During his MA at the Royal College of Art Salonen worked for Erdem, and after graduating in 2008 won the Diesel Award at ITS #SEVEN. It catapulted him from an internship at Diesel into a consulting job for both the men’s, women’s, and Diesel Black Gold lines – whilst also showing his own collections with Fashion East. But when Diesel started to call him in more and more, and weeks there turned into months, he paused his own label to focus fully on his duties at Diesel, which soon enough turned into Salonen overseeing their womenswear.

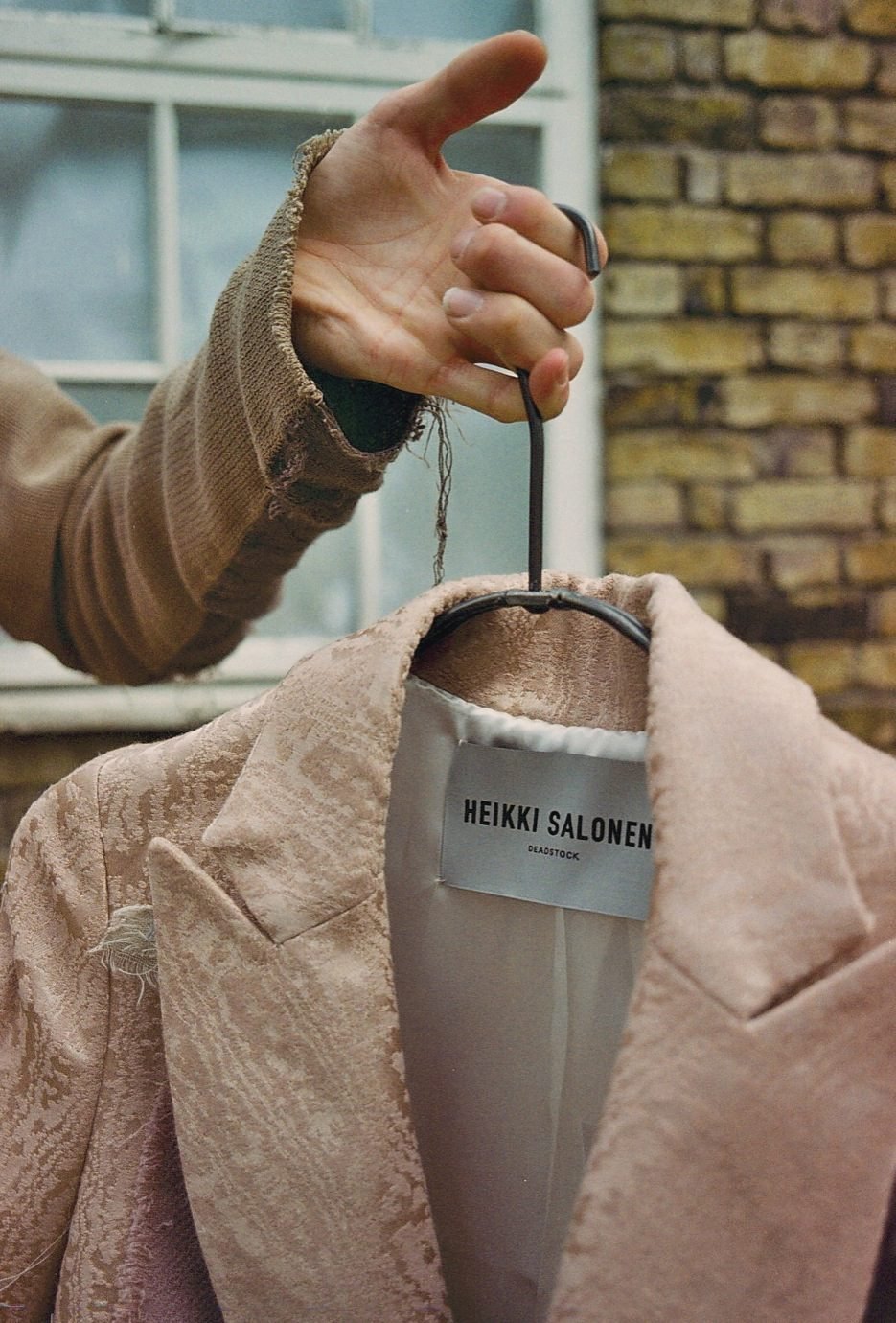

It’s a cold Autumn Friday and Frieze London is coming to an end. While designer and artist Alice Waese is completing ‘The Big Drawing’ on Hostem’s top floor, Heikki Salonen is having a sort of garage sale a few doors down the road. This is in fact the relaunch of his eponymous brand, which, after being on hold for four years, has returned with an exclusive first collection for Hostem: Deadstock. We meet the Finnish designer in his four-day set up on 71 Redchurch Street to talk fashion in 2003, collecting fabrics from the bin of an Italian mill and, of course, Deadstock.

“I THINK A LOT OF FASHION NOW IS JUST NOT CONNECTED TO REALITY, AND I LOVE THE DREAM, BUT I THINK IT’S BEST WHEN THERE’S STILL A THIN LINE CONNECTING THE DREAM TO THE REALITY.”

How was it to design for a brand that is significantly different from everything he’d done before?

“Erdem was in a way more familiar, closer to what I had done – I could connect to the luxurious woman there. Diesel was very different, especially the woman portrayed there, which really drove me forward to reinvent myself. You know, in the jeans world women are often seen from the perspective of men instead of being empowered by the clothes, so I wanted to challenge that.”

