That reminds me of Cristobal Balenciaga’s design process and dedication to obeying the wants of the fabric.

Absolutely. And everything was done in reverse before I met this guy. The fabric choice was always last. Now, I can’t understand how designers can do that, having a certain idea in mind and then going out to find the material for it, that is. Unless you own a mill and can actually make it happen, you’re never going to be able to just find the fabric you have in your mind. Now it’s always about the material first. My grandad was a carpenter, and in carpentry, you always select the wood first. It’s a similar situation when producing music as well.

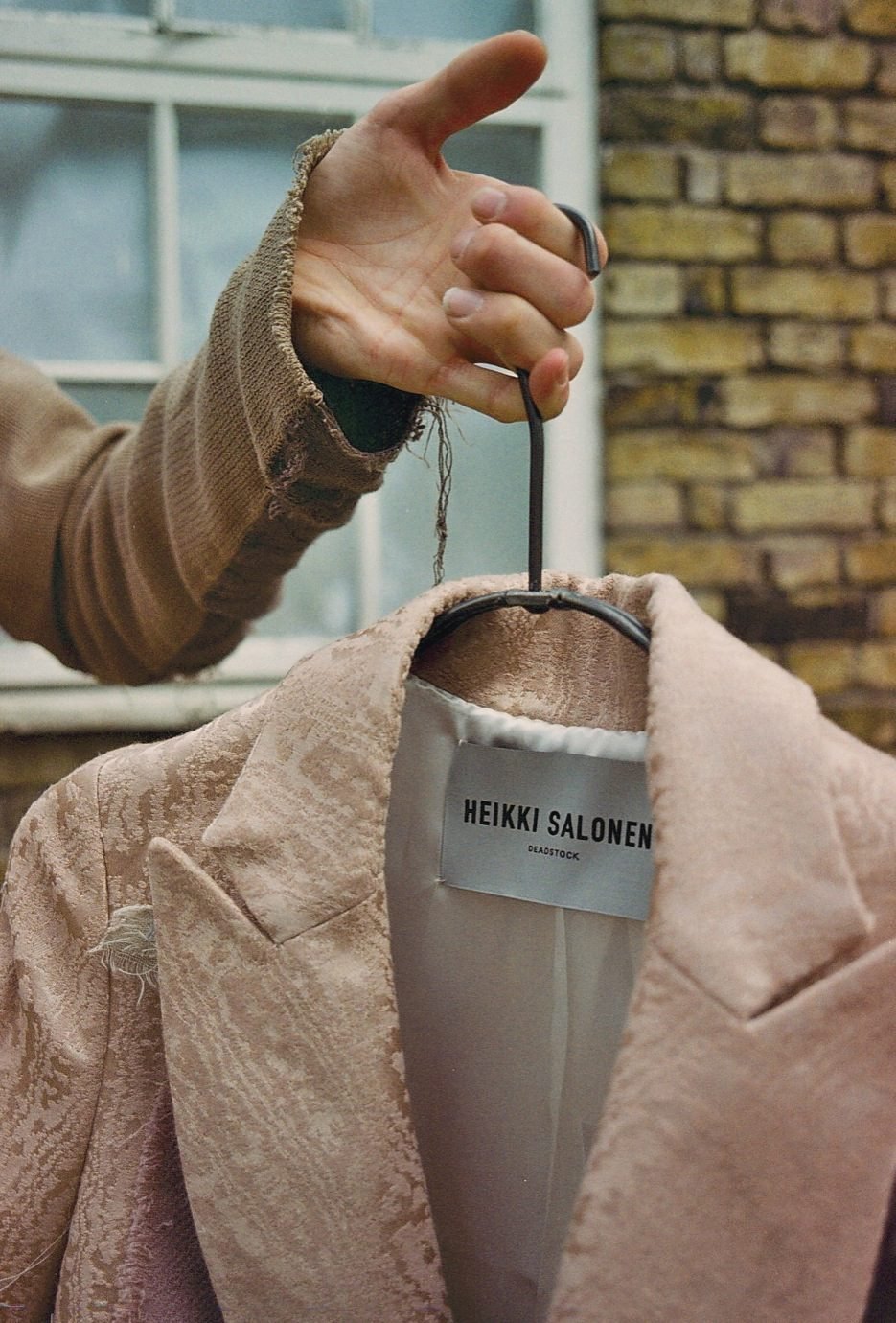

Since you’ve mentioned music, I must say that one of the first things that came to mind on hearing ‘Deadstock’ was a pun on ‘Woodstock’. Looking at the collection, this seems to manifest itself in the patches tacked on to jackets and trousers, almost like band patches.

Completely, and also the materials refer back to old Heikki collections; if you’re aware of them, you know that this patch is from this season, that one from another. They refer back to collections as if they were, just that, bands.

The story it tells is important, but I never want its presence to be too obvious in the actual clothing, it’s a bit too much for the wearer. I want there to be keys of interpretation that they can pick up on, but that they can also apply their own personal meanings to. If they know that this patch is from a certain collection, great, but it could also be that a leopard print patch means something particular to them.

The approach you’ve adopted is fundamentally sustainable, but they aren’t credentials that you explicitly promote. Why is that? Has “sustainability” become a dirty word?

Yes, perhaps, but it should also be something so natural that we don’t need to shout about it. It’s 2019, it should be embedded within us to produce sustainably. My research always has something to do with nature, my Scandinavian heritage, and notions of gender neutrality, all of which are somehow bound with sustainable production practices.

Given your work with deadstock fabrics and your referencing of previous collections, it’d be interesting to hear your take on what originality in fashion is. Does something need to be ‘new’ to be original?

