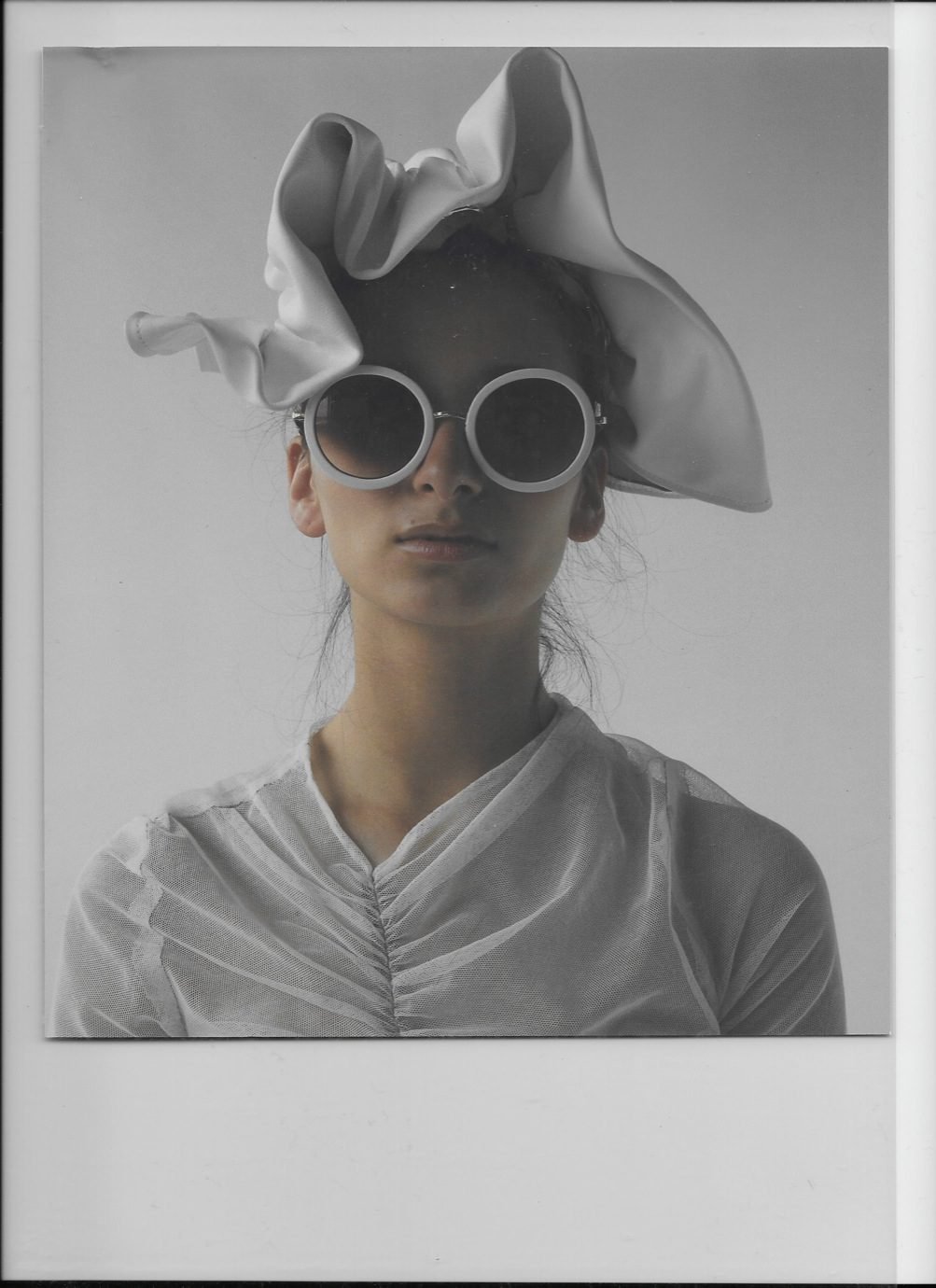

The clothes the designer makes faintly call images from medieval European folktales to mind, ones in which apron-wearing women work the fields with handkerchiefs tied over their heads. It’s an image that some would baulk at today, dismissed as a hangover from a harmful yesteryear. Removed from its socio-historical context, however, Chloé sees something of an almost emancipatory ilk. “It predates the idea of mixed garments, which we only begin to see with the advent of women’s emancipation movements and the adoption of menswear clothing as their own—on both sociological and ergonomic grounds. You could almost think of it as a sort of vintage sportswear,” she suggests, a claim that might leave you scratching your head as you try to match the image of a dairymaid to the skin-cladding tech-y silhouettes we more readily associate with sportswear today. But, on deeper reflection, she has a point. “Ultimately, what was worn in that particular period retains an idea of movement, made with the purposes of physical work in mind—it’s workwear that has yet to come under the influence of menswear.”

“Coming back to school, having interned in the industry before CSM, was quite hard in some respects. I had a bit of an existential crisis, wondering ‘What are we doing here? There are people my age with their own brands, making real garments!’ I think that fed into my work and made me focus on being really neat.”