“ENOUGH WORK MUST BE COMPLETED BEFORE IT BECOMES COMPLETELY SELF-REFERENTIAL AND FAR FROM COMMON INTERPRETATIONS.”

Where did your primary inspiration come from?

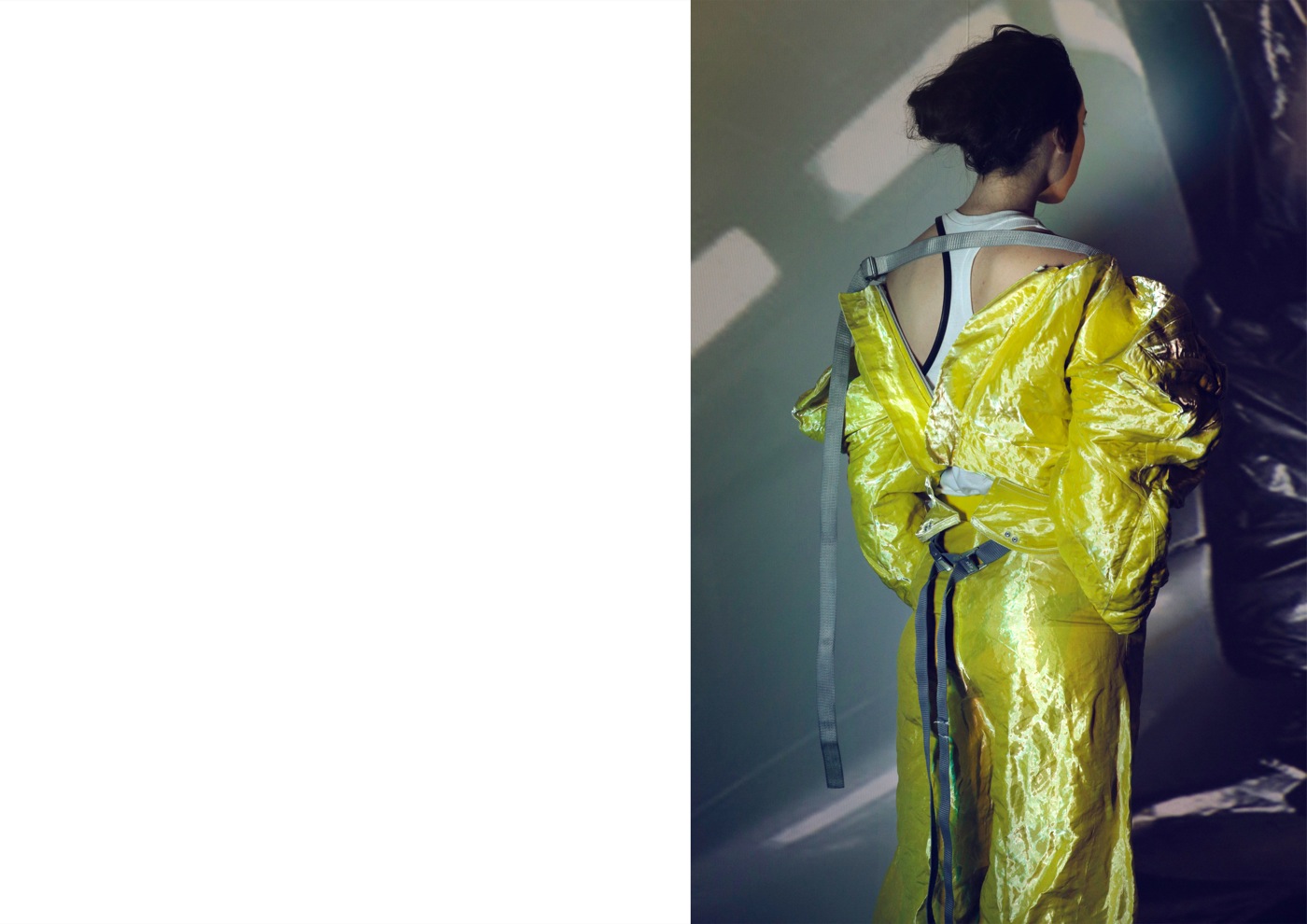

Most of my initial inspiration comes from film and TV watching, and super bored idling as a kid. I was into manga, comic books and BMXing. Also, my parents raised me with their unique aesthetic in a recreation of a 30s/50s home. Being surrounded by objects with a strong aesthetic identity gave more fantasy and appreciation of escaping the visual mundaneness of the everyday, and being surrounded by fabulous items of a forgotten generation. Altogether, these were moments for opting out of reality and it is a feeling that I try to capture through my work — is this deep enough for me to get lost in? Do I believe in this altered reality? Is it credible? If so, I hope it takes others in with it.

Can you tell a bit more about your research process?

