What have you been up to before you decided to move to Antwerp and study at the Fashion Department?

Before I started to study at the Academy in Antwerp, I lived in Berlin for a couple of years. I moved there after finishing high school, due to German small town depression. I studied Performance Studies and Art History at the Freie Universität Berlin before I started an internship in the bespoke tailoring department of the Stiftung Oper Berlin, which unites the costume departments of Berlin’s opera houses, the ballet and some theaters. While studying at the Academy, I interned with Hilde Frunt: an Antwerp-based knitting goddess. Currently I am working on my master’s collection, in my fourth year at the Antwerp Academy.

What are the main reasons why you are attracted to the contrast between classic menswear and savage men’s culture?

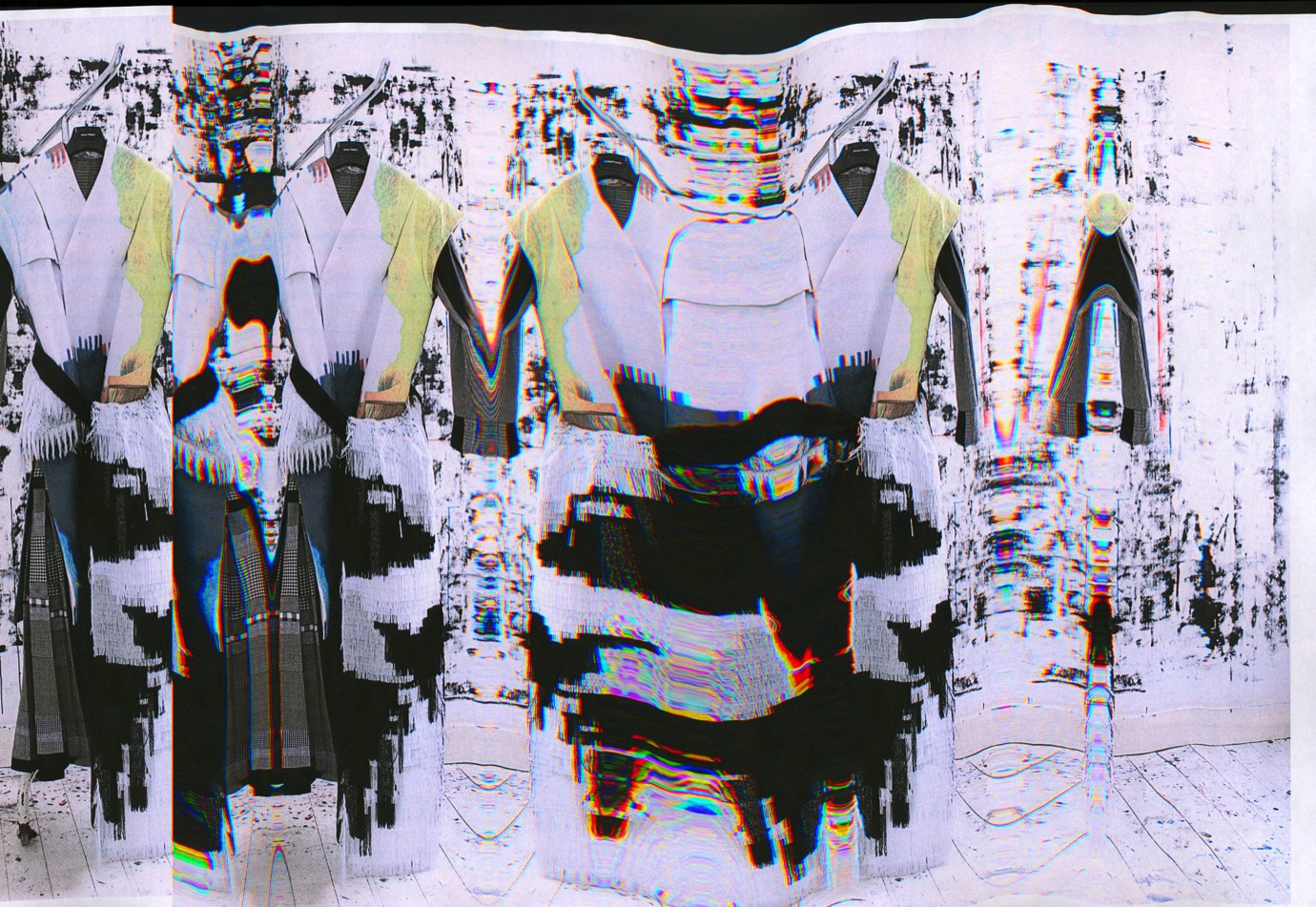

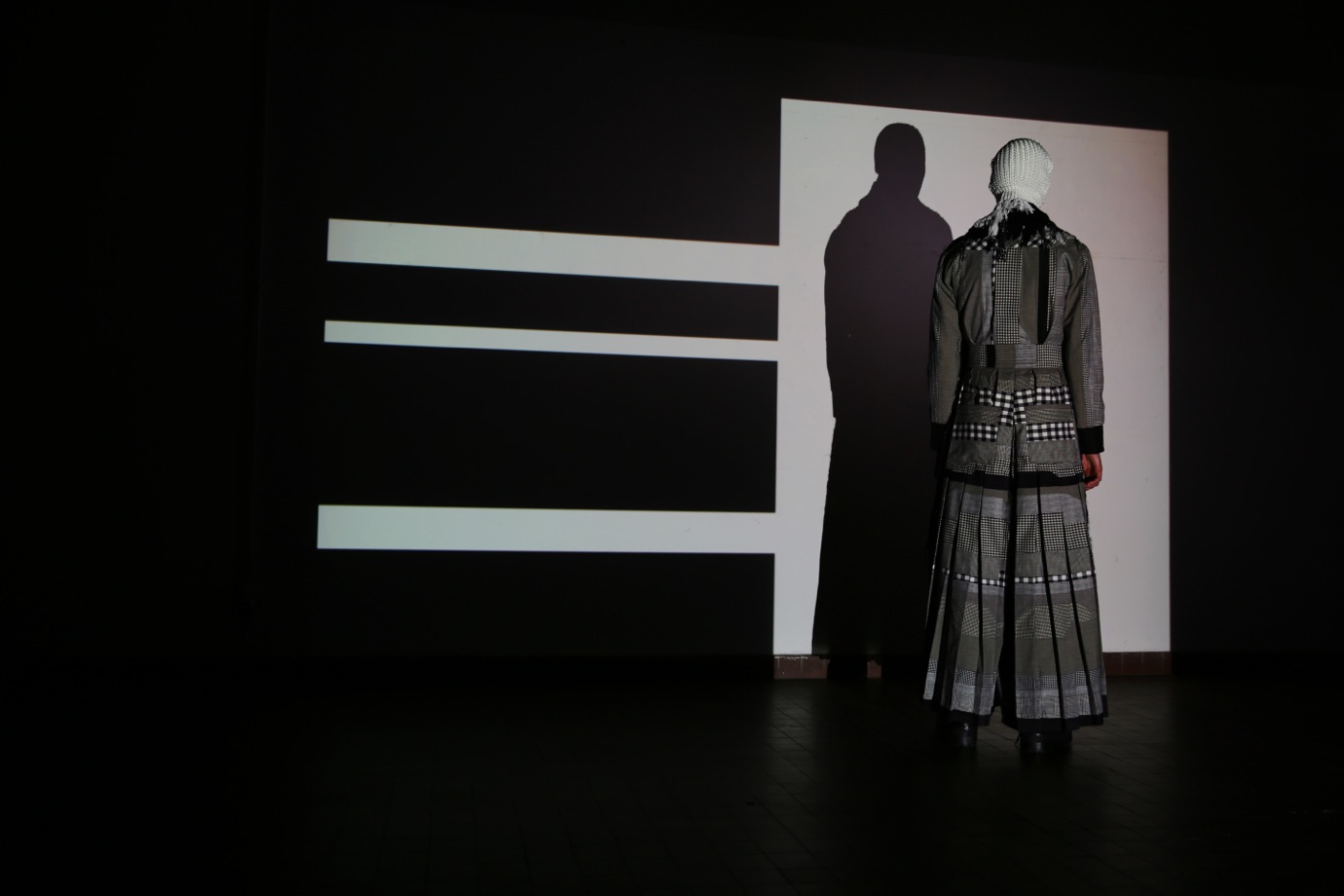

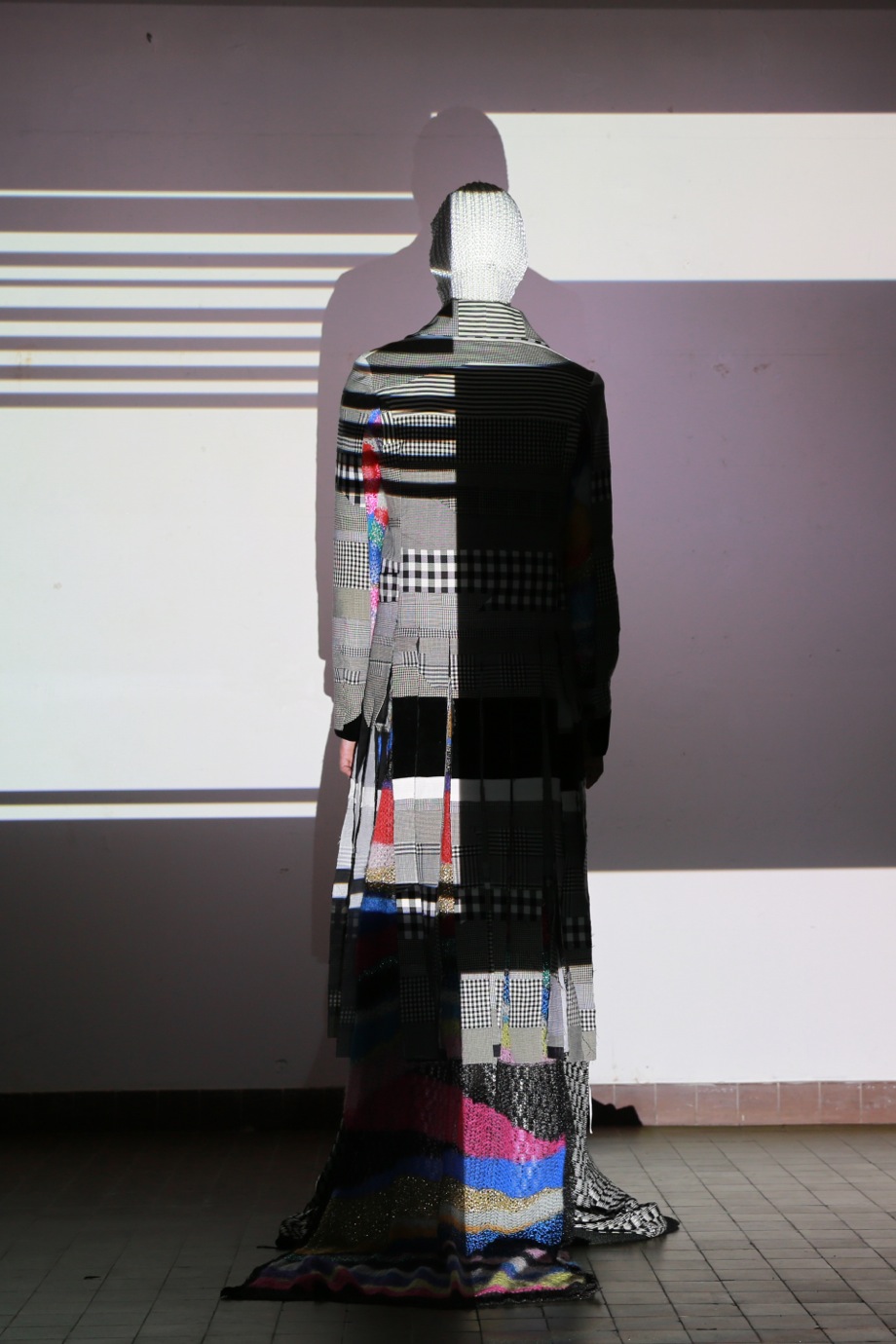

Approaching my work with the intention to make a men’s collection last year, made me wonder what it is that defines the ‘masculine’. I started to think about male-dominated culture; extreme examples for that were the catholic clergy and the military. All of these systems operate with very rigid rules and severity, and at the same time emerge in a great deal of violent or ‘savage’ behavior. It can take many different forms; if you go to a big gay club in Berlin, it is equally apparent. So I tried to transfer this quality into my collection. The codes of classic menswear and the vestments of priests provided a very ridged rulebook that was there to be ‘violated’.

Besides Larry Clark and Wolfgang Tillmans, who or what influences your work?

