Having been mentored by Alan Norris during her BA at University of Creative Arts Rochester — the head of Hardy Amies and tailor to the Queen — Jess developed a strong set of tailoring skills. Her conceptual framework gained force while assisting Iris van Herpen leading up to her couture show, which came to fruition in the MA collection she presented last month. We spoke with Jess to discover what really makes her tick.

The Royal 20: Jess McGrady

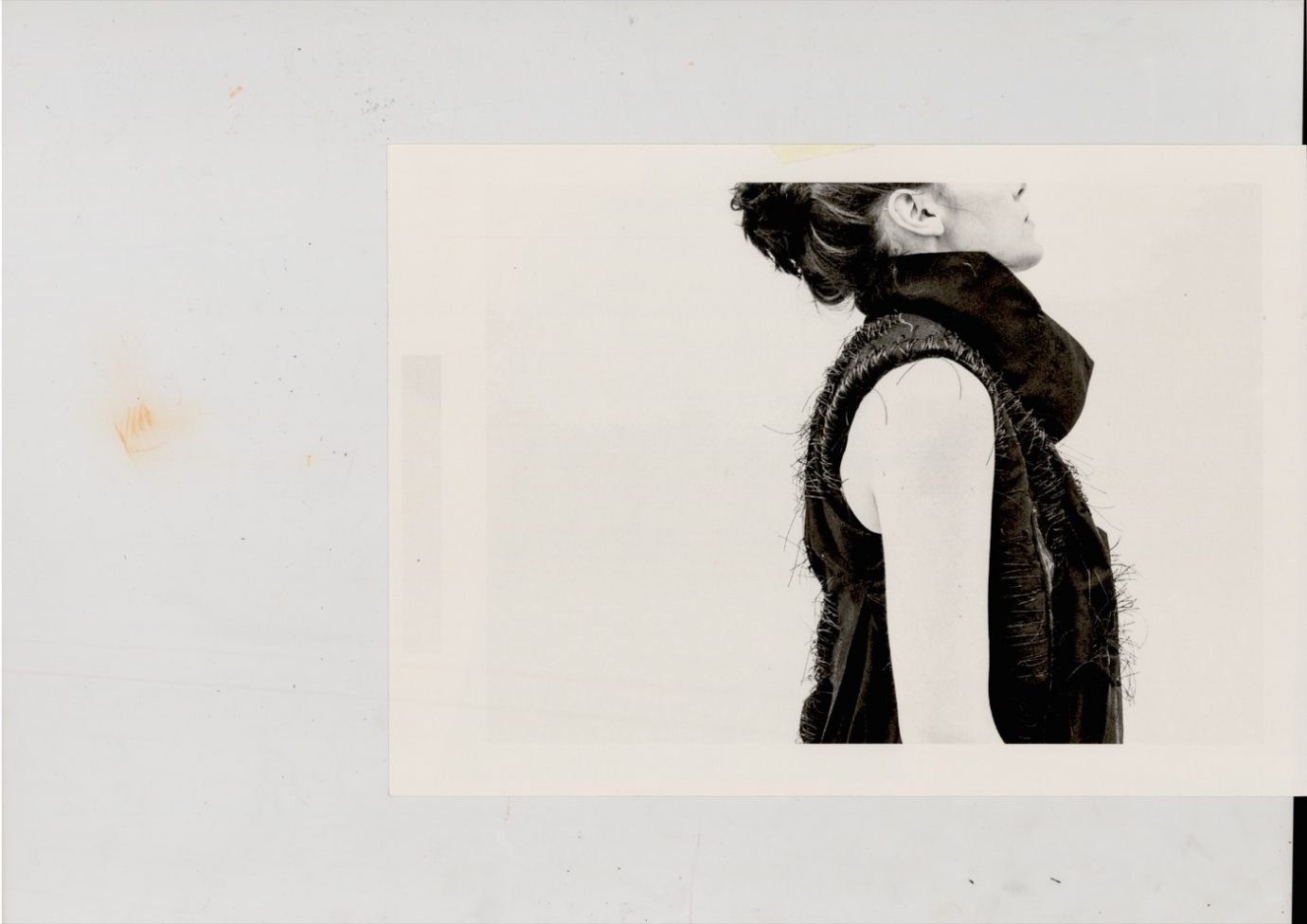

Describing her work as ‘accepting of wearing me’ and ‘pack mentality of I’, Jess McGrady’s focus as a creator is fundamentally centred around the exploration of the self; giving rise to languages not yet pronounced in the current fashion landscape. The Royal College of Art MA Fashion Womenswear graduate often feels a relentless need to investigate alternatives in design: how to create clothing that’s everything one does not expect it to be? How to remove oneself from preconceived notions and add new commentaries and ways of seeing to the general discourse?

