In one of the previous interviews in this series, 1 Granary spoke with Westminster’s fashion course director, Andrew Groves, about the fact that the late Louise Wilson’s influence seems to have been far greater on those who have become tutors, as opposed to her reputed influence on fashion designers. When we ran into Linda Loppa at the LVMH Prize cocktail reception in March, it was an opportune moment to investigate her impact on those whom she’s taught.

She was the head of the Royal Academy of Art’s fashion department in Antwerp for 25 years before being appointed as dean of the Polimoda International Institute of Fashion Design & Marketing in Florence in 2008. She gave the reigns to Walter van Beirendonck, whom many believe has been taught by Loppa (as he was part of the Antwerp Six), but less is true.

“History can be deceiving,” Loppa reflects. “What is correct,” she continues, “is that in many fashion schools all over the world — from Chicago, to Vienna or Tokyo — graduates of the Fashion Department of Antwerp are now leaders in education. My 45 years experience in different fashion fields, not only education, taught me that if education reaches its goal, it could change a person.”

In 45 years, she has undoubtedly taken more different routes through the fashion industry than most of her contemporaries. She graduated from the Royal Academy in 1971; worked as a designer for a Belgian outerwear company where she specialized in producing raincoats; launched a high-end boutique in 1978 that sold fashion from designers like Jean-Paul Gaultier, Helmut Lang, Comme des Garçons; was the head of the fashion department at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts for twenty-five years. These jobs were often overlapping. During the years as head of fashion at the Academy, she founded the Flanders Fashion Institute and the ModeNatie forum in Belgium. It is fair to say that Loppa has been extremely instrumental in the development of Belgian fashion and its global recognition.

“The industry is using designers in a very bad way; they overuse them, change them, drop them or mismanage them. It is time to give a voice and time to designers, so that they can grow slowly in the concept and philosophy of the house.”

She is now positioned as an influential educator in a country that is not well known for pushing young talent. However, Loppa is not concerned about Italy’s future in the fashion market. “Emilio Pucci just hired a young Italian designer, Massimo Giorgetti. The world of fashion is global, but the authenticity of the heritage and the origin of the designer cannot be ignored.”

‘Creativity’ means different things for different people, and in an interview with The Florentine, Loppa mentioned: “Creativity is not about the newest sleeve, it’s about finding solutions. That’s what the fashion business needs right now. It’s about your strategy, your vision, your branding, and your communication. Leading the world of fashion is more important than making a beautiful garment.” What solution does she think the fashion industry needs at this very moment? “The industry is using designers in a very bad way; they overuse them, change them, drop them or mismanage them. It is time to give a voice and time to designers, so that they can grow slowly in the concept and philosophy of the house. Designers are not commodities, but human beings who have the right to make errors and reflect on the fashion system, even criticize it if necessary.”

It’s daunting to be truly creative when a fashion designer needs to produce more than four collections a year, which is the unfortunate reality today. Designers who have their own labels also run the risk of drowning under an even bigger workload the second they’re hired by a large conglomerate who appoints them as creative directors for one of its fashion houses. It’s quite contradictory. The industry squeezes the last drop of creativity out of designers until they’re bare and empty shells that are ready to be discarded.

“If the results on the latest catwalks in Paris were not strong, that’s what I heard and saw during Paris Fashion Week, all the players in the field should ask themselves some questions.”

What advice does Loppa have for those who want to be successful on their own terms as fashion designer without being shacked by the growing number of seasonal collections each year? “Designers have a voice. Even if they are well paid, does it mean that they can express what they feel? I am sure that many suffered from the pressure of two months of shows, showrooms, parties, and up to the next section of [sourcing] fabrics for pre-fall or pre-summer. If the results on the latest catwalks in Paris were not strong, that’s what I heard and saw during Paris Fashion Week, all the players in the field should ask themselves some questions. The best designers are Japanese because they are not listening to the critics and continue to do what they think is important for fashion — following creativity!”

One of the initial 26 shortlisted designers for the LVMH Prize 2015, Yoshikazu Yamagata is an example of this Japanese creativity. He doesn’t necessarily put the focus on doing what the industry wants. Loppa was one of the international experts who came down to Rue de Montaigne to talk with the nominees; see their works, and make a shortlist of the eight designers she thinks should win the €300,000 prize. Designers like Yamagata don’t necessarily have the business know-how, and might need to find the balance between commerciality and creativity in order to grow and expand their brand successfully. What would she recommend any international fashion designer who doesn’t know anybody in the field of business? “Playing safe is the worst position for the fashion industry and for fashion in general. LVMH should award the most experimental designers and help grow these businesses (this is, of course, just my humble opinion); the designers focusing on easy immediate success are not going to last long; they have short-term vision.”

“What became a new movement in the postmodern era now becomes a fast collage of ideas that are remodeled without inspiration. What’s missing is content, structure, long-term vision and new aesthetics…ideas.”

