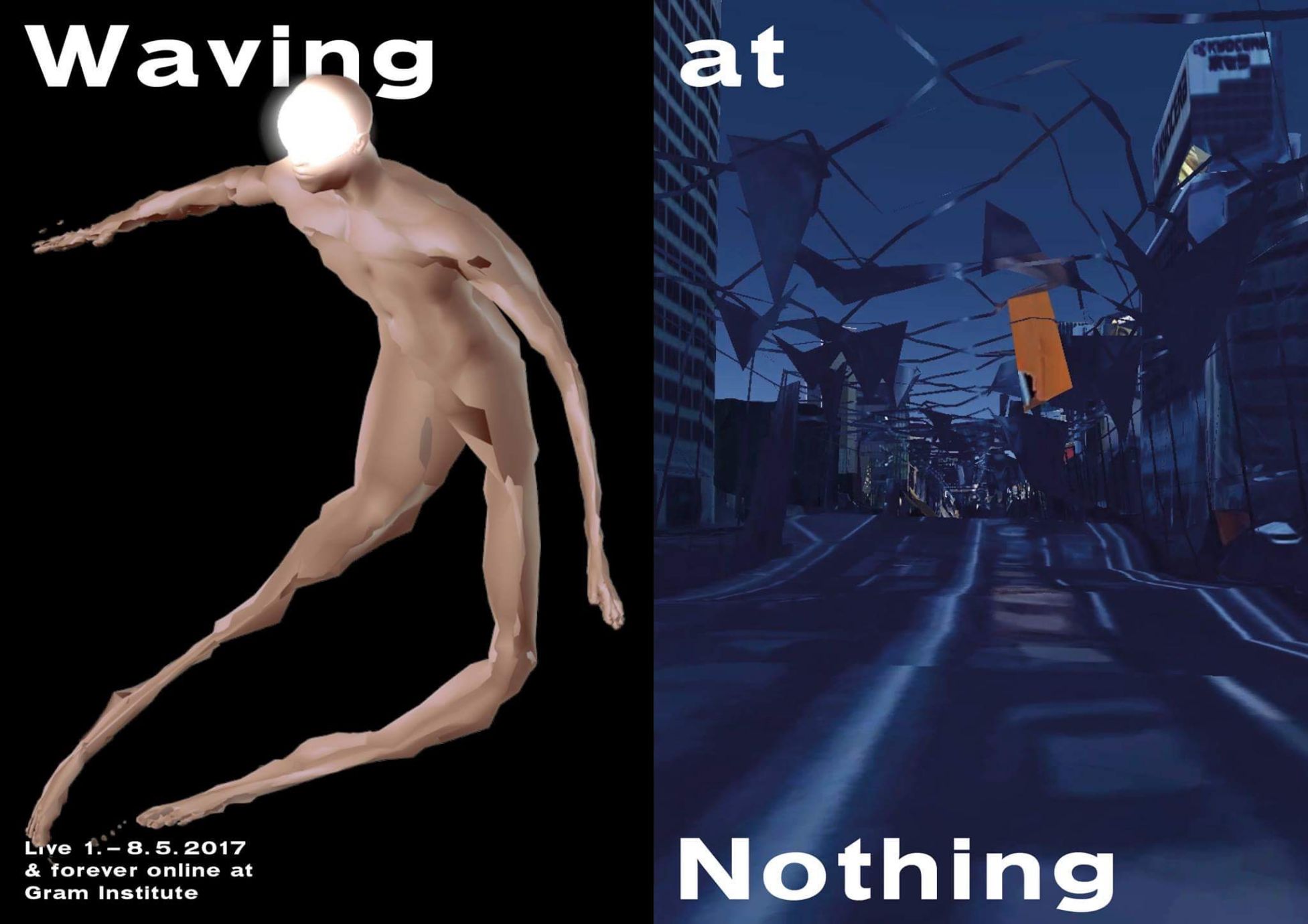

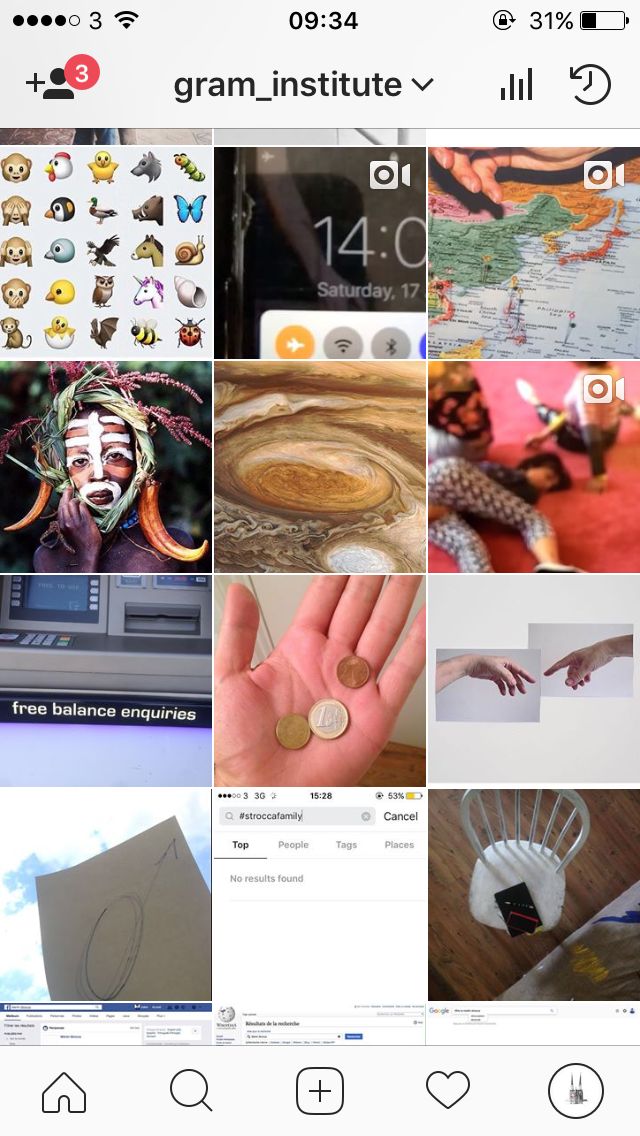

Welcome to the Gram_Institute. This newly-opened, multidisciplinary online gallery is an artistic space of exploration. Carefully curated through Instagram, the Institute exclusively showcases authentic and original works, formerly unseen by the public eye. Practitioners from various artistic fields are given the opportunity to create something truly unique. With seven days to experiment with sound, colour, dimensions and dramatic theatre, the Gram_Institute encourages their creativity to run free. From the online characters of Diogo de Tita performing a live dance macabre and the virtual disembodiment of reality by Nils Braun, to french artist Julien Deransy questioning the role of the art curator himself, the instagram account analyses our online realities and new understanding of art.

Scrolling through art with the Gram_Institute

Martin Strocca, founder and head curator of the newly-published Gram_Institute Gallery, talks us through the importance of authenticity and what the future of art distribution looks like.

When I first spoke with Martin, he immediately read this quote to me. Taking his time, he read each line concisely and with intent. He paused, putting down the paper. This, he said pointing at the sheet, is why we live in the most exciting time to be alive.

The Gram_Institute was born intuitively, during a phone conversation with artist and CSM graduate Will Webster. They began talking about “the virtual space and how art can occupy it,” a topic directly relating to Will’s ongoing research, who was initially drawn to the project due to the “locationless space” and the way in which it “offers an intriguing way to engage in cultural production – where physical space is gratis, the value of time becomes clearer.” Both Martin and Will discussed the importance of authenticity and authorship. They both believed that collaboration is increasingly important as “space resources become commodified.”

