“Not everyone can do runway. It’s a digital world.”

Shelley Fox glances across the table towards the bar, inside an Italian restaurant blocks from Union Square. “You can’t water up, but you can water down,” she utters. The logic is so simple; it’s one that works as well with mixologists as with designers, despite the fact that the latter certainly grapple with it. “As a designer, you can always make things commercial,” she says by way of explanation. And while there are plenty of those quick to cast New York as a city with an eye for money but little flair for creativity, Fox is out to flip the script. The British-born director has, in recent years, challenged the New York fashion world, promoted it, given it new energy, and acted as sort of a bellwether to the city’s new generation of designers. While others are in fashion for the thrill of each season, Fox is in it for its future.

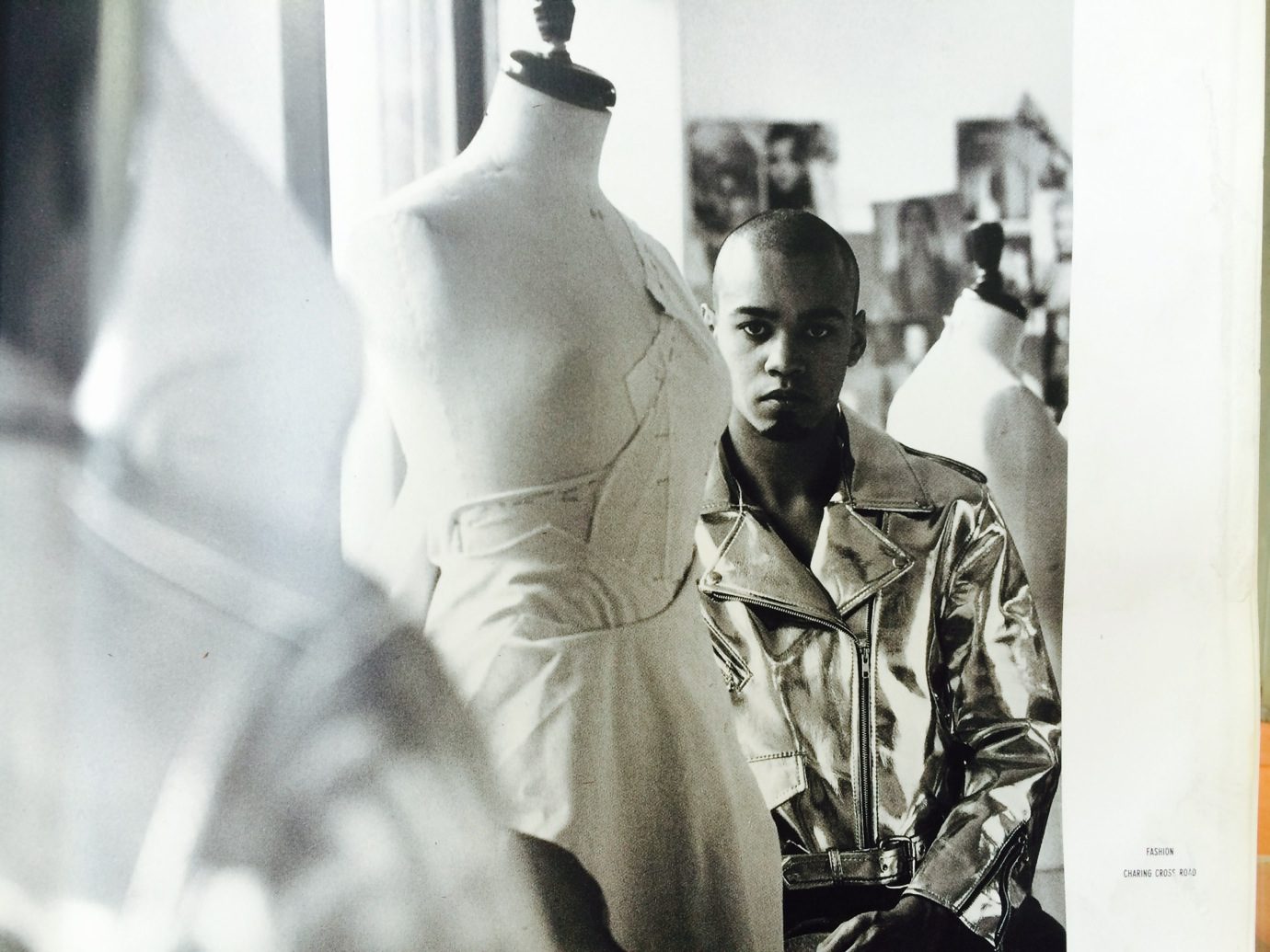

What excites Fox is a good story. Her greatest works—from the scorched felt pieces of her MA Fashion collection from Central Saint Martins in 1996, to her “Fashion and Modernity” project with fashion theorist Caroline Evans in 2004, and up to her run now as the director of Parsons’ Fashion Design and Society MFA program—are so closely concerned with fashion narrative that her work has become an archetype for the stories they tell. As a designer and research fellow, she explored fashion’s intrinsic links to smell, sound and memory through innovative textile design and collaborative installations. As an MFA director, it makes perfect sense that she encourages her students to follow a similar multisensory combination that includes, but is by no means limited to art, film, photography and runway. “There’s something interesting about fashion, when you let go of it and it becomes public property,” she muses. Fox isn’t afraid of the lack of preciousness in fashion; she enjoys it. “Let other people in,” she continues. “Let them engage.”

Easily distinguishable by her bowl haircut, she lists the achievements of her graduate students in a tactful, quietly determined voice. The fashion world is taking stock of New York’s design talents. The first person they’re ringing is Fox. “Before I left for China, I had a creative director from Donna Karan in my office and then I had Nike, ” says Fox. And with her Hackney flat sold (“I bought it when nobody would go there because it was too dangerous.”), Fox isn’t hard-pressed to change her calling card soon. After all, her work has only just begun.

“I didn’t come to New York to deliver a US education.”

SOPHIA GONZALEZ: What’s curious is that although Parsons has taught Donna Karan, Alexander Wang and Marc Jacobs, the MFA program is still so new.

SHELLY FOX: The reason why the MFA is important in New York is because they don’t have anything similar. Graduate programs are really quite rare in America for fashion, especially when you compare it to a country like the UK, that has more.

How is this MFA different from these other programs?

When I came over in January 2008 as a Donna Karan professor, the program didn’t exist. I was able to start from scratch. The MFA stands alone because we are highly critical. We get the students to be self-critical. And what’s important, what I built into the program was fashion presentation. And so, there are courses that deal with photography, filmmaking, curating.

