Where do your raw materials come from?

Viscose mostly comes from Sweden, from a supplier called Domsjö. We use majority organic cotton, and we are trying to get a higher percentage. Our cotton comes from India, Turkey, the U.S., and Greece, and supporting organic cotton in any of those places is extremely important because the difference in soil health between organic and conventional is crucial; the amount of chemicals used in conventional cotton is horrific, especially for the people growing it. We use recycled polyester wherever we can and are engaged in getting plastic out of ecosystems by removing them from oceans, by using recycled water bottles and supporting clean up efforts. Our wool comes from New Zealand primarily, and some of it comes from the UK.

And can you talk a little bit about the dying process?

We’re lucky that almost all of our fabrics come from Italy. The regulations in Europe are stricter than a lot of other places in the world. As part of the Kering group, we have an active plan to ensure the complete removal of anything that could be considered hazardous by 2020. We’re also working with ‘Cradle to Cradle’, which is a closed-loop, circular economy organization. We’ve been working with them a lot on developing safe, biodegradable dyes, by trying to ensure that any of the dyes we use through one of our key suppliers are completely non-hazardous. We want our dyes to be considered biological nutrients so that at the end of their life they can degrade and create healthy soil. Dying chemicals are a significant part, but it’s also about the amount of water and energy that is used. For four years now, we have been a big supporter, advocate, and user of the ‘Clean by Design’ program developed by the NRDC (Natural Resources Defence Council) in the US. It focuses on water and energy reduction.

What are some of the hurdles the design team need to overcome in order to remain sustainable?

