“DID THEY USE MAGNETS, ROBOTS OR PUPPET STRINGS?”

When the lights illuminated and the red velvet curtains descended, I caught up with a couple of BA students at Central Saint Martins, who had plenty to say:

BA Criticism, Communication and Curation student: “I felt the clothes became limits to the movements. The dancers’ bodies were confined and the whole production seemed more like a development of his research for fashion rather than a mature dance performance.”

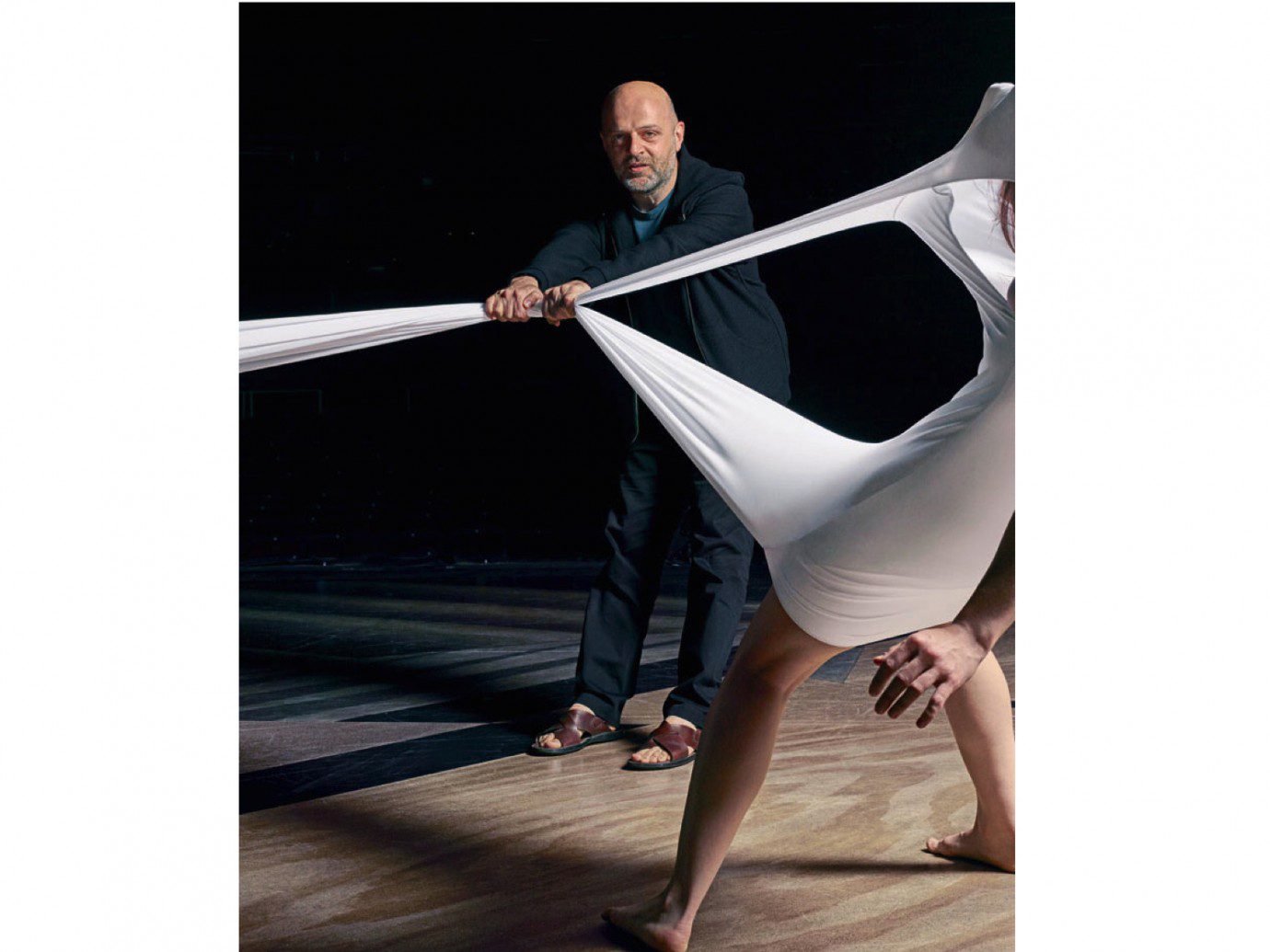

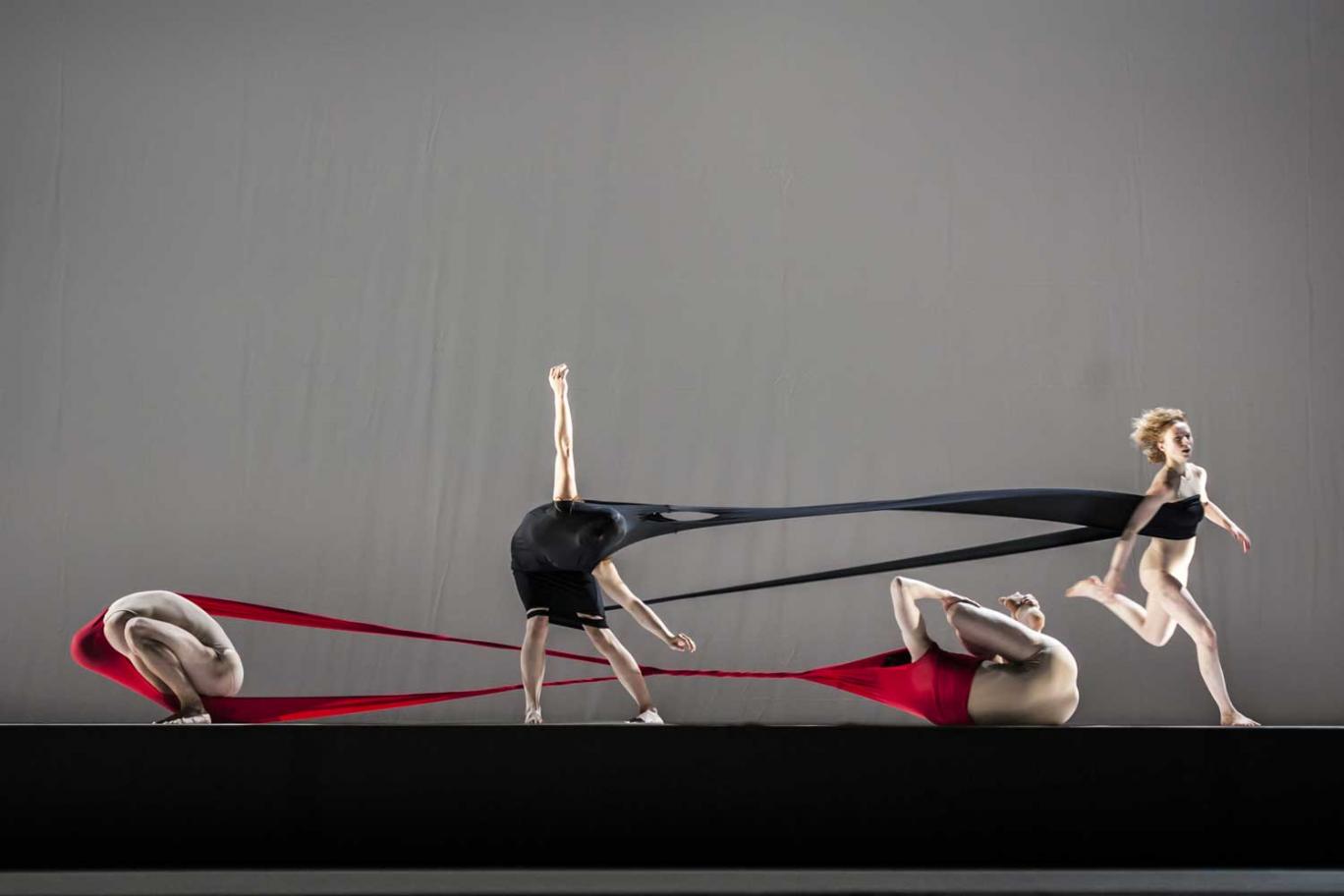

BA Fashion Design and Marketing graduate: “I really enjoyed Hussein Chalayan’s Gravity Fatigue. I thought the short dance pieces worked well and spent a lot of time afterwards trying to figure out how the dancers and their clothing preformed in particular ways. Did they use magnets, robots or puppet strings? I don’t think the dancing or clothing would have been so interesting without the other. It made an ideal partnership that combined movement, colour, shape and sound. At one point, as the dancers were stamping, spinning and bouncing their bodies off the floor, I was so mesmerised in a trance that I practically fell asleep!”

“Frustratingly episodic” in the Financial Times, “daft but visually arresting” in the Telegraph and “too skittish to really work” in the Evening Standard – there were similar scathing reviews by dance critics across most newspapers in the days following the show. They were right to a certain extent. The stop-start sequences teased with titillating ideas, but when they were not fleshed out, they were merely appetisers that left the audience in the lurch and hungry for more. While the production could have been a meatier offering with fewer but fully formed pieces, it was inevitable that it would come under scrutiny. After all, fashion has transcended the esoteric bubble and seeped into mainstream culture and entertainment in recent years so it would be understandable that dance, one could argue sits higher in the hierarchy of the arts, would deem undeserving an endeavour by a fashion designer, even one as concept and performance driven as Chalayan.

On the other hand, there were positive appraisals from perspectives within fashion. Students and professionals I spoke to felt that the performance demonstrated the creative possibilities of collaborative projects within the arts. With an unforgiving industry that demands six collections a year at a rate of one every six weeks, it was a triumphant feat of time management for Chalayan to even consider such a project outside of his relentless workload this year – he opened a new store in London’s Mayfair district in September and presented a well-received collection of dissolving dressesin October in Paris.

All issues considered, everyone I spoke to agreed on one thing; Chalayan’s cross-pollination across fashion and dance was a win-win all around, a new money and audience for dance and Sadler’s Wells Theatre as well as a novel appreciation of fashion and the possibilities of clothing for an ailing industry.