“THE CREATION OF SPACES, INSTALLATIONS AND PERFORMANCES ENABLED ME TO TRANSPOSE MYSELF INTO A SPHERE WHERE I COULD REMOVE THE FAMILIARITY OF MY OWN PRECONCEIVED NOTIONS OF CLOTHES, AND HOW WE DRESS AS WOMEN.”

Do you consider your work an extension of your own identity?

My work is very influenced by my upbringing in South London, where cultural belonging and communicating through the clothes one wears is quite present. I would say that my work is indeed about identity and personal growth — when you spend an intense period working on a collection, it is hard not to push personality into the research and construction of a garment. My moves and mannerisms reflect how I would wear the piece. It is important that I frequently wear the clothes I make, especially in the toiling stage, because the garment needs to sit and move in the correct way. It’s like having to constantly refocus in a mirror, creating mini versions of myself through clothing.

How was your experience of the design approach at the RCA?

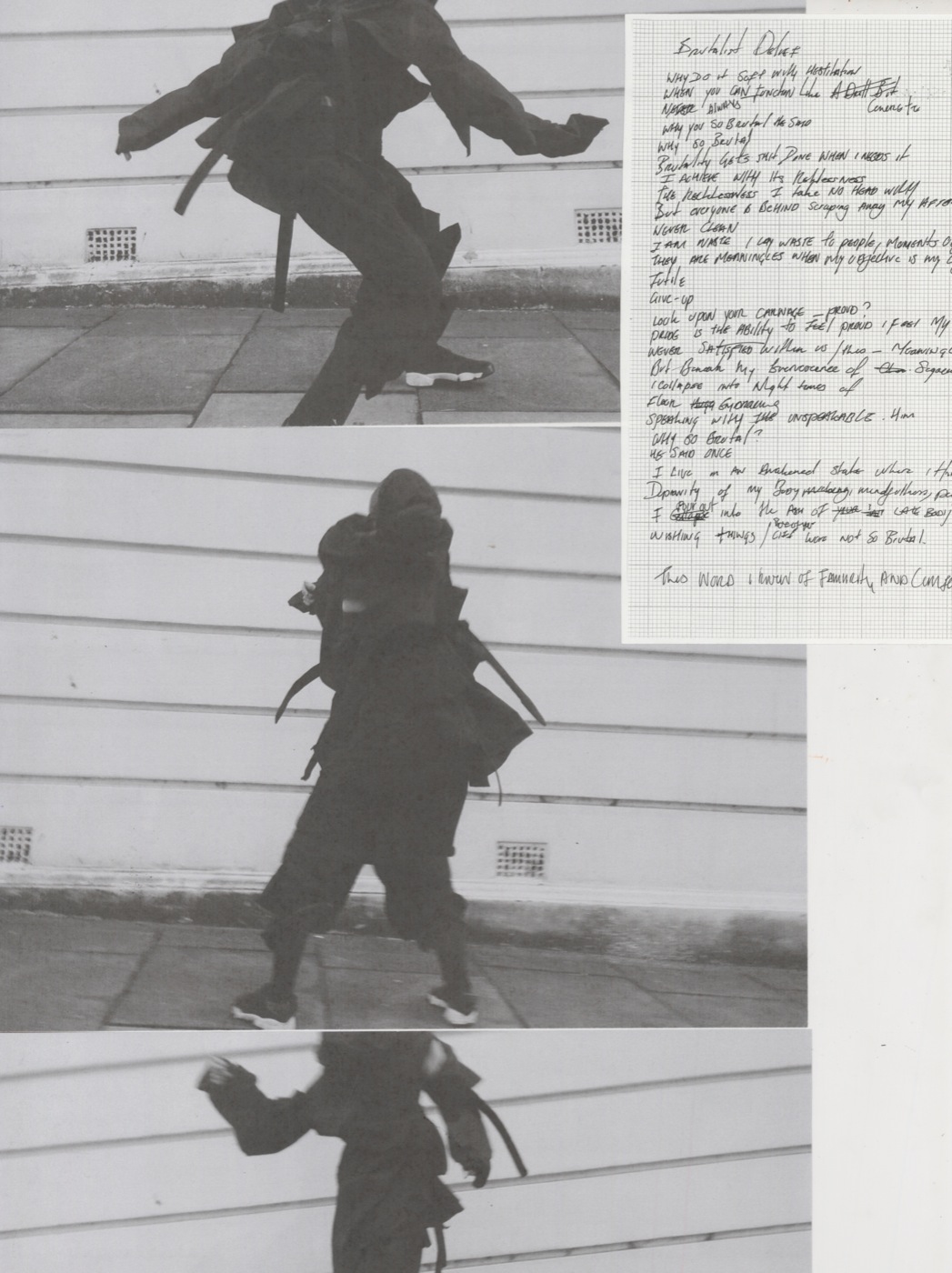

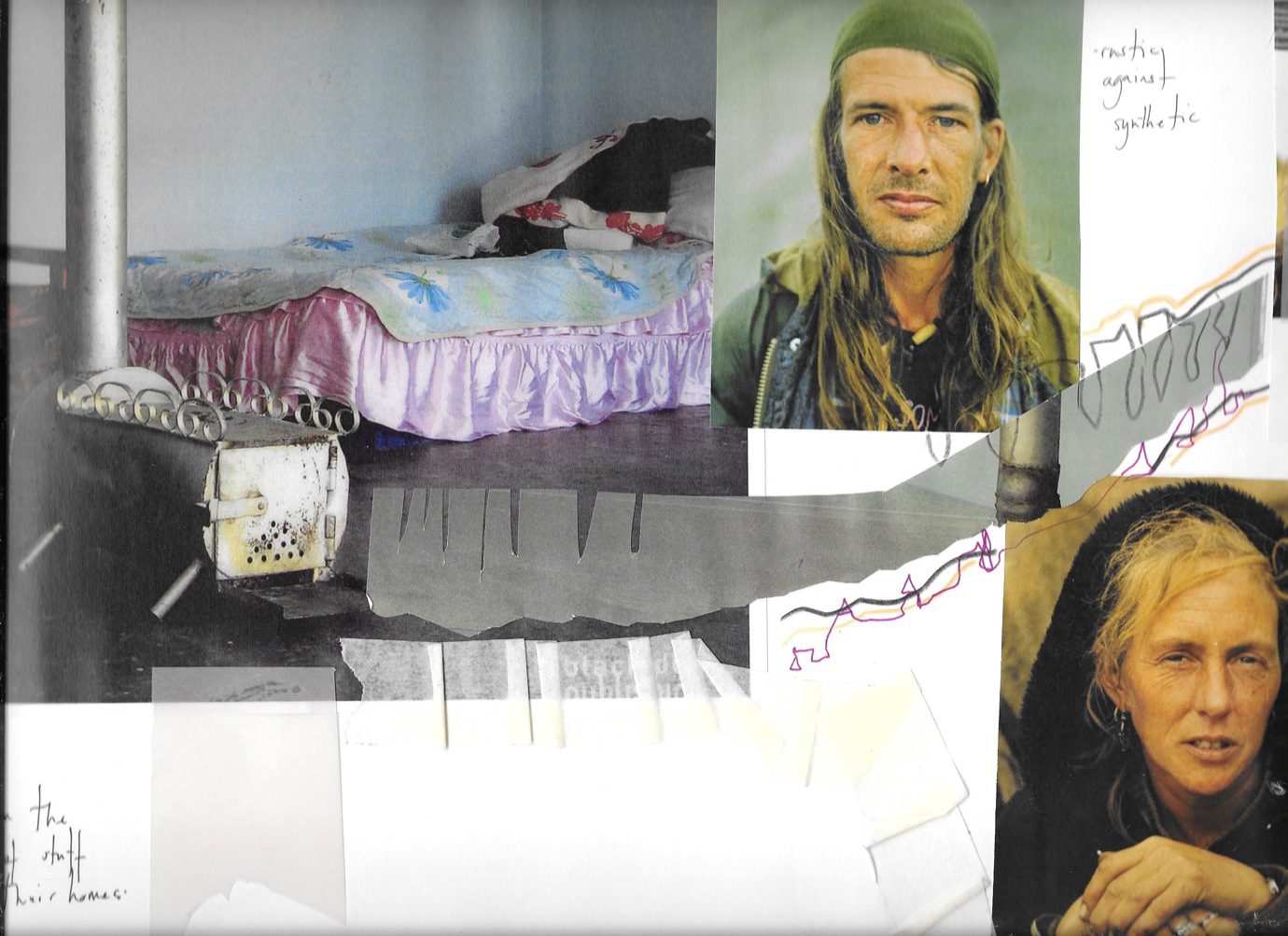

In the beginning I really tried to remove myself from the making, and instead really appreciated the conceptual process, because nowadays we don’t hold on to it as much. The creation of spaces, installations and performances enabled me to transpose myself into a sphere where I could remove the familiarity of my own preconceived notions of clothes, and how we dress as women. What this allowed me to do was to not reference anything from the outside, and I was able to solely reflect on what I was desperately trying to convey in clothing.

