What is the hardest part of being a set designer?

I think it would be very different for everybody, but for me it’s flying. I’m trying to tell myself that I love flying, but that’s one thing I don’t like about my job. It also means that the things I build are either not with me (they are in a different country) or have to come with me on a sort of very tricky course. That often gives a lot of stress, because it means that you think: “Shit I have to build something massive over there.” It’s what causes most of the problems, really.

How do you transport the massive pieces that you build?

If the budget is low, we sometimes have to flat pack it in boxes and put it in freight in the Eurostar, and then I carry the rest of it with my team. If there is a big budget, there’s a big truck that drives us there, or it gets shipped over, but generally there’s not enough time for that. Everything is always really last minute, no matter how organized you are – there’s always some really time-sensitive things. We pack a lot of things in suitcases, it’s really not practical.

Can you describe the preparation process from start to finish for a typical window display? How do you manage your time and how long does an average job take to complete?

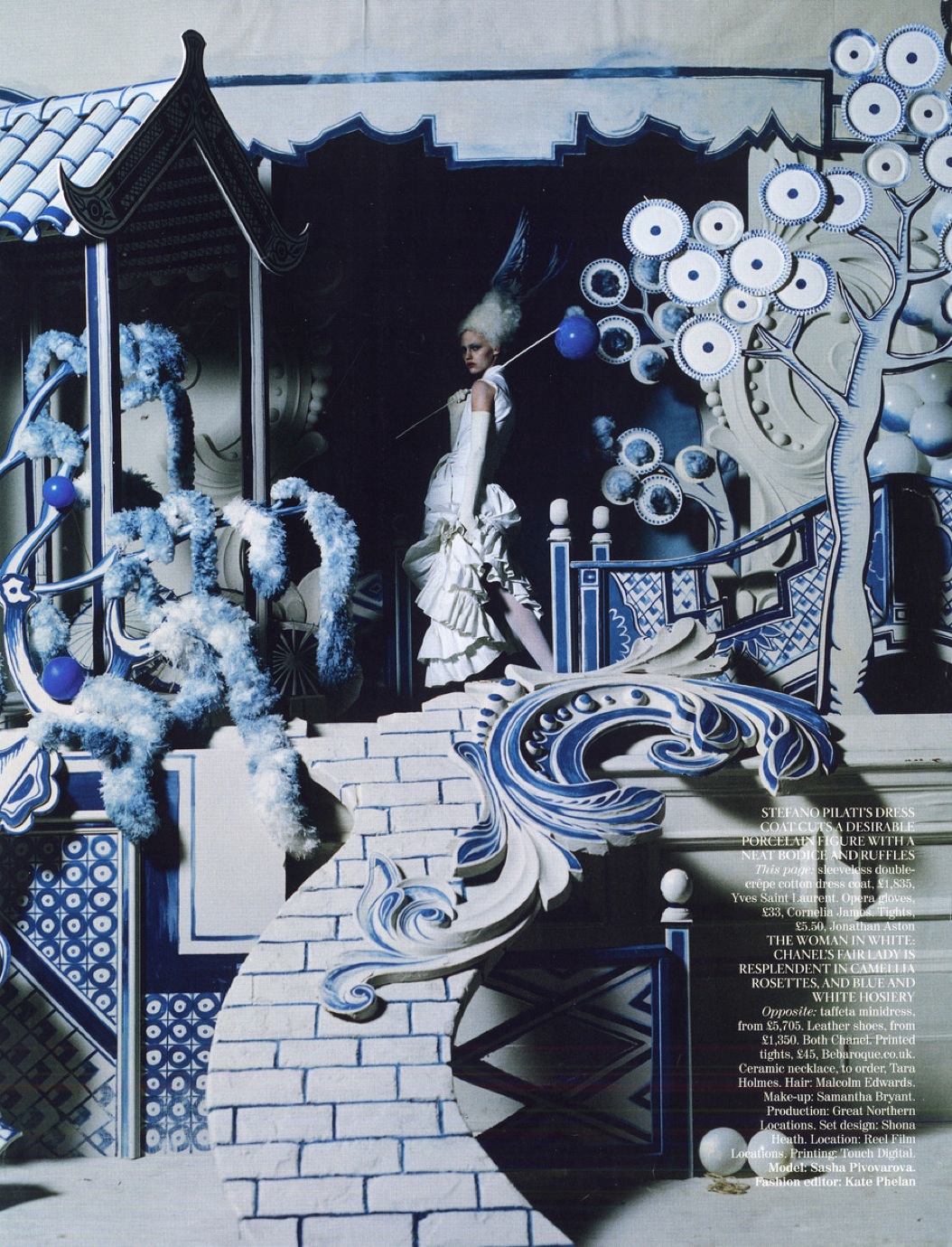

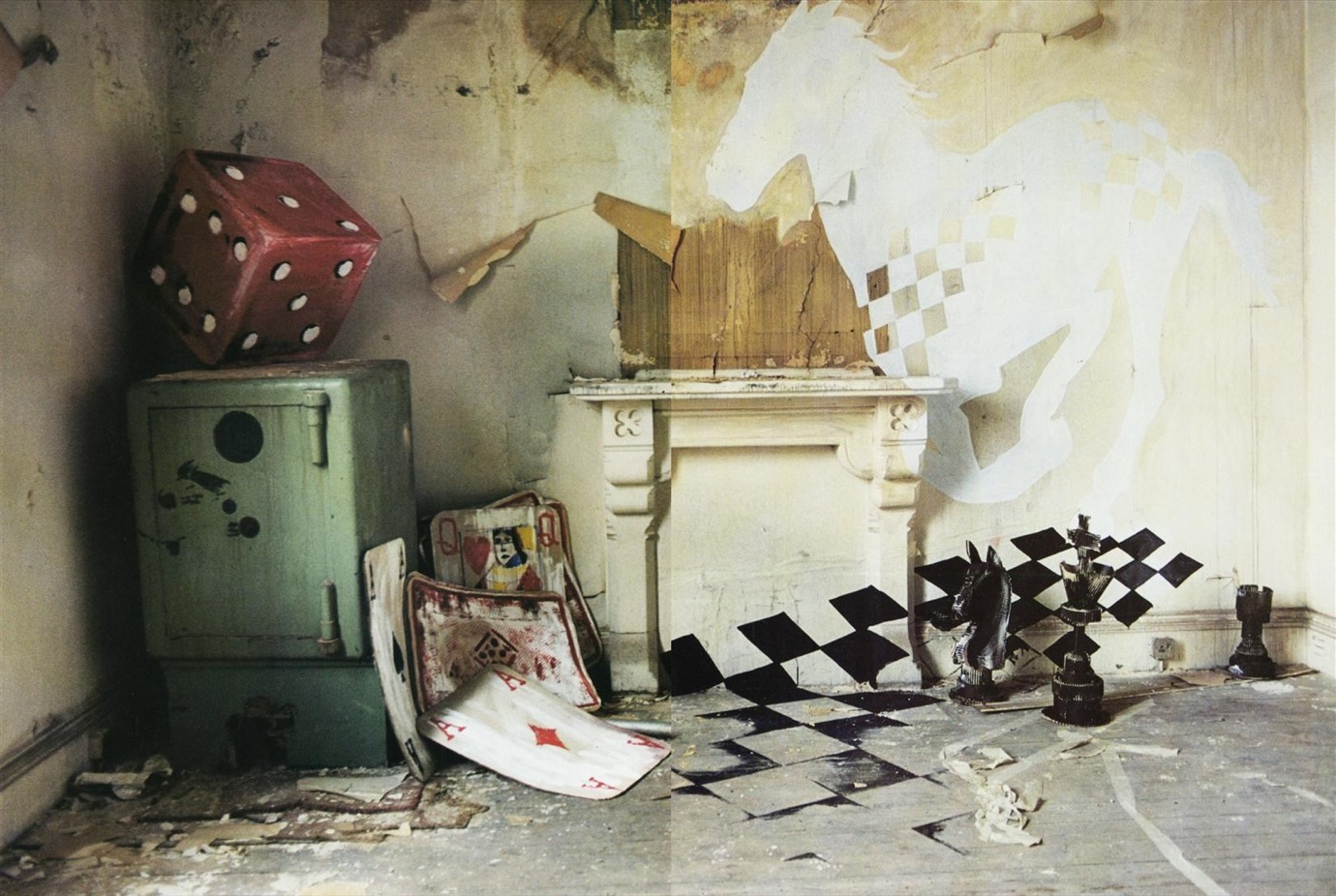

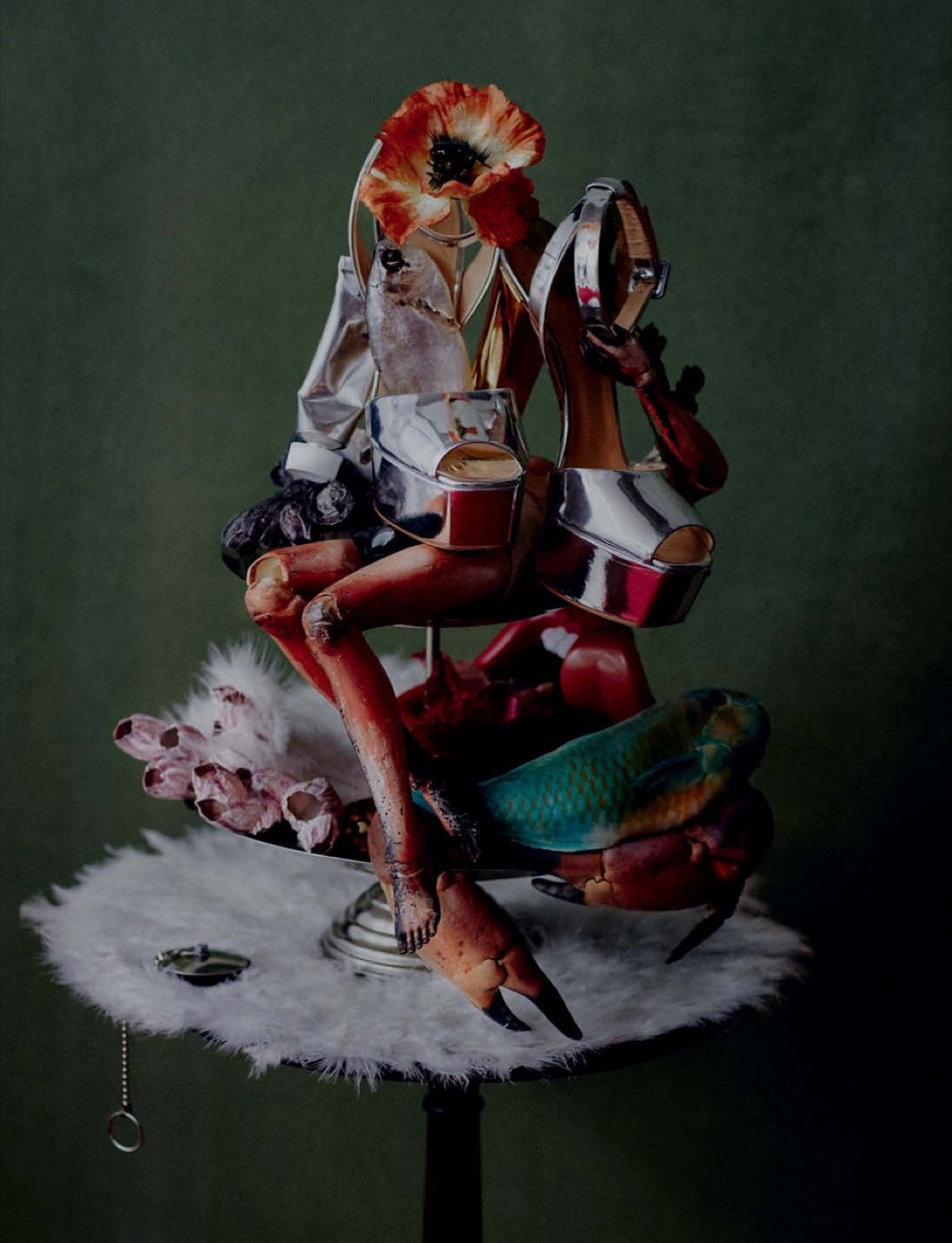

