Kaat studied literature and philosophy, and ended up doing a PhD after her master’s degree; working on contemporary dance within a department of theatre studies. After two years, she quit, as she realised that pure research was not her cup of tea. “It was a bit too lonely for me,” she says. “I do research within my job, but enjoy it when it’s not my only focus.”

Even though Kaat was not formally trained in fashion, she ended up applying for the position of fashion curator just before the MoMu opened in the early 00’s. Linda Loppa — who was the director of Antwerp’s Fashion Department at the time and had a vast experience in both design and running stores — was one of its co-founders, and directed the museum. “We were a perfect match, as we were two inexperienced people, but still had a good knowledge. We were experimenting with the fashion museum, trying to find advantages and disadvantages, and had the freedom to do it in our own way. The hardest thing is to display fashion, because clothes must be worn. It’s really hard to maintain dynamics and energy in an exhibition. Also I think that the digital world opens up many opportunities for fashion to be transmitted,” she says, as we roll into the conversation.

“THERE’S NO HANDBOOK OF HOW TO COLLECT. SOMEHOW YOU TRY TO MAINTAIN OBJECTIVE CRITERIA TO DECIDE WHY A LOOK IS INTERESTING OR RELEVANT.”

The fashion industry has accelerated in the past few years— do you notice this change while working in a museum?

Museums, in their essence, work with a completely different rhythm than the fashion world, but I think that’s also the luxury that museums have. I think one of our main tasks is to offer a place for reflection and analysis, and to offer people a space where they can take time to look at a garment and discover the story behind it.

Making exhibitions is one thing, showing objects is another thing, and now you have — since about 15-20 years — the emergence of fashion film, which is a completely new medium. How do you approach that as a museum? How do you integrate that within your projects? Another challenge is how to collect fashion: when you look at our historic collection, it’s more of a reflection of how people dressed in Antwerp in the 18th or 19th century. It’s different when you look at our contemporary collection: it’s not a reflection of how people are dressed nowadays, because fashion changed drastically. There are different segments: we have haute couture, pret-a-porter since the 70s, and high street fashion. How to collect all the different types of fashion? We, as a museum, made a very conscious choice to collect designer fashion. It’s a choice that limits us, because in a hundred years time, someone won’t be able to tell (when seeing our collection) how people dressed in Antwerp. Of course you can document street fashion, maybe through imagery or video, but how to document everything that appears online?

What makes something worth adding to the archive— how do you select?

There are different reasons why you select a specific designer or a specific look. There’s no handbook of how to collect. Somehow you try to maintain objective criteria to decide why a look is interesting or relevant. That can be because a look represents a designer’s signature style; maybe the object has an interesting technique; sometimes you collect with an upcoming exhibition in mind; and you also collect with an existing collection in mind. You take into account what people before you were collecting and you try to fill in the gaps.

Are designers more willing to donate their collections to the museum nowadays, as it seems that fashion exhibitions are gaining popularity in general?

Nobody knew us when we started fifteen years ago, but now designers find it important to have their pieces in the ModeMuseum. Many designers and fashion houses keep archives themselves, but do it with very different goals compared to museums. We try to keep pieces in the best possible condition for future generations, which also gives us limitations as they can’t be worn by people anymore, because textiles are very fragile. Sometimes designers take pieces out of their own archives and are inspired by it for a new collection; re-do the patterns a bit, or use it for photoshoots, but when people donate their pieces we unfortunately cannot give them back to designers for those purposes.

“IN THE 90S, YOU SEE DESIGNERS LIKE WALTER VAN BEIRENDONCK AND RAF SIMONS WORK WITH A LOT OF NEW MATERIALS LIKE LATEX AND NEOPRENE, WHICH ARE NOT EASY TO MAINTAIN. THEY DON’T DESIGN WITH THE IDEA THAT THESE MATERIALS SHOULD LAST FOR 200 YEARS OR LONGER, OF COURSE.”

Are there a lot of students who request access to your archives?