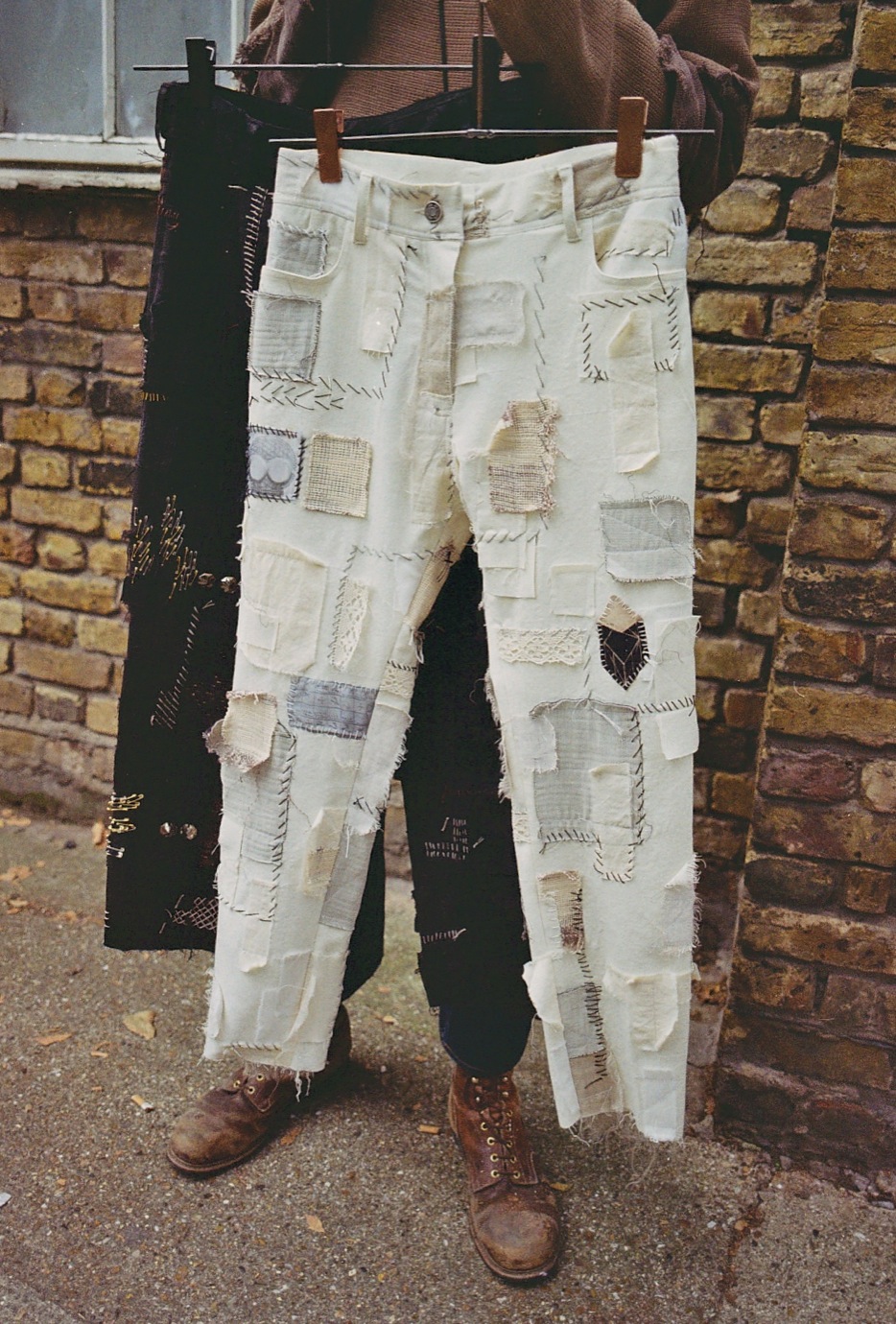

Two years ago Salonen traded his position at Diesel for a new one as design director for another fashion house within Renzo Rosso’s Only The Brave group. He cites 2003 as a year that inspires him to this day: Helmut was still at Helmut and The Face and DUTCH magazine were going strong, though not for much longer. “The youth culture, the nightlife, the music… If you look at those magazines that’s just it for me, and I don’t mean that in a nostalgic way. I think a lot of fashion now is just not connected to reality, and I love the dream, but I think it’s best when there’s still a thin line connecting the dream to the reality.” The influence of music and youth culture comes as no surprise looking at Deadstock, which in some way feels like a group of teen punks cut up and patched back together their families’ most treasured garments.

Hostem and Salonen decided on relaunching his brand together this summer, and a little under two months later Deadstock was born – alongside show preparations for his other job and moving from Paris and Helsinki to London. “And we literally set up the space here in three days. It’s been a rollercoaster… Quite the start for an Autumn!”

“I KIND OF LIKE THE IDEA OF GOING THROUGH THE BINS.”

How has it been launching Deadstock in collaboration with Hostem?

“When I still lived over here it was one of my favourite shops. I really like the atmosphere here – it’s kind of like a family business. And funnily enough two old friends of mine are working here now and they have been involved with Deadstock. That’s how I want to keep what I’m doing now as well: as a sort of friends-doing-something-together-thing. Something quite focused, quite intimate in a way.”

