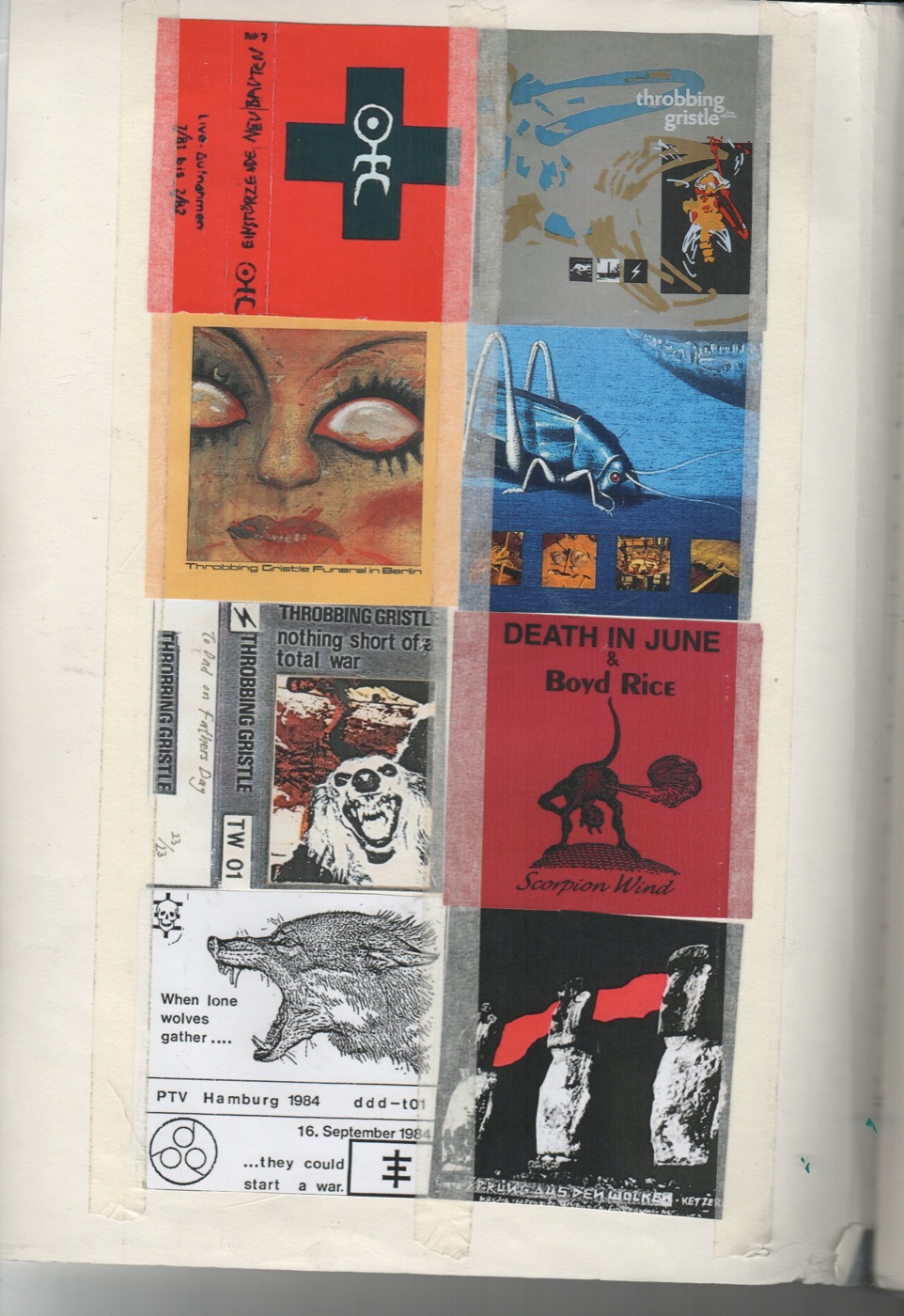

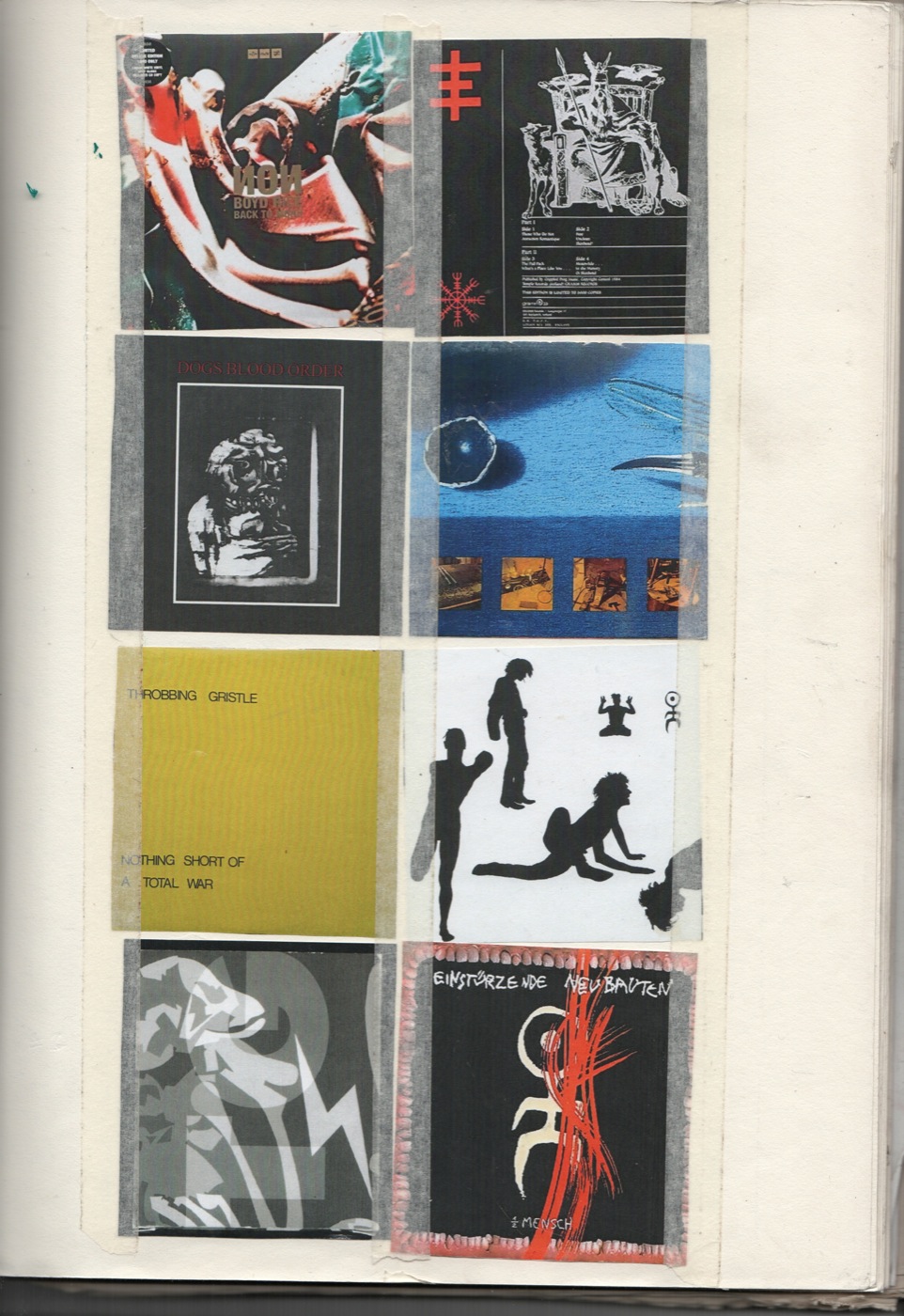

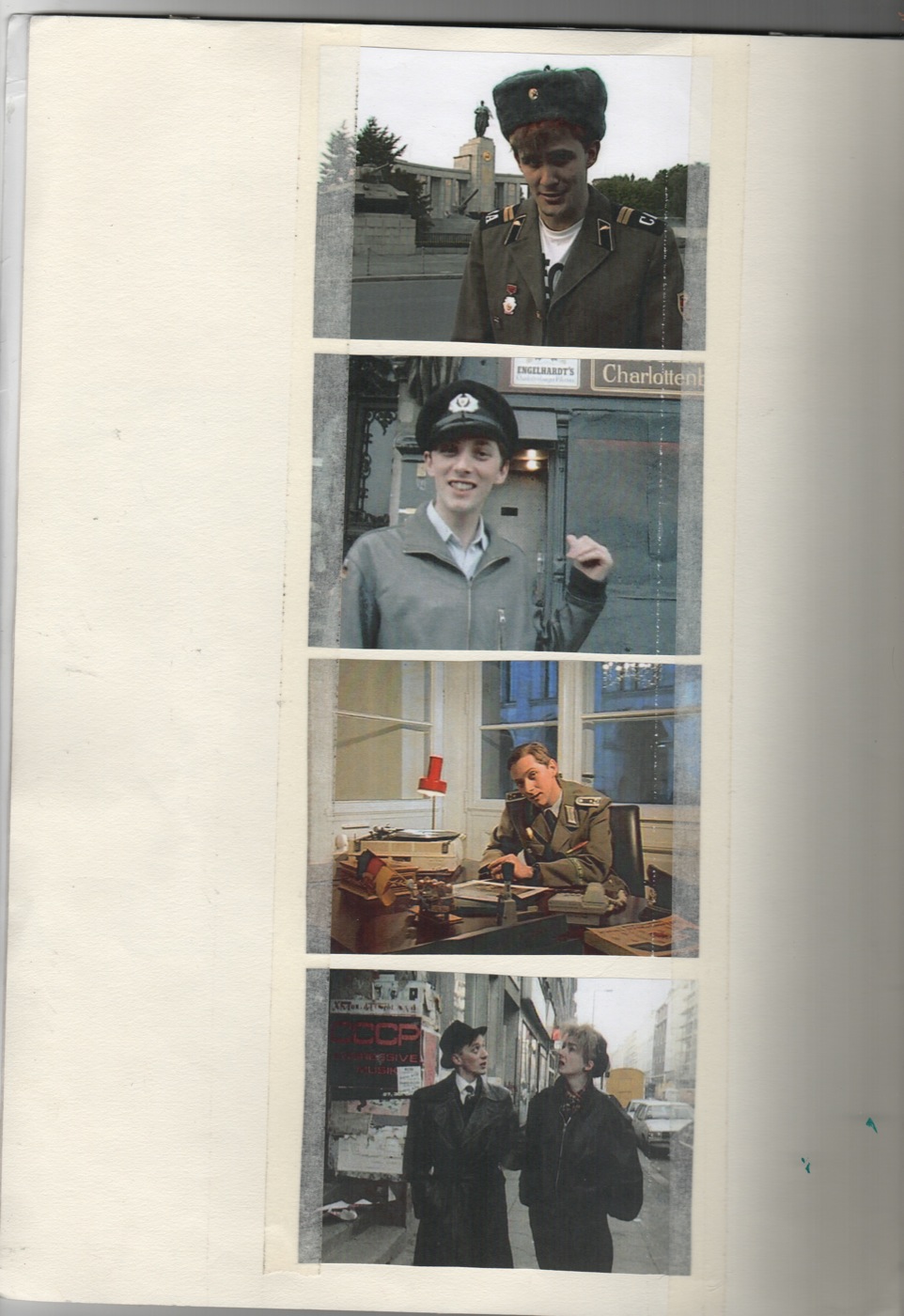