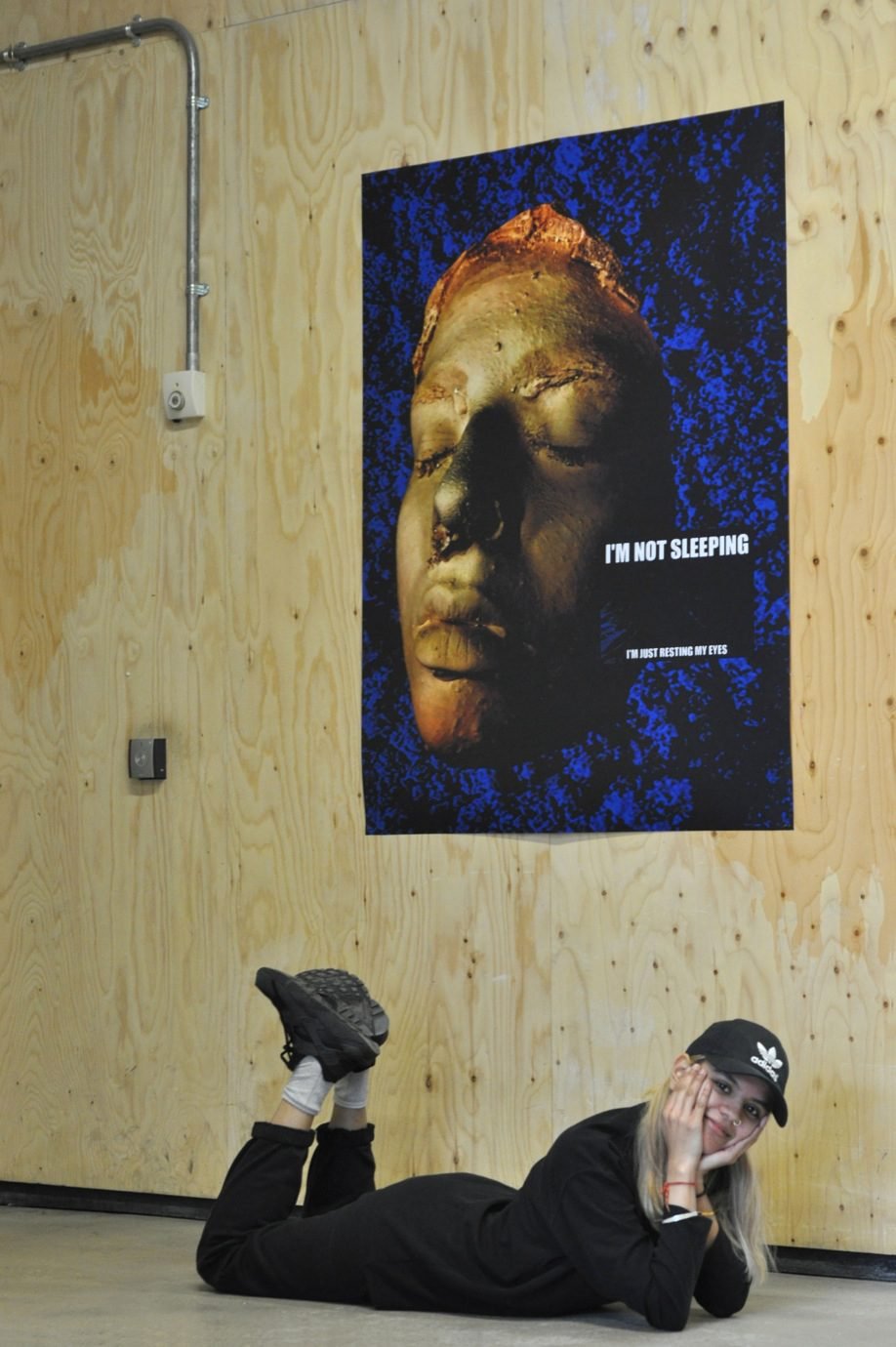

When you look at the entire MA experience, you realise how much you grow in the space of two years. It comes from self exploration and development. There were times when I did not feel like making clothes that day, so I went and sat on the floor in galleries and just listened to David Bowie — you realise that this is part of the process. Taking the time to think, in between moments of intense labour, changed my approach completely. It’s true that when you’re working like a machine you don’t feel your body or mind, so it becomes crucial to walk away and clear your head. I learnt that as much as the RCA developed me as a designer, it also taught me a lot about personal reflection. Having the time to breathe and understand the relationship you have with your work, can inform you of which direction to go next.

How important was it to work with different creative forms?