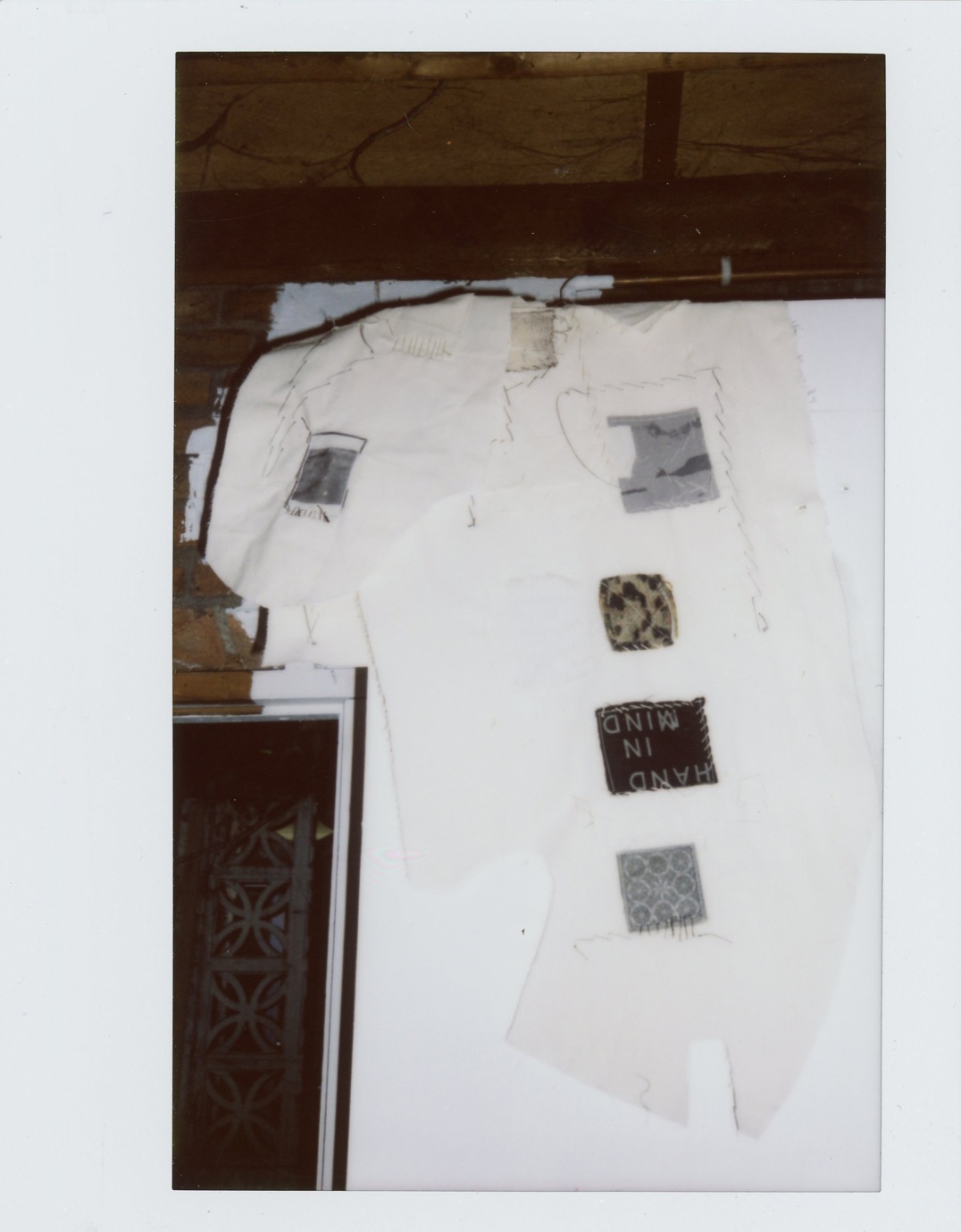

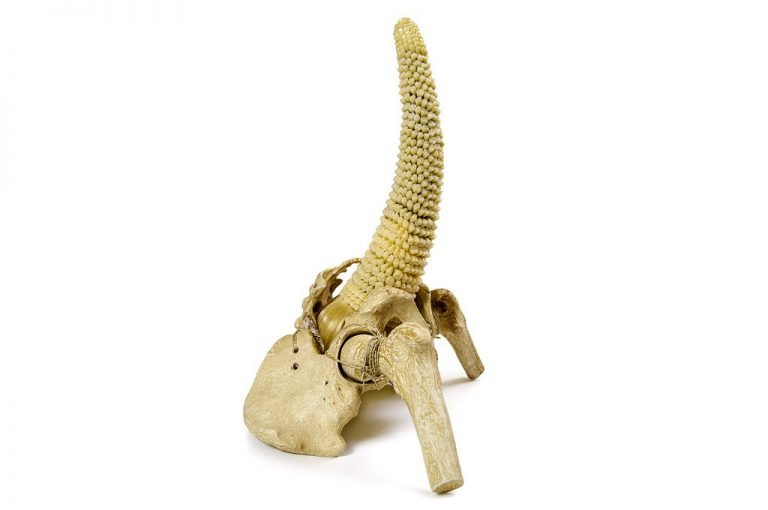

Deadstock’s menswear and womenswear are virtually indistinguishable apart from the necessary differences in cut for coats and trousers. The collection is based on Salonen’s dead stock: fabrics, shapes, and details are taken from his pre-2012 collections and are reworked with the fresh perspective he’s gained in the past few years. Pink silk comes from one collection, leopard print from another, and see-through patches based on old show invites from yet another season. Some of the materials are over 100 years old: silks come from 19th century Swedish scarves, there is hand-printed 1920s cotton (“It’s amazing, even the selvage is printed! You can’t do that anymore, but back then the wood blocks went over the edge.”), and French workwear and maid’s uniforms are cut up into patches. They’re all re-patched together in a beautiful, sort of Japanese boro way, inspired by his many trips to Japan with Diesel’s Renzo Rosso. “There are lots of Japanese influences that I didn’t have before, ‘cause I’d never gone to Japan before. And now that I’ve been there I’ve fallen in love. I’ve been there maybe 10 times now and it’s something that’s really dear to me.”

Why the revisitations, just ‘cause you wanted to use what you still had?

“Yeah, exactly. And referring to 2003 again, what was so great about then was that you could recognise the brands. They were based on classics: you just knew the Helmut Lang fit. And then you get the same shirt again, and again, and again with an attitude that