“A GARMENT CAN NOT SPEAK NOR CAN IT COMMUNICATE.”

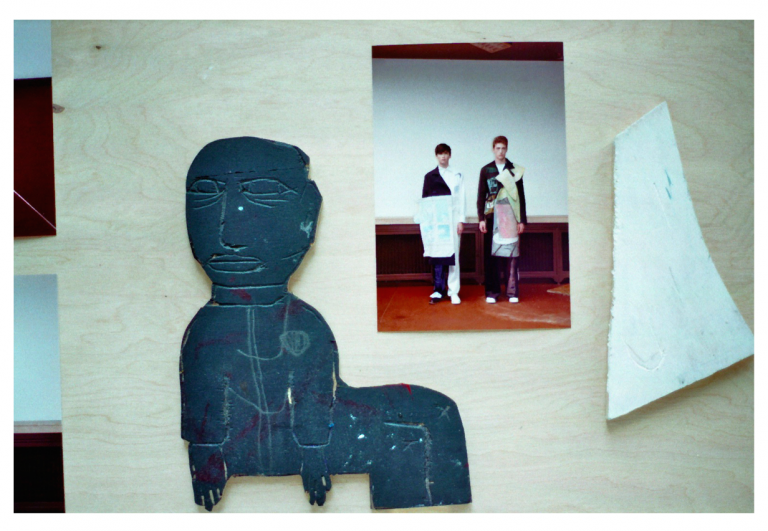

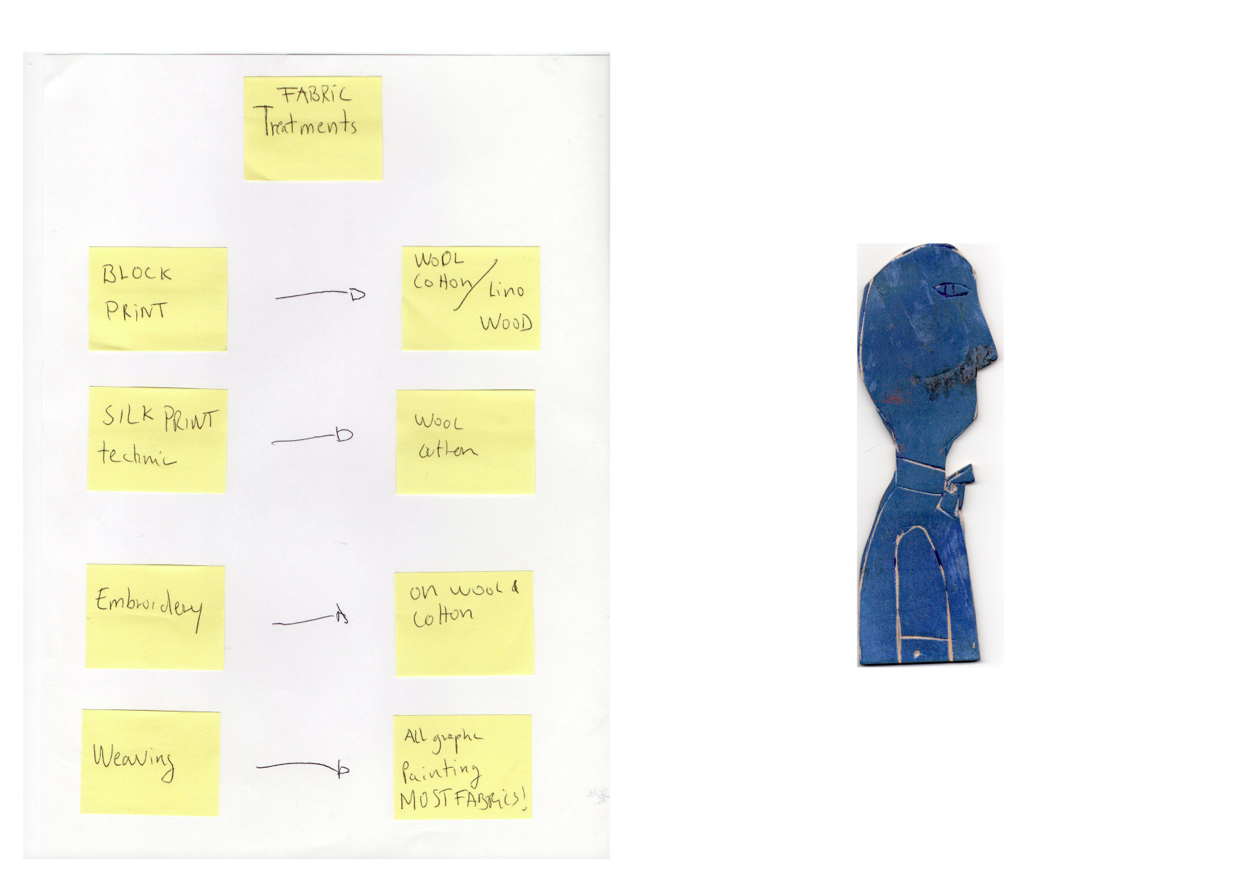

“In the research of all my years at the academy some strong statements came back over and over again. The, apparently, vital element of reference and research — periodic and sociologic,” Peter states. “Is it for this kind of person, is it this kind of garment?” tutors would ask. “The final idea always ended with a romanticisation of what we were doing,” he continues. To test the waters, Peter decided to send a selection of his garments to the people he told it was for. “I gave the garment to some people because some other person said: it is for those people.”