Yes, but we have very small teams and allowing access is often very difficult. If somebody wants to research a 19th century piece for the whole afternoon, it means that somebody needs to assist them during that time. We think it’s very important that there’s an access to the collection, as we don’t want a whole generation of designers and researchers to grow up without physical contact with the garments. Last year, we started a ‘Study Collection’. The idea is that people can access it very easily in the Reading Room of our library, where you don’t have to make an appointment half a year in advance. These pieces are often doubles from the collection that we have, and we also want to add contemporary designs to it. We also have sample books with specific techniques, so you can touch and look at these pieces in detail.

It’s interesting to hear how you talk about fabrics, as you can read all over the internet about how they have changed over the past couple of years — how garments, for example, are now designed to fall apart after a few years. Do you notice any differences when you look at old and new garments?

There were periods in history where they dyed fabrics with materials that now actually damage them. We have a lot of silks that were dyed in a certain way, and we’re slowly losing them, well, actually quite rapidly, and we can’t stop the process. But, for example the plastics that designers started using in the 50s and 60s are also hard to maintain, as well as the paillettes or gelatin that designers used in the 20s. Also, in the 90s, you see designers like Walter van Beirendonck and Raf Simons work with a lot of new materials like latex and neoprene, which are not easy to maintain. They don’t design with the idea that these materials should last for 200 years or longer, of course.

Is the way that you conserve things changing too? Are there any innovating techniques?

We are researching it all the time and have a big network of colleagues worldwide who are facing the same problems. We have a storage space with climate conditions that are very specific: between 18-20 degrees Celsius temperature and a humidity between 50-55%. We now think that some materials need a different kind of humidity or temperature, so we are trying to find the ideal conditions to conserve these materials. We are currently doing a project on a jacket by Martin Margiela, which is imitation leather, but the coating of the jacket comes loose, and we haven’t found a technique to restore it yet.

It sounds like a race against the clock.

It is! We’ve now got a technique of storing it oxygen-free in a plastic bag: there’s air in it, but the oxygen is pulled out. Through keeping it oxygen-free, we can stop the process, so if we find a way to restore it in a few years time, we will re-open it. It’s a complex job of finding solutions, and it often takes a number of years for just one object.

“IT’S MORE DIFFICULT TO STORE A CD-ROM OF THE 90S THAN A 18TH CENTURY COSTUME.”

I’m also curious if there is an aesthetic difference between seeing something in a boutique or in a museum?

