It is calming to hear that Borsche started out small. After studying graphic design, he began to work in advertising, but soon grew tired of the back-then ego and power-driven industry: “In advertising you are basically editing large corporate manuals, it often doesn’t have much to do with design. That’s why I can’t watch Mad Men, it’s just too dramatically authentic.” His first steps in editorial design, though, were not exactly as he expected: “My first proper design job was Jetzt Magazine, for the first issues I designed, possibly the worst magazine in the world. I was completely overwhelmed, I had no idea how many rules there are in making a magazine, after a few issues I started to understand how a magazine works.” Opening his own studio in 2007, set in a wooden kiosk, eventually allowed Borsche to make his own rules and to develop an idiosyncratic visual signature.

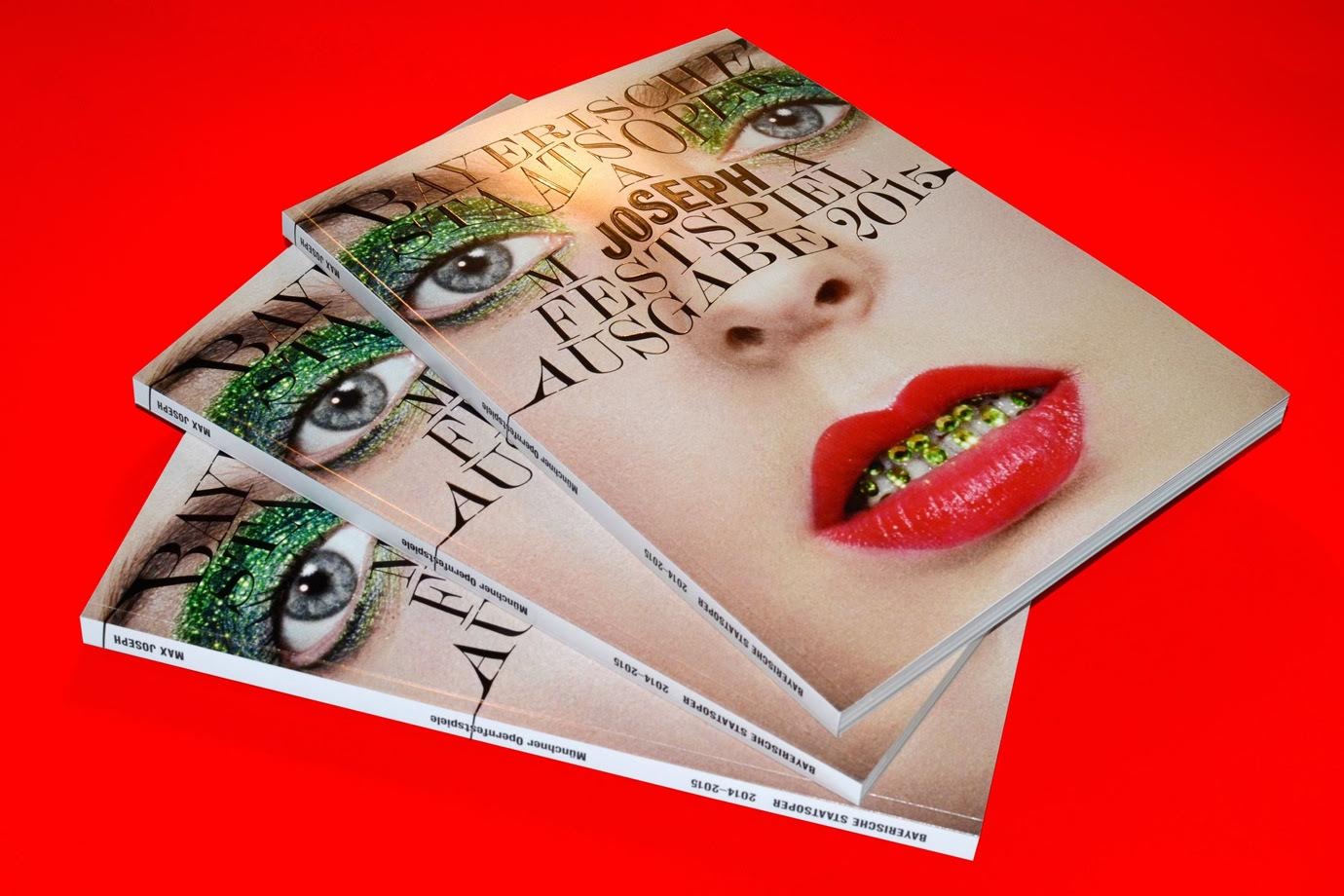

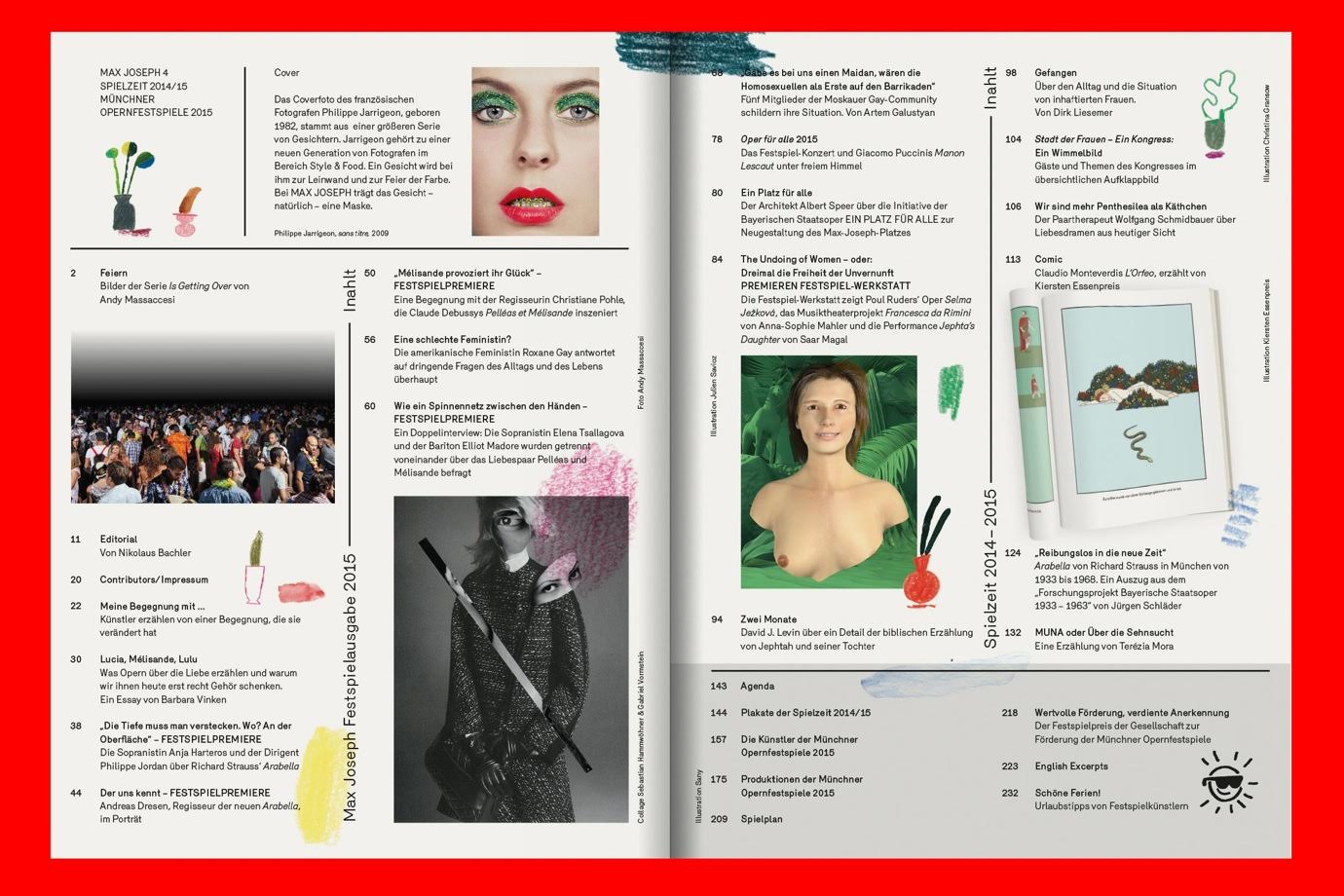

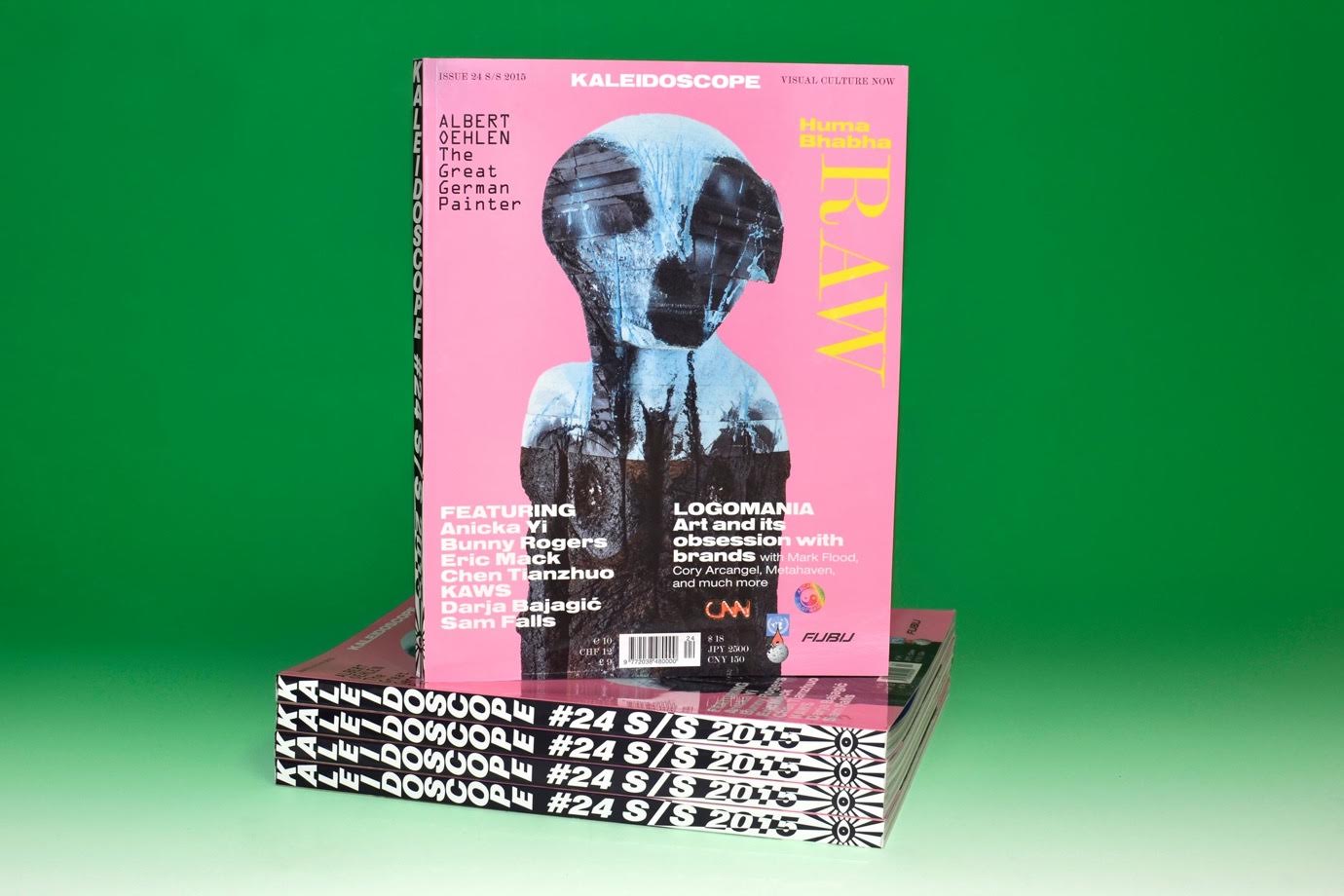