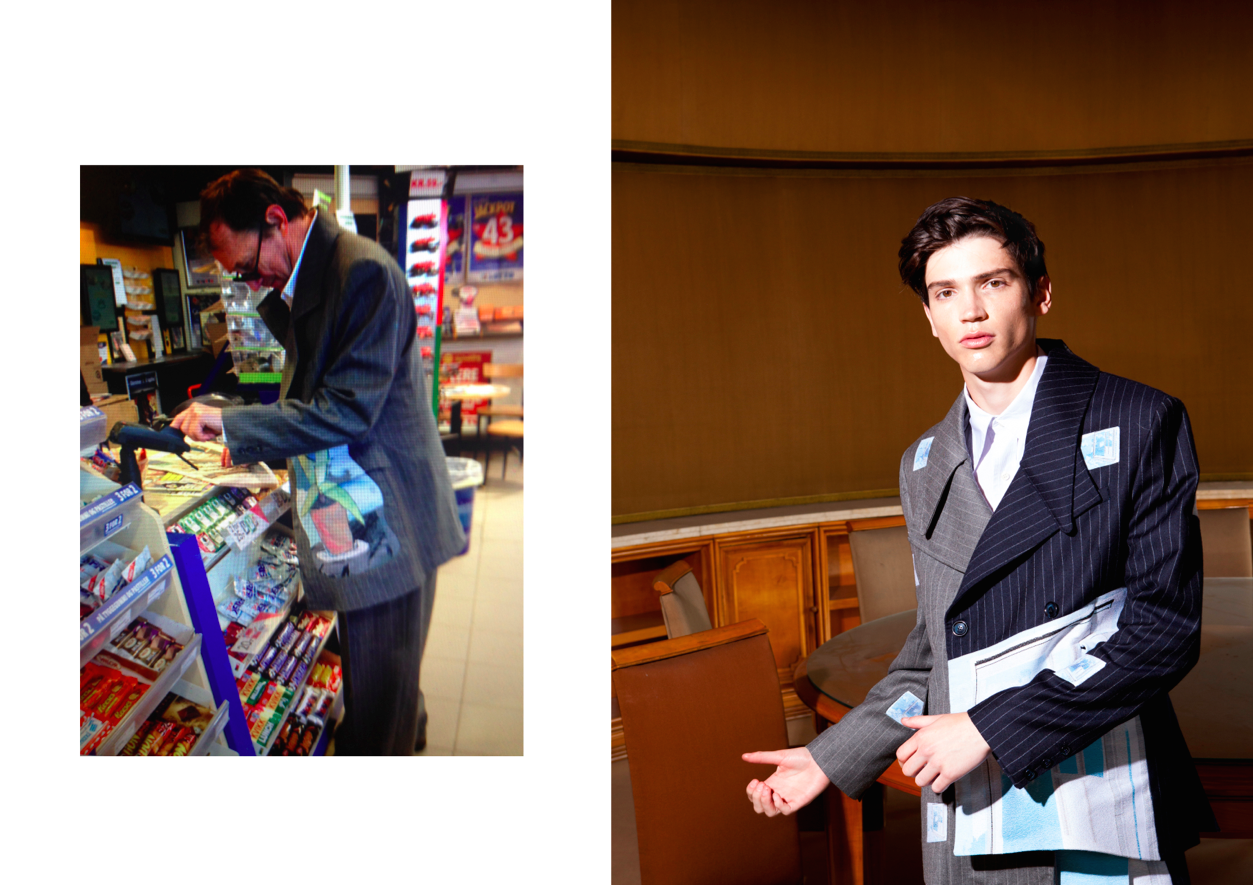

The clothes were sent to fishermen in Dyfjord, Norway. Peter’s request was simple: wear the garment and take a picture of yourself while doing what you would do everyday. He aimed to see if his romantic combination of research images would actually exist in real life — the pictures show his ‘idealised man for whom the clothes are made’ taking the bus, paying for goods in a store, looking at fishing boats, drinking in a cafe.

