Vestoj 5, On Slowness

“HOW DO YOU JUDGE SUCCESS AND FAILURE IN FASHION TODAY? IS IT OK TO DROP OUT? WHAT WE UNDERSTAND SUCCESS TO BE WITHIN THE FASHION INDUSTRY TODAY IS RATHER LIMITED: THERE IS ALMOST A BLUEPRINT FOR GROWTH THAT DESIGNERS SHOULD ADHERE TO IF THEY WANT TO BE CONSIDERED SUCCESSFUL.”

All this to say that whether I publish the Vestoj Journal or create a Vestoj Salon, I see my role as bringing a more considered approach to fashion. I want to bring scholars and practitioners closer together, and create a dialogue between different ways of understanding fashion. Sometimes it can be entertaining and emotional and sometimes it requires focus and intellectual work, but ultimately I’m hoping that my work will encourage academics to interact more with industry people, and for fashion practitioners to feel that fashion theory is a helpful way to understand this industry, rather than intimidating or irrelevant.

Mostly Sara, a bit of Jorinde: Why do you think we still tend to separate the figure of the scholar and the artisan or artist? Theory and practice? Of course the process of production implies that you use your hands, your body; you’re doing an intervention in the matter. But, during this process, one is constantly making decisions, privileging certain ideas over others, creating and mobilizing meaning.

