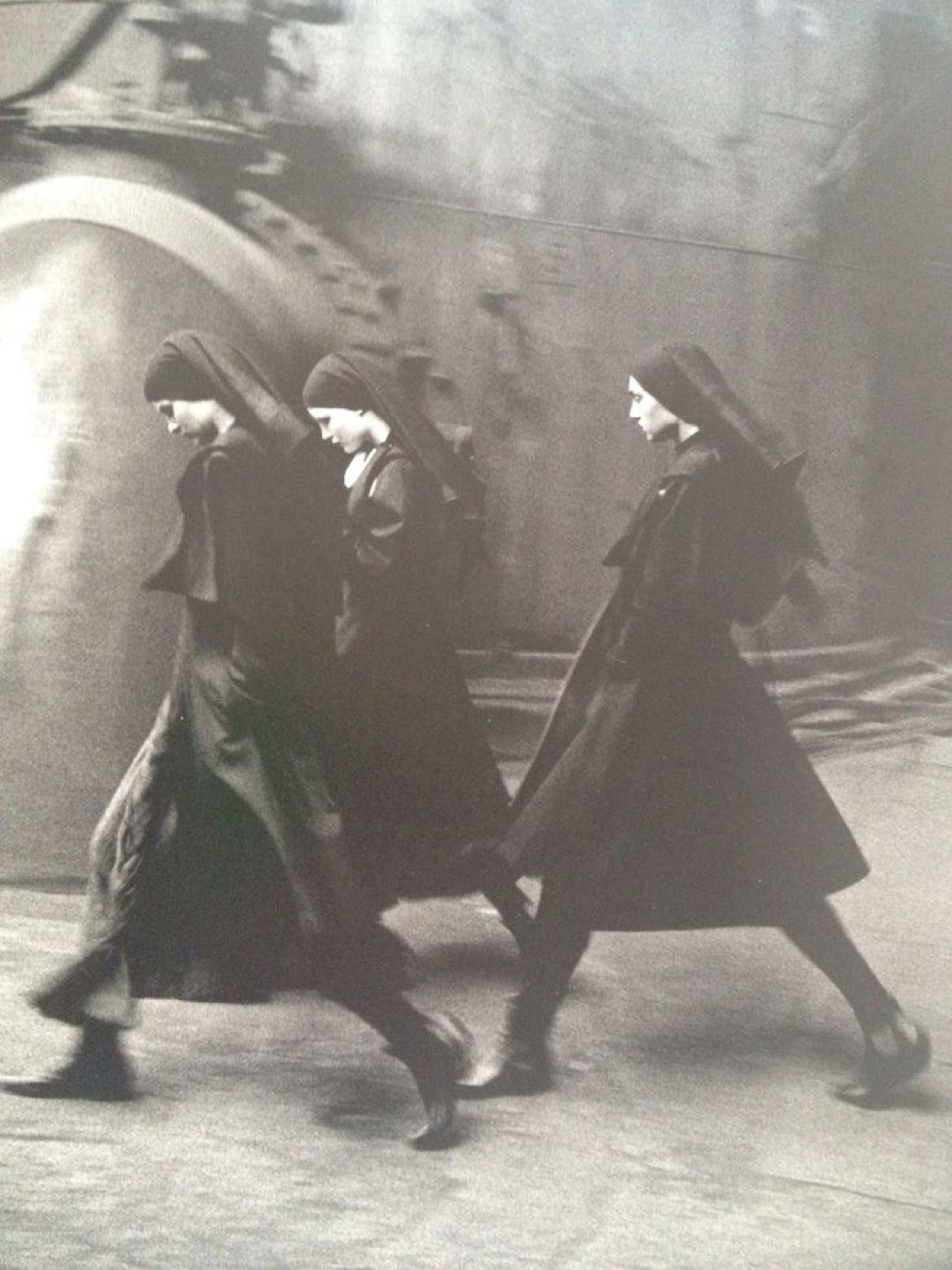

A literature and fine arts graduate of Tokyo’s prestigious Keio University, it would not be overly audacious to highlight the parallels between certain literary works and the work of Comme des Garçons founder Rei Kawakubo. Indeed, I would not be the first to do so. In her 2005 feature on the “Japanese avant-gardist”,published in The New Yorker, Judith Thurman situates Kawakubo’s game-changing 1982 ‘Destroy’ collection in a context “much more Parisian than it seemed – a piece of shock theatre in the venerable tradition of Ubu Roi”, Alfred Jarry’s seminal precursor to the Theatre of the Absurd. Though home to institutions such as the Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture, with its almost dictatorial regulation, Paris has long been renowned as a nesting place for the avant-garde, producing warp-minded geniuses in a multitude of fields: theatre, literature and visual arts to name a few. The collection itself, an ascending of bedraggled crow-black figures draped in seemingly moth-eaten knitwear, stunned the French press, giving rise to the moniker “Hiroshima chic”, a somewhat problematic allusion of a relationship between Kawakubo’s earth-shattering Paris debut and one of the most devastating events witnessed by human eyes. Yet, though grounds for analysing the collection in light of Hiroshima are rather tenuous, tropes of destruction evidently pepper her work.