Scrolling through the gallery’s timeline, it becomes immediately clear that Martin is pushing the boundaries of what it means to exhibit art. Every image you see draws you in for a closer look, the images are textured, layered, manipulated and transformed into something one-of-a-kind. Martin stresses that we must not forget that when we post art on Instagram, we aren’t actually posting art. We are publishing a reproduction, or a perception of a specific museum. Martin is especially fascinated by “how art is being disseminated within social media, and how works are being experienced, viewed and essentially judged.” His reasoning for creating the Gram_Institute stems from his interest in understanding what impacts this re-publishing of online art has upon the spectator, and how in many cases “reproductions can give a better experience.”

Martin gives the example of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, exhibited at the Louvre Museum in Paris. Over 6 million people visit the Mona Lisa every year, and yet “the journey to go see the painting can be more exciting than seeing the painting itself, because you don’t really see it.” In fact, if you really want to see the Mona Lisa up close and experience its intricate details, perhaps it’s better to consult a reproduction. Replicas allow you to “easily see it’s delicate features, with the added ability to zoom.” Essentially, the greater level of freedom that comes with interacting with a reproduction, allows the audience to better grasp the feeling of the artifact, more so than the original has to offer. One of the artists featured on the Gram_Institute is Evelyn Bencicova, who created a body of work in collaboration with Adam C. Keller, focussing on the weight that authenticity holds. Bencicova articulated that she finds the new conceptual way of playing with authenticity “very daring, almost critical in the times when high art refuses internet as a medium.”

“IN THE BEGINNING ART WAS FUNDED BY THE CHURCH. SOON AFTER BY THE POWERFUL AND THE WEALTHY, AND EVENTUALLY BY THE STATE. TODAY THE LARGEST COLLECTIVE PATRON OF THE ARTS IS THE FACELESS CROWD-FUNDING POPULATION OF THE INTERNET. IMPORTANT PORTRAITS ELEVATE THESE SEEMINGLY INVISIBLE PATRONS, TRANSFORMING THEM INTO HYPER-AUGMENTED VERSIONS OF THEMSELVES: A GENERATION CAPABLE OF CHANGING THE WORLD.” – JEREMY BAILEY

The concept of the Gram_Institute came from this idea of wanting to provide original, authentic artworks that can be published using Instagram. Martin naturally seeks for originality in everything he does and the timing of this project couldn’t be more appropriate, especially as our culture becomes increasingly obsessed with authenticity. For Martin and his colleagues, this notion of legitimacy remains at the centre of their focus as “the works are only validated once they have been uploaded to the Instagram page.” In some ways the works lose ownership, because after all, what is being owned when it is being shared? Martin emphasises the importance of “moving away from the possibility of being commercialised,” as one of the main benefits of a virtual gallery is this ability to keep the page democratic. The only way it could be commercialised is if the password and username were bought by a museum or collector, who would keep the gallery accessible in its entirety. No work can be bought individually.

The entire experience is meant to be shared, not owned. Martin recalls the initial development process of Gram_Institute and how it involved copious amounts of “skype meetings between artists and designers.” The beauty of this creative space remains in the fact that it is constantly evolving, even today. It has no defined structure or format, as that would be besides the point. There is no intended final picture when it comes to the Gram_Institute, it is a never-ending work in progress.

Martin provides the artists with the option to choose how many pictures to post and what the focus of their exhibition will be. When asked how he decides what works to publish, Martin reveals that they are interested in having a plural response of how this space can be occupied. One of the most attractive things about a virtual gallery, is the ability to freely experiment and explore different options. He believes that “an internet-based gallery doesn’t need to have a post-internet aesthetic,” which is why each exhibition strives to explore an idea or in some cases a material, by taking an entirely different approach.