It almost sounds like you’ve tackled areas of what students are missing out on when they graduate at the BA level.

“When you’re being constructively critical of students’ work, they realize it’s valuable. I think that when they realize it’s valuable, it lives on.”

It’s not enough to just be a designer anymore. The students have to be aware of where they position themselves—not just in the market but also in the world.

I saw this with Louise [Wilson] at Saint Martins. She really drove in the need for designers to develop their own fashion identity. You also studied there.

Yes, I graduated from the MA in 1996 and set up my label immediately. Liberty bought my collection, so I was doing that for eight years. While I was doing that, I was exhibiting internationally and teaching on and off.

Did you see a change, in coming over from the UK? It’s an entirely different experience to study and teach in America.

It is.

I know that I felt a shock when I went to Saint Martins to do the MA in journalism. American universities tend do a lot of handholding.

I think you hit the nail on the head. But I really enjoyed my MA at Saint Martins. Some people endure it; I enjoyed it. I learned a lot from Louise [Wilson] and I think that when I came here, I didn’t come to New York to deliver a US education.

How’s that?

My students are really international. I’ve had everyone from a 22 to a 32-year-old student and everything in between. In my first year, I only had one American and she came from architecture—not fashion. I’ve had students coming out of BFA programs who are really independent and hardworking. And then I’ve had 28-year-old students who are a pain in the ass. They’ve come right out of the industry and they’re struggling and insecure. But actually when they get used to it, they’re really strong.

[Laughs] When I started the MA, I was 27 and five years older than everyone. Maybe that had something to do with it.

And the level of criticism. Actually, you can tell it upsets all of them in the beginning. But you know that they’re grateful for it. When you’re being constructively critical of their work, they realize it’s valuable. I think that when they realize it’s valuable, it lives on.

“If you haven’t got a great idea in the beginning, you haven’t got an idea.”

Where has everyone gone off to?

I’ve had students go to Donna Karan, Burberry; so many places. Two or three of them have set up their own businesses. One of them [Melitta Baumeister] is selling at Dover Street Market in New York, London and now Tokyo. She’s been commissioned by Adrian Joffe to do sculptures for Comme des Garçons.

Sounds highly conceptual. New York has always had this reputation for being the commercial fashion capital. Sometimes I wonder if it’s possible to be both.

I think that there could be a balance. If you haven’t got a great idea in the beginning, you haven’t got an idea.

What about the importance of practice-based research?

I had always assumed that if you’re a designer, you’re there as a practitioner and you research. But we have an industry that just downloads style.com all day and regurgitates it out, so maybe it’s not usual.

Research should always be an element of the work. I also think that, delving even further, for a designer to reflect on the importance and value of his work and ideas—this is not always done.

You’re right. It’s not. When we look at the fashion industry at the moment, it’s a lot of mediocrity.