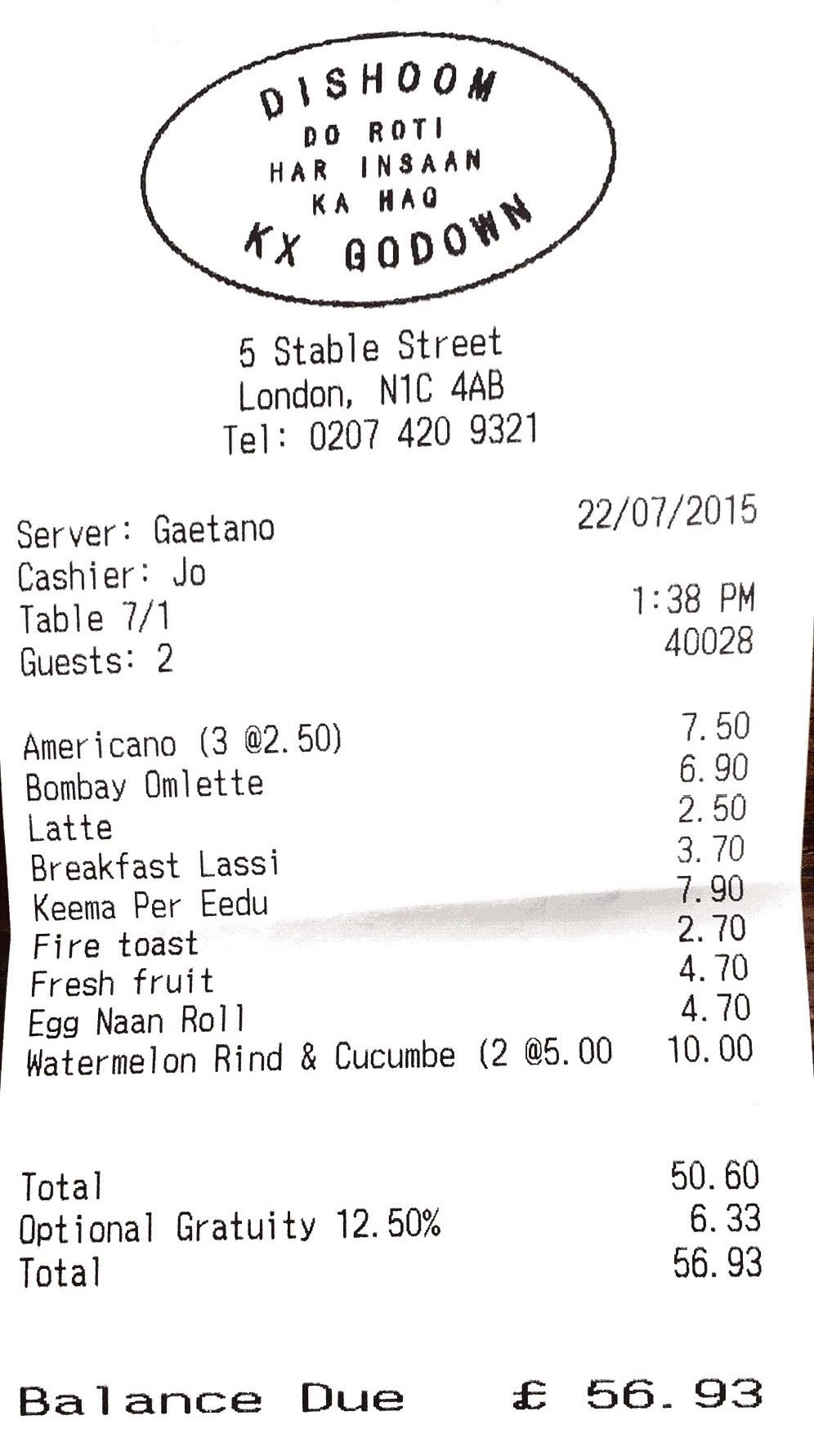

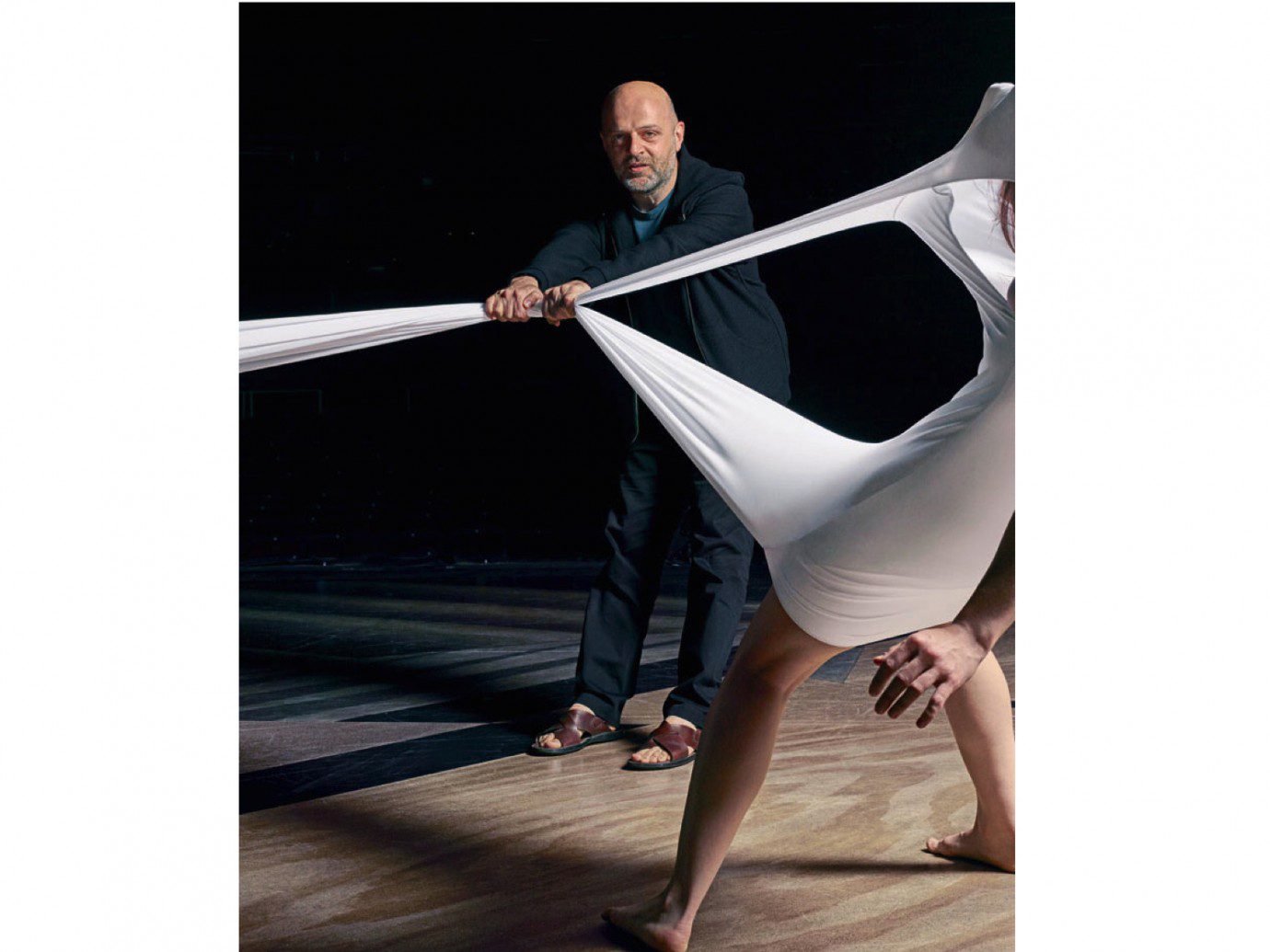

I think that it is because fashion is always oscillating between creativity and commerce. The relation to commerce and the importance for designers to produce collections that can be readily sold, perhaps at times hinders them from putting their work in a more conceptual context. In a recent interview we did with Hussein Chalayan for example, he seemed to be very strongly rebelling against being labelled a ‘conceptual designer’. It was as if he felt that the label has worked against him in the industry, perhaps by making store buyers intimidated when engaging with his work.

It can be an act of reductionism, if you think about it. To say that there are designers, and then ‘conceptual designers’, might be a way of implying: well I’m not going to try and understand what he is doing because he’s conceptual. What does concept mean here? We need concepts to speak and think, we use them all the time. So, if we consider the conceptual designer to be the one who is aware of the fact that he uses concepts that potentially implies that the other designers are ‘innocent users of concepts’. This innocent creator is a bit problematic for me, more if we understand that he is proliferating certain images and not others, and that is a political decision. But then very often it is omitted that representations have a political charge. I think that is really dangerous.

There are designers that approach their work as a product, as if it was yogurt or toothpaste or any kind of consumable goods. But, as you point out, that doesn’t mean there isn’t a concept or an agenda behind it. Being a designer is to impress your vision of the world on the consumer after all, and as such of course it’s ideological, if not political. I don’t think it’s a problem that there are designers who are also businessmen, or even that fashion has been so susceptible to corporate business. The problem is when the other side of the spectrum gets pushed out, or is under threat (as seems to be the case right now), and the emphasis is only on commerce and work that is easily accessible and understandable.

