The static element of prosthetics “came from the idea of our cultural vision towards care, compared to that of the Ainu. For them, tattooing around the mouth and arms is believed to (amongst other things) protect them from diseases. It is something that they show with pride, to such an extent that they even reproduce the motives on the edges of their kimonos. In our culture, we try to hide it as much as possible when we need the help of a garment or object to feel better, like bandages, medical corsets, or braces. It has this connotation that you’re weak, when it’s just a normal thing to do. So I wanted to show that in itself, a medical garment doesn’t have to be hidden, there is also some kind of beauty in it, when you abstract it from the context.”

Antwerp Fashion Department graduate Sofie Gaudaen finds adornment in the functional

The final collection of Royal Academy of Arts Fashion department graduate Sofie Gaudaen – “Ainu Stroke”, intended for empowering its wearer – is a small scale disturbance to channel, yet not to be overdone. It features prosthetics of the softest colors. One might believe the nature of garments is the function of protection, however, Sofie’s fashion “seems to me more about exposure, about taking risks.”

“INSANITY WOULD BE MORE INTERESTING.”

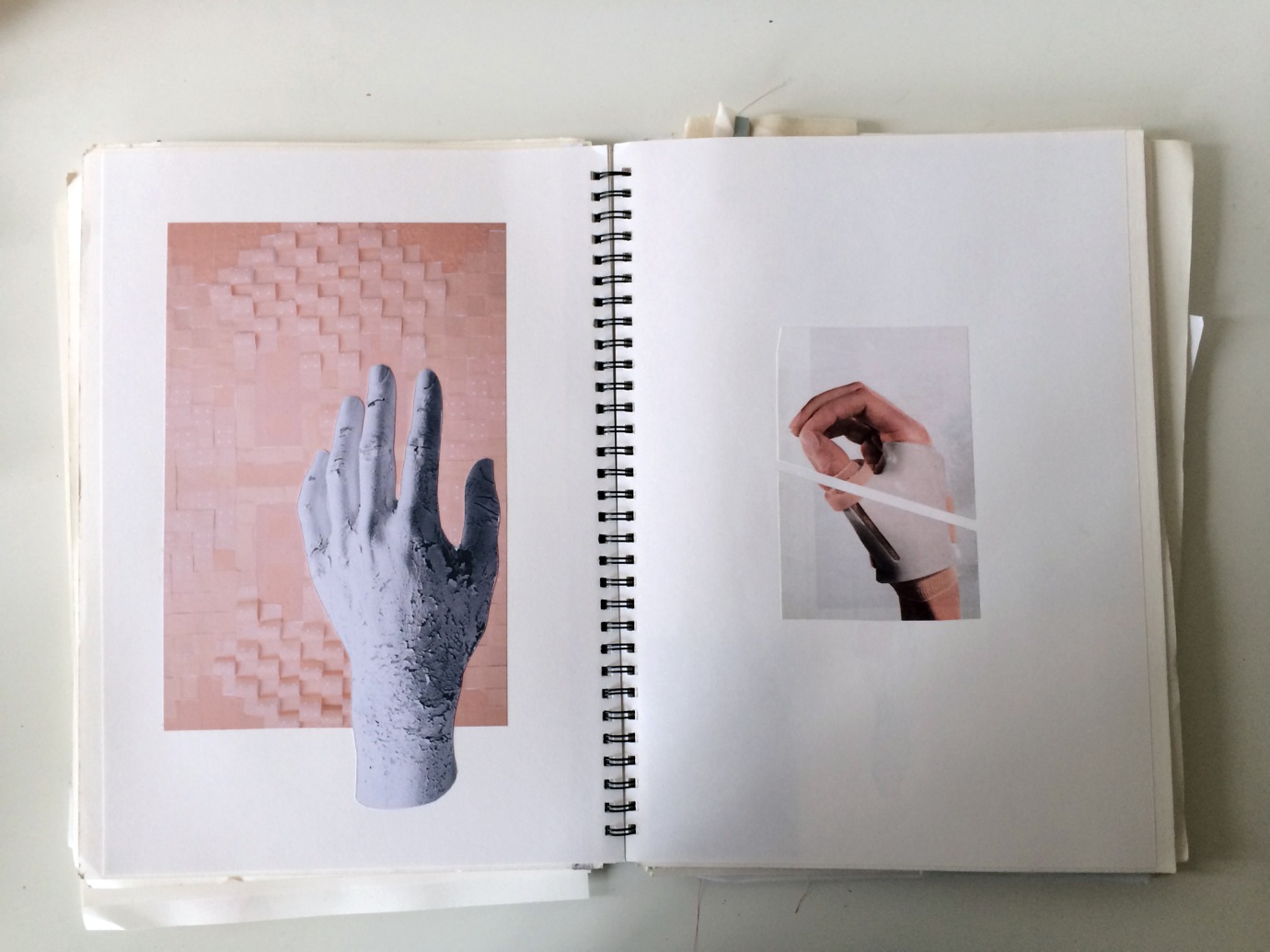

This dystopic beauty was combined with a collection of experimental textiles of soft touch. “In that way, it made sense to me to mix those medical elements (or at least what I found interesting in them – the texture, the fabrics, the embossed parts, the closings) with softer or more classical fabrics, to enhance the contrast between medical/technical versus traditional.”