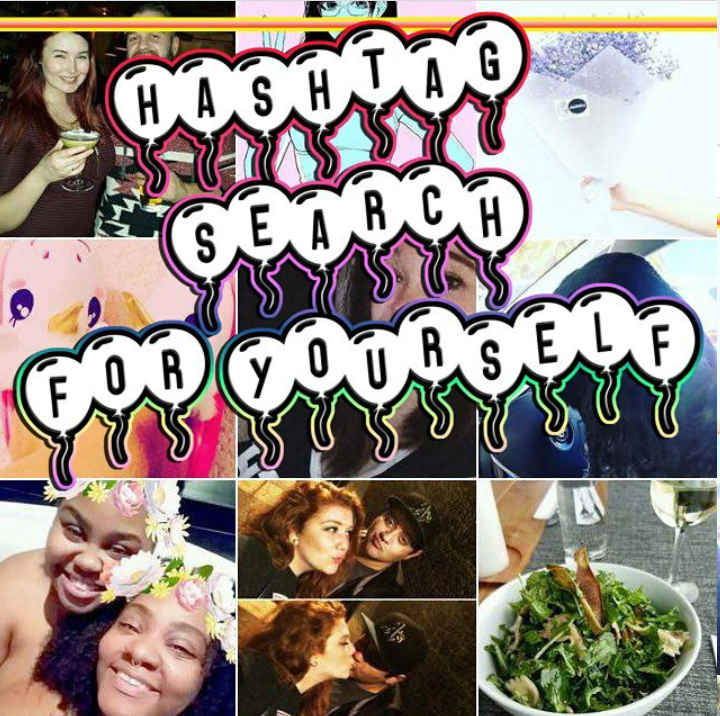

Sara Graca’s exhibition ‘Oh So Many Right Now’ focuses on the capacity of the hashtag, using the art of collage to combine and reveal the extensive volume of images that populate Instagram per hour. The following exhibition by Nicola Lorini, explores something entirely different. Lorini “decided to produce a series of photographs overlapping fragments of artefacts, collected with a group of mudlarks on the Thames shore.” Lorini is experimenting with the temporal importance of virtually published art, he believes that once an image is posted it loses its original momentum. He understands the movement surrounding an art piece to be an important part of the work itself, and therefore asked Martin to “post these images day by day in the same hour of the lowest tide of the Thames, creating a link between the digital decisional appearance of the images on Instagram, and the moment of the day where the riverbed emerges from the water.”

Lorini created five external characters “with personal Instagram accounts, some of them very institutional like Dr. Ronda, Associate lecturer at Maryland University.” They were created with the intentions to intervene daily with his posts “by establishing a set of alter egos of myself, commenting and reflecting from different perspectives,” Lorini said. These alter-ego’s share comments, emotions, memories and stories on the images of spiritual statues and tribal Gods. Consequently, by having characters that continue to contribute and re-analyse his works, Lorini is finding new ways of keeping these archived works alive and ‘fresh’ in people’s minds. Despite the images being several days or weeks old, “their comments will manifest in the future, reactivating the content of the images, changing or re-contextualising it.”

The Gram_Institute is inspired by facing challenges such as “how can performance and design be experienced on instagram?” Motivated by the need to create a space where all of these artistic mediums can be universally enjoyed, a place where dance, theatre and art can be exhibited side-by-side. Martin goes on to tell me that “it is also important to say that it is a shy space at the moment, quite invisible in fact.” It’s current exposure is a direct paradox of what Instagram essentially is, with a reputation of being such a viral platform.

Martin articulates the importance to talk about instagram itself. It is a very interesting and diverse space with all sorts of rules and regulations, it is a much more politicised environment than you may think. For example “why is it that you can post male nipples but not female nipples?” It is a space that has instantaneous access, you can just pull out your phone, press a button and scroll. Martin compares this accessibility to a virtual museum website, where you would have to actively search and enter information to find what you are looking for. Whereas for Martin, the appeal of using Instagram “is that instantaneity.”