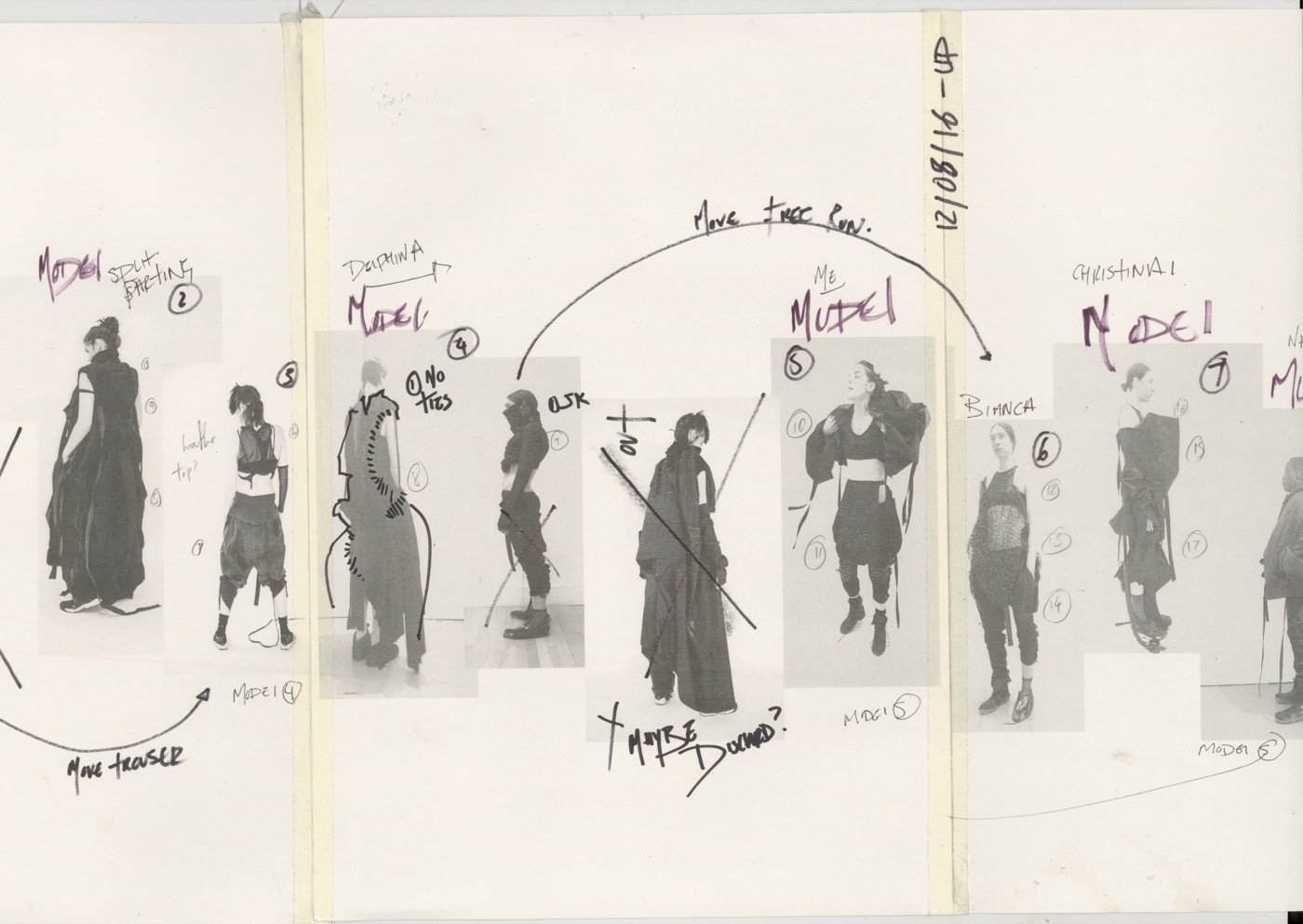

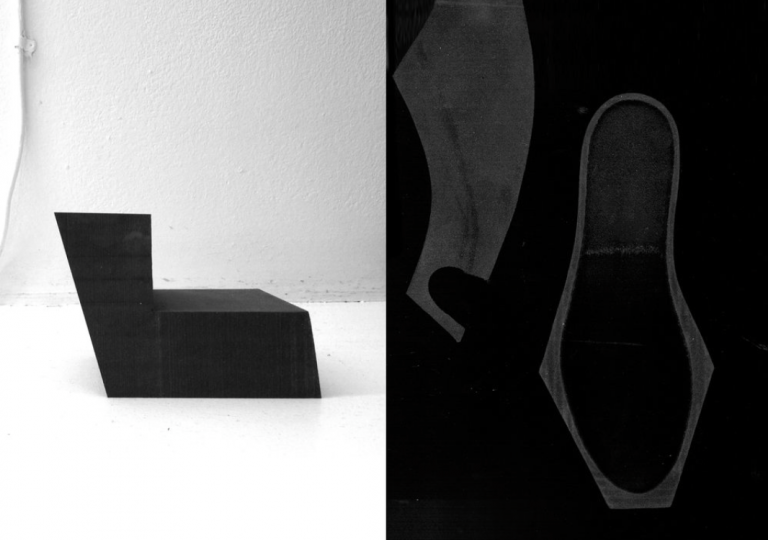

By using different mediums to document your work, your perspective shifts and you begin to see your work as a second person pronoun, as opposed to being so immersed in the first person. Sometimes when you’re working on a project, it’s hard to see beyond the process. When creating the installation for ‘Pack mentality of I’, there were five cameras pointing at me from different angles. I wanted to see the entire space and the way in which my body moved through this 10m by 7m black vinyl flooring entity — otherwise my form, obscured by masses of material, would have been lost. I was able to see different silhouettes forming, hints and glimpses of what my final collection was to be, so I drew them out. I always return to that footage to readjust my expectations.

“I REALLY STRUGGLE TO PLACE MY WORK IN WHAT I DEEM THE ‘INDUSTRY DICTIONARY’, AS MOST OF THE TIME, PEOPLE ONLY CONSIDER DESIGN AS GOOD OR BAD.”

Do you understand your work as design or as art?