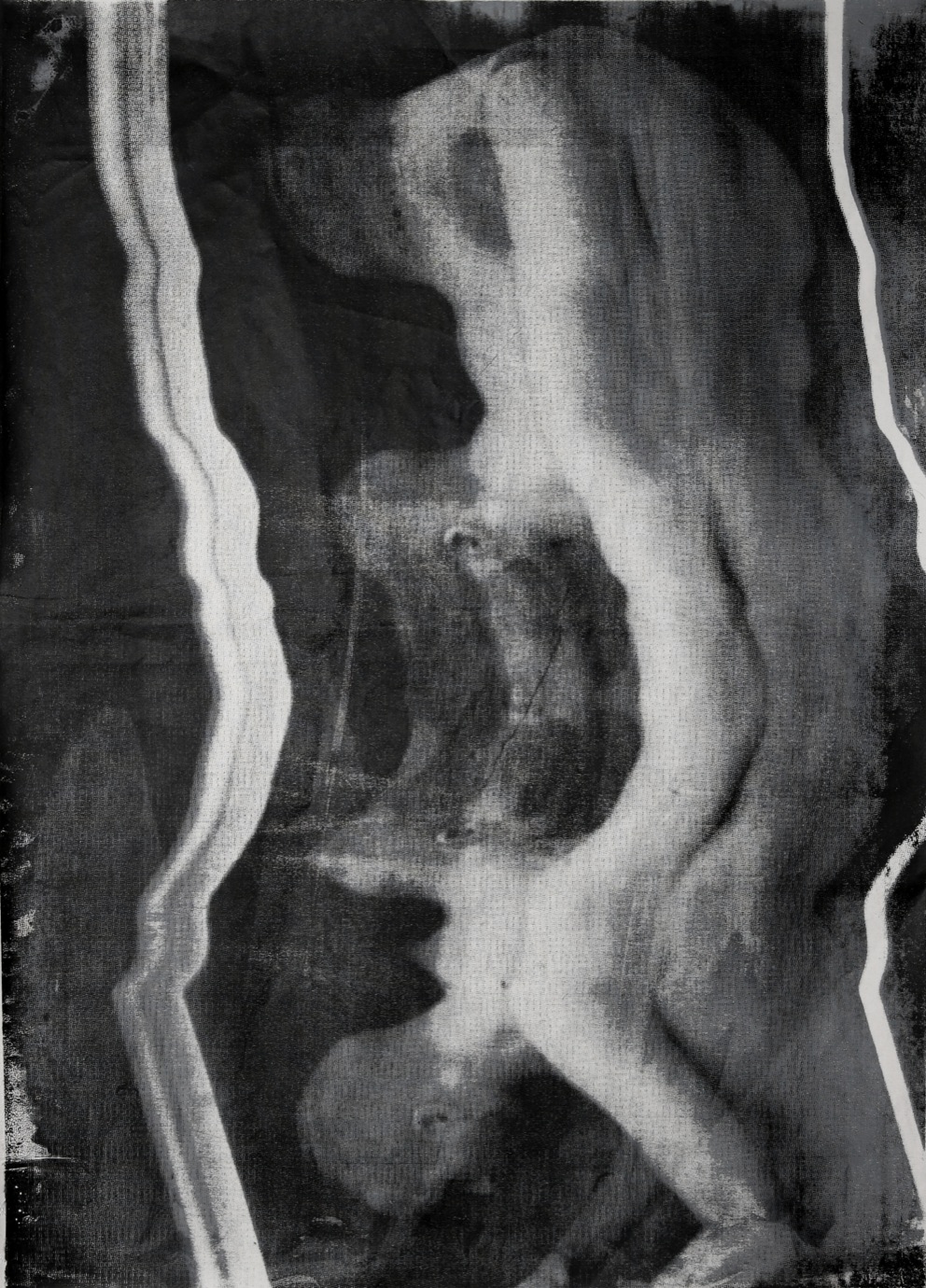

What interested me about Tillmans and Larry Clark especially, is the sort of roughness and honesty with which sexuality and physicality are represented. There is very little ‘allure’ to the whole thing, very little ‘sexiness’, which I find to be a bit of a misanthropic concept in itself.

To answer the question of what besides these specific artists influences me is sort of difficult, and the answer will be a bit cliché: it seems to be a common understanding that fashion is a mirror of its time, and that might apply to any artistic medium. It is about making context and bringing things together. The ‘bigger picture’ discussions with friends are equally as important as watching the news, movies, television, reading books, visiting exhibitions, taking a walk in the streets. It’s about understanding notions, making connections and finding a form for them.