We’ve just completed an issue of Vestoj that deals with failure. One of the many things that I had in mind from my interview with Chalayan, was that he feels let down by the system. Does that mean the system has failed him, or that he has failed to achieve success on his terms within the system? How do you judge success and failure in fashion today? Is it OK to drop out? What we understand success to be within the fashion industry today is rather limited: there is almost a blueprint for growth that designers should adhere to if they want to be considered successful. For example, starting to show collections with a support scheme like NEWGEN, winning a prize issued by a corporation, eventually having your label acquired by a conglomerate group and going on to design for one of their houses whilst retaining your eponymous brand – this appears to be what we expect from our successful designers today.

It’s a dream for a lot of people.

It’s a dream because that’s what ‘success’ today is. And with it come wealth, fame, status and access to other successful famous people.

At the same time there’s a sort of transtemporal sense of success, which is probably the success of this figure who is not totally inscribed in the active system of the moment in which s/he’s living. But then, there is a success because it survives, it gains or creates a space in the understanding of what fashion can be.

Though that is scant consolation if you’re struggling to pay the rent, or deliver your collection on time. It’s also worth bearing in mind that the kind of legacy you’re implying often comes because we tend to rewrite the past, and romanticize someone’s life and work according to attitudes that also shift and change with time. If today we, for instance, see booming business as a sign of success, we also think of the past as ‘better’ or ‘purer’ – a time when artist-designers were celebrated. It’s quite schizophrenic actually. We mourn and long for a lost, ‘authentic’ past and values that we at the same time don’t encourage in our contemporary designers. One of the articles in our upcoming issue is about queer designers and the ‘hero’ myth that often exists around them. This narrative always incorporates great adversity, followed by great success and usually ends in tragedy. Think of Charles James, or more recently Alexander McQueen. John Galliano too, to an extent. These designers were often a pain to work with at the time, inflexible and demanding – loose canons, as one industry insider I interviewed pointed out. My point is that the designers from the past that we celebrate today often symbolize something we feel that we’re currently lacking. That their work survives, or gets rediscovered, isn’t necessarily only a sign of how great it was or is. It’s also a sign of how we want to see ourselves today.