“MY TUTOR MARK ARMSTRONG INSPIRED ME TO RESEARCH UNTIL MY EYES WERE SORE.”

The Royal 20: Isabella Macleod

Living in an age of information overload, we are constantly exposed to imagery. In this sense, it can be easy to sometimes become so immersed in the visual splendour of fashion, that we often forget it is a sensory experience most of all. Isabella Macleod helps us remember through her subtle and evocative approach to menswear. Like being let in on a secret, her clothing is about sharing narratives and designing from a personal point of view. We learn more about her practice and opinions on an industry she’s keen to enter.

Is your work a direct extension of your identity?

I find identity a difficult word and I would be very bored if I had to define mine. I have tastes which determine what I’m naturally drawn to; thus informing my design. But I am mostly drawn to characteristics of men, so it’s an extension of what I see in that. My work is always personal, otherwise I become very lazy and disengaged. I only ever use models who I have an emotional relationship with. Having said that, once I was not involved with anyone who wanted to be part of my life openly, so I used myself. It was some of the best work I’d ever produced.

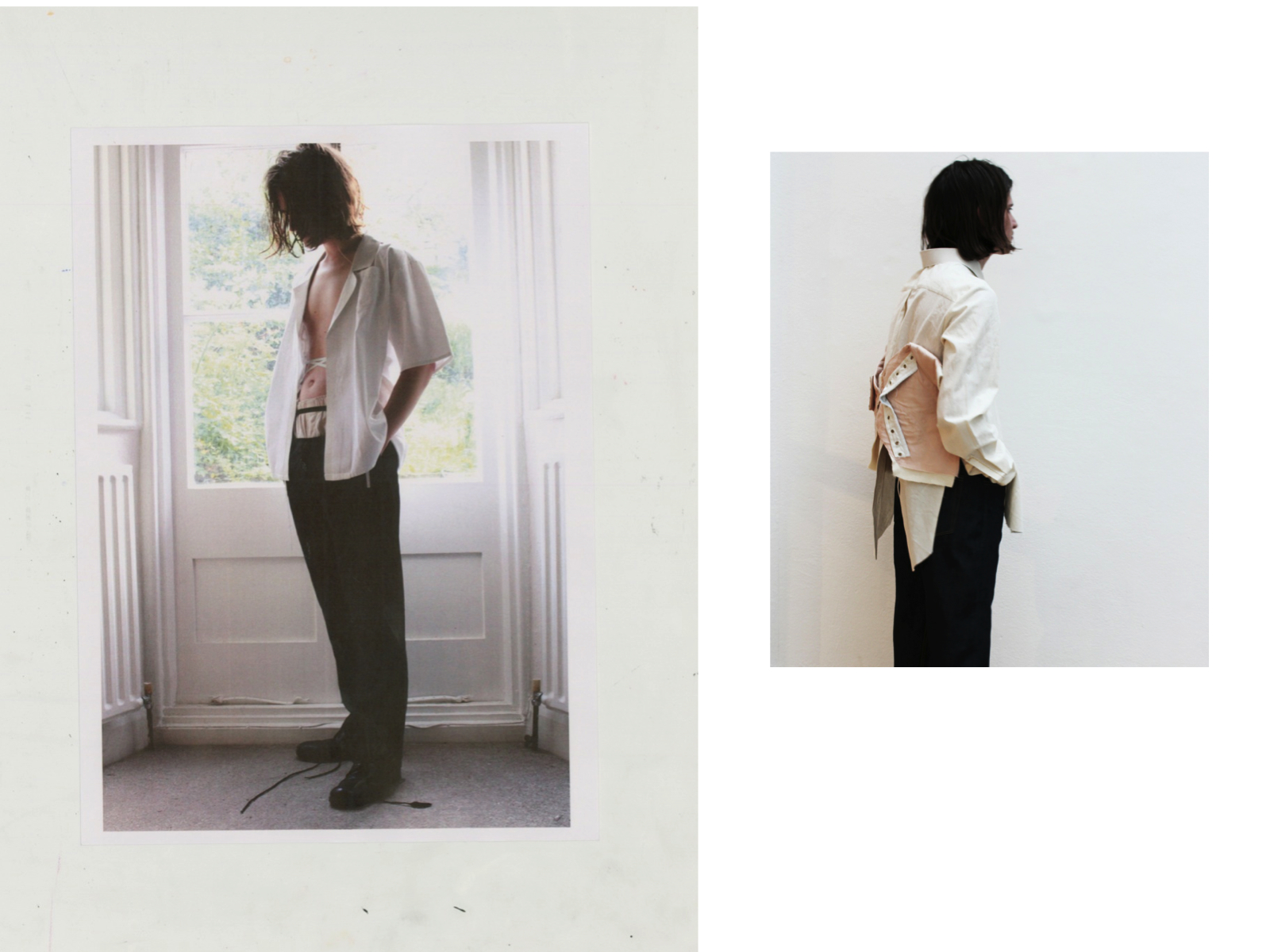

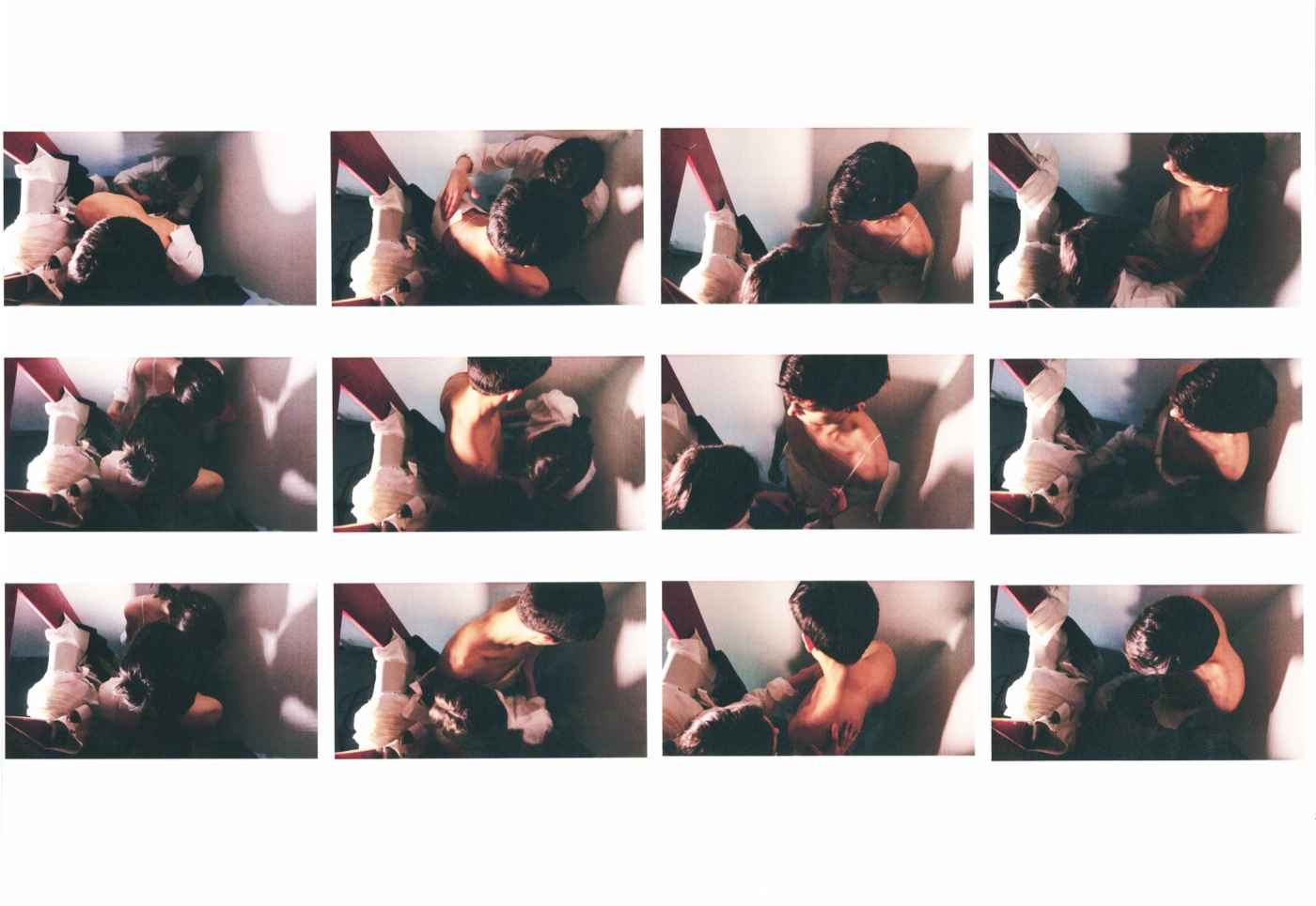

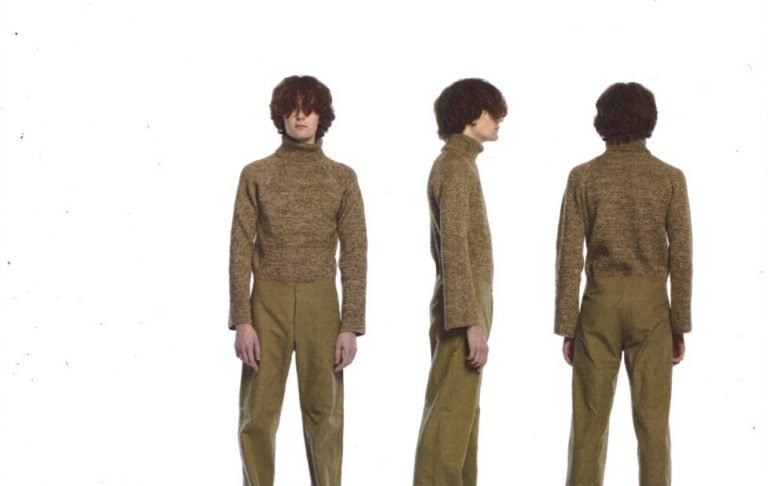

The starting point of this collection is nicely summed up by Merleau-Ponty: “Since the same body sees and touches, visible and tangible belong to the same world.” I wanted to think about the space between our bodies and our clothing. What happens when a man puts on a corset, and when a woman wears a man’s jacket? We are so visually stimulated by these suggestions, that the actual feeling associated with this is swept aside. But if they are concealed, then suddenly the focus is returned to the experience. I tailored the clothes around pieces — such as a pair of trousers around an original corset from the Soviet Union — and left only little glimpses of details to inspire a curiosity and closer investigation.

Tell us about how the RCA has shaped your approach?

The RCA is really great for research because of the people they put into your path. Research became a huge part of my practice after writing my dissertation, ‘Mapping Eroticism’, as my tutor Mark Armstrong inspired me to research until my eyes were sore. Then my second year tutor, Brian Kirkby encouraged me to continue research alongside making: this was the best advice anyone had ever given me!