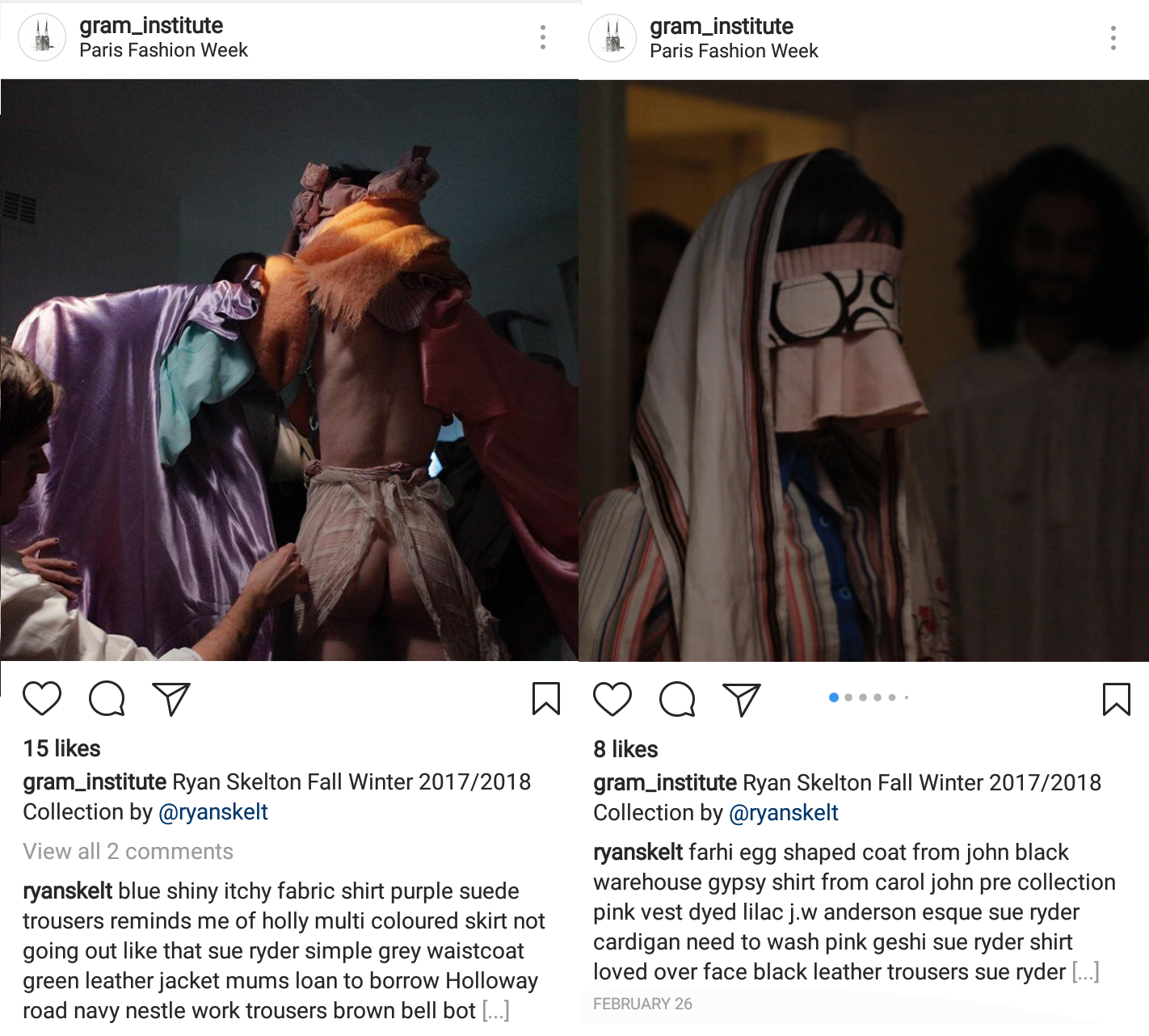

Instagram also gives us the option to manipulate location, and this is something the Institute is currently exploring. For example “Ryan’s skeleton performance was actually shot in December in London, but it was uploaded in February with the location of Paris.” Martin reveals how it was not an instantaneous process at all, and that most of the work is planned. This makes the viewer question if it’s even valid.