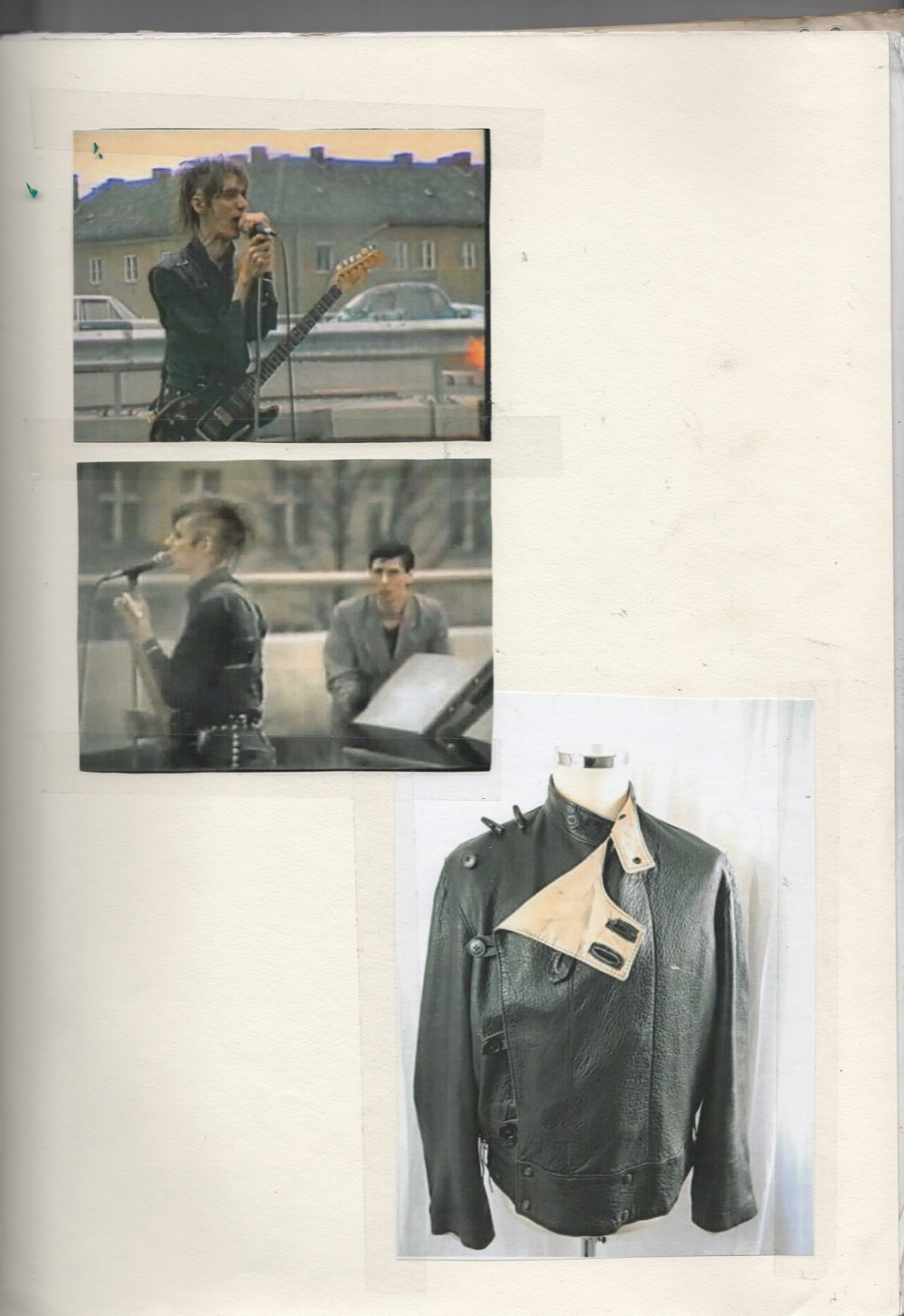

Images of album covers by Throbbing Gristle and Einstürzende Neubauten (whom Viersen has been a fan of since the age of 14), run alongside screen captures from the films of Dario Argento, Roman Polanski, Alain Robbe-Grillet and Mark Reeder’s documentary B-Movie: Lust & Sound in West Berlin, and pervade the pages of his portfolio. “I figured I’d put a little bit of myself in there,” he says with a half-smile.