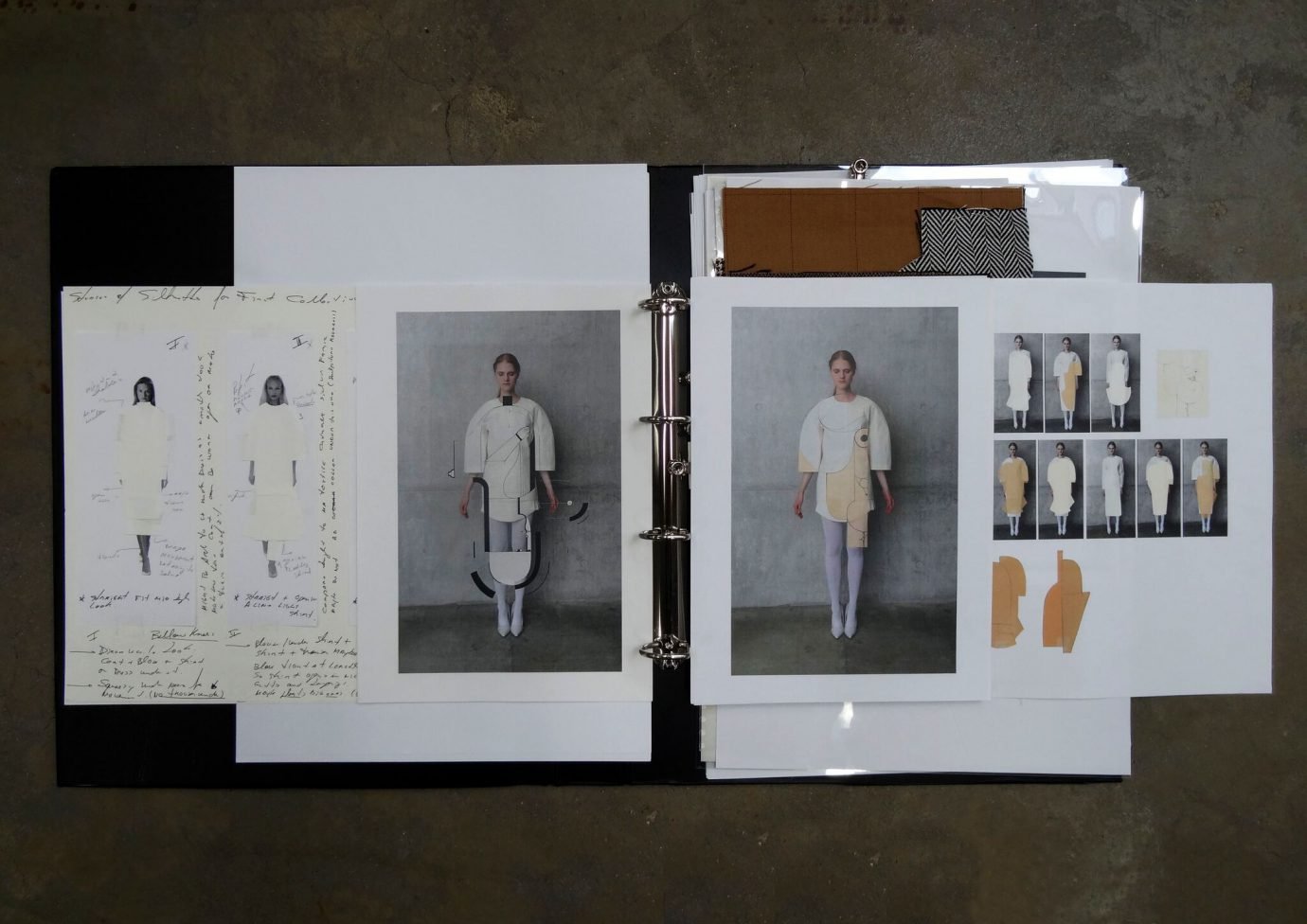

It’s hard. We work very closely to try to find a balance between what we need to do as a business to continue to make progress, and not putting so many constraints on the design team that it wrecks the creative process. It’s a very delicate balance: sometimes we go too far one way, and sometimes we go too far the other way. We are still a design-minded business, and the quality of the design of our product is our number one priority. We also are very conscious of what people consider sustainable fashion. There is a real interest in our company to prove that sustainable fashion doesn’t have to look any different, that it can look just as beautiful, luxurious and exciting as anything else. So it has to be collaboration.

“There is a real interest in our company to prove that sustainable fashion doesn’t have to look any different, that it can look just as beautiful, luxurious and exciting as anything else.”

What are some of the biggest feats that the company has accomplished?

We’ve been really focused on fixing existing supply chains. One of our biggest successes was our work around viscose that we did over the past 3 years. We made a commitment with an NGO (non-governmental organization) called ‘Canopy’ to make sure that none of our forest-based materials, primarily viscose, come from ancient or endangered forests. We were successful in setting up a fully traceable supply chain, where we knew the actual forest, that it was sustainably certified and we also knew that the viscose supplier was chemically responsible because that’s a very significant concern with viscose. Viscose is not an innovative material, but the method in which we’re able to get it and know where it comes from is a huge innovation for us. We’re the only company that has that, anywhere. We’re also focused on new innovation in fibers, but none of them are scaleable or commercially available, yet. We are very committed to supporting those innovators, but it’s still going to be a few years before they’re commercially available. It took us two years to get our viscose supply chain set up. It takes time.

Whether they are looking into starting their own business or working in a business, what do you think is important for students to remember?

That the things that are most removed from us here in our office are where the biggest impacts are, both on humans and on the environment. I always tell people just to meet the people in their supply chain. If you have a fabric supplier or manufacturer that you like, get to know them, figure out what you can achieve together. The people we have contracts with should be as important to us as the people in the main house. When that happens, you almost always bring your own values to them, and you can start building up projects. If you don’t have a huge amount of business power, it’s about finding people who are like-minded, and who want to do exciting things.

Many people can’t afford a sustainable luxury. How can they still shop consciously?

Not everyone is able to afford luxury clothing, but even on the high street, people need to stop treating clothing as disposable. It doesn’t matter about how much something costs, it matters how many times you wear it.