It usually starts with a plan, so they come and say they want an installation with this, this and this. They could be promoting a new perfume or a new handbag. I would normally have an open mind and also prepare three ideas I would like to do. Sometimes they can be quite similar, or very different, and they are not well-formed at this point. It’s so that I’m not stuck already. I find it easier to work on loads of things at once, so I normally do the three designs, show them, and then they pick the one they want. Then I go back and tighten it up, making adjustments based on their responses, and present the next bit. Then I get down to researching materials, talking to the set builders, and visiting the site – that’s always very important. People might send you these pictures of amazing windows or a location you are going to go shoot at, and you go there and it’s such a different experience from what the pictures are. Then I do some sketches and really make it. The making is really the longest part, and I spend a lot of time with the set builders. I don’t really design it as a drawing and say: “Here you go, can you make it?” I go having in mind what I want to make. When we start building, I make sure I’m there during the process, because quite often that is when I see something I like better than what I wanted. Quite often I stop the process and change it a bit during the making. I love the materials and the mess, the scale of it and the actual working on it.

In the beginning (with the three ideas) I normally make mood boards with pictures from artists, from myself, other projects, paintings or references from old Vogues. A real mishmash of different things. Sometimes the things you want to do don’t exist yet, and you can’t just moodboard it. It used to be way easier, because I would just turn up and explain myself, but now everyone just expects an amazing PDF that should say everything. That’s the part that I lament a bit. It used to be an open bit where that person would say: “Oh I love this sketch, I want to do this”, and they don’t really understand what you are talking about. I think that’s a really good thing. They can’t quite imagine what you are going to do. Now it feels like you can Photoshop it up to make it, probably even better than you could [in real life]. I think there’s a discrepancy there that I don’t like. I kind of realized this five years ago and I’ve tried my hardest to sort of rein it back in and sketch rather than use a computer – leaving things a bit more open. I don’t know whether that’s working, because I’m older and people trust me a bit more. They see the quality and caliber of work that I do, so I don’t have to prove so much. But I think it must be really difficult for younger people coming up, they want really every centimeter of material described and represented.