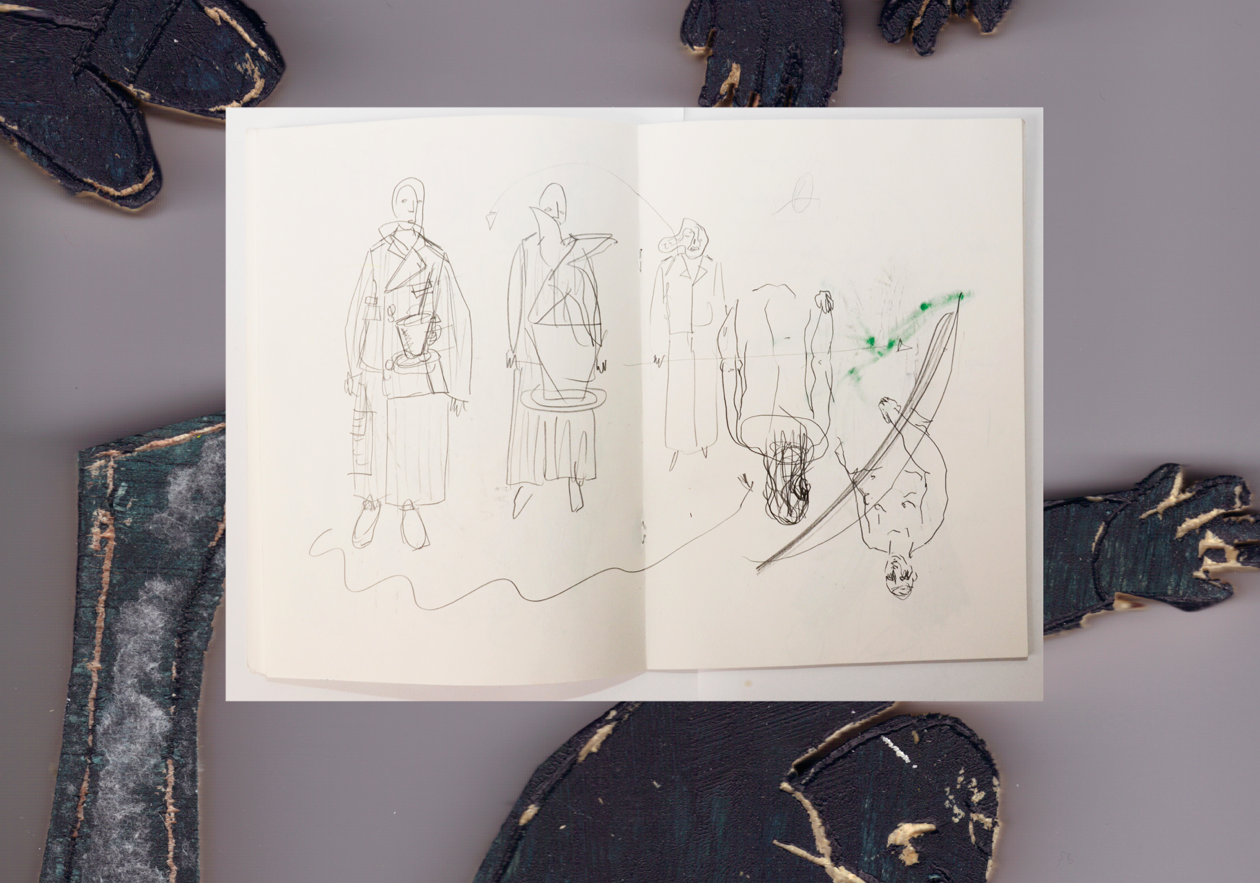

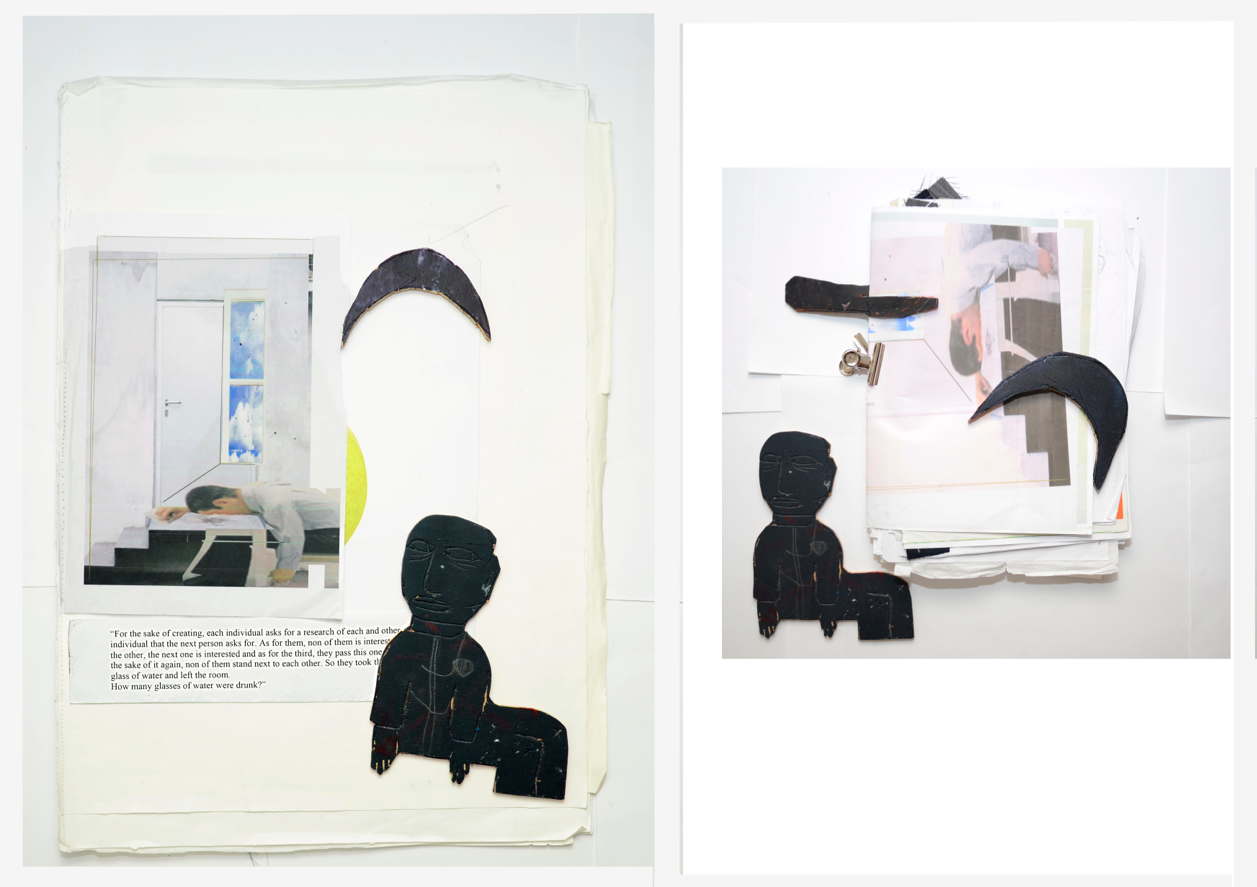

Through receiving pictures of the garments worn in real-life situations, he hopes to devalue the ideas that we put into high-end fashion garments, and give back their actual value. Philosophising on the subject — Schamaun calls himself a mental victim of Kierkegaard’s dizziness of freedom — he came to the following conclusion: “The more you put of vocal words=air, or written words-paper, on object “X”, the more it loses its “real”. The more you point=a finger, on object “X”, the more it loses its real. The object “X” is only at its most real, when only stood there as it “is”. The more of a function, and fit it into something it is no longer, the object’s core.

My goal for this collection, was to take all this away. To stand next to the garments, in the most silent way. To show that a garment can not speak nor can communicate.”