“Not only does all the unsold surplus from the outside world is being sent to developing countries like here, it only adds to anything that’s already not wanted by the locals and ends up piling up into landfills, and basically becomes trash.”

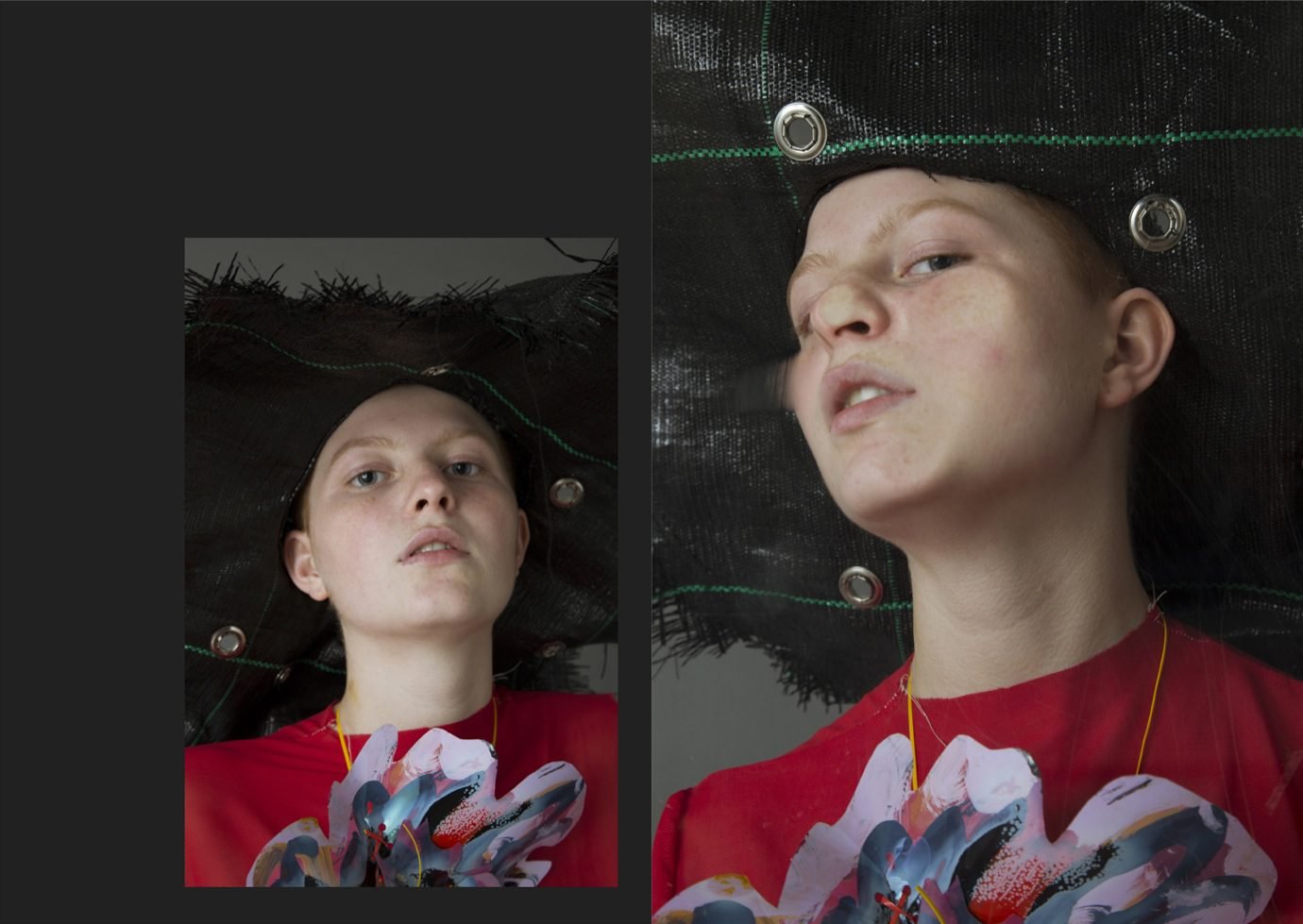

Upcycling planted the seed for what would later become Tiempo De Zafra (TDZ), an overconsumption awareness project that he is now embarking on with his business and life partner, Stephanie Bazzarae Rodrigues, whom he met in NYC. Now based in his native country, they make clothes with what is quickly growing around them— mountains of excess clothing and textile waste.

“What’s happening here is that there’s no service to help recycle clothing,” says Stephanie. “Not only does all the unsold surplus from the outside world is being sent to developing countries like here, it only adds to anything that’s already not wanted by the locals and ends up piling up into landfills, and basically becomes trash.” By observing the residents, the couple realised how they weren’t the only ones making the most out of what they had. One day they saw a taxi driver in a car made out of a variety of different-coloured composites, with one door painted white, another cream, and the others in two shades of grey. After encountering this man, whose name is Agustino, they made a custom shirt out of panels in the same tones of the car’s colours, which is now part of the brand’s permanent collection. They then gave it to him while documenting him riding in his car, asking him about his story of repurposing car parts.

“Poverty is a real, communal issue. So when people work with what they’ve got, it’s out of necessity first and foremost. Repurposing isn’t just a trend here, it’s about making ends meet.”

https://www.instagram.com/p/BxIHnfigh6v/