The textiles come in pastel colours to evoke sanity: “they’re the colors that you find back in hospitals, or in materials that are used for medical purposes. Probably because they’re not aggressive on the eye, they keep you calm.” Or should it rather be described as a discussion of insanity: “Insanity would be more interesting.”

These textiles are a collaboration with Anita Evenepoel. The pairing was born within the university, when Anita held a masterclass for students called “Serendipity versus Craft” in her atelier. “She has plenty of interesting machines and materials that we could play with, and an extensive knowledge about materials, especially synthetics. I think by the end of the workshop she reconciled most of the fashion students with the ‘big bad world’ of synthetic materials.” After this event, Sofie went to Anita asking if she could show her how to emboss fabric with a pattern. “She told me it necessitated machines that we didn’t have on hand by then, so I tried different ways to get close to it. It ended up being a lot more manual than I thought. I spent hours cutting and placing little pieces of spacer between two layers of mesh before fusing them with a heat press, but the result was close to what I wanted.”

“IN OUR CULTURE, WE TRY TO HIDE IT AS MUCH AS POSSIBLE WHEN WE NEED THE HELP OF A GARMENT OR OBJECT TO FEEL BETTER, LIKE BANDAGES, MEDICAL CORSETS, OR BRACES. IT HAS THIS CONNOTATION THAT YOU’RE WEAK, WHEN IT’S JUST A NORMAL THING TO DO.”

The collection is also an integration of Japonism in a western world. Upon the question of this being an appropriation or a merge of cultures to create a new language she answers: “For me it was about the translation of an idea from one culture to another, rather than creating a new language. I liked the idea of care in the Ainu culture; this duality between function and aesthetic in the tattoos and motifs on the kimonos. I wanted to see if it would work in our culture, to consider something functional as adornment.”