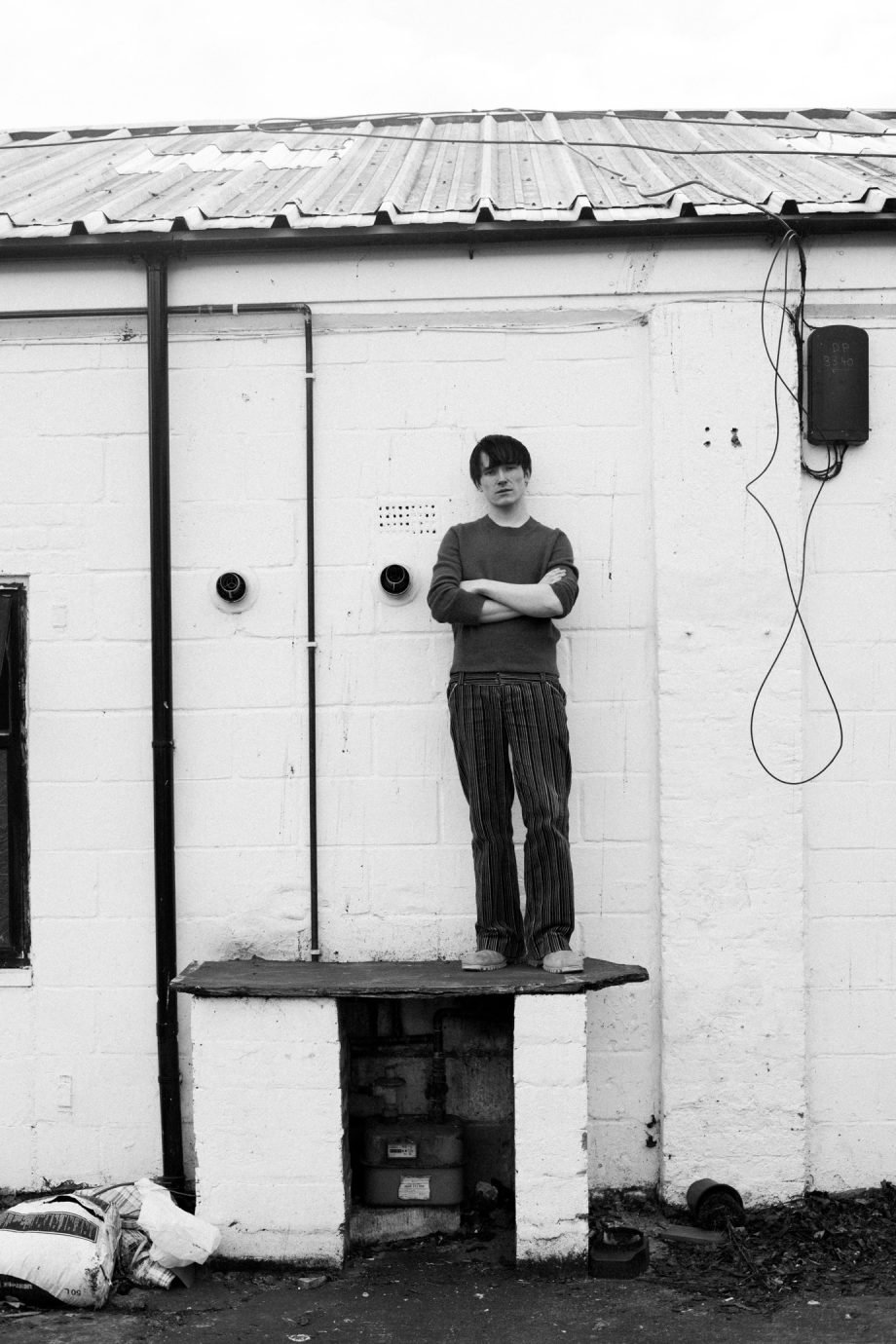

Primary research is great: it starts the project, it grounds out an idea, and it gives clear referential backing. However, I quickly move on to the concept in which bolder work can be carved out by seeking other ways of channeling ideas. It taught me to work and rework ideas repeatedly, into a place where I could edit concepts from the imagery I was creating. It was an exercise to give more dimensions to understanding what it was that I was making. Forming a vast network of trial and error is necessary, so that it starts informing and shaping each other. Enough work must be completed before it becomes completely self-referential and far from common interpretations.

Can you speak about the significance of experimentation and development?

It’s crucial, as there is so much failure in it. Failure gives its own rewards, although it may be difficult to see. It informs a great deal and it stops you from predicting how things might look or work, because it rarely turns out the way you expect it to. I had to go through endless attempts before resolving techniques, and putting practices into a place I did not think would ever be possible. Despite these failures, I persevered until I felt I had resolved the problem.