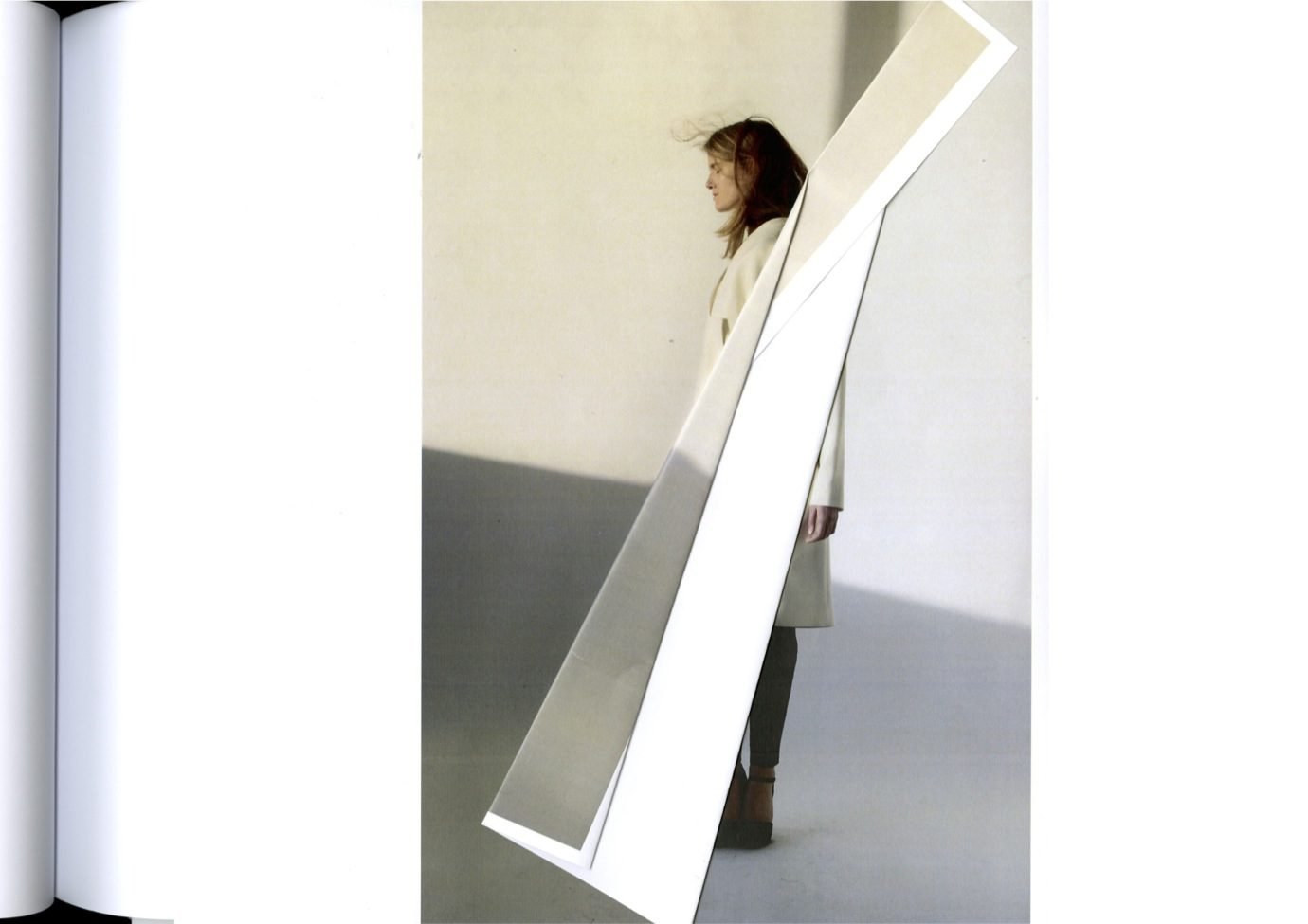

Yes, indeed. One of the biggest challenges, which I told you about, is how you see dynamics in a museum. When we make an exhibition, the first thing we ask ourselves is: which mannequins do we use to display the garments? We look for a neutral body, but what you usually find in the market are mannequins in very sexy poses, with big breasts, or men with puffed chests. It’s problematic. It’s very different if you would instal Dries van Noten or Ann Demeulemeester pieces on a mannequin that has a body like that. You always have to think about what kind of female or male body the designer had in mind. I think that creating fashion is also about translating a body; and each designer does it in a different way. As a museum you have to be conscious about that and find a replacement for that body. It’s an important decision, because if you pick the wrong body, it will look really weird or wrong.

How do you see museums and curating practise change in the next 15-20 years?

The digital world is absolutely crucial; we have digital walls in the entrance of the museum, which we launched in February. What we have is a digital touchscreen where up to 15 people can simultaneously find information about the museum, the Fashion Department and the Flanders Fashion Institute, and also discover our collections through images. So, you can touch an image of Ann Demeulemeester, and each image is tagged with a number of words: ‘white’, ‘embroidery’, ‘leather’ — and when you touch ‘leather’, you can find different creations constructed of, or featuring leather in our collection.

We want to develop that technology further, and increase engagement by making it more interactive. I would really love it if people could download images with their smartphones and really have an interaction with the wall. We not only have a collection of 30.000 objects, garments, accessories and textiles, but we also have a collection of more than 500.000 digital object. The digital collection is actually much more fragile than the historical collection. Many designers come to us with their collections stored on CD-ROMs, but even specialist teams can’t open them anymore. It’s more difficult to store a CD-ROM of the 90s than a 18th century costume. Maintaining or storing collections is one thing, but giving the audience access to these digital images is another challenge, as we have so many images in our archive to which we don’t own the copyright. We’re working with a number of photographers and designers in order to give people access, but the other question is: how can we curate that material? That’s obviously a big question moving forward.”

… And an area that will no doubt see the biggest change. Let us know your thoughts below the line, or @1Granary via Twitter.