Drawing on biology, philosophy, environmental studies, and machine learning, Søs Christine Hejselbæk is a truly interdisciplinary designer. “I’m not comfortable being just one thing,” she says, a feeling she’s had since childhood. Growing up in Aalborg, Denmark, she was always creative but also interested in science, which led her to study fashion design at the Kolding School of Design, a program which prioritizes environmental sustainability in the design process. She studied abroad at London College of Fashion for a semester, which reinforced her personal investment in fashion design. “It’s not about beautiful, fluffy things to put on a runway but what problems I can solve.” Immediately after finishing her BA, she joined the Royal College of Art with a firm resolve to think about fashion through science. Entitled Specie, her graduate project does just that.

Søs Christine Hejselbæk on 3D-printing away a carbon footprint

The designer discusses making photosynthetic sculptures for the body

“It was like dancing with fabric frozen in the air.”

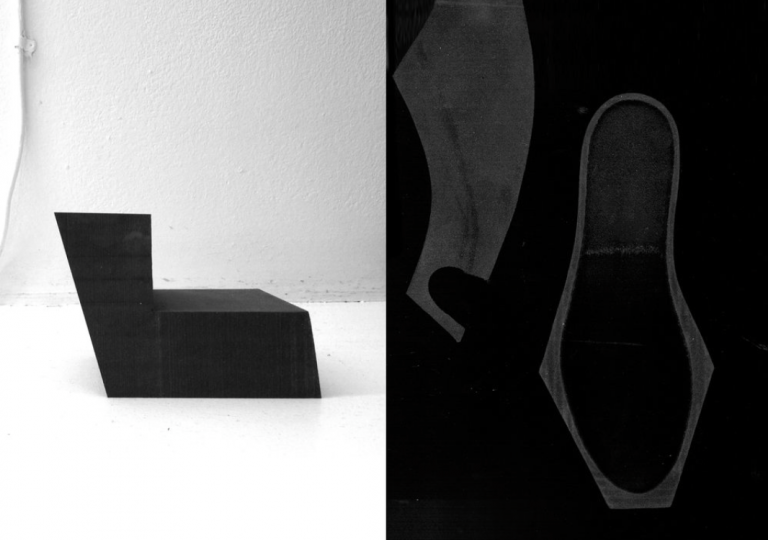

Her research for Specie began in virtual reality. She danced a contemporary ballet piece in a motion capture studio. By way of a software called Gravity Sketch, she translated her performance into digital sculptures shaped by the shifting positions of her hands. “It was like dancing with fabric frozen in the air,” she explains. Aestheticizing the movement of her body, the virtualized performance emerged from her research on proxemics, particularly how people perceive the space between their bodies and their environments. By 3D-modeling her movement on-screen, she gained a deeper awareness of her spatial embodiment.

Her digital imaging didn’t stop at the Gravity Sketch drawings though. It would have been too literal, too humanistic, to directly interpret her motion into garments. So she decided to abstract the performance a few degrees further from herself in a critical investigation of her own agency as a designer. Hejselbæk converted her digital sculptures into parametric 3D models, which can be programmed to automatically generate modified versions. Working closely with a technician at the RCA, she developed a machine-learning algorithm based on a dataset of how networked rivers flow into one another. The algorithm synthesized that data into a fractal growth system, which works much like how crystals form. At the end, she was finally able to feed her parametric models into the algorithm, which created a porous, intricately-webbed surface texture based on the river networking.

The fractal structure also pays homage to interdisciplinary scholar Donna Haraway who wrote ‘A Cyborg Manifesto’, the cult feminist essay eroding the divides between human, animal, and machine. Hejselbæk took inspiration from Haraway’s more recent concept of ‘tentacularity’, which to her means “the idea that all species are connected in a massive 3D web.” In that sense, the algorithm-processed sculpture symbolizes the interdependency that holds ecosystems together.

Hejselbæk originally planned to 3D-print three digital sculptures. Then the pandemic struck, leaving her unable to use the school’s facilities. So she improvised, deciding to make just one look using a handheld 3D-printing pen. It took a lot of planning before she could begin. She projected the 3D model onto her mannequin, carefully rotating it around and padding it until the silhouettes matched from every conceivable angle. Only then could she start drawing out the sculpture in precise mimicry of the projected design. It took her a week to complete.

She crafted the sculpture out of a biodegradable cornstarch-based filament. After it was complete, she suspended it in her shower and infused it with spirulina algae for a luminous green tinge. The algae are also functional, purifying the air through their process of photosynthesis, which will eventually offset the sculpture’s carbon footprint of 125 grams. “It’s like planting a tree around yourself.” For comparison, a white cotton t-shirt might have a footprint of around 8 kilograms, she says.

In her dissertation, Hejselbæk references a theory by the Roman architect Vitruvius which posits that all constructed forms live somewhere between vesnutas (aesthetics), utilitas (functionality), and firmitas (durability). Vitruvius believed an ideal structure would embody all three equally. She decided to modify his triad into a quadrant by adding a fourth virtue: sustineri (sustainability). “I have placed my work in the middle of this new model,” she writes, “as I feel that I have taken all four aspects into account at an equal level in an attempt to create an expression that challenges the role of the body in space, but also celebrates it.” Indeed, the sculpture she created in the end was shaped by her movement, texturized by river data, and crafted by her hands – a deep synthesis of body, space, and environment.

“You have to start somewhere,” she figures. “You have to change the system from the inside.”

Deeply invested in combating pollution and carbon emissions, Hejselbæk grapples with the ethics of joining the fashion industry. Though she currently works freelance as a digital designer, she’s amenable to the right opportunity in fashion design. “You have to start somewhere,” she figures. “You have to change the system from the inside.” But designing for high street brands doesn’t exactly beckon.

“I am optimistic just because I think the world is gorgeous.”

She’s equally ambivalent about the future of the planet. Humanity has enacted potentially irreversible damage to the planet, but it has so far managed to endure epochs of intense climate. “I am optimistic just because I think the world is gorgeous,” she says. With or without humans, “nature will prevail.”