Using the example of Ryan’s performance, Martin demonstrates that with many of the works, the quantity of posts published depend on the artist’s message. Having been interested in fashion since a young age, Ryan’s motive was to occupy the space by “creating a fashion show performance using all of my wardrobe.” Ryan’s production was about being physically dressed and undressed, being manipulated in a space by his audience and it is entirely centered around overindulgence. As his message is of excess, desire, and the insatisfaction that comes with buying clothes, it makes sense that the “posts are also in excess and in total overload.” To Ryan, “Instagram is dominant in the way I feel most people consume images today,” this relates to the enormous excess of information that is constantly overwhelming and almost unavoidable.

The Gram_Insitute page is in a constant state of flux, and it is important to its creators to keep the archive active so that the public can keep accessing and interacting with their shows. Part of the Institute’s focus is centered around “the future of personal profiles and exploring what it means to have an archive that continues to grow.” Martin recalls the use of MySpace several years ago, and questions what happened to all these previous tools that we once had, what happened to all this information? And what will happen to this information we are publicizing now in this space? It is not solely about what shows are published next, it’s about what has been previously explored and the causal relationship between the two.

Another artist featured on Gram_Instutute is Dario Srbic. His occupation of the space was inspired by the “impact of ubiquitous image production and dissemination on photography and the currency of the image.” When Srbic was approached by Martin he was extremely excited to become a part of the project as it is directly dealing with the collapse of real, three dimensional space, as the sole vehicle for the dissemination of artworks. Srbic was specifically attracted by this process of “taking the curatorial space into the virtual, self-propagating dimension.” Srbic’s occupation of the space was centered around “the ephemerality of the regard in virtual realm by posting images of a blink of a person.” As we know these blinks last just an instant, and it can be compared to the “approximate average time Instagram users take to dwell on shared images.”

Accessibility is another essential element to the Gram, “it’s about the open access of the page” as it allows anyone anywhere to be a participant. In that sense it is democratic, you are observing the original, no matter where you are or what device you use. Martin clarifies that it never has been, nor never will be the intention of the Institute to over-pollute, but instead be a catalyst to generate self-reflection. Their motive is to create content in terms of what they are trying to explore, whilst using the countless creative possibilities that Instagram has to offer. When asked if he believes society is becoming increasingly desensitized to images today, Martin references Sara Graca’s inquiry into the hashtag. He goes on to explain that the most popular hashtags on Instagram can change and be updated within seconds. If you search for the sunset hashtag on Instagram and then mentally remember one image that is just posted; after 2 minutes you will have to scroll 100 images to find that sunset. After 5 minutes you will have to scroll 300 images, and after 10 minutes you may never find that image again. So in that sense, “there is definitely a loss in the meaning of images” as the pace of our visible life moves so violently fast, that it eventually loses significance.

Whilst contemplating the future of social media and it’s impact upon the distribution of art, I ask Martin whether the digital space will ever replace the physical gallery. Martin it quick to respond, expressing how “as long as we have the physical, it will never replace” and nor should replace. Both spaces are full of possibilities and one should not try to oust the other. Of course these two elements can be combined, “but they can also exist separately.” Martin explains how the structure Gram_Institute is heavily influenced by how physical art institutions are organised, playing with the role of the curator and with the necessary administrative duties. However, it is important that there is a “space for both the virtual and the physical to exist” and not to think that one can overpower the other. If we are all turned into algorithms then maybe, perhaps, but as long as that doesn’t happen, both spaces will continue to coexist and overpower together, rather than against each other.