What is it that you’re making?

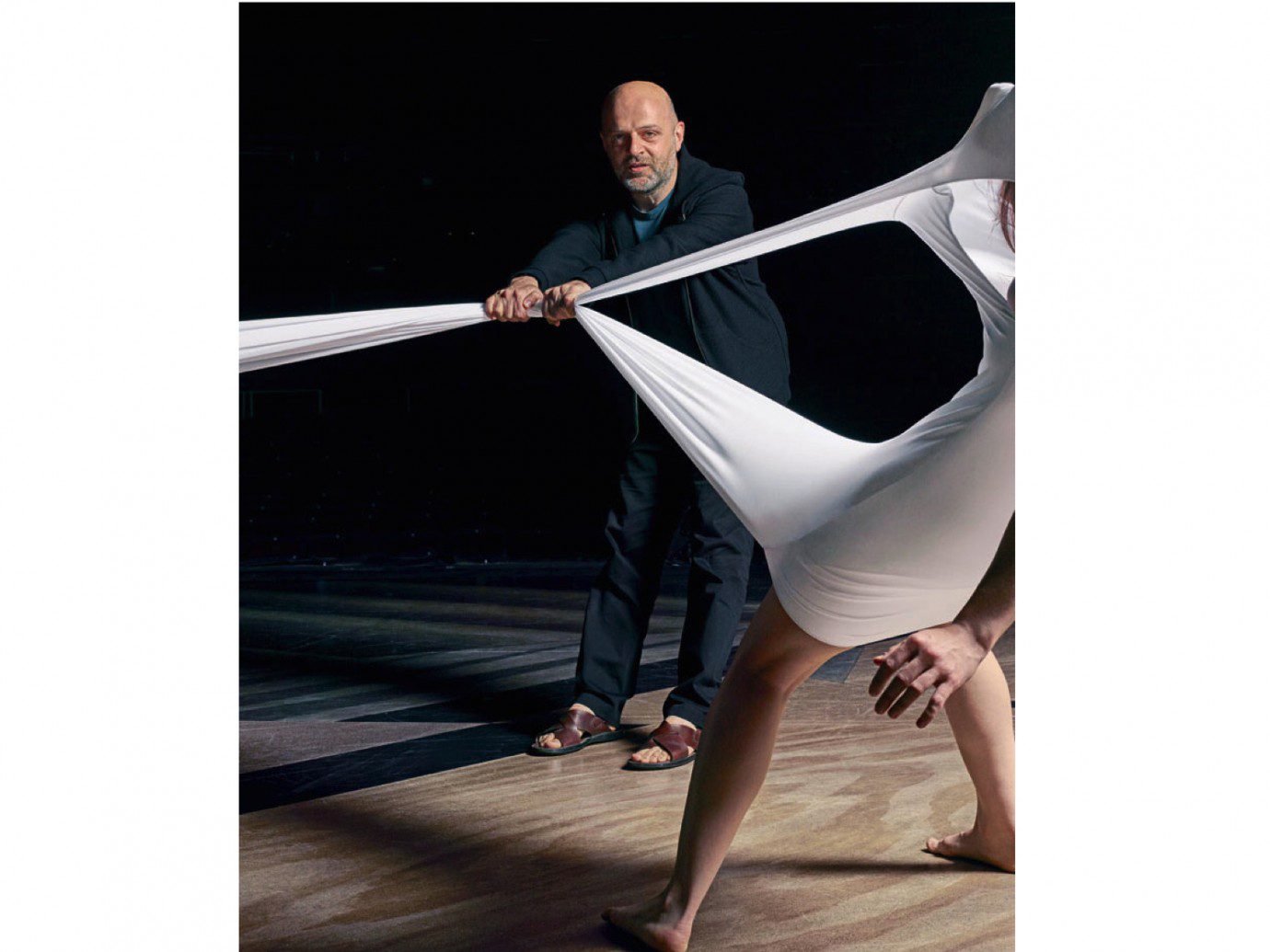

I’m making a performative experience – something that is alive and something that moves. I make work that’s alive and has breath in it. Sometimes it’s just myself and other times I work with dancers and movement artists. I am interested in the moment. What’s happening on stage is influenced by what’s going on psychically for me when I make the work.

Having just graduated from your MA in Performance Design and Practice at Central Saint Martins, do you feel the course was helpful for you?

Yes. Absolutely. Prior to going to Central Saint Martins I had not really collaborated, with anyone. I’d worked with people but that’s different from collaborating. Being able to collaborate is being able to share ideas and make something together rather than tell people what to do. The biggest lesson I learnt from collaborating at CSM was that sometimes you have to let your ideas go. You may think your idea is the best but, as a collective, if everyone decides it’s not working: let it go. For me that was a very humbling experience because at times as artists we can become attached to our own ego(s). I had difficulties with my classmates because I come from a place of doing. Let’s not talk about it, let’s do it. The majority of my classmates came from a place of talking about work. And I had a problem with that. I don’t really want to talk about anything. Can we just try it and then, if it doesn’t work let’s try something else. I was constantly butting heads and that, for me, was challenging. I’m an assertive person but I’m not interested in conflict. When I was not able to choose the people I collaborated with I was not proud of the work. It was only when I was able to choose my collaborators that I would feel that we were all coming from a place of respect.

“THE BIGGEST LESSON I LEARNT FROM COLLABORATING AT CSM WAS THAT SOMETIMES YOU HAVE TO LET YOUR IDEAS GO.”

What would be the ideal space for the presentation of your work?

At the fucking Barbican. I saw Trajal Harrell, he’s an artist from New York, at the Barbican. It was a performance-based exhibition. His performance was great. I was inspired by his work. The space was fantastic, the levels. The idea of doing durational work… I’m interested in using multiple medias, to tell a story. I’m not interested in a frontal experience. You know, maybe a video behind; maybe some clothes; maybe a mannequin with a particular outfit; maybe some text… I am interested in the best way to tell a story. If the story is best sung, let’s sing it. If the story is best danced, let’s dance it. If the story is best shown on a video, let’s show it on a video.

When is the work happening?

The work has already happened. My intention is not to make something new. My intention is to make something that I know. I take the past and I bring it into the present. Hence, I do a lot of autobiographical work. It’s the idea that drives the whole thing. For me the idea is the meat. The performance is just the rice and salad.

“FOR ME THE IDEA IS THE MEAT. THE PERFORMANCE IS JUST THE RICE AND SALAD.”

What excites you in your daily life?

I’ve started gardening with a group of old ladies in Richmond. It is fantastic! I have exhilarating conversations with these women who are completely different from me. When I’m gardening I’m thinking about what I’m going to make next or, what am I going to do in San Francisco at my upcoming residency. Gardening gives me that space to think about the trajectory of my life and where I want to go without it being an anxiety-driven task. I started gardening because I was listening to Women’s Hour and they were saying that it is a way of improving your wellbeing so I thought, I’ll do it.