Think of a bass drum in techno; there are two types that all producers use, and yet distinctive, original music is constantly being created. There’s a common language, but the contexts in which you hear it make you reflect on possible new meanings and functions. Fashion is always a matter of many things coming together in a host of different contexts. That extends to whole outfits. It’s frankly amazing how different a single outfit can look on different people. I love losing that control, where I no longer dominate the garment and it takes on new life through its wearers.

That sense of different notions coming together in new contexts fuels your SS17 collection. You have point-collar leather jackets and buckles giving a hardened biker’s masculinity, which is then complemented by headscarves and printed references to Tove Jansson, early Finnish feminist Minna Canth, and Emily Davison, the pioneering suffragette.

It all began with Emily Davison. I went to this exhibition documenting the bandana-wearing women of the Hells Angels. I’ve always been a feminist and great admirer of Tove Jansson, one of the great Finnish authors, and of the suffragettes, and noticed the similarity between Emily Davison and Harley Davidson. You wouldn’t put the two together at first glance, but I felt there were some key similarities in their ideals and how they lived their lives.

For that collection, one of the first things I did were all of the lino-cuttings of prints using wood-carving techniques, marrying early 20th century methods with classic Harley Davidson-style motifs. It was time consuming to say the least, I worked on about one a day.

That’s another thing I noticed in this collection, how you employ certain techniques to pull these references together. The use of visibly rough stitching is a good example. It draws attention to the act of hand sewing and its importance across history in the creation of radical identities through clothing: punks sewed; suffragettes sewed; bikers sewed.

Yes, I think that’s a very valid point. I’m also a great admirer of Japanese boro stitching and the techniques employed by old English prisoners of war. The same stitch is found across all of these cultures, but its placing and the lines you choose to create through them really has an effect on how you view its cultural positioning: this relates to America, that relates to Japan, for example. Or that’s how they figure in my head.

Anyway, for this collection, I began with these [Heikki shows me through a portfolio of illustrations that serve as the starting points for his collections].

When you begin sketching, do you set out with certain motifs in mind? Or do they arise organically during the sketching process?