“THE DISTINCTIVE INEXPRESSIBILITY OF KAWAKUBO’S APPROACH LIES HERE, IN THE VISUAL DISSONANCE BETWEEN WOMAN AS SEXUAL OBJECT AND WOMAN AS MOTHER”

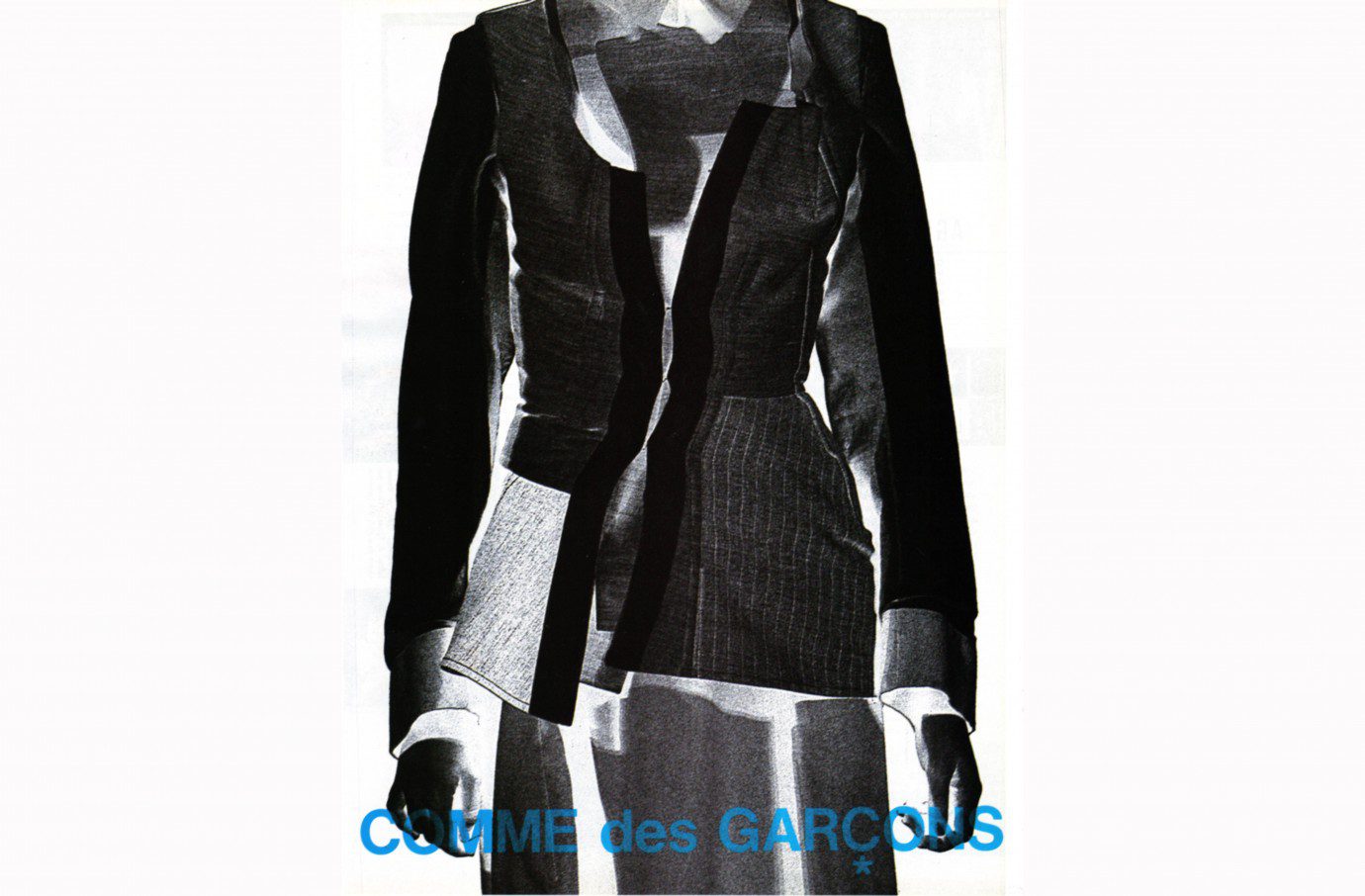

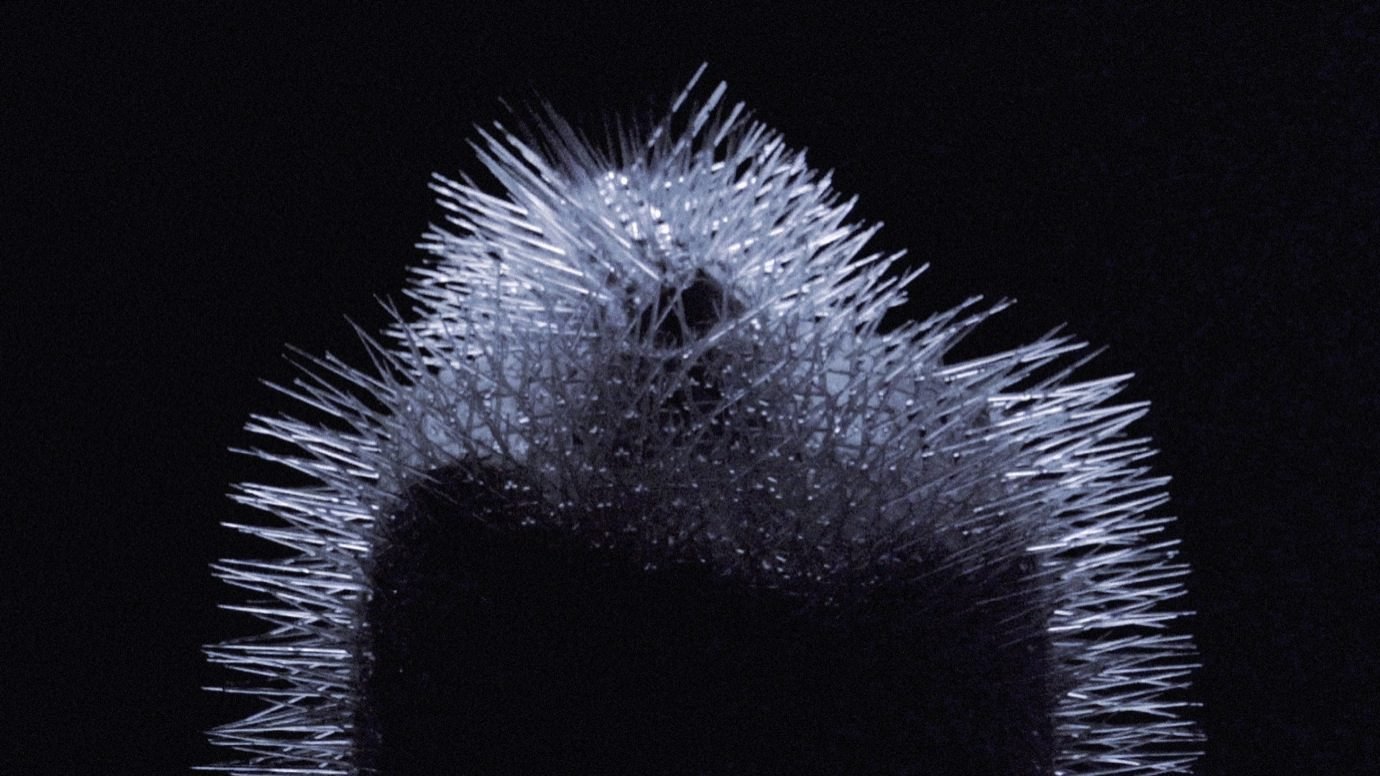

The Kawakubo aesthetic revolves around a central inexpressibility, implementing a relentless system in which fabrics and techniques are destroyed and appropriated, exposing an eerie silence in which the most essential creative inspiration lies. A glance at the 1997 ‘Lumps and Bumps’ collection reveals this, with dresses in clinging silks and checkered fabrics disfigured by tumorous lumps, simultaneously accentuating and obscuring the female form, contorting breasts, hips and buttocks to comic proportion, effectively satirising the sexualisation and commercialisation of the body in the fashion industry. In a particular look, she goes yet further in challenging constructed notions of femininity and interrogates the institution of motherhood, presenting a model wrapped in a svelte scarlet cocktail dress, an oversized protrusion that eerily resembles a swaddled child bound diagonally across her chest. The distinctive inexpressibility of Kawakubo’s approach lies here, in the visual dissonance between woman as sexual object and woman as mother; the exposure of the chasm between these two archetypes of womanhood acts as the unveiling of a societal inability to provide attainable standards of beauty for those that lie outside of these constrictive paradigms. Yet Kawakubo does not aim to create a new, more encompassing standard of beauty for the marginalised masses; instead, through manipulations and juxtapositions of fabrics, silhouettes, images and symbols, such as the contrasting of scarlet, a colour laden with connotations of sensuality, passion and violence, with a silhouette emblematic of maternity, she creates clashes that expose a void in which this beauty lies. Under Kawakubo, the rigidly dogmatic symbolism of conventional fashion loses value, birthing what has been heralded as an anti-fashion, a fashion of ‘madness’. Indeed, such laden terms pose a series of conundrums and paradoxes, for in order to discuss her work in the objective terms that contemporary fashion discourse necessitates is to completely eschew the nuance of her work. One could even go so far as to claim that discussing it using the prescriptive construct of language inevitably rationalises, and ultimately glosses over the quintessential unspeakability that lies at the heart of her oeuvre.