is relevant to the time. I think that’s exactly what I wanted to do with this as well: to make something that is relevant today. I would also hate to see these beautiful pieces go to waste. There always will be a few dead stock pieces to go alongside the rest. There’s also something sustainable about it.”

Without defining it just with that word…

“Yeah, that’s why we called it Deadstock and not ‘sustainable, recycled old pieces’. The name is quite brutal, and a bit misleading at the same time, but I kind of like that. It’s nice to confuse. And it has that type of little subcultural connotation to Woodstock.”

“THE PRODUCTION IS ALWAYS THE TRICKY PART. YOU SHOULDN’T BE TOO SCARED OF IT, BUT I THINK YOU DO NEED TO ACKNOWLEDGE IT.”

But the idea of using dead stock goes even deeper. For the past few years Salonen has been helped out by the Bonotto fabric mill in Molvena, Italy. “We hooked up together ‘cause I was going through his bins when I was in Diesel – the factory was just next to this mill. Every day when I was walking back home from the Diesel Creative Centre I’d go through all the scrap material in his bins.” The Diesel studio manager put him in touch with Giovanni Bonotto, the Creative Director of the mill, who has helped him out with fabrics ever since. “I kind of like the idea of going through the bins. I still have loads of those fabrics left. They are beautiful – most of them are trials of different colours, so they are all unique pieces of material.”

Are you nervous about restarting your own thing on the side, knowing how tough it can be?

