How did you get into fashion?

I was studying architecture, but I quickly realized that I wasn’t interested at all. I always saw these really cool people in the halls of residence in the East End, where I lived, so I followed them, and turned out they went to fashion school. They looked like me, the architects didn’t look like me. So, I transferred to the fashion programme. I really wanted to go to CSM, but I was so scared of it, I knew the history, and I thought I would never be good enough.

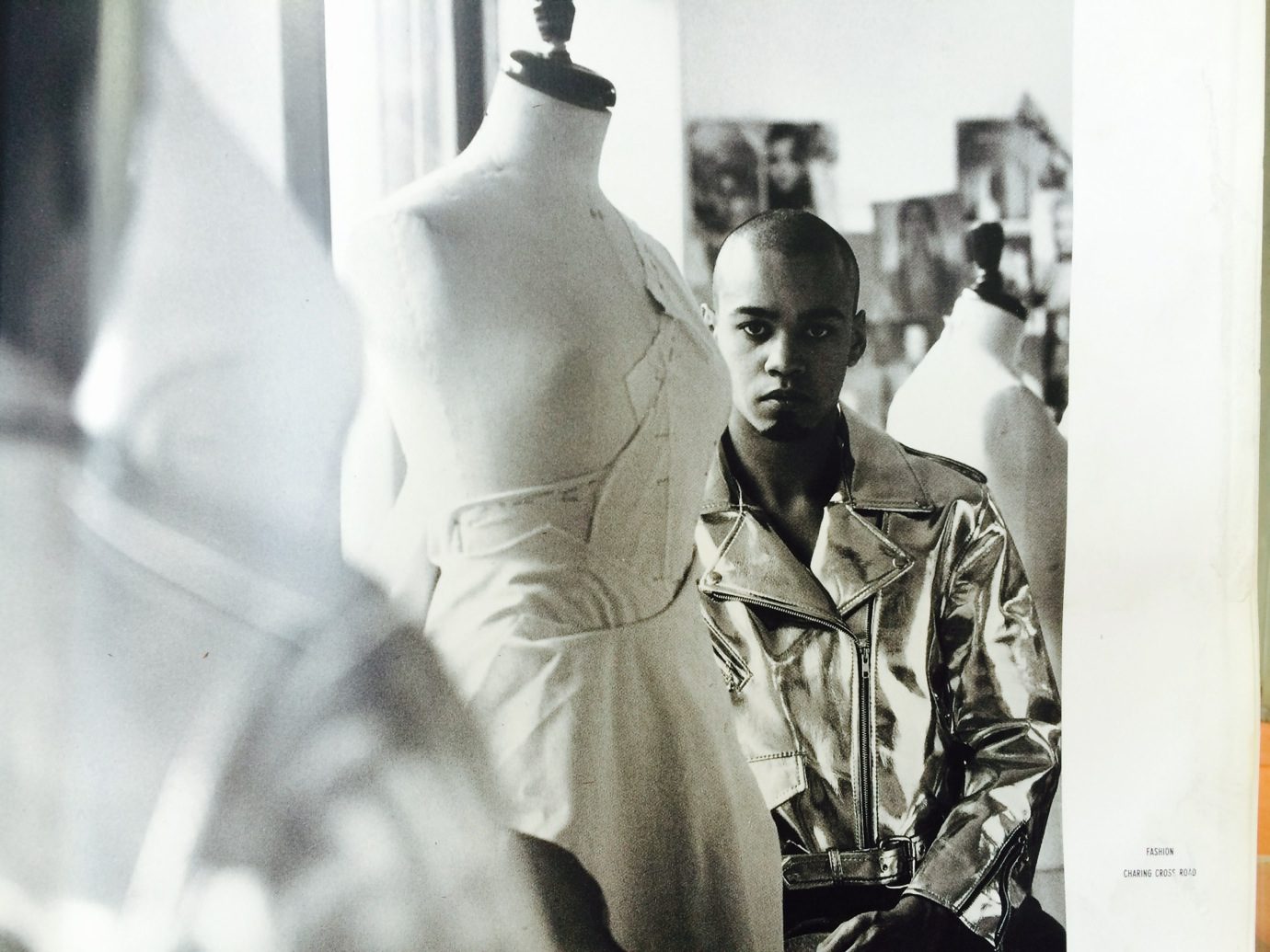

Before I enrolled at CSM, I was already working and doing textiles for different companies, so I asked whether I could defer for a year to gain more experience first. It was the best decision I ever made because the first person I met was this very young, East End boy named Lee McQueen. We hit it off straight away, and I mean really hit it off. I would do prints and fabrics that he would design with and we would do projects together. We loved the same clubs, we loved the same music, we loved the same boys. We laughed constantly. Of course, I had amazing teachers, but the most amazing thing about CSM were all the people that would come in and the people that you were surrounded with.

“OF COURSE, I HAD AMAZING TEACHERS, BUT THE MOST AMAZING THING ABOUT CSM WERE THE PEOPLE THAT YOU WERE SURROUNDED WITH.”

After graduation, I went back into freelance forecasting, Lee moved into my house in South London in Tooting and we started McQueen. It was not really conscious. Isabella Blow would want something, so we would dye some fabric and make a dress. Richard Burbridge, the photographer, was getting married so we made his fiancé a dress.

We did that first collection, Taxi Driver, in our kitchen. I took the kitchen door off its hinges and made a print table. We borrowed material from CSM. We always thought Louise didn’t know, but a few years later she said to me, “It’s time you bring that back.”

It was never a goal of mine to become a teacher, but when I was invited as a technician at CSM, I really needed the facilities. In 1996, Bobby Hillson was consulting and recruiting for San Francisco, and she asked me about it, so I thought, “Yeah, I’ll go for three months.”

We started to work with the students and I saw the response really quickly. They were exactly the same as the students at CSM but they just needed the right guidance. By the time September came around, I couldn’t leave these young people. It just carried on like that to the point where I completely fell in love with Northern California. There’s such a depth to San Francisco, the history of it, the music, the singing, the forward-thinking on environmental issues.

I really wanted to learn what that term “lifestyle” was. Designing for a lifestyle ‒ Gap, Banana Republic, Levi’s, North Face ‒ all these people really knew how to, they created it. Merchandising is an American invention.