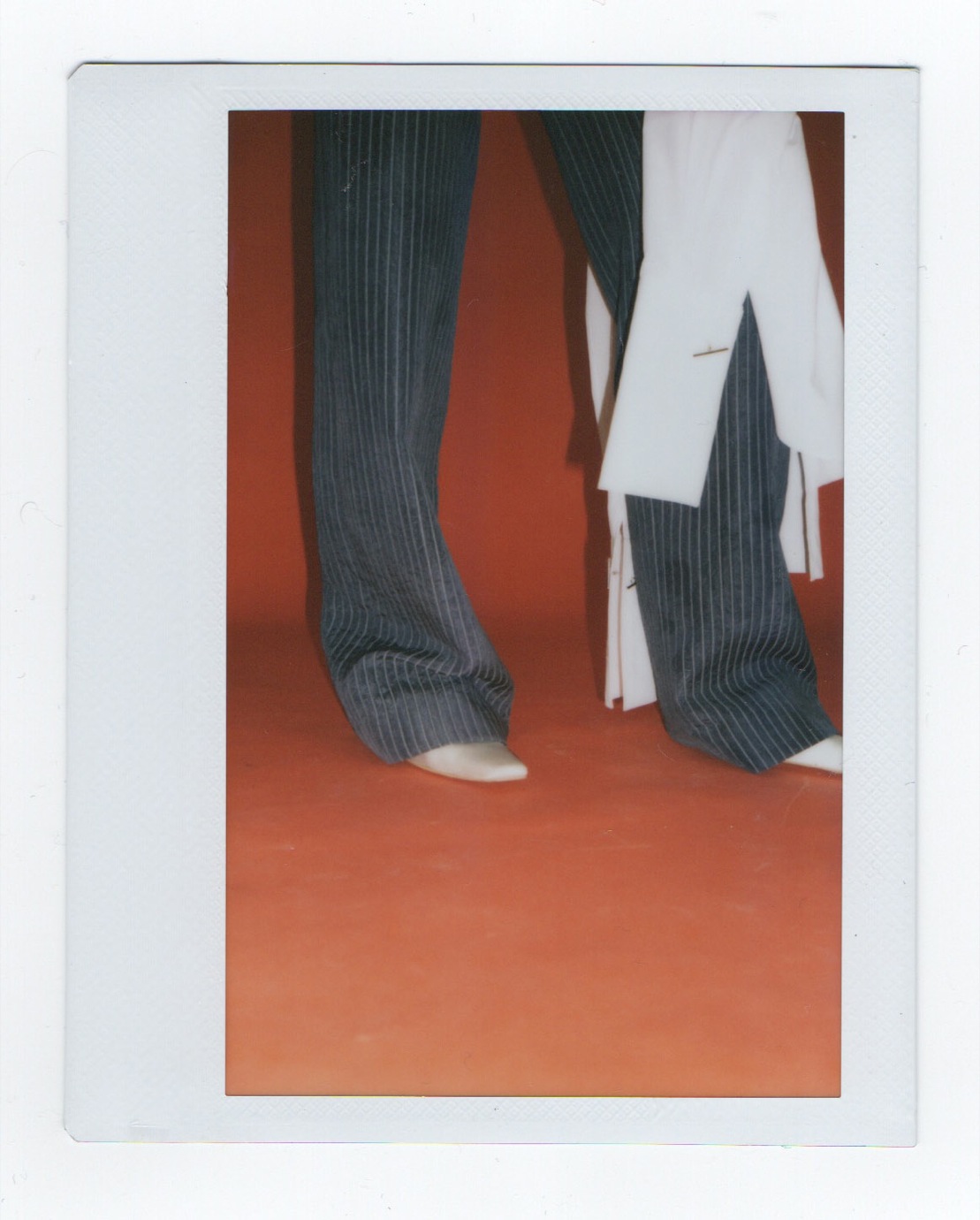

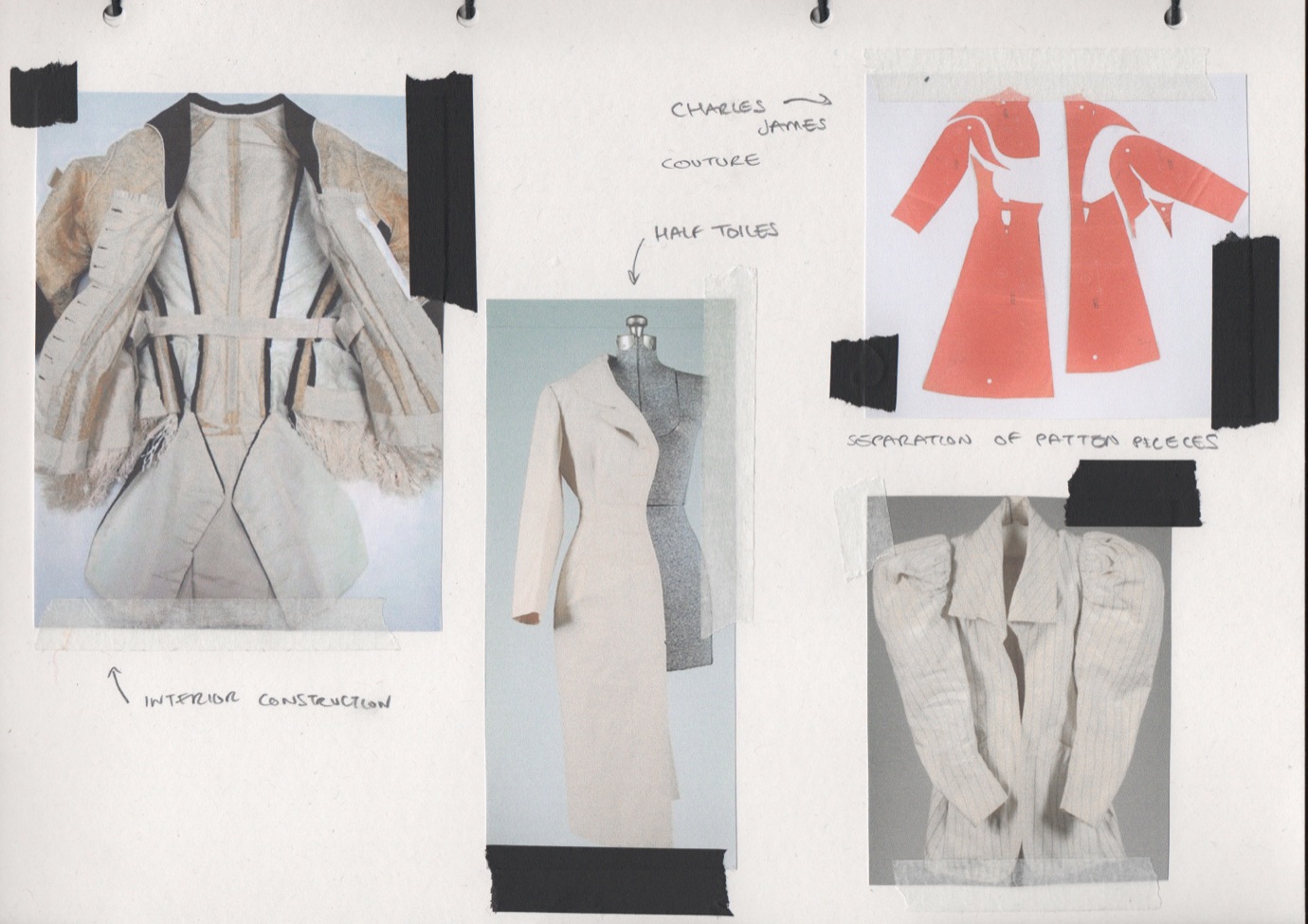

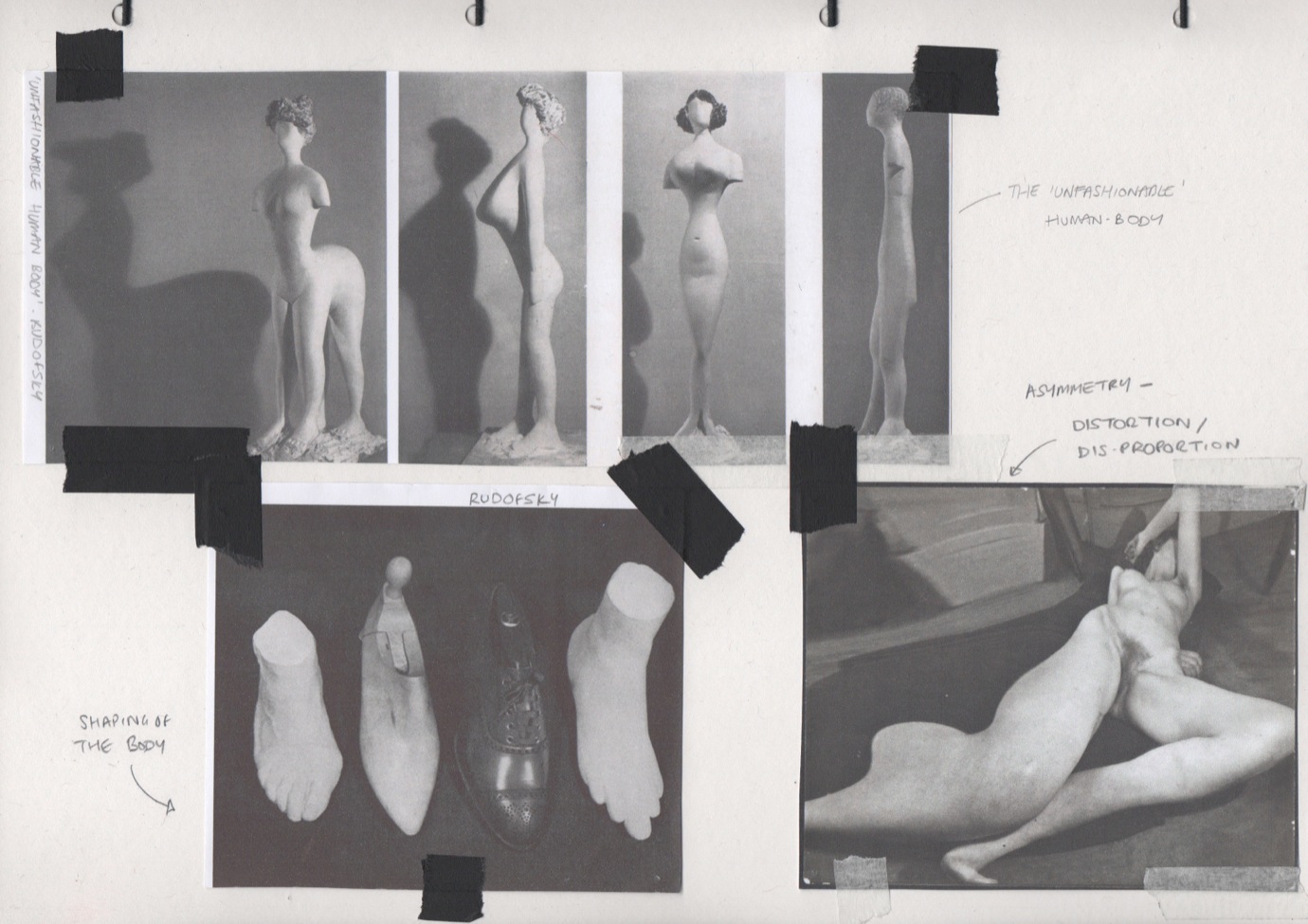

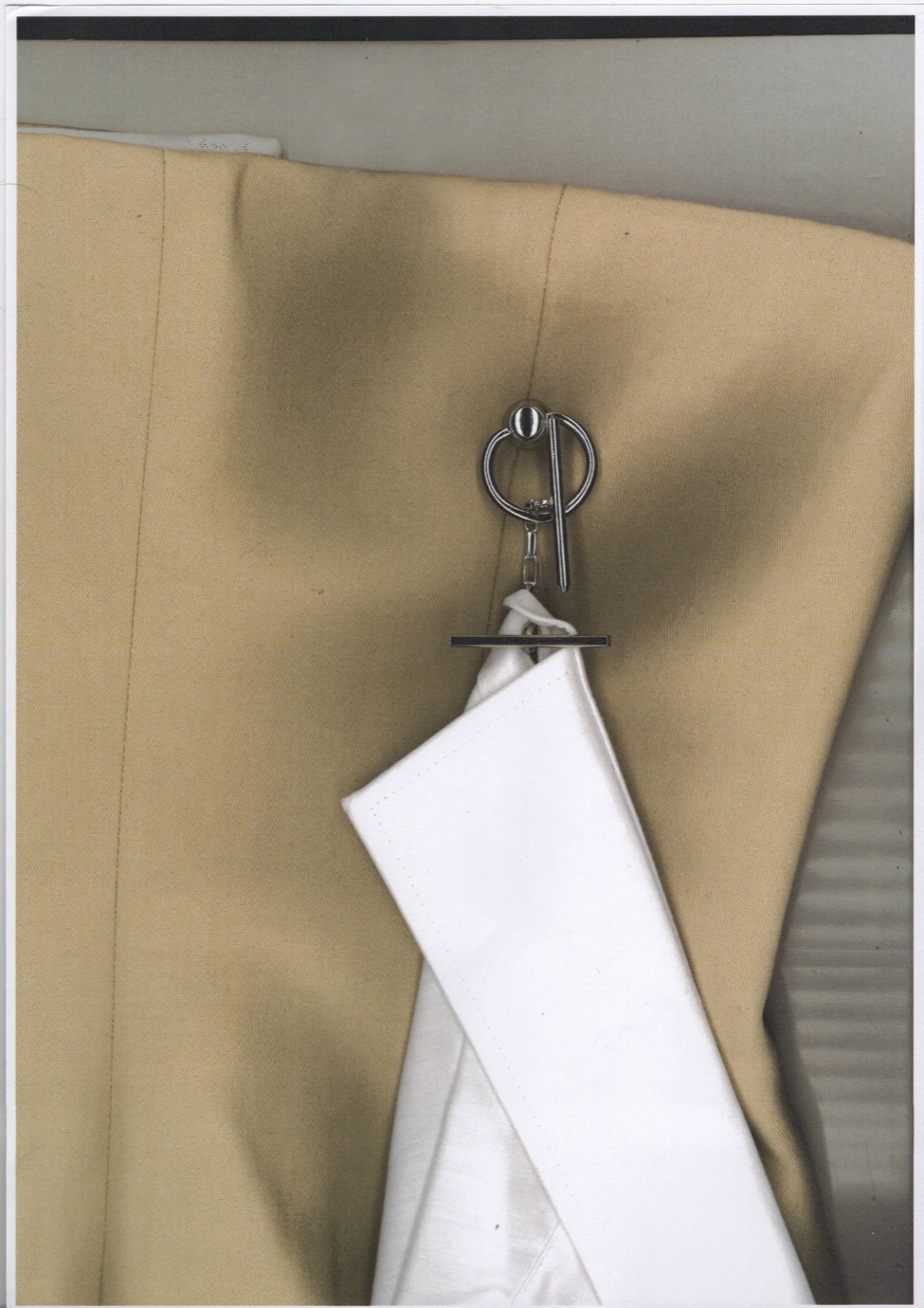

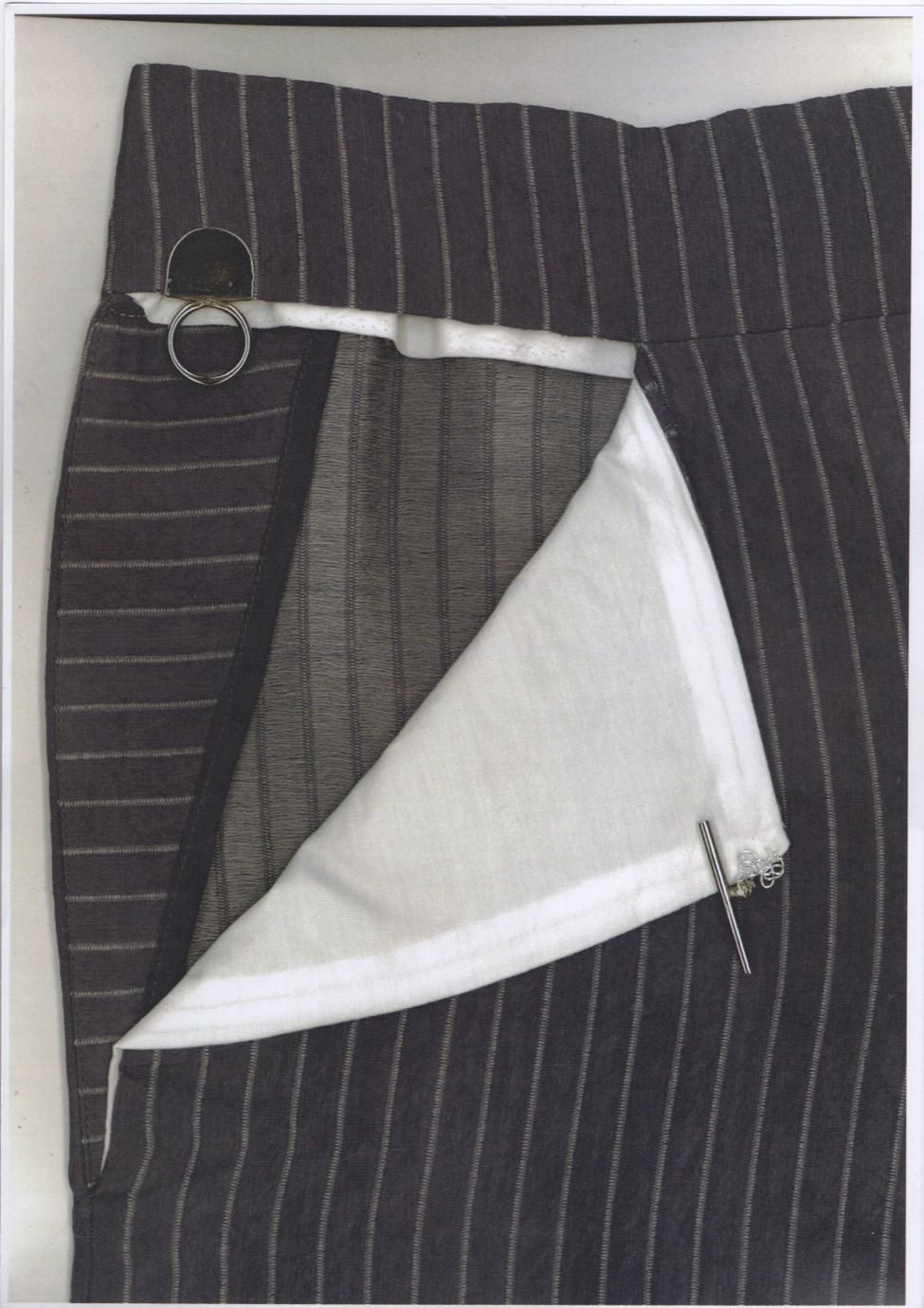

Rebecca’s research circulates around fundamental questioning of the basics of clothing and body: the justification of the cut and construction of garments, their asymmetric interaction with the body, the complexity of the female form. “I’m interested how clothes have been built around the body throughout history, and the various ways in which we have attempted to shape it,” she explains. This led her to discover the work of Benard Rudofsky, the Moravian artist and architect who in his work sculpted figures and body parts as though imagining an underlying shape of the body in a humorous yet poignant way. Inspired by this idea of distorting the human shape, Rebecca collaged together a timeline of corsets (fashion history’s biggest distortion of the human shape) from 1800-1900, to develop a series of asymmetric obscured silhouettes. “I came across images of pregnancy and maternity corsets, with lacing that could be released as the pregnancy developed and openings with a clasp on the breast for feeding. It just seems insane now, but it really struck a cord,” she explains.