Both really. I usually spend a couple of days on each, figuring out the silhouette and trying to understand what can come out of it, to see what garments can be produced. Sometimes it’s quite abstract, more of an artist’s approach, which I hate! I’m not an artist, I’m a designer first and foremost and I love to make products. Looking at my sketches, you can see that the most distinctive features of the collection, like the seam down the front of the sleeve, come pretty early on in the process. I already knew what I wanted to do here, but by repeating through the sketches, the exact shape I wanted it to take became clear. Then it was off to the pattern cutting table!

But funnily enough, I never return to those drawings again. It’s a similar process at the other brand I work for, where I collaborate with Robbie Spencer [Dazed creative director]. It’s great working with him, we both really feel that collections should always refer to the past, while hinting at the next collection. It fosters a sense of respect to your customers as well.

“I see myself as a service provider saying: “This is the product, do whatever you want with it.” If that means the clothes go somewhere I didn’t necessarily expect, that’s all the better.”

Off the back of that, there are some subtle common features across Heikki, Vyner Articles and your other brand. How conscious are you of keeping your work at the three separate? Or, on the contrary, how consciously do you cross-pollinate?

No, there’s no conscious effort, they keep themselves separate enough as it is. With Vyner Articles, I’m actually trying to introduce a bit more of Heikki. This first collection was a new venture for me, the opportunity to produce a new sort of collection. But, after the first collection already, its visual language is independent enough for me to easily introduce elements of Heikki without the risk of it becoming a Heikki collection all of a sudden.

Vyner Articles’s name is taken from the street on which your studio sits, known for its community of artists. Is the brand directly influenced by life on the street it calls home?

100%! In fact, when I was studying at RCA, I used to live two blocks away and come here every Thursday for different gallery openings. There used to be seven on this one street, one of which was owned by our current landlord. It was so important to me to be here on this very street; the space matters a lot.

How would you describe the project of Vyner Articles, especially when placed next to Heikki Salonen?

There’s nothing particular that I’m trying to say, as such, it’s more a case of allowing people to speak through the brand. I see myself as a service provider saying: “This is the product, do whatever you want with it.” If that means the clothes go somewhere I didn’t necessarily expect, that’s all the better. Anna Pesonen, for example, she owns perhaps 100 Heikki pieces, and will always ring me up to ask if it’s ok to chop the hem off, or something like that. “Go ahead, it’ll look fantastic!”, I say, so she now has an amazing collection of self-fashioned Heikki shift dresses. She’s a fashion person, of course, but I’d love to see a chef, an artist or anyone else doing similarly. Vyner Articles should be even more open to that.

“It could even be the way someone walks that flips a piece from something that appears aggressive to the total opposite.”

Vyner Articles draws heavily on archetypical workwear silhouettes, but there’s still a sense of tapping into rebellious youth cultures; skateboarding features prominently, for example.

Of course, but this collection was also the laying of a foundation for the brand. We call it “ArtWorkWear”, a collection that treads the boundaries of artwork and workwear. Whether you produce art in it, or turn the clothes into the art itself, the doors are very much open to the wearer’s own creativity.

But I began this collection with sketches of figures that are known for the strength of their personal style. When you think of Peter Saville, for example, you see him in a turtleneck and white jeans, or Basquiat is always in a tailored suit. He completely recontextualised the suit; without him, it would be really hard for me to understand it in the same way.

Looking at them helped me to understand what the collection needs if we’re looking to create a wardrobe for today’s creative. There needs to be a turtleneck, there needs to be a suit, a pant or jacket at the very least.

This research also made me realise the importance of colour to Vyner Articles. I’d never been much of a person for colour, but it really makes sense to focus on it when producing these stripped back, almost stereotypical, garments. What colours do they need to be in order to look new? I mean, look at Basquiat wearing a red t-shirt underneath a blazer, that’s what made it new. Of course, everything is offered in white or black, we’re catering to artists after all, but then we produce pieces in colours that are odd somehow, sorbet tones you wouldn’t be able to find from Levi’s or Carhartt, for example. It triggers something in you, you recognise the shape, just not in that particular colour.