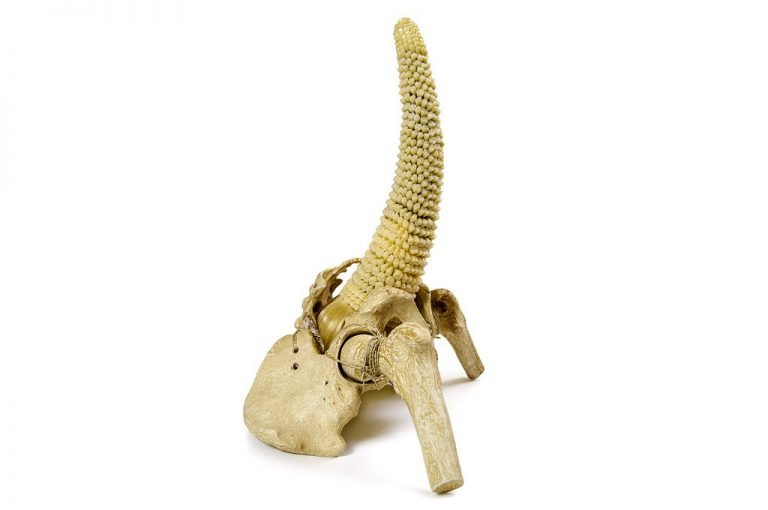

My work is most definitely categorised as design with function, purpose, place and person. I don’t think of my work as art, as I think that’s intangible. My clothes are not weak or feeble things and I like the fact they are used and worn, partly because I designed them in such a way. I was very lucky to be sponsored by a company that gave me loads of old black cotton performance backdrops. They were slightly damaged and stained, but I liked that they had fulfilled their purpose and that I had the opportunity to repurpose them.

I really struggle to place my work in what I deem the ‘industry dictionary’, as most of the time, people only consider design as good or bad. This doesn’t leave much room for understanding or interpretation. So much more needs to be done to broaden the perspectives of fashion consumers and makers — it’s all about access, information and understanding that one must push the boundaries in order to go further. If one only relies on the media that is already in circulation, then we will continue to simply embrace one another’s normalities. Personally I love to find small bodies of text to read and absorb — it might come to me as a reference five years down the line!

Can you elaborate on the industry: your experiences and thoughts?

I think I have a well-rounded understanding of industry. Most of the time I could not intern, as I was either studying or working in retail — the glamourous life! Although working in retail did not inform my practice greatly, it helped to understand building customer relationships and listening to their requirements with regards to garments.

In the places where I did intern, I was lucky to learn about hierarchy, organization and the importance of maintaining business relationships. The most important thing I learnt was the power of persistence: the industry teaches you to always have a solution. If something is not working, you have to come back the next day with an alternative. You have to always be on your A game. This kept me proactive about finding solutions in my own design process.

Within the industry itself, I’d like there to be a greater appreciation of conceptual design in womenswear. I know that our type of consumerism orientates around ‘what you see is what you get’, and I also appreciate the need for commercial design: currently in menswear we see a fusion of both. I think that we truly need to expose conceptual design more. It influences new designers to think differently about their work and how it’s received in the industry.

“I WOULD LIKE THE FASHION INDUSTRY TO BE LESS ABOUT THE SPECTACLE, AND TO BE MORE ABOUT EMBRACING A VARIETY OF DESIGN CULTURES AND WOMEN.”

How do you feel about heading out into industry, are you looking to establish your own brand or work for someone else?

‘The dream’, you mean?! It seems so hard to obtain right now and I realise that I still have a lot to say with my designs. I equally know I am a keen learner, there’s so much to learn about this craft and I would love to get out of London. I would really enjoy working for someone like Rick Owens, Haider Ackermann, Yohji Yamamoto: the pattern-cutting kings!

How’s your experience at the RCA been?

I recently said in a video interview with 1 Granary that my one word summary of my time at the RCA would be ‘mistakes’. Now that I have more time to think about it, I can elaborate: my experience at the RCA taught me that I learnt the most when I got it wrong. Like really wrong, because when you make the mistakes, you instantly know it. You missed your mark, it doesn’t feel like your work. It’s a privilege to know how acute you have become with your work. Then you come back the next day determined to get it right. To move on from that place and do it better, communicate with it harder. The experience has been so valuable in this sense.

How would you like the industry to change?

I would like the fashion industry to be less about the spectacle, and to be more about embracing a variety of design cultures and women. These strong unapologetic women, who do what they need to do. Supposedly this is what our industry is about, the challenge to be defining a new characteristic and inviting the people to wear it. But it’s important to challenge these standards, because it allows the generations to come not to feel threatened by what actually is a really regulated industry. To offer a sincere alternative, a niche to be appreciated. It feels a long way off, but I remain optimistic and hope to pioneer in this way of thinking.