Vision is the key theme that runs through Loppa’s career like a red thread. The Antwerp Six, whom she’s often credited for teaching, were known for their radically new vision in the eighties. A lot has changed since then. Radicalism on the runway has almost disappeared entirely today. Is it simply harder to recognize, now that technological innovations have become the focal point? Radical or not radical, fashion critics are increasingly noting the lack of newness. Designers are referencing the past more, and becoming postmodernist in their approach. In an interview with A Shaded View on Fashion, Loppa mentioned that she saw an exhibition on postmodernism in London and was amazed by it. What’s her stance on this movement in fashion? “Postmodernism was born thanks to collage, re-construction and error. I didn’t see that while I was living the postmodern moment, because I didn’t quite like the results, and this is the same for today’s fashion. What became a new movement in the postmodern era now becomes a fast collage of ideas that are remodeled without inspiration. What’s missing is content, structure, long-term vision and new aesthetics…ideas.”

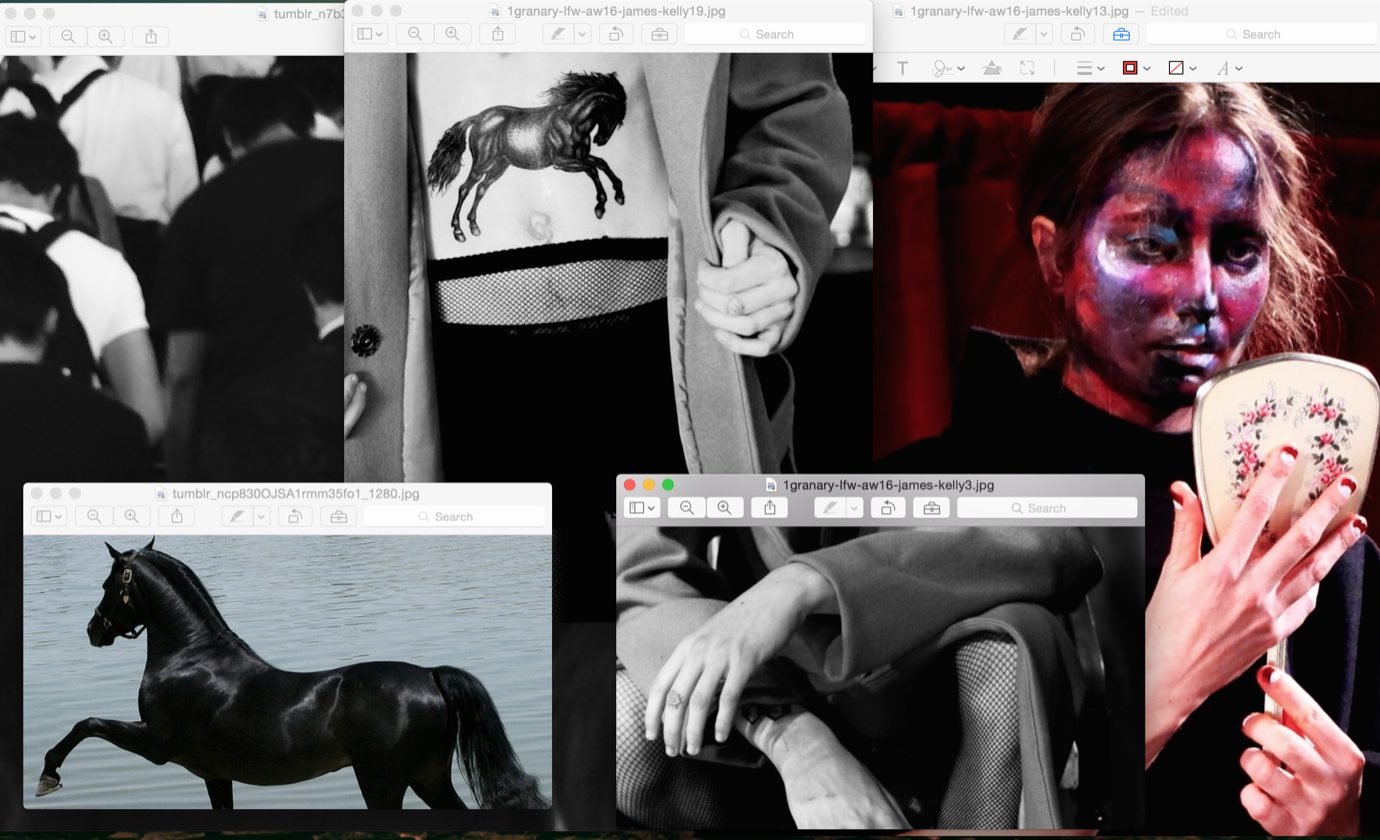

The Internet has democratized fashion and expanded its reach tremendously, while Tumblr culture has facilitated a designer’s postmodern approach to inspiration. The winners of the fashion game are often great self-promoters, so what does Loppa instill in her students about self-representation without losing integrity? She oddly mentions Kanye West: “He’s the new pop designer. I enjoyed his show that was styled by artist Vanessa Beecroft. I don’t teach in classrooms anymore but I talk a lot with my head of departments, and what we understand is the importance of art direction in collections. This is not a new phenomenon — all the fields surrounding the artefact or garment have always been important; those fields are photography, styling, imagery, messages and mood, space and time, research or craft. Looking at the focus or the priority of the designer, these elements are important because they bring balance to the brand and collection.”

Loppa is a manager, visionary, dreamer and humble sensei. And while she’s not teaching directly in classrooms, her influence is definitely dispersed in good chunks around the globe, and instilled in those who have been touched by her. The name Linda Loppa has become synonymous for grafting talent, but what would she rather want the world to talk about, when her name comes up in a conversation? “That I am a builder of bridges.”