“WHAT IS A FIVE YEAR OLD GIRL SUPPOSED TO THINK WHEN SHE WATCHES CINDERELLA, SEEING GIRLS TEARING APART HER SISTER’S DRESS?”

If you think of any mainstream film production, chances are very slim that it features multiple female characters. And if it does, chances are even slimmer that those women exchange more than two sentences. “The girls don’t talk to each other, there is no dialogue. They talk to the men, but that’s it.” GIRL.IS.A.GUN was initially designed as a university project, but it quickly turned out to be much more than that. Founder Natassa Stamouli created a platform that tackles girl hate with the simplest form: a dialogue.

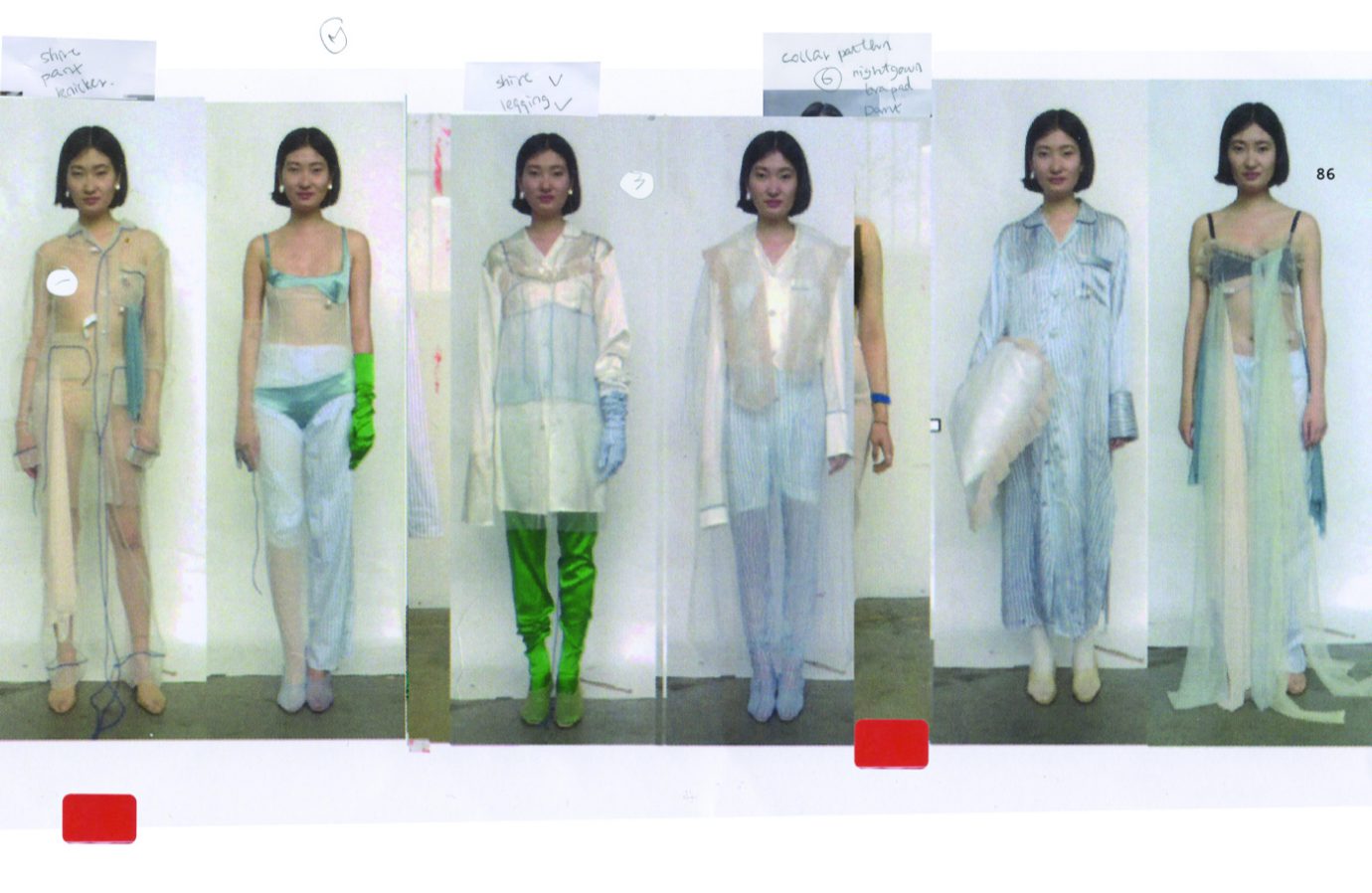

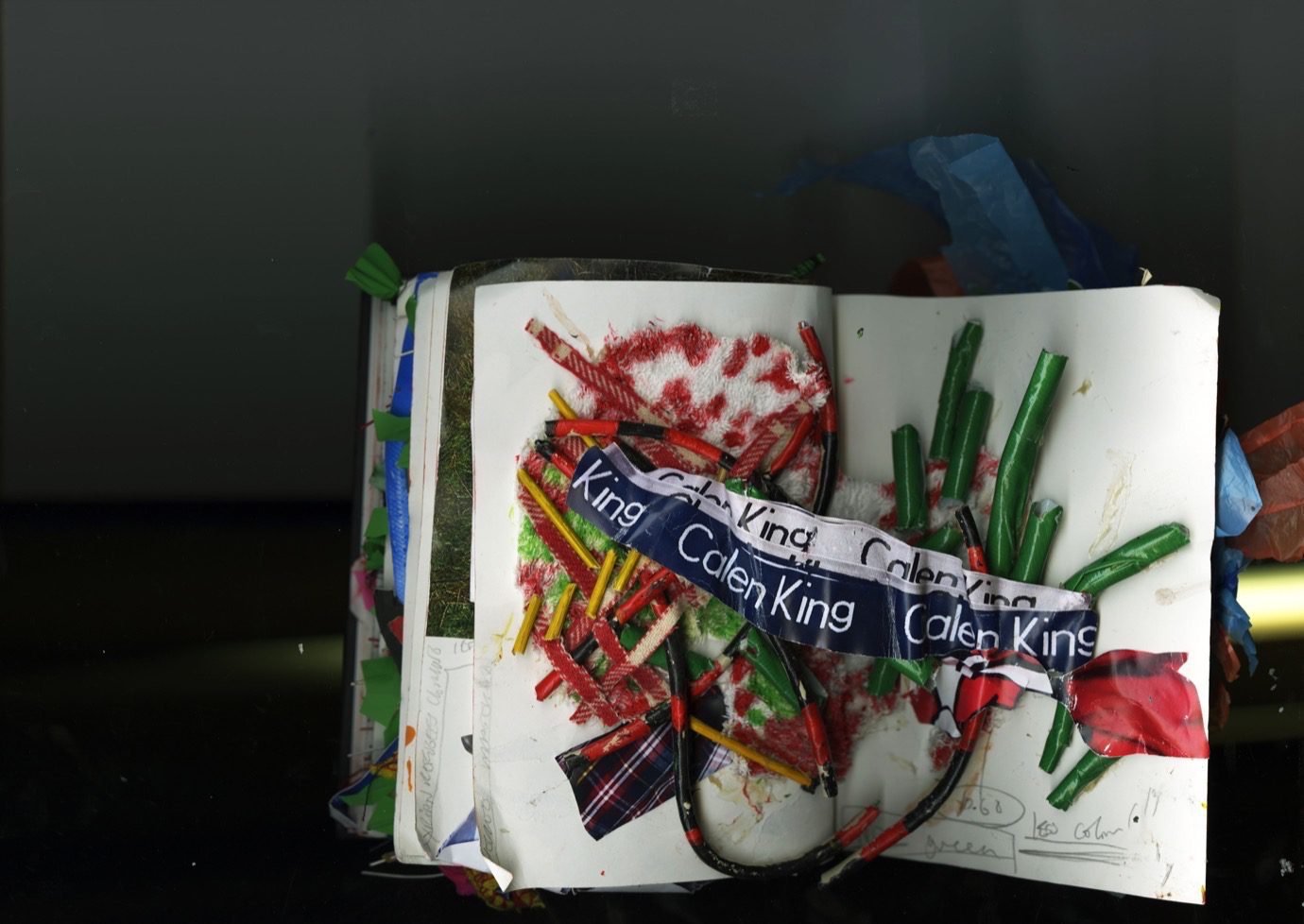

Natassa knows a thing or two about communication and how to manage it – she graduated from Central Saint Martins with an MA in Fashion Communication last year. For her final project, she created the second issue of the magazine, based on the stories of girls from around the world. GIRL.IS.A.GUN is written by girls, for girls and anyone can contribute and join the dialogue. But why launch a magazine about girls in an already oversaturated market, in the times where print is said to be dying?

To Natassa, what was and still is missing, are personal stories from real girls. Open any other magazine and you’ll find the girl boss, the cool kid, the celeb model or the successful designer smiling back at you – empty stereotypes designed to inspire. “They’re either really pretty, or really successful, but I want the girls who aren’t mentioned anywhere,” Natassa wants the magazine to act like a big sister, one that’s always there to listen. A sister that will give girls a voice to share their most intimate stories with an audience that is accepting.

Natassa herself didn’t have a big sister growing up, what she had was sisterhood. Her role models weren’t celebrities, they were her girlfriends. Role models without airbrushed faces, years of life experience or incredible success stories; who struggled regularly and experienced failure.

And that is what sets GIRL.IS.A.GUN apart from other magazines: the founder goes through the same struggles as the audience that is looking for guidance. GIRL.IS.A.GUN isn’t striving for perfection but rather aims to showcase flaw and failure as a way for girls to connect and grow together. Should girls stop comparing themselves to others? Not necessarily. They just aren’t comparing themselves with realistic role models. The covergirls aren’t real.