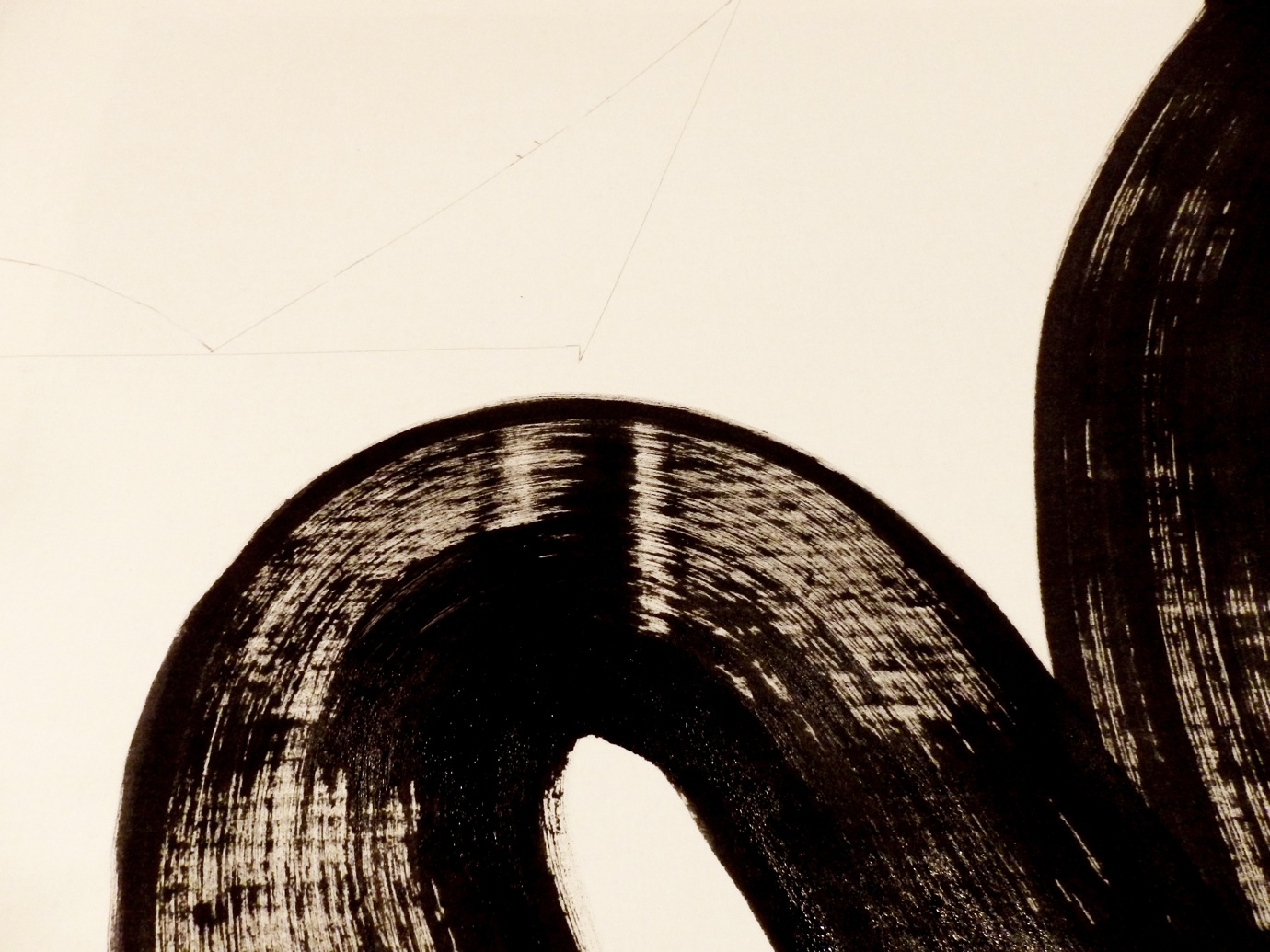

The brush strokes inspired by the Ainu tattoos seem spontaneous in contradiction to the prosthetics. ”For me it made sense. I didn’t want the tattoo idea to be too literal, and I liked the idea that the braided shapes from the tattoos were reproduced on the kimonos, so I decided to put the pigment directly on the garment. I looked a lot at abstract expressionist paintings last summer, especially the work from Pierre Soulages, so I wanted to do something with it. One part of his work consists of big brushstrokes, like abstracted calligraphy, using different kinds of mediums (from lithography to walnut stains). Instead, I decided to use one single kind of paint on different fabrics, to achieve different textures. The result is a blown up, abstracted version of the tattoos, and I think it contrasted well with the stiffness of the medical-inspired pieces.”

Sofie’s state of mind is moving. She thinks the more people are able to move in a garment, the more elegant they look; hence the sense of movement in contradiction to the prosthetics in her work. However, she believes “there’s no should or should not in fashion. Some people make great sculpture-garments, others make beautiful corsets. It’s just not my thing.”