Hmm…do you see a shift in the industry?

Yeah, I see huge shifts. I think that these cities need to stop labelling themselves in this broad-sweeping way, because there is a lot of creativity in New York. I think that’s why my students are standing out—New York needs them.

I know that for me, I went to study at Saint Martins because there was nothing for me here in fashion journalism.

I mean, they really need to work on this. Whether it’s fashion curating or journalism, there’s a whole array of things that could be done.

“If you start out with a project and you know what you want to design, then why are you bothering?”

GONZALEZ: Do you think the attitude is changing and people are starting to recognize the need for fashion in higher education?

It is. And we’ve had a lot of industry support. I think New York is a very can-do, will-do city. It’s refreshing when you’re dealing with money. Americans are not shy about talking about money. I’d go into a meeting and they’d ask me, “How much do you want?” And then they’d sign a check. And I’d say, “Oh my gosh…uh, thank you.” Diane von Furstenberg gave us an enormous gift: $250,000 in scholarships. Simon Collins, who was the dean, has been really great in bringing in those sponsorships. He brought in Milk Studios, Gucci, and Kering as sponsors. Others help us out by giving donations or fabrics.

Bringing up the topic of fabrics—I’m not sure if you continue to work on textiles on your own. Do you have the time?

No, I haven’t.

Because when I think of your discoveries, like the “scorched felt” from your graduate body of work, these came along by accident. It’s one thing to say, “You should experiment,” and have an end goal. But have you talked about how important it is to look at so-called “failures”, and to not pass those off because it could lead to something bigger?

Yes, this is something that we talk about with the students. If you start out with a project and you know what you want to design, then why are you bothering? Why are you here? Because what you’re missing out on is the process of design and all the possibilities to come from that process, which will lead you to other projects later on. You’re not going to be a good designer if you’re not allowing yourself to be open. So we really encourage them to make mistakes and to fail, although it’s not really a failure.

Right, because there’s no right or wrong.

Exactly. When the students ask, “Is this working?” I say, “I don’t know. Is it?”

“If your garments don’t stand out without the story behind it, then you’re wasting your time.”

Even at the MA level, when I was in studio, there were some collections I personally didn’t get. A tutor on the course might not like it, but Louise [Wilson] loved it. Do you know what I mean? How do you weigh a successful body of work?

When you’re working with students, you’re trying to equip them with the skills to develop their ideas so they start to recognize an idea instinctively—even if they can’t articulate it. We push them to think about their research and where it might lead. The research might purely be “hand cutting”. That’s their interest, that’s their obsession. It could be hand cutting and nothing more, but there will be things that feed that. I’ll give you an example: I had a student who was actually an American from Boston, but lived in Pakistan. He did his whole collection [centred] around a prisoner—His research was real, on the ground. He met the prisoner’s family. Then there was another student. Hers was about the sterilization of women in Peru with writing on the clothes. These were highly political collections, but I did say to them, “If your garments don’t stand out without the story behind it, then you’re wasting your time.”

It reminds me of the book “The Painted Word” by Tom Wolfe. Have you read it? The book argued that in order to appreciate modern art, you had to understand the literal concept behind it. Do you think you have to have an understanding of the designer’s vision to appreciate a body of work? Or should you just be able to look at it and say, “Oh, wow”?

People don’t need to know the story. There’s this criticism that fashion designers, or designers like myself, over-conceptualize their work. I don’t think I ever did. I think other people did that for me.

“I think that way too many people show in New York who do not need to show.”

Part of your own background has been to approach fashion as a multisensory experience. Whether it was through smell or memory, fashion can be experienced without wearing it.

I remember the first exhibition I curated with my work. I suddenly realized that I had to think of the person from the minute they walked in to the minute they walked around the space and how they would feel. It’s actually really hard. With fashion shows, the whole experience has to do with the music, hair, makeup and models, with everything. Personally, I think that way too many people show in New York who do not need to show. I don’t know how you do your jobs. There needs to be a massive edit.

And now, designers will organize the order of their runway looks based on how the collection will appear online.

It’s consumed digitally and people only see the front. That’s why the photography and film that we do in the program is really strong. And the reason for it is because of an experience of mine. My [runway] show got cancelled in Paris. I was already working with SHOWstudio. This was in 2002 and they were going to live stream the show, which was a big deal because nobody was doing it. When the [runway] show got cancelled, Nick Knight and Penny Martin—that team, they were really supportive. So they were like, “Okay, we’re going to do something different.” So we hired still photographers and created a film that we launched at the ICA in London. The time I spent working with SHOWstudio and Penny’s team was so creative. I suddenly realized that it’s not all about runway. Not everyone can do runway. It’s a digital world. The students have to think in a different way. We all have to think in a different way.