Concepts in fashion can often mean moodboards or press-releases, which are the most uninspiring, un-researched things ever. That’s not to say they don’t serve a purpose — I am just not sure that fashion and research have totally met in the right place yet. There is so much potential, it is really exciting. The problem for me was getting the right balance and not over-thinking the research. It still has to have the beauty that clothes have, and not become stuck on a page of over-analysed thoughts.

Whilst at the RCA, we had two very different experiences. Our first year was great for teaching us how to be responsible designers. If you suggested a design, then you sure as hell saw it through! It made me so much more rigorous in what I was even thinking of making. It was a sort of mental editing, which I had spent so long doing in physicality prior to the RCA. Our second year subverted this and taught us almost the complete opposite. The idea that you have to make mistakes, as you are making something you actually don’t know how to do — so it is new. Both these approaches gave us an advantage to see that mistakes meant you were doing something new, but you have to be prepared to see it through. The RCA makes you incredibly critical of yourself and at times I was a total mess, but it made me stronger and channelled my creativity into a good place. Everyone comes with stacks of creativity; the RCA is about ensuring you know to keep this controlled, without losing too much of your original energy.

“MY CLOTHES ARE A MEANS TO TELL A NARRATIVE AND THE STORY NEVER ENDS WHEN THE GARMENT IS FINISHED — THAT IS JUST WHEN IT BEGINS.”

Do you understand your work as design or as art?

When it comes to the difference between art and design, design serves a practical purpose. I believe the clothes I make should fit well and comfortably, unless deliberately conceived otherwise. The art part comes later, when you start to document this relationship between body and wearer, and then present it to an audience. My clothes are a means to tell a narrative and the story never ends when the garment is finished — that is just when it begins.