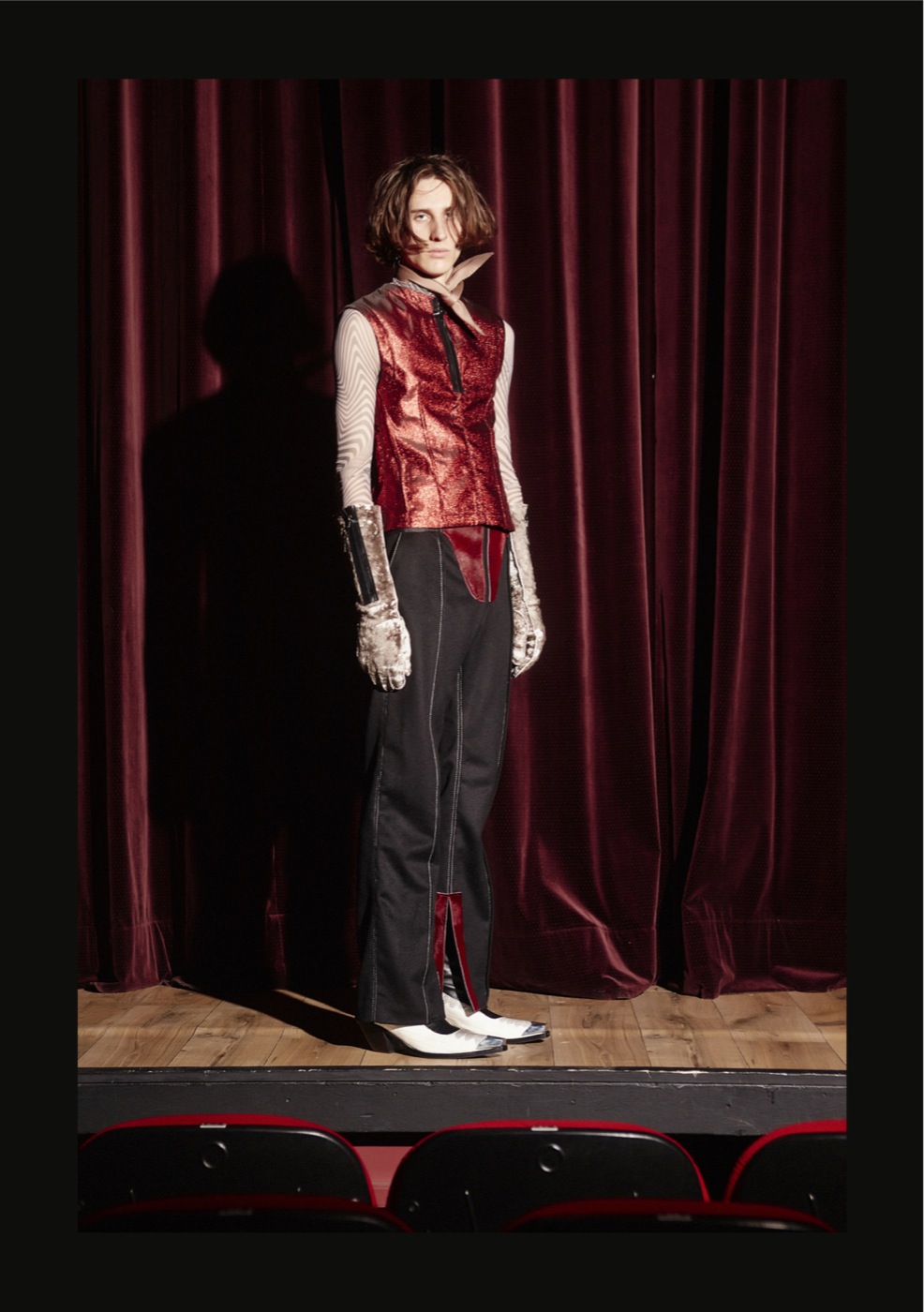

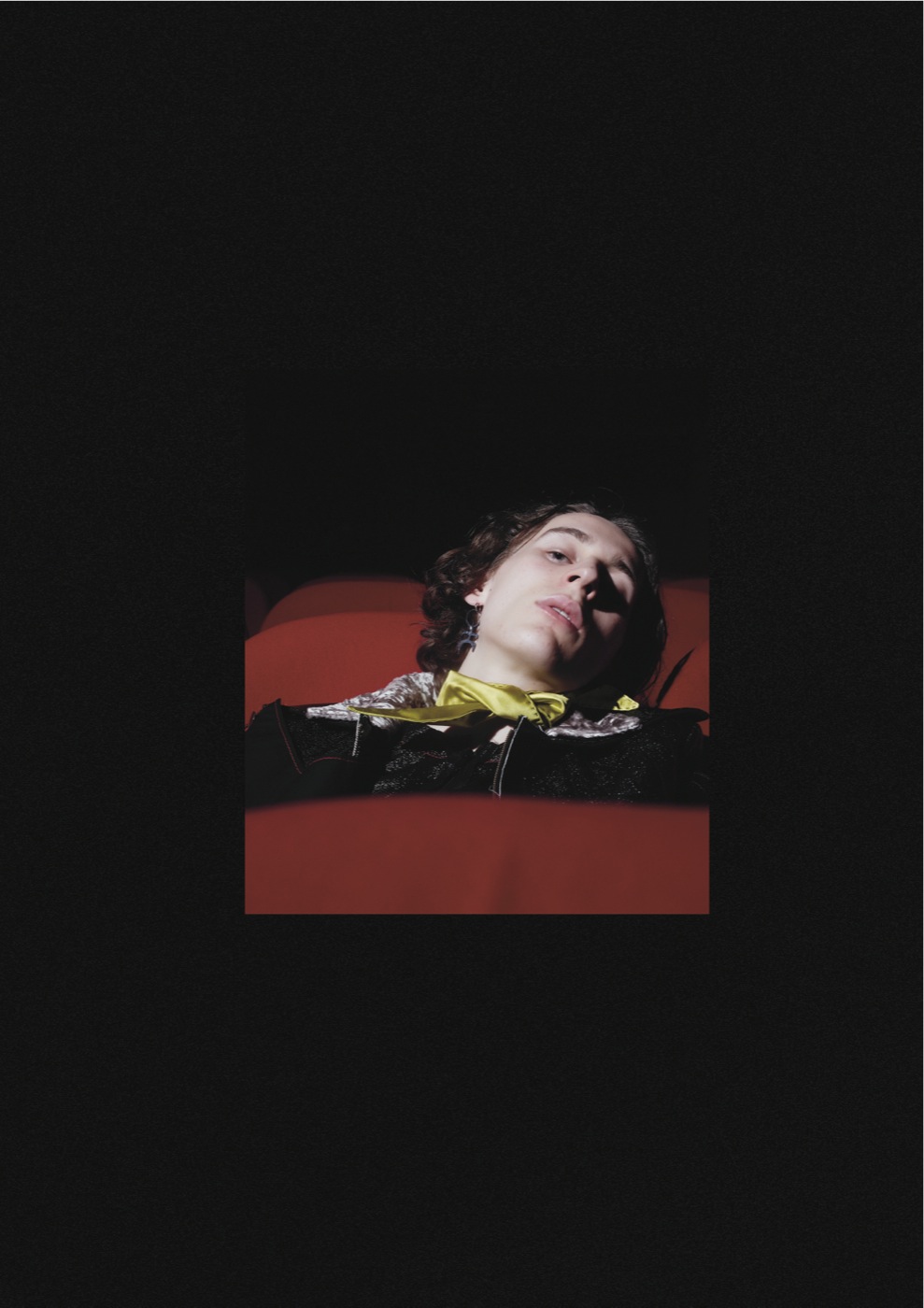

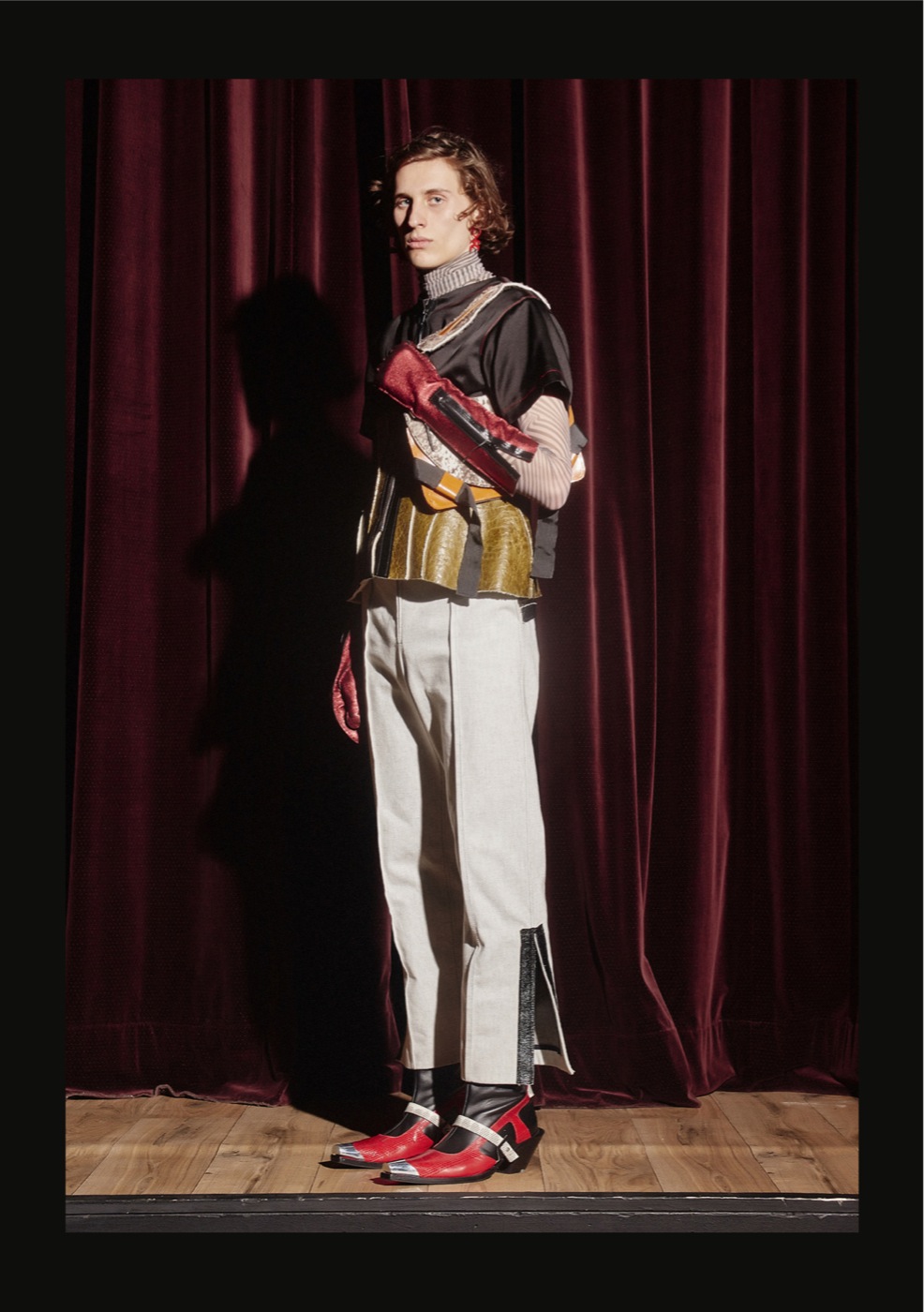

Reeder’s documentary, which was released only last year, showcases archive film footage of the art and music scene in 1980’s West Berlin, starring prominent artists who were active during the time, such as Nick Cave and Blixa Bargeld. Also involved in the scene was German artist Salomé, who alongside Luciano Castelli formed the band Geile Tiere (“Horny Animals”). The photographic self-portraits created by Castelli, as well as the fantastical theatricality of the two artists combined, eventually led to Viersen looking into the practice of cross-dressing. As a happy coincidence, a similar feat was present in Polanski’s The Tenant — a film that had a potent influence on his collection — which sees its main character Trelkovsky (played by Polanski himself) experiment with dressing up as a woman.

Curious to know what the designer’s relationship to drag practice is, he tells me: “I’m not really familiar with the scene, because I have no affiliation with it whatsoever, but I am intrigued by it, that’s for sure. I like the daringness of it.”