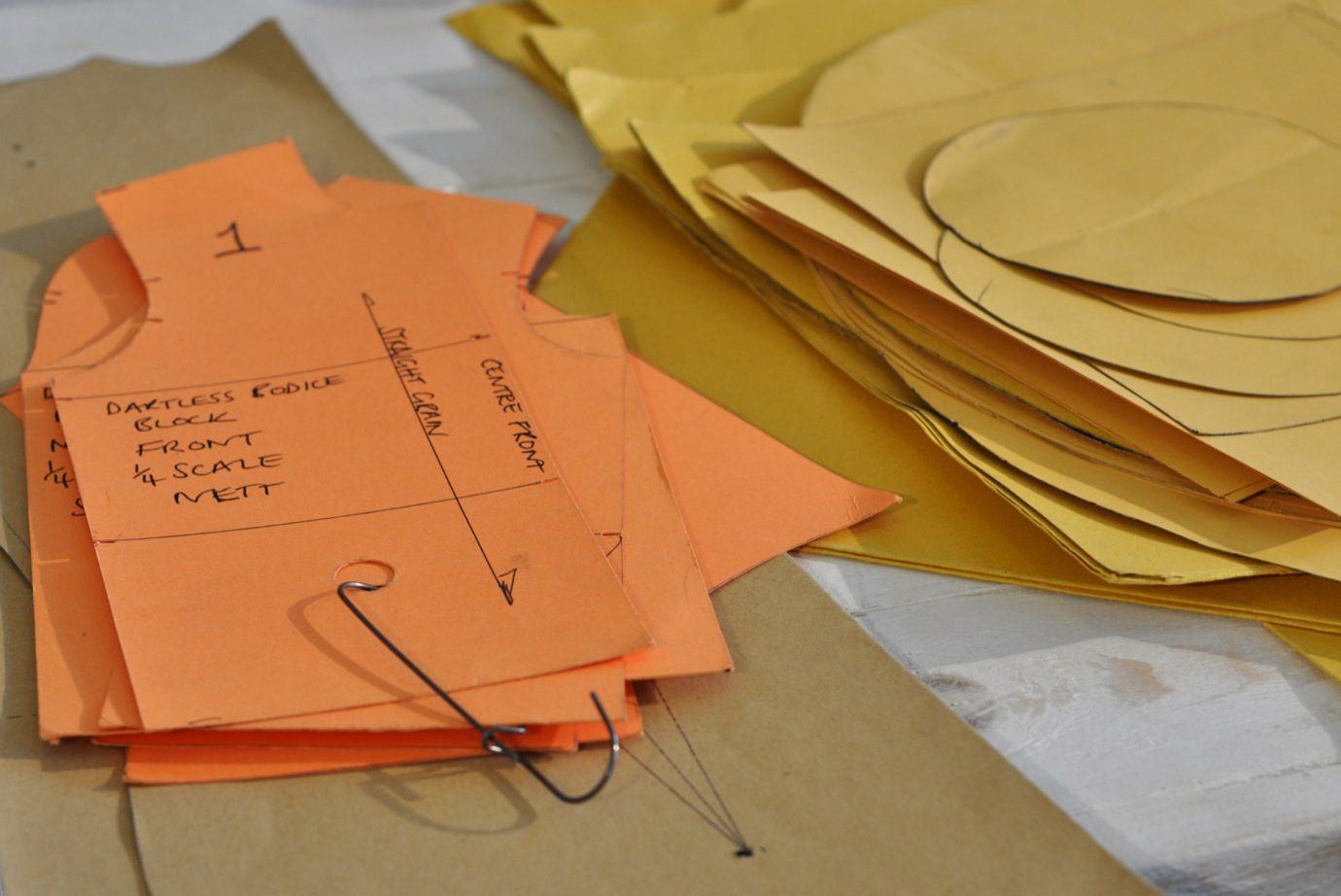

“Of course I’m a bit nervous, but at the same time, even though my current director job is great and fulfils creative freedom to do things that are similar to my own aesthetic, it’s very different to this. With my current role I get to work with a great team to make a bigger amount of products that are within a certain brief. On top of designing it is a lot about delegating the process to the hands of others, whereas Heikki Salonen, even though I work with a team there too, is all about being able to be surrounded by fabrics, toiles, and images myself – working on every single pattern and product with my own hands. They both complement each other and I can’t really live without either of them…” He laughs.

As someone who had both his own brand and a design job at a major company practically straight out of MA, what’s the advice you’d give to students who want to start their own label?

“The production is always the tricky part. You shouldn’t be too scared of it, but I think you do need to acknowledge it. Because being late is the nastiest thing to do. I hate being late and I always say to my team that we can do whatever, but we can’t be late. ‘Cause that kind of ruins it all. Nobody wants a person that’s late. I think that’s the only lesson that I would give to students who are starting their own brand: do things that you can actually manage to do. Do less quantity and focus more on the product and what you really want to present. And be on time – when presenting it and when selling it.”

Despite all the handwork that’s gone into it, and the production that was done in London, on a small scale, Salonen’s done his best to keep the prices accessible with Deadstock – how?

“I get less money, if anything!”

He laughs, but after a few seconds continues in all seriousness.

“It’s fine to do that once or twice, but then I think you have to make it look healthy. And never go minus – that’s not a great choice. I think that’s another lesson.”

So what’s the plan after this?

“To work with nice people, that’s the plan. Whatever I can do with good people, and friendly people, and excited people whose company I enjoy… I think that’s the plan, with everything.”

Heikki Salonen Deadstock is now exclusively available at Hostem