I am not surprised to learn that the father of two learned his craft through graffiti as a teenager. “I liked graffiti because people see it, if they want to or not. If a businessman is going to work by train and there is a panel on it, he has no option but to engage with it.” Today, Borsche is art director of several leading art magazines and the aesthetics of graffiti is still a key influence: “There are enough magazines which present art in a very clean look. Take the beautiful Art Review in London, it’s super polished and looks great.” Borsche is pushing into a different, less White Cube, direction. Instead of letting art speaks for itself, he engages in its visual language, creating a dynamic two-way discourse between content and form: “Spike has almost has a 70s vibe to it and a very fine-tuned layout. In contrast, Kaleidoscope has a bolder and more experimental design, which fits the artists they feature. There is definitely a dialogue between content and design.” Borsche likes to play with the boundaries of design and taste: “The way we use fonts sometimes hurt a bit. We like to experiment. If that means stretching the limits of what we consider beautiful, we can live with that.” Is this richness of styles an anti-position towards German pragmatism and intellectualism? “True, our style is not typically German”, he says, “but boldness is never a goal in itself”. The 43-year old is not trying to provoke. “My best friend’s mum collects the programmes we do for the Bavarian State Opera because she appreciates them as objects, and she has nothing to do with design.” Borsche is aware of the designer’s responsibility towards the public. Appealing to a heterogeneous audience of different ages and interests is therefore much more satisfying for Borsche than to only address a scene of design insiders. “Niche”, he says, “is boring anyway. My only goal is to make good design work.”

“I THINK NICHE IS BORING. I’M NOT INTERESTED IN THAT.”