The imagery evoked in fashion is often incredibly powerful, and because clothing is a universal need, fashion can reach a wider audience. I think that we need to stop labelling creative work and placing it within disciplines. Even the term fashion becomes pretty obsolete when you’re trying to create something new. If you see or wear something which makes you feel more than you felt before, then it is something associated with emotion as opposed to an academic term. Design is the act and the finished product becomes its own entity: it has personality and it exists within its own right.

“I WANT TO KNOW WHAT HAPPENS TO MY GARMENTS WHEN THEY’RE WORN BECAUSE I HAVE A RESPONSIBILITY TO THEIR CREATION.”

Are you excited to head out into industry after being in education?

I am really excited to get a real understanding of the industry, having only previously gaining experience in a couple of small, commercial companies. I’m glad that I have had this time to work within my own realm of experiences and immerse myself in conceptual design. But it is easy to form your own opinions of the industry whilst still in education, and it’s important to head out and actually experience how it works.

I’m also interested to see the effect of the industry on my own aesthetic and work ethic. It is great that education gives you the space and freedom to really think about your work, but it will be interesting to see what happens when you have to answer to lots of other people’s time constraints and demands. With that in mind, I am going to do an internship in Paris at Cerruti, and I will continue to make my own garments, books and films.

It’s important for me to continue to produce my own work whilst gaining this industry experience, because the whole point of personal, experimental design is to make mistakes and learn. Equally thinking about trying to deal with the financial side of a brand means you get sucked into a world where you so easily lose sight of your original vision.

I do not also believe what I produce should be deemed ‘successful’ by its cost, or profit margin, for me that is so un-relatable. I would love to produce garments for people and work alongside them, so that I knew I had made something which someone would keep, and that opened a discussion that I also could be a part of. Often brands seem so vulnerable to vacuous criticism and compliments, and the discussion is always way too removed from the designer. I want to know what happens to my garments when they’re worn because I have a responsibility to their creation. I also think working for somebody else always puts things in perspective. I had a job throughout my MA, and although it was not related to clothing, it was the best thing I did for my sanity.